1 Co-Evolution of Policies and Firm Level Technological Capabilities in the Indian Automobile Industry Dinar Kale ESRC Innogen C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daewoo Trucks

Design Your Daewoo DAEWOO TRUCKS DesignDesign YourYour DaewooDaewoo Daewoo Trucks was newly launched in 2004, Daewoo Trucks provides unique experience to its customers by listening to their needs Daewoo Trucks is continuously striving to become a global commercial and reflecting them in its product development. vehicle company through“Relentless innovation that impacts the world.” With this rebirth, Daewoo Trucks strives to become one of the most respected companies in Korea for the commercial vehicle industry. “Design Your Daewoo”represents our product identity; the regionally customized products will make us competitive in the rapidly changing circumstances. Let’s design your own DAEWOO for successful business. And with“Design Your Daewoo”, we will become the best commercial vehicle maker to achieve the goals which looked impossible and to make everyone realize their dreams. 02 DESIGN YOUR DAEWOO DESIGN YOUR DAEWOO 03 CEO MESSAGE Design Your Daewoo, Daewoo Trucks Daewoo Trucks provides value to Daewoo Trucks has identified local Having sold almost 50,000 units in customers exceeding their expecta- production in key markets as a sig- the international markets over the tions by offering preferred products nificant strategy lever to achieve its last 10 years, we strive to sell fur- and services. We also enhance goals. Accordingly we have overseas ther 50,000 units in the next 5 years. stakeholder value with focus on assembly and production Bases in sustainable, profitable growth. Pakistan, Russia, Algeria, Vietnam, We are confident executing our Kenya and South Africa to cater to plans will help us enhance our status Daewoo Trucks continuously strives the respective local markets. -

The Grand Project Study on a PERCEPTION of PEOPLE on ³NANO´ CAR Based on Customer Survey

The grand project study on a PERCEPTION OF PEOPLE ON ³NANO´ CAR based on customer survey. The main objectives of the project are ! To know the perception of people about ³NANO´ car in Baroda city. ! To know about awareness of products. ! To know about factors affecting purchase decision of ³NANO´. ! To know how purchase decision of ³NANO´.varies from different Income group. For this project customer research was carried out at various area of Baroda City. In this customer research, I learnt about different types of customer¶s perception about TATA´s NANO in Baroda City. 1 JOSEPH SCHOOL OF BUSINESS STUDIES (SHIATS) C,B. MISHRA INDEX Sr. NO. CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. INDUSTRY PROFILE 2. COMPANY PROFILE 3. THEORITICAL BACKGROUND 4. IDENTIFICATION OF THE STUDY 5.1 MARKETING RESEARCH PROBLEM 5.2 SCOPE OF THE STUDY 5.3 OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY 5.4 LIMITATION OF THE STUDY 5. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 6. INTERPRETATION AND ANALYSIS 6. INTERPRETATION OF RESULTS 7. CONCLUSION 9 ANNEXURE 9.1 BIBLIOGRAPHY 2 JOSEPH SCHOOL OF BUSINESS STUDIES (SHIATS) C,B. MISHRA TATA GROUP PROFILE: THE TATA GROUP COMPRISES 98 OPERATING COMPANIES IN SEVEN BUSINESS SECTORS: INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND COMMUNICATIONS; ENGINEERING; MATERIALS; SERVICES; ENERGY; CONSUMER PRODUCTS; AND CHEMICALS. THE GROUP WAS FOUNDED BY JAMSETJI TATA IN THE MID 19TH CENTURY, A PERIOD WHEN INDIA HAD JUST SET OUT ON THE ROAD TO GAINING INDEPENDENCE FROM BRITISH RULE. CONSEQUENTLY, JAMSETJI TATA AND THOSE WHO FOLLOWED HIM ALIGNED BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES WITH THE OBJECTIVE OF NATION BUILDING. THIS APPROACH REMAINS ENSHRINED IN THE GROUP'S ETHOS TO THIS DAY. -

The Positioning Disaster of Tata Nano: a Case Study On

IJMH - International Journal of Management and Humanities ISSN: 2349-7289 THE POSITIONING DISASTER OF TATA NANO: A CASE STUDY ON TATA NANO Ashik Makwana1 | Prof Nishit Sagotia2 1(Student, MBA Semester 09, Noble Group of Institutions, Junagadh, Gujarat, [email protected]) 2(Assistant Professor, Dept of Management, Noble Group of Institutions, Junagadh, Gujarat, [email protected]) ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract— The Indian auto industry is one of the largest in the world. The industry accounts for 7.1 per cent of the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The Two Wheelers segment with 80 per cent market share is the leader of the Indian Automobile market. Tata Motors Limited is a leading global automobile manufacturer of cars utility vehicles buses trucks and defence vehicles. Tata Nano popularly known as people‘s car was launched at such time when India‘s largest car company known for its cost effective products Maruti Suzuki was pondering upon the strategic option of discontinuing the production of the than available cheapest car of Indian Market and it flagship product Maruti Suzuki 800. This case is selected as per following basis: Case is related with marketing Mix, positioning of the product and brand equity, to understand what went wrong with Nano, to understand the concept of Positioning, to understand how marketing mistakes makes a product to failure, to find alternatives for the solutions. Following are the sources of data collection: Articles and review of students and people and Dr. Vivek Bindra’s videos. Following are the assumptions of the case study: the company will continue its product in the market, the collected data is correct. -

Nano-The People's

International Journal of Research in Management ISSN 2249-5908 Issue2, Vol. 2 (March-2012) Nano-The People’s Car Name first author-Dr. Binod Kumar Singh Designation –Faculty Member Address-Dr. Binod Kumar Singh, Faculty Member,Amity Global Business School,Patna E-mail id- [email protected], [email protected] Mobile No.-+91-9430602830, +91-9204055893 ___________________________________________________________________________ Author Profile I did Ph.D. (Statistics) from Faculty of Science, Banaras Hindu University and Diploma in Information Technology from R.C.S.M.I had seven years of teaching experience. Seven of my papers were published in International and eleven were published in National Journal. I have attended number of international conferences. I have been nominated Member Editorial Board for the Journal of Bioinformatics and Sequence Analysis (JBSA), African Journal of Business Management (Impact factor 1.015) and International Journal on Business Management, Finance, Human Resource, Marketing and Economics (ISI Index Journal), Asian Journal of Marketing,(ISI index journal), Research Journal of Business Management(ISI index journal), Asian Journal of Mathematics and Statistics(ISI index journal), Singapore Journal of Scientific Research(ISI index journal) and Journal of Economics & International Finance, ISSN:2006-9812(ISI index journal. Vice-Chancellor of Central University of Jharkhand, Ranchi has been nominated me to act as an expert member in the selection committee meeting for the post of Jr. System Executive. I have been selected in the panel of experts in a round table discussion held on 10 February 10, 2010, entitled "Denmark: Better, Faster, Stronger - Leading the Way in Translational Medicine‖. I have been also selected in the panel of experts in a round table discussion held on 10 December 2008, entitled, "State of the Nation: Science in Ireland.‖ My thrust areas are Statistics, Quantitative Methods, Marketing Research, Research Methodology and Operation Management. -

Automobile Industry in India 30 Automobile Industry in India

Automobile industry in India 30 Automobile industry in India The Indian Automobile industry is the seventh largest in the world with an annual production of over 2.6 million units in 2009.[1] In 2009, India emerged as Asia's fourth largest exporter of automobiles, behind Japan, South Korea and Thailand.[2] By 2050, the country is expected to top the world in car volumes with approximately 611 million vehicles on the nation's roads.[3] History Following economic liberalization in India in 1991, the Indian A concept vehicle by Tata Motors. automotive industry has demonstrated sustained growth as a result of increased competitiveness and relaxed restrictions. Several Indian automobile manufacturers such as Tata Motors, Maruti Suzuki and Mahindra and Mahindra, expanded their domestic and international operations. India's robust economic growth led to the further expansion of its domestic automobile market which attracted significant India-specific investment by multinational automobile manufacturers.[4] In February 2009, monthly sales of passenger cars in India exceeded 100,000 units.[5] Embryonic automotive industry emerged in India in the 1940s. Following the independence, in 1947, the Government of India and the private sector launched efforts to create an automotive component manufacturing industry to supply to the automobile industry. However, the growth was relatively slow in the 1950s and 1960s due to nationalisation and the license raj which hampered the Indian private sector. After 1970, the automotive industry started to grow, but the growth was mainly driven by tractors, commercial vehicles and scooters. Cars were still a major luxury. Japanese manufacturers entered the Indian market ultimately leading to the establishment of Maruti Udyog. -

MBA Department at the University of Pune

Annexure A-Covering letter Dear Respondent I am working as an Assistant Professor in PES's Modem College of Engineering -MBA Department at the University of Pune. Currently I am pursuing Doctoral Research under the guidance of Prof Dr. G.K. Shirude-Director, Naralkar Institute of Career Development and Research. The topic of my research is "A Study of supply chain management system of Auto Industries in Pune Region with reference to Passenger Car Segment. The questionnaire has been designed in such a way that it will not consume much of your precious time. Most of the questions can be answered by simply making a tick in a box. Kindly fill the questionnaire and in a way give me a helping hand towards the completion of my Research work. • This is an independent research study and participation is voluntary. Your responses will be treated as strictly confidential and the anonymity of companies and respondents is assured. • No person or firm will have access to your conq)leted questionnaire. Should you require a copy of the abbreviated report of the findings please write your name, email address or telephone number at the end of the questionnaire. I look forward to your positive response. Yours sincerely Shraddha Khoje Research Student /-f • Annexure B; Survey auestionnaire SECTION 1: GENERAL INFORMATION Company Profile 1. Name of Company 2. Address 3. Tel 4. Fax 5. Website 6. Contact person: 7. E-mail: 8. Position in conpany: No of employees: [ ] Turnover : f 9. Yearofestablishment- 10. Indicate which of the following is/are your target customer(s) and the number of years your company has been supplying this market. -

Starter Motor

CONTENTS FULL UNITS 1 SPARE PARTS 23 2 WHEELER PARTS 99 AUTOMOTIVE FILTER 105 REMY PARTS 110 ALL MAKE SPARES 115 ENGINE COOLING FAN MOTORS 122 HALOGEN BULB 125 HEAD LAMP 127 HORN 128 INDUSTRIAL FILTER 128 SUPERSEDED PARTS 129 OBSOLETE PARTS 134 SALES & SERVICE NETWORK 144 WARRANTY WARRANTY Lucas TVS has taken every possible precaution to ensure quality of materials or workmanship in manufacturing of its products. In the event of any defects noticed within twelve months or 20,000 kilometers, whichever is earlier of its being put into use, Lucas TVS will either repair or replace components in exchange for those defective components under warranty at free of cost. This warranty does not cover misuse, modification, improper application, abuse, accident or negligence and failure of our products working in conjunction with non Lucas TVS Products. Also excluded from this warranty are parts which are subject to normal wear and tear, any labour cost incurred for removal and refitting to the vehicle or engine, and any other consequential expenses. The purchaser should contact the outlet where they originally purchased the product and should provide the purchase receipt, repair order or other proof that the product is within the warranty period, this will be required in order to honor the warranty claim. Lucas TVS reserve the right to refuse to consider claims if the components have been subject to repair or adjustment, and failures caused by unauthorized services or any component is returned incomplete. TERMS & CONDITIONS OF SALE TERMS & CONDITIONS OF SALE This revised edition supersedes all lists, amendments and additions earlier and is effective from 3rd October 2017 Price Bulletin upto 94/2017 are included in this book. -

Behind the Nano Mistakes : a Case Study on Consumer Psychology

CASE STUDY Behind the Nano Mistakes : A Case Study on Consumer Psychology Shamim Akhtar Abstract Since from its conception, there have been way too many impediments towards Faculty Member Icfai University the success of Tata Motors dream project – Nano. It seems evident that Tatas Mizoram have had problems with the entire marketing mix for Nano. There were initial safety issues with the product; they couldn’t hold on to their original pricing promise due to rising costs; there was a tough time with the distribution due to serious mismatch between demand and supply; and there wasn’t a proper promotional campaign to begin with. This explorative case study looks beyond the mistakes and attempts to throw light on the consumer psychology regarding Nano’s initial low market acceptance; which seemed to be quite different from what the company and industry had speculated in the beginning. While making qualitative assessment of the perception, attitudes and behavior of the consumers, the case study also explores the continuous hurdles that Tata Motors had gone through and the others that it still tries to overcome to ensure “Nano – the people’s car”, gets its truly deserving position in the market. “We are happy to present the People’s Car to India and we hope it brings the joy, pride and utility of owning a car to many families who need personal mobility.” – Ratan Tata after unveiling Nano at the 2008 Delhi Auto Expo1 “I think it’s a moment of history and I’m delighted an Indian company is leading the way.” – Anand Mahindra, Managing Director, Mahindra & Mahindra Quoted by Hindustan Times before the unveiling of Nano2 “There was a mismatch vis-à-vis the hype. -

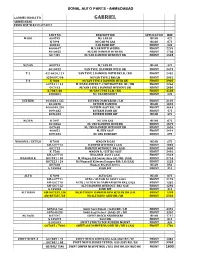

Gabriel India Ltd Gabriel Ahmedabad Price List W.E.F 01.07.2017

SONAL AUTO PARTS - AHMEDABAD GABRIEL INDIA LTD GABRIEL AHMEDABAD PRICE LIST W.E.F 01.07.2017 PART NO DESCRIPTION APPLICATION MRP M 800 600795 M/ CAR 89 REAR 421 K 7096 M/CAR 96 GAS REAR 673 400012 CAR BUSH KIT FRONT 223 4000047 M/CAR WITH SPRING FRONT 2239 4010055 M/CAR DAMPER WITH BK FRONT 1708 G0 7437 M/CAR DAMPER WITHOUT BK FRONT 1528 M/VAN 600793 M/ VAN 89 REAR 421 4010022 VAN TYPE 1DAMPER WITH BK FRONT 2473 T-2 4210020 / 21 VAN TYPE 2 DAMPER WITH BK LH / RH FRONT 2482 4200007/06 M/VAN TYPE 2 RH/LH FRONT 3031 T-3 K 7086 M/VAN TYPE 3 DAMPER WITK BK FRONT 2905 G07441 / 42 M/VAN DAMPER T-2 WITHOUT BK LH / RH FRONT 2266 G07443 M/VAN TYPE 3 DAMPER WITHOUT BK FRONT 2680 K 7087/88 M/VAN TYPE 3 LH / RH FRONT 3508 4200001 M/ VAN BUSH KIT FRONT 223 ESTEEM 4010031 /32 ESTEEM DAMPER RH / LH FRONT 2104 4010028 ESTEEM DAMPER REAR 1825 4000049 /50 ESTEEM ASSY RH / LH FRONT 3643 4094182 ESTEEM BUSH KIT FRONT 475 4094183 ESTEEM BUSH KIT REAR 475 M/ZEN K 7097 M/ ZEN GAS REAR 673 4010056 M/ ZEN DAMPER WITK BK FRONT 1879 G07438 M/ ZEN DAMPER WITHOUT BK FRONT 1654 400052 M/ZEN ASSY FRONT 2419 4094181 M/ ZEN BUSH KIT FRONT 295 WAGON R / ESTILO K 7099 WAGON R GAS REAR 673 AM-G07714 DAMPER WITH BK ( GAS) FRONT 1885 G07713 DAMPER WITHOUT BK ( GAS) FRONT 1600 K 7566 WAGON R / ESTILO ASSY FRONT 2491 AM-G07715 WAGON R ASSY ( GAS) FRONT 2518 WAGON R K K07331 / 30 M/Wagon R K Series Assy LH / RH (GAS) FRONT 2716 K07323 / 24 M/Wagon R K Series Damper RH/ LH (GAS) FRONT 1528 K07328 Wagon R GAS K Series REAR 853 G 105046 BUSH KIT FRONT 313 ALTO K 7098 ALTO GAS REAR -

Printmgr File

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on August 2, 2013 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ⌧ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal year ended March 31, 2013 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report Commission file number: 001-32294 TATA MOTORS LIMITED (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Not applicable (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Bombay House 24, Homi Mody Street Republic of India Mumbai 400 001, India (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (Address of principal executive offices) H.K. Sethna Tel.: +91 22 6665 7219 Facsimile: +91 22 6665 7260 Address: Bombay House 24, Homi Mody Street Mumbai 400 001, India (Name, telephone, facsimile number and address of company contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Ordinary Shares, par value Rs.2 per share * The New York Stock Exchange, Inc Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. -

TATA MOTORS with the Industry’S Competitor & CUSTOMER SATISFACTION SURVEY

Project on Comparative study of TATA MOTORS with the Industry’s Competitor & CUSTOMER SATISFACTION SURVEY Exceutive Summary This project is on Comparative study of TATA MOTORS with the Industry’s Competitor & CUSTOMER SATISFACTION SURVEY based on market performance and on customer survey. The main objectives of the project are: Market performance in automobile industry Market position. Economic and the industry environment Cost saving initiatives Awareness regarding the facilities provided by Tata Motors. Overall opinion about Tata Motors. Satisfaction amongst the customers of Tata Motors For this project customer research was carried out at various area of Thane District of Maharashtra. I learnt analysis of Market performance by Tata Motors and to find different aspects for compare the standing vis-á-vis industry and customer‘s perception about TATA Motors. THE REPORTS IS DIVIDED INTO VARIOUS SECTIONS 1. Company Overview: This part describes the company profile. This part recognizes the achievements and rewards the company has achieved, it also gives little insights into what company offers to the Corporate and the Consumers. This section also describes the kind of technology used. 2. Company Profile This section gives the information about the company. It includes the company history which depicts the company from the period of foundation. This section also products of the company producing by the company. Competitors of company: The company‘s competitors are finding and study the business during the financial years FINDINGS: A detailed analysis of the company shows that the company has had a strong fundamental as well as a strong market performance over the years. Given the economic and the industry environment (improving outlook for the CV industry) TATA Motors would be a key beneficiary. -

Price List- 4W

PRICE LIST- 4W Price Revision New Introduction With Effect From 01 Mar 2019 LIGHTING S.no HSN Item Code SAP Code Description MRP Std. Pkg MOQ MSZ 800 CC CAR Head Lamp 1 85122010 031-HLA- - 61001695 H/L ASSY 800 CC T -1 330 16 16 2 85122010 031-HLA-MN 61005810 HL ASSY 800CC CAR MFR P43 W/O 'P' 517 24 12 3 85122010 031-HLA-PN - 61001696 H/L ASSY. N/M MARUTI 800CC CAR (P43T) 356 16 8 4 85122010 030-HLU-T - 61001668 H/L UNIT 800CC P45T WT THERMOCOL 198 24 12 5 85122010 030-HLU-MN - 61001663 REF. UNIT M 800CC CAR MFR P43T W/O PARKI 378 24 12 6 85122010 030-HLU-N - 61001665 R/UNIT MARUTI 800CC CAR(P43T) 201 24 12 7 85122010 030-HLU-PA - 61001666 REF. UNIT M.CAR 800CC WITH PARKING 208 24 12 8 85122010 030-HLU-PNA- 61001667 REFLECTOR UNIT M 800CC CAR P43T WITH PAR 208 24 12 9 85122010 029-HLU-L - 61001637 H/L UNIT CAR 800CC Y5A LH 411 18 18 10 85122010 029-HLU-R - 61001642 H/L UNIT CAR 800CC Y5A RH 411 18 18 11 85122010 029-HLU-LL - 61001638 H/L UNIT CAR 800CC Y5A LASER LH 314 18 9 12 85122010 029-HLU-LR - 61001639 H/L UNIT CAR 800CC Y5A LASER RH 314 18 9 13 85122010 029-HLU-NWM-BK-L 61006171 H/L UNIT 800CC CAR T-3 WT BK HSG LH 914 12 12 14 85122010 029-HLU-NWM-BK-R 61006172 H/L UNIT CAR 800CC T3 WT BK HSG RH 914 12 12 15 85122010 029-HLU-NWM-L 61001640 H/L UNIT 800CC T-3 MFR LH 903 12 12 16 85122010 029-HLU-NWM-R 61001641 H/L UNIT 800CC T-3 MFR RH 903 12 12 17 85122010 030-HLU-MNP- 61001664 H/L UNIT 800CC MFR P43T WT PARKING 390 24 12 18 85122010 031-HLA-MNP 61005811 H/L ASSY 800CC N/M MFR P43T WT PARKING 529 24 12 Tail Lamps 19 85122010 031-RCU-L