Vikalp Sangam 15Th April, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approved Capex Budget 2020-21 Final

Capex Budget 2020-21 of Leh District I NDEX S. No Sector Page No. S. No Sector Page No. 1 2 3 1 2 3 GN-0 3 29 Forest 56 - 57 GN-1 4 - 5 30 Parks & Garden 58 1 Agriculture 6 - 9 31 Command Area Dev. 59 - 60 2 Animal Husbandry 10 - 13 32 Power 61 - 62 3 Fisheries 14 33 CA&PDS 63 - 64 4 Horticulture 15 - 16 34 Soil Conservation 65 5 Wildlife 17 35 Settlement 66 6 DIC 18 36 Govt. Polytechnic College 67 7 Handloom 19 - 20 37 Labour Welfare 68 8 Tourism 21 38 Public Works Department 9 Arts & Culture 22 1 Transport & Communication 69 - 85 10 ITI 23 2 Urban Development 86 - 87 11 Local Bodies 24 3 Housing Rental 88 12 Social Welfare 25 4 Non Functional Building 89 - 90 13 Evaluation & Statistics 26 5 PHE 97 - 92 14 District Motor Garages 27 6 Minor Irrigation 93 - 95 15 EJM Degree College 28 7 Flood Control 96 - 99 16 CCDF 29 8 Medium Irrigation 100 17 Employment 30 9 Mechanical Division 101 18 Information Technology 31 Rural Development Deptt. 19 Youth Services & Sports 32 1 Community Development 102 - 138 20 Non Conventional Energy 33 OTHERS 21 Sheep Husbandry 34 - 36 1 Untied 139 22 Information 37 2 IAY 139 23 Health 38 - 42 3 MGNREGA 139 24 Planning Mechinery 43 4 Rural Sanitation 139 25 Cooperatives 44 - 45 5 SSA 139 26 Handicraft 46 6 RMSA 139 27 Education 47 - 53 7 AIBP 139 28 ICDS 54 - 55 8 MsDP 139 CAPEX BUDGET 2020-21 OF LEH DISTRICT (statement GN 0) (Rs. -

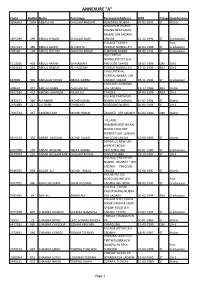

List of Candidates for Physical Efficiency Test for the Post of Wildlife/Forest Guard in Alphabetical

ANNEXURE "A" CanId RollNo Name Parentage PermanentAddress DOB CategoryQualification 9396603 1004 ABBASS ALI GHULAM HASSAN BOGDANG NUBRA 05-02-2001 ST Matric KHALKHAN MANAY- KHANG NEAR JAMA MASJID LEH LADAKH 1855389 499 ABDUL KHALIQ GHULAM NABI 194101 12-12-1994 ST Graduation VILLAGE TYAKSHI Post 1557437 389 ABDUL QADIR ALI MOHD TURTUK NUBRA LEH 30-04-1988 ST Graduation 778160 158 ABDUL QAYUM GHULAM MOHD SUMOOR NUBRA 04-02-1991 ST Graduation R/O TURTUK NURBA,DISTICT LEH, 5113265 402 ABDUL RAHIM GH HASSAN PIN CODE 194401 28-03-1996 OM 10+2 6309413 334 ABDUL RAWUF ALI HUSSAIN TURTUK NUBRA LEH 17-12-1995 RBA 10+2 CHULUNGKHA, TURTUK, NUBRA, LEH 697699 301 ABDULLAH KHAN ABDUL KARIM LADAKH-194401 02-11-1991 ST Graduation CHUCHOT GONGMA 408661 912 ABID HUSSAIN GHULAM ALI LEH LADAKH 19-12-1986 RBA Matric 4917184 412 ABIDAH KHANUM NAJAF ALI TYAKSHI 04-03-1996 RBA 10+2 VILLAGE PARTAPUR 3432671 346 ALI AKBAR MOHD KARIM NUBRA LEH LADAKH 15-07-1994 ST Matric 2535888 217 ALI SHAH GH MOHD BOGDANG NUBRA 05-05-1996 ST 10+2 7345534 337 AMAMULLAH MOHD YAQUB ZANGSTI LEH LADAKH 10-03-1999 OM Matric VILLAGE: RAMBIRPUR(THIKSAY) BLOCK:CHUCHOT DISTRICT:LEH LADAKH 6615129 355 ANSAR HUSSAIN MOHD SAJAD PIN CODE:194101 15-06-1995 ST Matric MOHALLA NEW LEH AIRPORT ROAD 6952008 107 ANSAR HUSSAIN ABDUL KARIM SKALZANGLING 01-01-1989 ST Graduation 4370703 255 ANSAR HUSSAIN MIR GHULAM MOHD DISKET NUBRA 23-10-1997 ST 10+2 VILLAGE: PARTAPUR NUBRA DISTRICT : LEH LADAKH PIN CODE: 9346395 993 ASGAR ALI MOHD ISMAIL 194401 25-06-1997 ST Matric HOUSE NO 102 NORGYASLING LEH Post -

Ahf Snow Leopard Exploratory Simon Balderstone

ahf snow leopard exploratory simon balderstone trip highligh ts Small group limited to seven guests, ideal for wildlife viewing Carefully researched itinerary to include exploration in Rumbak and the remote Hemis Shukpachan valley Top guides from the Snow Leopard Conservancy (Ladakh) High quality gear including tents ‑ with heated mess tent ‑ along with sleeping bags, inner bags & down jackets Trip escorted by AHF Chair Simon Balderstone Trip Duration 15 days Trip Code: SL2 Grade Introductory to Moderate Activities day walks Summary 15 day trip, 6 nights hotel, 3 nights comfortable lodge, 5 nights camping welcome to why travel with World Expeditions? When planning travel to a remote and challenging destination, many World Expeditions factors need to be considered. World Expeditions have been pioneering Thank you for your interest in our AHF Snow Leopard trek. At treks in the Indian Himalaya since 1975. Our extra attention to detail World Expeditions we are passionate about our off the beaten track and seamless operations on the ground ensure that you will have experiences as they provide our travellers with the thrill of coming a memorable trekking experience in the Himalaya. Every trek is face to face with untouched cultures as well as wilderness regions accompanied by an experienced local leader who is highly trained in of great natural beauty. We are committed to ensuring that our remote first aid, as well as knowledgeable crew that share a passion unique itineraries are well researched, affordable and tailored for the for the region in which they work, and a desire to share it with you. We enjoyment of small groups or individuals ‑ philosophies that have take every precaution to ensure smooth logistics. -

Registration No

List of Socities registered with Registrar of Societies of Kashmir S.No Name of the society with address. Registration No. Year of Reg. ` 1. Tagore Memorial Library and reading Room, 1 1943 Pahalgam 2. Oriented Educational Society of Kashmir 2 1944 3. Bait-ul Masih Magarmal Bagh, Srinagar. 3 1944 4. The Managing Committee khalsa High School, 6 1945 Srinagar 5. Sri Sanatam Dharam Shital Nath Ashram Sabha , 7 1945 Srinagar. 6. The central Market State Holders Association 9 1945 Srinagar 7. Jagat Guru Sri Chand Mission Srinagar 10 1945 8. Devasthan Sabha Phalgam 11 1945 9. Kashmir Seva Sadan Society , Srinagar 12 1945 10. The Spiritual Assembly of the Bhair of Srinagar. 13 1946 11. Jammu and Kashmir State Guru Kula Trust and 14 1946 Managing Society Srinagar 12. The Jammu and Kashmir Transport union 17 1946 Srinagar, 13. Kashmir Olympic Association Srinagar 18 1950 14. The Radio Engineers Association Srinagar 19 1950 15. Paritsarthan Prabandhak Vibbag Samaj Sudir 20 1952 samiti Srinagar 16. Prem Sangeet Niketan, Srinagar 22 1955 17. Society for the Welfare of Women and Children 26 1956 Kana Kadal Sgr. 1 18. J&K Small Scale Industries Association sgr. 27 1956 19. Abhedananda Home Srinagar 28 1956 20. Pulaskar Sangeet Sadan Karam Nagar Srinagar 30 1957 21. Sangit Mahavidyalaya Wazir Bagh Srinagar 32 1957 22. Rattan Rani Hospital Sriangar. 34 1957 23. Anjuman Sharai Shiyan J&K Shariyatbad 35 1958 Budgam. 24. Idara Taraki Talim Itfal Shiya Srinagar 36 1958 25. The Tuberculosis association of J&K State 37 1958 Srinagar 26. Jamiat Ahli Hadis J&K Srinagar. -

Climate Change Invasive Species Visitor Displacement Mexico, India INTERNATIONAL Journal of Wilderness

Climate Change Invasive Species Visitor Displacement Mexico, India INTERNATIONAL Journal of Wilderness AUGUST 2009 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 2 FEATURES SCIENCE and RESEARCH EDITORIAL PERSPECTIVES 23 Displacement in Wilderness Environments 3 Wilderness in a Word … or Two … or More A Comparative Analysis BY VANCE G. MARTIN BY JOHN G. PEDEN and RUDY M. SCHUSTER PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ALDO SOUL OF THE WILDERNESS LEOPOLD WILDERNESS RESEARCH 4 The Hidden Wildness of Mexico INSTITUTE 30 WILD9 and Wilderness Science BY JAIME ROJO BY GEORGE (SAM) FOSTER STEWARDSHIP EDUCATION and COMMUNICATION 7 The Nature of Climate Change 31 A Profile of Conservation International Reunite International Climate Change BY RUSSELL A. MITTERMEIER, CLAUDE Mitigation Efforts with Biodiversity GASCON, and THOMAS BROOKS Conservation and Wilderness Protection BY HARVEY LOCKE and BRENDAN MACKEY 14 Key Biodiversity Areas in Wilderness INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES BY AMY UPGREN, CURTIS BERNARD, ROB P. 35 Mountain Ungulates of the Trans-Himalayan CLAY, NAAMAL DE SILVA, MATTHEW N. Region of Ladakh, India FOSTER, ROGER JAMES, THAÍS KASECKER, BY TSEWANG NAMGAIL DAVID KNOX, ANABEL RIAL, LIZANNE ROXBURGH, RANDAL J. L. STOREY, and KRISTEN J. WILLIAMS WILDERNESS DIGEST 41 Announcements 18 Alien and Invasive Species in Riparian Plant Communities of the Allegheny River Islands Book Reviews Wilderness, Pennsylvania 45 Roadless Rules: The Struggle for the Last BY CHARLES E. WILLIAMS Wild Forests BY TOM TURNER 45 Yellowstone Wolves: A Chronicle of the Animal, the People, and the Politics BY CAT URBIGKIT Disclaimer On the Cover The Soul of the Wilderness column and all invited and featured articles in IJW, are a FRONT: Green parakeet flock (Aratinga holochlora) forum for controversial, inspiring, or especially at the Sotano de las Golondrinas cave, San Luis Potosi, informative articles to renew thinking and Mexico. -

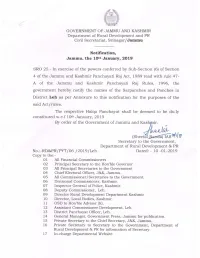

SRO-25, District Leh-Name of Panches and Sarpanches

Annexture to Notification , SRO________________dated_________________ 25 10 JAN-2019 S.No District Sr. No & S.No & Name of the Panchayat Name of the Sarpanch Sr. No and Name of panch Name of the Elected Panch with Parentage name of Elected with constitencies Block Parentage LeH 3-Durbuk PH-01 Chuchul Tsering Dolkar D/O 1 Chuchul Lundup Namgail S/O Rinchen Morup ,, ,, Phanday Nima 2 Chuchul Tsering Yangzom W/O Konchok Stanzin ,, ,, 3 Chuchul Tashi Paljor S/O Konchok Stanzin ,, ,, 4 Chuchul Sonam Paljor S/O Konchok Tsering ,, ,, 6 Chuchul Sonam Morup S/O Tundup Tashi ,, ,, 7 Youl Namgail Phunchok S/O Tsewang Rigzen 3-Durbuk PH-02 Durbuk Konchok Namgyal S/O 1 Punpun Tsering Dorjay S/O Tsewang Tundup ,, ,, Tsering Norbu 3 Laga Stanzin Pasang S/O Tsering Motup ,, ,, 4 Shayok Lobzang Tsering S/O Ranchan Samstan ,, ,, 5 Nimgo Stanzin Dolkar W/O Tsewang Gyalson ,, ,, 6 Nimgo Namgyal Andus S/O Tashi Rigzin ,, ,, 7 Rellay Singay Jamphel S/O Nawang Dorjay 3-Durbuk PH-03 Kargyam Konchok Punchok S/o 1 Kargyam Tsering Norbu S/o Dorjey Gyaltson ,, ,, Tashi Tsering 2 Kargyam Tsering Chuskit W/o Tsering Angdu ,, ,, 3 Satto Tashi Tsering S/o Dorjay Namgyal ,, ,, 4 Satto Mutup Dorjay S/o Dorjay Tundup ,, ,, 5 Kherapullu Tashi Dolkar W/o Tashi Dorjay ,, ,, 6 Satto Chamba Namdol S/o Sonam Jorgias ,, ,, 7 Kherapullu Sonam Murup S/o Konchok Chozang 3-Durbuk PH-04 Maan Pangong-A Deachen Dolker D/o 1 Khakteth Thinlay Angchuk S/o Mephem Therchen ,, ,, Tsering Namgail 2 Merak Yokma Rinchen Dolker W/o Kunzang Paljor ,, ,, 3 Merak-Gongma Phunchok Nurboo S/o Sonam -

Snow Leopard Special: Ladakh

Snow Leopard, Hemis National Park (Mike Watson). SNOW LEOPARD SPECIAL: LADAKH 1 – 14/17 MARCH 2017 LEADERS: MIKE WATSON & JIGMET DADUL. 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Snow Leopard Special: Ladakh 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com Snow Leopard guarding its Blue Sheep kill in Hemis NP (Mike Watson). Our ffth visit to the mountains of Ladakh in search of Snow Leopards was another success and resulted in two sightings, involving maybe two different cats, however, the second of these was certainly our most prolonged close range encounter so far involving a leopard at its Blue Sheep kill over the course of three days! Many thousands of images later we felt we could hardly better it so we did not spend quite as much time scanning as usual and looked for other animals instead. This resulted in a longer bird and mammal list than last time when we spend many more hours at vantage points. Other mammalian highlights included: two sightings of Grey (or Tibetan) Wolf; Siberian Ibex; Urial, Ladakh’s endemic ‘red sheep’; any amount of Blue Sheep (or Bharal), the Snow Leopard’s favourite prey, as well as other hardy alpine inhabitants such as Woolly Hare, Mountain Weasel and (Tibetan) Red Fox. The Tibetan Plateau Extension added Argali (the world’s largest sheep) and Kiang (Tibetan Wild Ass). Billed as a joint Birdquest/Wild Images tour, our birders were happy with a good selection of old favourite Himalayan specialities including: Himalayan Snowcock, Lammergeier, Himalayan Griffon Vulture, Golden Ea- gle, Ibisbill, Solitary Snipe (three plus another while acclimatizing pre-tour), Hill and Snow Pigeons, Eurasian Eagle Owl, Red-billed and Alpine Choughs, White-browed Tit-Warbler (six), Wallcreeper, Güldenstädt’s Red- start, Brown Dipper, Robin and Brown Accentors, Brandt’s Mountain Finch, Streaked and Great Rosefnches, Twite and Red-fronted Serin on the main tour. -

List of Registered Travel Agents in Leh

List of Registered Travel Agents in Leh. o N Name of Travel Agent Address Phone No. & Fax No. S 1 4 Season Tour Zangsti, Leh 2 Active Adventure Digger Nubra, Leh 01982 - 254841 3 Adventure Hill Old Road, Leh 01982 - 252058 01982 - 256255 4 Adventure Holiday Skara, Leh M. 9419612052 01982 - 269385 5 Adventure Infinite Tours & Travel Stok M. 9419178319/9419818444 Dragon Hotel, 01982 - 252139 6 Adventure North Old Road, Leh F. 252720 7 Adventure Sky Pillar Fort Road, Leh 01982 - 252089 8 Adventure Tours Leh 01982 - 9 Adventure Travel House Fort Road, Leh 10 Adventure Trek Icher Zanskar 11 Adventure Wildlife Tour & Travel Gonpa, Leh Fax. 256068 12 Adventure Zanskar Tsagar, Zanskar 13 Alpine Trek & Tours Leh 01982 - 252454/252580 01982 - 255012 14 Alps Adventure Leh M. 9419178116 15 Amitabha Tour & Travels Shenam, Leh 01982 - 252900 16 Ancient Tracks Tingmosgang (Zangsti) 01982 - 250505 17 Antilope Tours & Travel Fort Road, Leh 01982 - 253527/252086 18 Apex Adventure Tours Nimoo, Leh 01982 - 255451 19 Aravan Tribles Tours Phyang, Leh 01982 - 256187 20 Aryian Kingdom Adventure Tours 21 Atisha Travels Fort Road, Leh 01982 - 253182 22 Aventure - La Tar & Temisgam M. 946960035 23 Babu Travels Phyang, Leh 01982 - 256223 24 Bodhi Travel Leh M. 9858809201 25 Broken Moon Trek & Tour Chuchot 01982 - 250242 26 Caravan Himalayas Leh M. 9906988801 27 Caravan Travel Leh 01982 - 252282 28 Caravan Travels & Tours Leh 29 Chamba Tours & Travels Chamshen, Nubra 01980 - 267005 30 Changthang Adventure Expedition Main Bazar, Leh 01982 - 252036/252179 31 Chonjor Tours & Travels Leh 01982 - 252375 32 Choskor Tours & Travels Hotel Choskor, Leh 01982 - 252462 01982 - 251898 33 Chumik Travel Matho M. -

Demographic Status and Household of Leh District in the Year 2018

Demographic Status and HouseHold of Leh District in the Year 2018. No. Of House Population S.No. Name of the Blocks/Ward Sex Ratio Hold Male Female Total 1 Leh 2822 7833 7860 15693 1003 2 Nimmo 828 2813 2836 5649 1008 3 Saspol 572 1919 1810 3729 943 4 Khaltsi 817 3151 3129 6280 993 5 Skurbuchan 878 3116 3074 6190 987 6 Singaylalok HQ at Wanla 330 772 786 2256 1018 7 Diskit 1384 3513 3457 6970 984 8 Turtuk 921 3317 3180 6497 959 9 Panamic 1330 3431 3309 6740 964 10 Nyoma 1023 2779 2707 5486 974 11 Rupsho HQ at Puga 289 834 807 1641 968 12 Rong HQ at Chumathang 438 1266 1261 2527 996 13 Durbuk 767 2664 2615 5279 982 14 Kharu 1474 4191 4497 8688 1073 15 Chuchot 1847 5180 4894 10074 945 16 Thiksay 785 2853 2521 5374 884 Total-I: 16505 49632 48743 99073 982 17 Leh Town 3246 7763 8048 15811 1037 Total-II: 3246 7763 8048 15811 1037 G.Total I+II: 19751 57395 56791 114884 989 Source:- Chief Medical Office, Leh. Village-Wise Demographic Status of Leh District in the Year 2018. Total Population S.No. Name of Block/ Village HouseHold Male Female Total Block:Rong HQ at Chumathang 1 Liktsey 94 86 180 31 2 Tukla 80 85 165 31 3 Tukla phulak 67 76 143 24 4 Tarchet 100 110 210 38 5 Hemya 113 97 210 37 6 katpu 24 28 52 11 7 kunggam 162 141 303 47 8 Teri 103 101 204 30 9 Gaik 4 7 11 2 10 Kumdok 46 60 106 18 11 Keairy 31 39 70 14 12 Nee 51 39 90 18 13 Sriyoul 24 29 53 10 14 Kesar 50 54 104 17 15 Skidmang 108 95 203 36 16 Chumathang 209 214 423 74 Total:- 1266 1261 2527 438 Block:Rupsho HQ at Puga Male Female Total HH 1 Mahey 22 33 55 18 2 Kharnak 67 78 145 -

Ladakh: 26 May—26 June 2004 Otto Pfister Transversal 1 Este #57-42, Bogota D

Indian Birds Vol. 1 No. 3 (May-June 2005) 57 Ladakh: 26 May—26 June 2004 Otto Pfister Transversal 1 Este #57-42, Bogota D. C., Colombia. Email: [email protected] Introduction improved in the valleys towards end of June, 30: Walk along the river from Leh up to y wife accompanied me on my tenth whereas water level at Startsapuk-Tso Horzey (3,840m). Sunny and warm. Mvisit to Ladakh. The main objectives remained extremely low with the main feeder 31: Leh. Sunny and warm. of this trip included updating Ladakh wildlife streams dry and the spillover connection 1 June: Dropped at Zinchan (3,250m) and records, especially mammal and breeding into Tso-Kar barren. The low water table walked up to Rumbak village (4,000m). bird observations, photography, and offered apparently favorable breeding Cloudy and windy. Rumbak cold and promoting my forthcoming book ‘Birds and conditions to Great Crested Grebes snowing. Mammals of Ladakh’(launched by end of Podiceps cristatus in Startsapuk-Tso where 2-6: Rumbak and surroundings including June 2004). Book promotional activities a remarkably high number of about 100 nests Stock-La base (4,600m), Hussing Nullah forced us to spend excessive time in Leh were counted. In addition, some 30 Black- (4,000-4,500m) and Yurutse (4,200m) town. Our fieldwork, however, concentrated necked Grebes Podiceps nigricollis were towards Ganda-La (4,500m). Generally on areas north of Leh, the Shey-Tikse observed in the same lake about three weeks overcast and windy, cold including snow marshes, the Rumbak area in Hemis National later (M. -

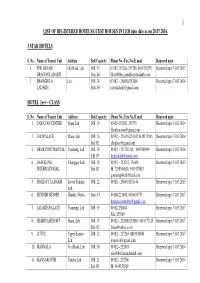

1 LIST of REGISTERED HOTELS/GUEST HOUSES in LEH Upto Date As on 20.07.2016

1 LIST OF REGISTERED HOTELS/GUEST HOUSES IN LEH upto date as on 20.07.2016. 3 STAR HOTELS S. No. Name of Tourist Unit Address Bed Capacity Phone No. /Fax No./E.mail Renewed upto 1. THE GRAND Old Road, Leh D R. 53 01982-255266, 257786, 9419178239 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 DRAGON LADAKH Suits 06 Hotel@the granddragonladakh.com 2. SHANGRILA Leh D R. 24 01982 – 256050/253869 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 LADAKH Suits 03 [email protected] HOTEL (A+) – CLASS S. No. Name of Tourist Unit Address Bed Capacity Phone No. /Fax No./E.mail Renewed upto 1. CARAVAN CENTRE Skara Leh D R. 29 01982-252282, 253779 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 [email protected] 2. CHO PALACE Skara, Leh. D R. 26 01982 – 251659/251142,9419179565 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 Suit 02 [email protected] 3. DRUK CONTINENTAL Yourtung, Leh D R. 38 01982 – 251702, M: - 9697000999 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 S R. 03 [email protected] 4. GAWALING Changspa, Leh. D R. 18 01982 – 253252, 256456 Renewed upto 31.03.2013 INTERNATIONAL Suit 02 M. 7298540620, 9419178813 [email protected] 5. HOLIDAY LADAKH Lower Tukcha, D R. 22 01982 – 250403/251444 Renewed upto 31.03.2013 Leh. 6. HUNDER RESORT Hunder, Nubra Suits 15 01980-221048, 9469453757 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 [email protected] 7. LADAKH PALACE Yourtung, Leh D R. 19 01982-258044 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 Fax. 255989 8. LHARISA RESORT Skara, Leh. D R. 15 01982 – 252000/252001, 9419177425 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 Suit 02 [email protected] 9. -

Ab Rashid Wani Ab Majeed Wani Katrusoo Phe 3/30/1979 Daily Rated Workers/Work Charged Employees Kulgam Shahzad Ahmad Mohd

DAILY RATED WORKERS/WORK AB RASHID WANI AB MAJEED WANI KATRUSOO PHE 3/30/1979 CHARGED EMPLOYEES KULGAM SHAHZAD AHMAD MOHD AMIN WANI PUMBAY PHE 1/15/1989 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM ASIF SHEERAZ SHEERAZ AH SHEIKH SHALIPORA PHE 2/1/1977 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM DAILY RATED WORKERS/WORK MOHD AYOUB RESHI MOHD MAQBOOL RESHI KAHAROTE PHE 11/9/1976 CHARGED EMPLOYEES KULGAM DAILY RATED WORKERS/WORK IMTIYAZ AHAMD DAR GH HASSAN DAR PARIGAM PHE 3/3/1976 CHARGED EMPLOYEES KULGAM DAILY RATED WORKERS/WORK MUSHTAQ AHMAD SHAH GH HASSAN SHAH AMNOO PHE 3/3/1971 CHARGED EMPLOYEES KULGAM SUBZAR AH DAR MOHD ABDULLAH DAR ARREH PHE 7/4/1977 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM BASHIR AH BHAT AB KABIR BHAT MANCHU PHE 6/20/1968 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM DAILY RATED WORKERS/WORK ASHAQ HUSSAIN WAGAY GH MOHD WAGAY BATPORA PHE 2/1/1985 CHARGED EMPLOYEES KULGAM DAILY RATED WORKERS/WORK REYAZ AHADM ITOO ALI MOHD ITOO CHOWALGAM PHE 3/30/1972 CHARGED EMPLOYEES KULGAM BILAL AH GANIE MOHD AMIN GANIE KANDIPORA KULGAM PHE 2/24/1983 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM DAILY RATED WORKERS/WORK MOHD RAMZAN PARRY AB AHAD PARRY SUNIGAM PHE 3/30/1973 CHARGED EMPLOYEES KULGAM MOHD AKBAR NAIL AB GANI NAIK BADJIHALAN PHE 5/6/1991 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM IMRAN RASOOL DAR BARKAT RASOOL DAR KOREL PHE 3/3/1990 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM IMTIYAZ AHMAD BHAT MOHD SADIQ BHAT MIRHAMA PHE 4/1/1990 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM JAVID AHMAD SHAH MOHD YASIN SHAH BRAZLOO KULGAM PHE KULGAM 5/15/1975 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM MOHD IDREES MIR AB REHMAN MIR CHAKI WATOO PHE 2/28/1990 CASUAL LABOURERS KULGAM SUBZAR AH KHAN MOHD AKBAR KHAN GUDDER