Comprehensive Strategy for Serious, Violent, and Chronic Offenders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from Tobacco Industry Efforts During the 1980S to Open Closed Cigarette Markets in Thailand

Practice BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004288 on 26 January 2021. Downloaded from How to combat efforts to overturn bans on electronic nicotine delivery systems: lessons from tobacco industry efforts during the 1980s to open closed cigarette markets in Thailand 1,2 1 Roengrudee Patanavanich , Stanton A Glantz To cite: Patanavanich R, ABSTRACT Summary box Glantz SA. How to combat Until 1990, it was illegal for transnational tobacco efforts to overturn bans on companies (TTCs) to sell cigarettes in Thailand. We ► Since 2017, Philip Morris International has worked electronic nicotine delivery reviewed and analysed internal tobacco industry systems: lessons from in parallel with a pro- e- cigarette group in efforts to documents relevant to the Thai market during the 1980s. tobacco industry efforts force the Thai market to open to electronic nicotine TTCs’ attempts to access the Thai cigarette market during during the 1980s to open delivery systems (ENDS). the 1980s concentrated on political lobbying, advertising closed cigarette markets in ► As of January 2021, ENDS were still illegal in and promotion of the foreign brands that were illegal to sell Thailand. BMJ Global Health Thailand. 2021;6:e004288. doi:10.1136/ in Thailand at the time. They sought to take advantage of ► Tobacco industry’s efforts to open ENDS markets are bmjgh-2020-004288 the Thai Tobacco Monopoly’s (TTM) inefficiency to propose like their past efforts to liberalise closed cigarette licencing agreements and joint ventures with TTM and markets during the 1980s. Handling editor Eduardo took advantages of unclear regulations about cigarette ► The transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) at- Gómez marketing to promote their products through advertising tempts to open Thailand’s closed cigarette market in and sponsorship activities. -

Menthol Content in U.S. Marketed Cigarettes

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nicotine Manuscript Author Tob Res. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 July 01. Published in final edited form as: Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 July ; 18(7): 1575–1580. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv162. Menthol Content in U.S. Marketed Cigarettes Jiu Ai, Ph.D.1, Kenneth M. Taylor, Ph.D.1, Joseph G. Lisko, M.S.2, Hang Tran, M.S.2, Clifford H. Watson, Ph.D.2, and Matthew R. Holman, Ph.D.1 1Office of Science, Center for Tobacco Products, United States Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD 20993 2Tobacco Products Laboratory, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA Abstract Introduction—In 2011 menthol cigarettes accounted for 32 percent of the market in the United States, but there are few literature reports that provide measured menthol data for commercial cigarettes. To assess current menthol application levels in the U.S. cigarette market, menthol levels in cigarettes labeled or not labeled to contain menthol was determined for a variety of contemporary domestic cigarette products. Method—We measured the menthol content of 45whole cigarettes using a validated gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method (GC/MS). Results—In 23 cigarette brands labeled as menthol products, the menthol levels of the whole cigarette ranged from 2.9 to 19.6 mg/cigarette, with three products having higher levels of menthol relative to the other menthol products. The menthol levels for 22 cigarette products not labeled to contain menthol ranged from 0.002 to 0.07 mg/cigarette. -

Massachusetts

TOWN OF LEXINGTON MASSACHUSETTS ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Town of Lexington, Massachusetts CONTENTS TOWN GOVERNMENT Economic Development TOWN REPORT COMMITTEE Advisory Committee .......................... 96 Select Board ........................................ 3 Chair: Fence Viewers ................................... 96 Nancy C. Cowen Town Manager ..................................... 7 Fund for Lexington ............................ 97 Town Clerk/Board of Registrars ........ 10 Editorial Staff: Greenways Corridor Committee ........ 97 State Presidential Primary Election ... 11 Gloria Amirault Hanscom Area Towns Carmen Mincy Annual Town Election ........................ 19 Committees (HATS) ........................... 97 Karyn Mullins Special Town Meeting (Nov 12) ......... 22 Historical Commission ...................... 98 Susan Myerow Annual Town Meeting Minutes .......... 24 Historic Districts Commission ........... 99 Greta Peterson Senators and Representatives .......... 36 Housing Authority .............................. 99 Robert Ruxin Elected Town Officials ....................... 37 Housing Partnership Board ............. 100 Layout: Victoria Sax Moderator .......................................... 37 Human Rights Committee ............... 100 Town Meeting Members Human Services Committee ........... 101 Printer: Lexington Public Schools Association (TMMA) .......................... 38 Print Center Lexington Center Committee .......... 102 Cary Memorial Library ....................... 41 500 copies printed Lexington -

Aberrant Epithelial Differentiation by Cigarette Smoke Dysregulates Respiratory Host Defence

ORIGINAL ARTICLE BASIC SCIENCE Aberrant epithelial differentiation by cigarette smoke dysregulates respiratory host defence Gimano D. Amatngalim1,3, Jasmijn A. Schrumpf1,3, Fernanda Dishchekenian1, Tinne C.J. Mertens1, Dennis K. Ninaber1, Abraham C. van der Linden1, Charles Pilette2, Christian Taube1, Pieter S. Hiemstra 1 and Anne M. van der Does1 Affiliations: 1Dept of Pulmonology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands. 2Université Catholique de Louvain (UCL), Institut de Recherche Expérimentale & Clinique (IREC), Pôle Pneumologie, ORL & Dermatologie, Cliniques Universitaires St-Luc, Brussels, Belgium. 3Both authors contributed equally. Correspondence: Anne M. van der Does, Dept of Pulmonology, Leiden University Medical Center, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected] @ERSpublications Loss of highly expressed host defence proteins as a result of cigarette smoke-induced airway epithelial remodelling http://ow.ly/Q6Jr30iR6Jg Cite this article as: Amatngalim GD, Schrumpf JA, Dishchekenian F, et al. Aberrant epithelial differentiation by cigarette smoke dysregulates respiratory host defence. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1701009 [https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01009-2017]. ABSTRACT It is currently unknown how cigarette smoke-induced airway remodelling affects highly expressed respiratory epithelial defence proteins and thereby mucosal host defence. Localisation of a selected set of highly expressed respiratory epithelial host defence proteins was assessed in well-differentiated primary bronchial epithelial cell (PBEC) cultures. Next, PBEC were cultured at the air–liquid interface, and during differentiation for 2–3 weeks exposed daily to whole cigarette smoke. Gene expression, protein levels and epithelial cell markers were subsequently assessed. In addition, functional activities and persistence of the cigarette smoke-induced effects upon cessation were determined. -

NVWA Nr. Merk/Type Nicotine (Mg/Sig) NFDPM (Teer)

NVWA nr. Merk/type Nicotine (mg/sig) NFDPM (teer) (mg/sig) CO (mg/sig) 89537347 Lexington 1,06 12,1 7,6 89398436 Camel Original 0,92 11,7 8,9 89398339 Lucky Strike Original Red 0,88 11,4 11,6 89398223 JPS Red 0,87 11,1 10,9 89399459 Bastos Filter 1,04 10,9 10,1 89399483 Belinda Super Kings 0,86 10,8 11,8 89398347 Mantano 0,83 10,8 7,3 89398274 Gauloises Brunes 0,74 10,7 10,1 89398967 Winston Classic 0,94 10,6 11,4 89399394 Titaan Red 0,75 10,5 11,1 89399572 Gauloises 0,88 10,5 10,6 89399408 Elixyr Groen 0,85 10,4 10,9 89398266 Gauloises Blondes Blue 0,77 10,4 9,8 89398886 Lucky Strike Red Additive Free 0,85 10,3 10,4 89537266 Dunhill International 0,94 10,3 9,9 89398932 Superkings Original Black 0,92 10,1 10,1 89537231 Mark 1 New Red 0,78 10 11,2 89399467 Benson & Hedges Gold 0,9 10 10,9 89398118 Peter Stuyvesant Red 0,82 10 10,9 89398428 L & M Red Label 0,78 10 10,5 89398959 Lambert & Butler Original Silver 0,91 10 10,3 89399645 Gladstone Classic 0,77 10 10,3 89398851 Lucky Strike Ice Gold 0,75 9,9 11,5 89537223 Mark 1 Green 0,68 9,8 11,2 89393671 Pall Mall Red 0,84 9,8 10,8 89399653 Chesterfield Red 0,75 9,8 10 89398371 Lucky strike Gold 0,76 9,7 11,1 89399599 Marlboro Gold 0,78 9,6 10,3 89398193 Davidoff Classic 0,88 9,6 10,1 89399637 Marlboro Red 100 0,79 9,6 9 89398878 Lucky Strike Ice 0,71 9,5 10,9 89398045 Pall Mall Red 0,81 9,5 10,5 89398355 Dunhill Master Blend Red 0,82 9,5 9,8 89399475 JPS Red 0,81 9,5 9,6 89398029 Marlboro Red 0,79 9,5 9 89537355 Elixyr Red 0,79 9,4 9,8 89398037 Marlboro Menthol 0,72 9,3 10,3 89399505 Marlboro -

2019-Annual Report

i o aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa,,,;;,,,,„ ,,,,,,, U f a I I i l f o/ l i 0 111111III"" 1111111::::::::,111111III"" Council on Aging ............................. 102 TOWN REPORT COMMITTEE NG ERN ENT Board of Selectmen ............................. 3 Design Advisory Committee ............ 103 Chair: Economic Development Nancy C. Cowen Town Manager ..................................... 6 Advisory Committee ........................ 104 Town Clerk/Board of Registrars .......... 9 Editorial Staff: Fence Viewers ................................. 104 State Primary Election ....................... 10 Gloria Amirault Fund for Lexington .......................... 104 State Election .................................... 16 Janice Litwin Greenways Corridor Committee ...... 105 Special Town Meeting ....................... 20 Susan Myerow Hanscom Area Towns Varsha Ramanathan Annual Town Election ........................ 23 Committees (HATS) ......................... 105 Town Meeting Members .................... 26 Layout: Victoria Sax Historical Commission .................... 106 Annual Town Meeting Minutes .......... 29 Printer: Lexington Public Schools Historic Districts Commission ......... 107 Print Center Elected Town Officials ....................... 47 Housing Authority ............................ 107 Senators and Representatives .......... 48 600 copies printed Housing Partnership Board ............. 108 Moderator .......................................... 49 Also available at Human Rights Committee ............... 108 Town Meeting Members http://records.lexingtonma.gov/weblink -

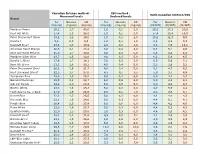

TNCO Levels and Ratio's

Canadian Intense method - ISO method - Ratio Canadian Intense/ISO Measured levels Declared levels Brand Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) Marlboro Prime 26,1 1,7 40,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 26,1 17,2 20,0 Kent HD White 17,4 1,3 28,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 17,4 13,4 14,0 Peter Stuyvesant Silver 15,2 1,2 19,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 15,2 12,3 9,5 Karelia I 9,6 0,9 9,3 1,0 0,1 1,0 9,6 8,6 9,3 Davidoff Blue* 23,6 1,7 30,9 2,9 0,2 2,6 8,3 7,0 12,1 American Spirit Orange 20,5 2,1 18,4 3,0 0,4 4,0 6,8 5,1 4,6 Kent Surround Menthol 25,0 1,7 30,8 4,0 0,4 5,0 6,3 4,3 6,2 Marlboro Silver Blue 24,7 1,5 32,6 4,0 0,3 5,0 6,2 5,0 6,5 Karelia L (Blue) 17,6 1,7 14,1 3,0 0,3 2,0 5,9 5,6 7,1 Kent HD Silver 21,1 1,6 26,2 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,3 3,9 5,2 Peter Stuyvesant Blue* 20,2 1,6 21,7 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,1 4,7 4,3 Kent Surround Silver* 22,5 1,7 27,0 4,5 0,5 5,5 5,0 3,7 4,9 Templeton Blue 25,0 1,8 26,2 5,0 0,4 6,0 5,0 4,4 4,4 Belinda Filterkings 29,9 2,2 24,7 6,0 0,5 6,0 5,0 4,3 4,1 Silk Cut Purple 24,9 2,0 23,4 5,0 0,5 5,0 5,0 4,0 4,7 Boston White 23,3 1,6 25,3 5,0 0,3 6,0 4,7 5,5 4,2 Mark Adams No. -

University of Groningen Acute Effects of Cigarette Smoking On

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Acute effects of cigarette smoking on inflammation in healthy intermittent smokers van der Vaart, Hester; Postma, Dirkje S; Timens, Wim; Hylkema, Machteld N; Willemse, Brigitte W M; Boezen, Hendrika; Vonk, Judith M; de Reus, Dorothea M; Kauffman, Henk F; ten Hacken, Nick HT Published in: Respiratory Research DOI: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-22 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van der Vaart, H., Postma, D. S., Timens, W., Hylkema, M. N., Willemse, B. W. M., Boezen, H., ... ten Hacken, N. HT. (2005). Acute effects of cigarette smoking on inflammation in healthy intermittent smokers. Respiratory Research, 6(22), [22]. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-6-22 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. -

Lexington Police Department

LEXINGTON POLICE DEPARTMENT Annual Report 2015 CONTENTS MAYOR OF LEXINGTON 2 CHIEF OF POLICE 3 4 A YEAR IN REVIEW TIMELINE SCHOOL OUTREACH PROGRAMS 6 LEXINGTON JUNIOR POLICE ACADEMY POLICE DEPARTMENT 8 D.A.R.E. PROGRAM 9 BACK PACK PROGRAM PARK AMBASSADOR PROGRAM LEXINGTON PEACE MARCHES VIOLENT CRIME INITIATIVES 10 HEALING AND LIVING ONWARD (H.A.L.O.) 11 12 WINTER STORMS TRAFFIC SAFETY AND SERVICE 13 BASKETBALL TOURNAMENTS FOURTH OF JULY 15 14 BREEDERS’ CUP 16 ROOTS & HERITAGE FESTIVAL LATINO FESTIVAL 17 THURSDAY NIGHT LIVE NATIONAL MOUNTED POLICE COLLOQUIUM 18 GOVERNOR INAUGURATION 19 NAPEC CHAMPIONSHIPS CITIZEN POLICE ACADEMY ALUMNI ASSOCIATION 20 CRIME FREE MULTI-HOUSING PROGRAM 21 RECRUITING OUTREACH 22 24 STATISTICS HISTORY OF CANINE & DEDICATION CEREMONY 26 PERSONNEL PROMOTIONS AND RETIREMENTS 28 Annual Report 2015 IN MEMORIAL - NEVER FORGET REPORT PRODUCTION 30 29 LEXINGTONKY.GOV/POLICE | PAGE 1 M MAYOR OF LEXINGTON JIM GRAY Hello, Everyone, You’re reading about a very special group of individuals in the pages of this report … people who work very hard to keep you safe in a world where safety is becoming increasingly complicated and challenging. Lexington ranks as one of the safest cities of its size in the country, thanks to our hard- working police officers. The Urban County Council and I set a high priority on making sure our police officers have the tools they need to do their jobs. Every year, public safety is the top priority in our budget. Since the start of 2011, we have invested almost $1.5 billion in public safety, and that’s a 22% increase over five years. -

Tobacco Point of Sale Advertising Increases Positive Brand User Imagery R J Donovan, J Jancey, S Jones

191 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.11.3.191 on 1 September 2002. Downloaded from RESEARCH PAPER Tobacco point of sale advertising increases positive brand user imagery R J Donovan, J Jancey, S Jones ............................................................................................................................. Tobacco Control 2002;11:191–194 Objectives: To determine the potential impact of point of sale advertising on adolescents so as to inform changes to the Tobacco Control Act. Design: Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In the control condition, See end of article for students were exposed to a photograph of a packet of cigarettes; in the intervention condition, students authors’ affiliations were exposed to an ad for cigarettes, typical of point of sale advertising posters. All students then rated ....................... the brand user on a set of 12 bipolar adjectives. Two brands were used in the study: Benson & Hedges, Correspondence to: and Marlboro. Professor Rob Donovan, Subjects: One hundred year (grade) 6 and 7 students (age range 10–12 years), from four Western Division of Health Sciences, Executive Dean’s Australian metropolitan primary schools, participated in the study. Suite, Bldg 400, Curtin Results: In a majority of the brand user descriptions, the cigarette advertisements increased brand user University, Hayman Rd, imagery in a positive way, especially for Benson & Hedges. For example, participants viewing the Bentley WA 6102, Benson & Hedges advertisement, as distinct from those viewing the Benson & Hedges pack only, were Australia; more likely to describe the Benson & Hedges user as relaxed, interesting, cool, rich, adventurous, and [email protected] classy. Relative to the Marlboro pack only, the Marlboro ad increased positive perceptions of the Marl- Received boro user on adventurous, interesting, and relaxed. -

Acute Influence of Cigarette Smoke on Secretion of Pulmonary Surfactant in Rat Alveolar Type II Cells in Culture

Eur Respir J, 1996, 9, 24–32 Copyright ERS Journals Ltd 1996 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.96.09010024 European Respiratory Journal Printed in UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 Acute influence of cigarette smoke on secretion of pulmonary surfactant in rat alveolar type II cells in culture H.R.W. Wirtz, M. Schmidt Acute influence of cigarette smoke on secretion of pulmonary surfactant in rat alveolar Dept of Medicine, University of Würzburg, type II cells in culture. H.R.W. Wirtz, M. Schmidt. ©ERS Journals Ltd 1996. Würzburg, Germany. ABSTRACT: It has been shown, that smoking results in a lower yield of surfac- tant associated phospholipids in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Indirect evidence Correspondence: H.R.W. Wirtz suggests impaired secretion. In the present study, we investigated the influence of Medizinische Klinik cigarette smoke on surfactant secretion in cultured rat alveolar type II cells. Universität Würzburg Smoke exposure was achieved by bubbling the smoke of four cigarettes through Josef Schneider Str. 2 Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) which was adjusted to a reference 97080 Würzburg absorption value of 1.36 at 320 nm. Cells were preincubated with various dilutions Germany of cigarette smoke-treated medium for 30 min, and were then exposed to this medi- um for 2 h. After this time, secretion of 3H-choline-labelled phosphatidylcholine Keywords: Antioxidants (PC) was measured as a marker of surfactant secretion. cigarette smoke A 10 fold dilution of cigarette smoke-treated medium inhibited PC secretion stimu- surfactant secretion lated by a combination of terbutaline, adenosine triphosphate and 12-O-tetrade- type II cells canoylphorbol-13-acetate by over 50%, but did not alter basal secretion. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of KENTUCKY CENTRAL DIVISION at LEXINGTON CIVIL ACTION NO.: 5:10-Cv-00390-KSF BUDS

Case: 5:10-cv-00390-KSF-REW Doc #: 79 Filed: 05/23/12 Page: 1 of 46 - Page ID#: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY CENTRAL DIVISION AT LEXINGTON CIVIL ACTION NO.: 5:10-cv-00390-KSF BUDSGUNSHOP.COM, LLC PLAINTIFF V. OPINION & ORDER SECURITY SAFE OUTLET, INC., and MATTHEW DENNINGHOFF DEFENDANTS * * * * * * * * * This matter is before the Court on the Motion filed by Defendant, Security Safe Outlet, Inc. (“SSO”) for leave to file an amended counterclaim against Plaintiff, Budsgunshop.com, LLC (“BGS”) and a third-party complaint against Marion E. Wells, Jr. (“Wells”) and Rex McClanahan (“McClanahan”) [DE #62]. The motion having been fully briefed, this matter is ripe for review. I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND & PROCEDURAL HISTORY This action stems from allegations by BGS that Defendants SSO and Matthew Denninghoff misappropriated BGS’s trade secrets by improperly accessing BGS’s customer database and obtaining and using confidential customer information, including customer email addresses, for their commercial benefit. All parties agree that SSO was formed in June 2000 by Wells, with Wells as the sole shareholder. Under the name “Bud’s Gun Shop,” SSO operated a retail store in Paris, Kentucky, selling security safes, firearms and related accessories. According to SSO, beginning in approximately 2003, SSO expanded its online business to sell firearms and related accessories through the www.budsgunshop.com website. SSO further alleges that McClanahan was hired by SSO in October 2005 to oversee and improve the company’s websites (both www.budsgunshop.com Case: 5:10-cv-00390-KSF-REW Doc #: 79 Filed: 05/23/12 Page: 2 of 46 - Page ID#: <pageID> and www.SecuritySafeOutlet.com) and SSO’s online business.