Scottish Bathing Waters Report 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of Walking in Scotland

1 The Best of Walking in Scotland Scotland is a land of contrasts—an ancient country with a modern outlook, where well-loved traditions mingle with the latest technology. Here you can tread on some of the oldest rocks in the world and wander among standing stones and chambered cairns erected 5,000 years ago. However, that little cottage you pass may have a high-speed Internet connection and be home to a jewelry designer or an architect of eco-friendly houses. Certainly, you’ll encounter all the shortbread and tartan you expect, though kilts are normally reserved for weddings and football matches. But far more traditional, although less obviously so, is the warm welcome you’ll receive from the locals. The farther you go from the big cities, the more time people have to talk—you’ll find they have a genuine interest in where you come from and what you do. Scotland’s greatest asset is its clean, green landscapes, where walkers can fill their lungs with pure, fresh air. It may only be a wee (small) country, but it has a variety of walks to rival anywhere in the world. As well as the splendid mountain hikes to be found in the Highlands, there’s an equal extent of Lowland terrain with gentle riverside walks and woodland strolls. The indented coastline and numerous islands mean that there are thousands of miles of shore to explore, while the many low hills offer exquisite views over the countryside. There’s walking to suit all ages and tastes. Some glorious countryside with rolling farmland, lush woods, and grassy hills can be reached within an hour’s drive of Edinburgh and Glasgow. -

A6359 Findynate Estate

44 A RCHERFIELD DIRLETON , N ORTH BERWICK 44 A RCHERFIELD DIRLETON, NORTH BERWICK, EH39 5HT DIRLETON 2.5 MILES, GULLANE 2.9 MILES, NORTH BERWICK 4.5 MILES, EDINBURGH 24 MILES, EDINBURGH AIRPORT 32 MILES Magnificent conteMporary Mansion house with far reaching views to the firth of forth, set in extensive landscaped gardens within the prestigious archerfield estate Vestibule, Reception Hall, Drawing Room, Dining Room, Study, Cloakroom, WC, Open Plan Family Kitchen with Dining and Seating Areas, Family Room Master Suite with Dressing Room and En Suite, 4 Further En Suite Bedrooms Attic Playroom/Cinema Self-Contained Apartment with Two Bedrooms, Bathroom, Open Plan Kitchen, Dining and Sitting Room Four Car Garage. Laundry Room. Gardener’s WC Landscaped Gardens and Woodland EPC Rating = C About 4 acres in all situation 44 Archerfield is set in four acres of land within the historic Archerfield Estate. The house sits on the largest plot on the development and is set slightly apart from the remaining development, flanking the 14th fairway of the Fidra Links golf course, giving uninterrupted views over Yellowcraigs beach and Fidra island, with Fife and the Isle of May on the horizon. The Village is a fully established modern development in the beautiful coastal countryside of East Lothian, between Gullane and Dirleton. Lying just east of the famous Muirfield Links, home to the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers, and nearby Gullane, Luffness and North Berwick golf courses, the Estate has its own rich golfing history, with the first game taking place here in 1868, and an 18 hole course created in 1910. -

Aberlady Aberlady, East Lothian, EH32 0RX Viewing by Appt Tel Client 07985 404289 Or Agent

Rowen & Willow Cottage, Haddington Road, Fixed Price £575,000 Aberlady Aberlady, East Lothian, EH32 0RX Viewing by appt tel Client 07985 404289 or Agent 01620 892000 | eastlothianprimeproperty.com Description Rowen and Willow Cottage offer a rare opportunity to purchase a unique and individual detached house with a separate annexe cottage situated within a popular village location with outstanding views over the East Lothian countryside. The main house is well presented throughout and the addition of the cottage annex offers a variety of options depending on the purchaser’s needs. The current owner runs a successful holiday rental business (www.willowcottageaberlady.co.uk). This flexible space could also be used for family members or incorporated into the main property to create one large house. The main house currently has four bedrooms and the cottage has two bedrooms. There are charming south facing mature gardens and off street parking which add to the appeal. Local amenities are available within easy walking distance of the house. The flexible and spacious accommodation is arranged over two floors and comprises in the main house: Ground floor - welcoming entrance hall with cupboard and lockable door to the annexe; kitchen/dining room to the front fitted with an excellent selection of painted units with ample room for a large dining table; the bright living room has 3 large picture windows overlooking the gardens and a fireplace providing an attractive focal point; the conservatory provides another flexible living space with direct access to the garden; double bedroom 3 and double bedroom 4 and bathroom with white suite; and on the first floor - master bedroom with large wardrobes; double bedroom 2 and bathroom with white suite. -

“3 Wishes” for the North Berwick Coastal Area - a Report of Your Responses

Your “3 Wishes” for the North Berwick Coastal Area - a report of your responses This report details the responses received from the “3 wishes” exercise carried out by the North Berwick Coastal Area Partnership who wanted to find out directly from local people and groups what they wanted to make their communities better places to live. The Area Partnership members wanted to give people an opportunity to participate and influence the Area Plan which will detail all of the actions that need to happen to make the area an even better place to live, visit, and get around. The exercise was carried out from July to September 2015 and the form was available in either paper format or online. Area Partnership members also spoke directly to some local people and groups who may not have participated otherwise, such as residents in local care homes. The Respondents Over 56 people and groups completed the questionnaire (42 via survey monkey and 14 on paper). Not all of the people and groups left their name but those that did were: The Beach Wheelchair Project Dirleton Village Association The Arts Centre Group Law TRA 6 year pupils at North Berwick Lime Grove TRA High NB Youth Network Local Care Homes and Older Older Peoples Working Group people North Berwick Youth Project North Berwick Day Centre Aberlady Village members Drem Parents Gullane Area Community Council The Abbey Care Home (GACC) Dementia Friendly North Berwick What we wish for our children to lead happy, healthy lives We wish for more opportunities for children to play both indoors and out by developing more soft play type activities and using models such as “the Play Ranger” that use challenging and risky play opportunities in safe environments. -

John Muir Coast to Coast Trail: Economic Benefit Study

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 508 John Muir coast to coast trail: Economic benefit study COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 508 John Muir coast to coast trail: Economic benefit study For further information on this report please contact: Rob Garner Scottish Natural Heritage 231 Corstorphine Road EDINBURGH EH12 7AT E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: The Glamis Consultancy Ltd and Campbell Macrae Associates (2012). John Muir coast to coast trail: Economic benefits study. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No.508. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the authors of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2012. i COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary John Muir coast to coast trail: Economic benefit study Commissioned Report No. 508 Contractor: The Glamis Consultancy Ltd. with Campbell Macrae Associates Year of publication: 2012 Background This study sets out an estimate of the potential economic impact of the proposed John Muir Coast to Coast (JMC2C) Long Distance Route (LDR) across Central Scotland. This report provides an assessment of the overall economic impact that could accrue from the development of the JMC2C route, as well as disaggregating this down to the individual local authority areas which comprise the route. It also recommends ways of maximising the economic impact of the route through targeting its key user markets. Main findings: Estimated impact of the JMC2C proposal - It is estimated there will be 9,309 potential coast to coast users in the first year of the JMC2C potentially generating £2.9m of direct expenditure and creating or safeguarding 127 FTE jobs in year one. -

Scottish Day Tours on Board Executive Lothian Motorcoaches Vehicles

EXPLORE FURTHER WITH TOUR HIGHLIGHTS TOP TOUR TIPS SCOTTISH You can hop on and hop off our tours all day, giving you 30 JUNE - 30 SEPTEMBER 2018 plenty of time to explore the places you choose to visit. Our best value Explorer ticket also includes unlimited travel DAY TOURS on East Coast Buses, so you can see even more of East Lothian. EXPLORE EAST LOTHIAN Hop off at stop 5 and take a short walk to catch East Coast Buses X7. Visit sights such as Foxlake Adventures, Belhaven BY OPEN-TOP BUS Brewery and East Links Family Park. Travel on service X7 is included with an Explorer ticket. EASY ACCESS TANTALLON CASTLE DIRLETON CASTLE Great savings with your tour ticket! Enjoy fantastic discounts Hop off at stop 3 to explore Tantallon Castle, a semi-ruined Hop off at stop 1 0 to visit Dirleton Castle, a magnificent at the National Museum of Flight, NB Gin Distillery and the 14th century fortress set on the cliff edge with stunning fortress–residence with impressive grounds. Look out for the Scottish Seabird Centre. views over the Firth of Forth to Bass Rock. dovecot - one of Scotland’s best-preserved pigeon houses. You can’t beat local knowledge! Our live guides really know their stuff - if you have any questions just ask, they’ll be happy to help! Explore even more of Scotland. See the best of the capital with five-star open-top Edinburgh Bus Tours and marvel at Scotland’s stunning landscape and attractions with Scottish Day Tours on board executive Lothian Motorcoaches vehicles. -

North Berwick Coastal Ward Area Partnership

North Berwick Coastal Ward Area Partnership Top 12 priorities from 3 wishes exercise Great place to ****************** live – children Bursary scheme for children/families *** and young Link this with action: (21 inc 12 yellow people Activity budget for young people stars) Great place to - Refurbish youth project ****************** live – children - Re-decorate the youth project – paint, new lights, new chairs, serving area with Coffee * and young machine and facilities for light snacks (19 inc 13 blue stars) people - Proper advertising, signage for outside the building of youth project Great place to Support for Dementia Friendly North Berwick Activities ****************** live – older (18 stars) people Get Around Paths. Developing a core path network to provide accessibility for all and linking communities in a ********** sustainable way. Specifically, this includes better access at yellowcraigs, Gullane, glen and the Law, **** (14 stars) Drem (to access transport) and Dirleton and cycle routes. Great place to Beach cleaning/grooming ************ visit - The Notes: (12 stars) beaches and East/West bay (Environmental cycle) harbour Gullane - Lifeboat slip way) – where does it go? Great place to Laptops, I pads for use in care homes and day centre. This helps for people to keep in touch with *********** (11 live – older friends and family stars) people Notes: - ensure the equipment is drop proof, look for match funding from sources such as Sally Magnusson, age UK, IJT. - University of Age – could run local session and link with Great place -

Public Toilet Statistics

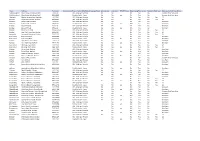

Area Address Postcode Co-ordinates Type of toilet (WC, Baby Changing, AccessLevel access attended - YRADAR Key reqBaby ChangiFree to use Payment Re24 hour Opening hours (if not 24 hour) Athelstaneford Main Street, Athelstaneford EH39 5BE WC - Male and Female No No No Yes No Summer Only 9am-6pm Athelstaneford Main Street, Athelstaneford EH39 5BE Disabled toilet - basic Yes No yes No Yes No Summer Only 9am-6pm Aberlady Nature Reserve Bay, Aberlady EH32 0PY WC - Male and Female Yes No No Yes No Yes 24 Direlton Village Main Street, Dirleton EH39 5ET WC - Male and Female Yes No No Yes No Yes 24 Direlton Yellowcraigs, Dirleton EH39 5DS WC - Male and Female Yes No Yes Yes No 9am-6pm Dirleton Yellowcraigs, Dirleton EH39 5DS Disabled toilet - basic Yes No yes N/A Yes No 9am-6pm Dunbar Bayswell Road EH42 1JJ WC - Male and Female Yes Yes Yes Yes No 9am-6pm Dunbar Bayswell Road EH42 1JJ Disabled toilet - basic Yes Yes yes N/A Yes No 9am-6pm Dunbar Bilsdean A1 Road None known WC - Male and Female No No No Yes No Yes 24 Dunbar Deer Park Cemetery, Dunbar EH42 1QJ WC - Male and Female No No No Yes No Yes 24 Innerwick Innerwick Cemetery, Dunbar EH42 1SA WC - Male and Female Yes No No Yes No Yes 24 East Linton East Linton Park EH40 3AH WC - Male and Female Yes No No Yes No 9am-6pm East Linton East Linton Park EH40 3AH Disabled toilet - basic Yes No No No Yes No 9am-6pm Dunbar John Muir Country Park EH42 1TU WC - Male and Female Yes No Yes Yes No 9am-6pm Dunbar John Muir Country Park EH42 1TU Disabled toilet - basic Yes No yes N/A Yes No 9am-6pm East Linton -

Your “3 Wishes” for the North Berwick Coastal Area - a Report of Your Responses

Your “3 Wishes” for the North Berwick Coastal Area - a report of your responses This report details the responses received from the “3 wishes” exercise carried out by the North Berwick Coastal Area Partnership who wanted to find out directly from local people and groups what they wanted to make their communities better places to live. The Area Partnership members wanted to give people an opportunity to participate and influence the Area Plan which will detail all of the actions that need to happen to make the area an even better place to live, visit, and get around. The exercise was carried out from July to September 2015 and the form was available in either paper format or online. Area Partnership members also spoke directly to some local people and groups who may not have participated otherwise, such as residents in local care homes. The Respondents Over 56 people and groups completed the questionnaire (42 via survey monkey and 14 on paper). Not all of the people and groups left their name but those that did were: The Beach Wheelchair Project Dirleton Village Association The Arts Centre Group Law TRA 6 year pupils at North Berwick Lime Grove TRA High NB Youth Network Local Care Homes and Older Older Peoples Working Group people North Berwick Youth Project North Berwick Day Centre Aberlady Village members Drem Parents Gullane Area Community Council The Abbey Care Home (GACC) Dementia Friendly North Berwick What we wish for our children to lead happy, healthy lives We wish for more opportunities for children to play both indoors and out by developing more soft play type activities and using models such as “the Play Ranger” that use challenging and risky play opportunities in safe environments. -

Offers Over £495,000 Aberlady 2 Garleton Park, Aberlady, East Lothian, EH32 0UH Viewing by Appt Tel Agents 01620 892000

Offers Over £495,000 Aberlady 2 Garleton Park, Aberlady, East Lothian, EH32 0UH Viewing by appt tel Agents 01620 892000 01620 892000 | eastlothianprimeproperty.com Description Stunning five bedroom detached family home by CALA with generous living accommodation, private rear garden and double garage. The property is in a quiet cul-de-sac and within easy reach of the primary school and village centre. The flexible accommodation, on two floors, comprises on the ground floor - vestibule; spacious entrance hall with understairs cupboards and WC off; living room with bay window to the front and fireplace with gas fire; double doors lead to the family room/dining room which has a window to the rear; open plan kitchen/dining room/family room with French doors and window overlooking the rear garden, excellent selection of cream units with matching work surfaces, integrated appliances, breakfast bar, space for a large dining table and family area with window to the front and utility room with clothes pulley, window to the side, door to the rear and door to the double garage; and on the first floor - bright and spacious landing with two cupboards and hatch to partially floored loft, master bedroom with bay window to the front, dressing room and en-suite bathroom with bath, large shower enclosure, WHB, WC and bidet; double bedroom 2 to the front with built in wardrobe and en-suite shower room, double bedroom 3 to the rear with built in wardrobes; double bedroom 4 to the front again with built in wardrobes, double bedroom 5 again to the rear with shelved cupboard and family bathroom with bath, separate shower enclosure, WHB and WC. -

Welcome to the Final Edition of Our School Newsletter for This Session

Welcome to the final edition of our school newsletter for this session. We have dispensed with the two column format for our newsletter, as an across-the page structure is much easier to read online. Thanks to those parents who fed that information back to us. End of Year Reports I should like to begin this newsletter by taking time to comment on the quality of the pupil reports. As you would expect, I have read all of these and I am very impressed by both the detail that class teachers have been able to convey and also the confirmation that they know all of their pupils so well. I must commend the industry and keen perception of all the teaching staff in this regard and would also wish to thank the support staff for compiling the final format of the report. It is so pleasing to read about hard-working, well-motivated and enthusiastic pupils! I am sure that you will agree with me on that, too! Student Placement – Miss A O’Rourke We have enjoyed having Miss O’Rourke attached to Primary 6 for her final placement this term. Thanks to the pupils and staff who made her feel so welcome. We wish her well as she moves into her probationary year. P6 & P7 Summer Performance A very lively and entertaining performance of “The Keymaster” will take place on the evening of Wednesday 24 th June in Aberlady Community Hall at 6pm. Tickets (£2 for adults & £1 for children) are available from School Office. The pupils have taken full responsibility for this – in terms of costumes, scenery, promotion, ticket design etc – and special thanks are due to them (and their teachers) for the way in which this has been so well orchestrated. -

Scottish Birds Volume 5

THE JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' CLUB Volume 5 No. 6 SUMMER 1969 Price 5s SCOTTISH BIRD REPORT 1968 earl ZeissofW.Germany presents the revolutionary10x40B Dialyt The first slim-line 10 x 40B binoculars, with the special Zeiss eyepieces giving the same field of view for spectacle wearers and the naked eye alike. Keep the eyecups flat for spectacles or sun glasses. Snap them up for the naked eye. Brilliant Zeiss optics, no external moving parts-a veritable jewel of a binocular. Just arrived from Germany There is now also a new, much shorter S x 30B Dialyt, height only 4. 1/Sth". See this miniature marvel at your dealer today. Latest Zeiss binocular catalogue and the name of your nearest stockist from: Degenhardt & Co. Ltd., Carl Zeiss House, 31 /36 Foley Street, London W1P 8AP. 01-6368050 (15Iines) _ I~~I IJ)egenhardt SCOTTISH BIRDS TIlE JOURNAL OF TIlE SOOTI1SH ORNITIlOLOGISTS' CLUB 21 Regent Terrace, Edinburgh, EH7 5BT Contents of Volume 5, Number 6, Summer 1969 Page Editorial 301 Scottish Bird Report 1968. By A. T. Macmillan (plates 20-23) 302 Review. History of the Birds of the cape Verde Islands. By D. A. & W. M. Bannerman. Reviewed by A. D. Watson 357 Request for Information 359 The Scottish Ornithologists' Club 360 Edited by A. T. Macmillan, 12 Abinger Gardens, Edinburgh, EH12 6DE Assisted by D. G. Andrew and M. J. Everett Business Editor Major A. D. Peirse-Duncombe, Scottish Ornithologists' Club, 21 Regent Terrace, Edinburgh, EH7 5BT (tel. 031-556 6042) R.S.P.B. SCOTTISH OFFICE - VACANCY ASSISTANT required for all fields of the Society's activities at the Scottish Office, Edinburgh.