Benjamin Trott: Miniature Painter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions As of August 1, 2002 Note to the Reader The works of art illustrated in color in the preceding pages represent a selection of the objects in the exhibition Gifts in Honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Checklist that follows includes all of the Museum’s anniversary acquisitions, not just those in the exhibition. The Checklist has been organized by geography (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) and within each continent by broad category (Costume and Textiles; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; Sculpture). Within each category, works of art are listed chronologically. An asterisk indicates that an object is illustrated in black and white in the Checklist. Page references are to color plates. For gifts of a collection numbering more than forty objects, an overview of the contents of the collection is provided in lieu of information about each individual object. Certain gifts have been the subject of separate exhibitions with their own catalogues. In such instances, the reader is referred to the section For Further Reading. Africa | Sculpture AFRICA ASIA Floral, Leaf, Crane, and Turtle Roundels Vests (2) Colonel Stephen McCormick’s continued generosity to Plain-weave cotton with tsutsugaki (rice-paste Plain-weave cotton with cotton sashiko (darning the Museum in the form of the gift of an impressive 1 Sculpture Costume and Textiles resist), 57 x 54 inches (120.7 x 115.6 cm) stitches) (2000-113-17), 30 ⁄4 x 24 inches (77.5 x group of forty-one Korean and Chinese objects is espe- 2000-113-9 61 cm); plain-weave shifu (cotton warp and paper cially remarkable for the variety and depth it offers as a 1 1. -

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Hart Autograph Collection, 1731-1918, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Hart Autograph Collection, 1731-1918, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Josefson Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 February 20 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Charles Henry Hart autograph collection, 1731-1918............................... 4 Series 2: Unprocessed Addition, 1826-1892 and undated..................................... 18 Charles Henry Hart autograph collection AAA.hartchar Collection -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1946, Volume 41, Issue No. 4

MHRYMnD CWAQAZIU^j MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE DECEMBER • 1946 t. IN 1900 Hutzler Brothers Co. annexed the building at 210 N. Howard Street. Most of the additional space was used for the expansion of existing de- partments, but a new shoe shop was installed on the third floor. It is interesting to note that the shoe department has now returned to its original location ... in a greatly expanded form. HUTZLER BPOTHERSe N\S/Vsc5S8M-lW MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE A Quarterly Volume XLI DECEMBER, 1946 Number 4 BALTIMORE AND THE CRISIS OF 1861 Introduction by CHARLES MCHENRY HOWARD » HE following letters, copies of letters, and other documents are from the papers of General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble (b. 1805, d. 1888). They are confined to a brief period of great excitement in Baltimore, viz, after the riot of April 19, 1861, when Federal troops were attacked by the mob while being marched through the City streets, up to May 13th of that year, when General Butler, with a large body of troops occupied Federal Hill, after which Baltimore was substantially under control of the 1 Some months before his death in 1942 the late Charles McHenry Howard (a grandson of Charles Howard, president of the Board of Police in 1861) placed the papers here printed in the Editor's hands for examination, and offered to write an introduction if the Committee on Publications found them acceptable for the Magazine. Owing to the extraordinary events related and the revelation of an episode unknown in Baltimore history, Mr. Howard's proposal was promptly accepted. -

Papers of the American Slave Trade

Cover: Slaver taking captives. Illustration from the Mary Evans Picture Library. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Papers of the American Slave Trade Series A: Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society Part 2: Selected Collections Editorial Adviser Jay Coughtry Associate Editor Martin Schipper Inventories Prepared by Rick Stattler A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society [microfilm] / editorial adviser, Jay Coughtry. microfilm reels ; 35 mm.(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Martin P. Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. Contents: pt. 1. Brown family collectionspt. 2. Selected collections. ISBN 1-55655-650-0 (pt. 1).ISBN 1-55655-651-9 (pt. 2) 1. Slave-tradeRhode IslandHistorySources. 2. Slave-trade United StatesHistorySources. 3. Rhode IslandCommerce HistorySources. 4. Brown familyManuscripts. I. Coughtry, Jay. II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. Rhode Island Historical Society. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. VI. Series. [E445.R4] 380.14409745dc21 97-46700 -

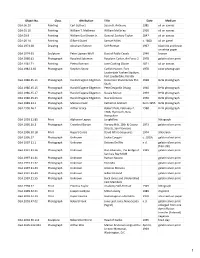

1 Object No. Class. Attribution Title Date Medium CGA.00.10 Painting

Object No. Class. Attribution Title Date Medium CGA.00.10 Painting Carl Gutherz Susan B. Anthony 1985 oil on canvas CGA.01.10 Painting William T. Mathews William McKinley 1900 oil on canvas CGA.03.9 Painting William Garl Brown Jr. General Zachary Taylor 1847 oil on canvas CGA.09.14 Painting Gilbert Stuart Samuel Miles c. 1800 oil on panel CGA.1974.28 Drawing Abraham Rattner Self-Portrait 1967 black ink and brush on white paper CGA.1974.63 Sculpture Peter Lipman-Wulf Bust of Pablo Casals 1946 bronze CGA.1980.61 Photograph Rosalind Solomon Rosalynn Carter, Air Force 2 1978 gelatin silver print CGA.1981.71 Painting Pietro Bonnani Jane Cocking Glover 1821 oil on canvas CGA.1982.3.60 Photograph Stephen Shore Catfish Hunter, Fort 1978 color photograph Lauderdale Yankee Stadium, Fort Lauderdale, Florida CGA.1986.45.11 Photograph Harold Eugene Edgerton Densmore Shute Bends The 1938 B+W photograph Shaft CGA.1986.45.15 Photograph Harold Eugene Edgerton Pete Desjardin Diving 1940 B+W photograph CGA.1986.45.17 Photograph Harold Eugene Edgerton Gussie Moran 1949 B+W photograph CGA.1986.45.23 Photograph Harold Eugene Edgerton Gus Solomons 1960 B+W photograph CGA.1989.13.1 Photograph Mariana Cook Katharine Graham born 1955 B+W photograph CGA.1990.16.2 Photograph Arthur Grace Robert Dole, February 2, 1988 B+W photograph 1988, Plymouth, New Hampshire CGA.1993.11.85 Print Alphonse Legros Longfellow lithograph CGA.1995.10.3 Photograph Crawford Barton Harvey Milk, 18th & Castro 1973 gelatin silver print Streets, San Francisco CGA.1996.50.18 Print Rupert Garcia David Alfaro Sequeiros 1974 silkscreen CGA.1996.57 Photograph Unknown Jackie Coogan c. -

Landon·Genealogy

LANDON·GENEALOGY LANDON GENEALOGY THE FRENCH: AND ENGLISH HOME AND ANCESTRY WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF THE DESCENDANTS OF JAMES AND MARY VAILL. LANDON IN AMERICA PART II BOARDMAN GENEALOGY THE ENGLISH HOME AND ANCESTRY OF SAMUEL BOREMAN AND THOMAS BOREMAN, NOW CALLED BOARDMAN' WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF THEIR DESCENDANTS IN AMERICA Bv JAMES ORVILLE LANDON NEW YORK, N. Y. SOUTH HERO, VT. CLARK BOARDMAN CO., LTD. 1928 FOREWORD Our father, the author and compiler of this work, died suddenly July 7, 1927, in his 87th year. He had, however, completed his task the March previous, and the manuscript was ready for the printer. _ Since his retirement over twenty years ago he had devoted most of his time to the collecting and compilation of these records, which was to him of such great interest and most decidedly a labor of love. This research work kept his mind most active, and up to the day of his death he was as keen and bright and as interested in all things as the man of fifty. We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance given him in transcribing the manuscript by Emma Jeffrey Tucker of Everett, Massachusetts. We also express our great appreciation to Colonel Thomas Durland Landon and to Mr. Clark Boardman, and to the others who assisted in the underwriting of the expense of this publica tion, without whose help these records might not have been pub lished and preserved in permanent form for future generations. KATE HUNTINGTON LANDON LUCY HIN-CKLEY LANDON WOOD July 15, 1928 iii IMITATE OUR FATHERS "Honor to ~e memory of our fathers: May the turf lie gently on their sacred graves: but let us not in word only, but in deeds also, testify our reverence for their names. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

I Wonder. . . I Notice

I notice. P a c i f i c O c e a n Gulf of CANADA St. Lawrence Washington Delaware Montana and Hudson Oregon Lake Canal North Dakota Minnesota Superior Maine Yellowstone Idaho NP Vermont Lake Huron New Hampshire Wisconsin rio Wyoming South Dakota Onta Lake Massachusetts New York Great Salt Lake Michigan Nevada Lake Michigan ie Er ke Rhode Nebraska Iowa La Island Utah M Pennsylvania Yosemite NP i s Connecticut s o Ohio u Colorado r New Jersey i R Illinois Indiana iv r Washington D.C. e er Delaware iv Kansas R West io California h Missouri O Virginia Virginia Maryland Grand Canyon NP Kentucky Arizona North Carolina Oklahoma Tennessee New r Arkansas e v i R Mexico i South p p i Carolina s s i s s i Georgia M Alabama Union States Texas Mississippi Confederate States Louisiana A t l a n t i c Border states that O c e a n stayed in the Union Florida Other states G u l f MEXICO National Parks o f Delaware and M e x i c o Hudson Canal, 1866 John Wesley Jarvis (1780–1840) Philip Hone, 1809 Oil on wood panel, 34 x 26¾ in. (86.4 x 67.9 cm) Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd 1986.84 I wonder. 19th-Century American Object Information Sheet 8th Grade 1 Philip Hone Lakes to the Hudson River. This new 19TH-CENTURY AMERICA waterway greatly decreased the cost of shipping. IETY C O S Politically, Hone was influential AL Your Historic Compass: C in the organization of the Whig Whig party: The Whig party first took shape in 1834. -

Early American Portrait Painters in Miniature

E A R LY A M E RIC A N PO RT RA IT PA IN T E RS IN M IN IA T U RE TH E O D O RE BO L TO N N EW YORK O FREDERIC FAIRCHILD SHERMAN MCMXXI LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS MA L B O NE , EDWARD Ch arles Harris Fron tispiccc Ni cholas Bowm an FACI NG PA GE COPLEY, JOHN SINGLETON Self Portrai t VA N AM E s DYCK, J J ames Lyon H E N Y . R BROWN , J President Buch an an M DUNLAP, WILLIA President Tyler F ULTON , ROBERT S amuel Beach DUVAL, AMBROSE G . a r OV . Wm . C . C Cl ibo ne BO U N E TH E A U . , HENRY B r a Hen y M . Manig ult A R BAKER, GEORGE . , J . Andrew J ackson BIRCH , WILLIAM George Washin gton PE TTI CO LAs . , E A George Washington D R . M THORNTON , WILLIA George Washington RAMAGE, JOHN George Washin gton CLARK, ALVAN B arn a b as Cl ark iii FA CI NO PAG E GIMBREDE , THOMAS Mr . Schley BRIDPORT, H . C aroline Dugan INMAN , HENRY Por trait of a Lady JARVIS , JOHN WESLEY Miss J arvis ALLSTON , WASHINGTON i . Pra C apta n A H . y TROTT, BENJAMIN Lewis Adams P EALE , JAMES V n N r . a M s John P . ess M ANDRE , AJOR JOHN M argaret Shippen STAIGG M . , RICHARD John Lothrop Motley P ELHAM, HENRY Jon a th an Cl ark SAVAGE , EDWARD Self Por trait F IELD, ROB ERT George Washington a ar i M . -

Portrait Miniatures in the New Republic

he stunning events of July 1804 were almost unfath- omable for the citizens of the new American republic. One Founding Father had fatally wounded another. TAlexander Hamilton was dead and Aaron Burr would be indicted for murder. The duel and its aftermath marked a turning point in American culture. Five days before the Burr-Hamilton duel, Edward Greene Malbone arrived for a week’s stay in New York. Considered the Portrait finest miniaturist in the United States, Malbone was attractive, popular, already exceedingly successful, and only twenty-six miniatures years old. As Hamilton’s massive funeral snaked up Broadway on July 14, he was meeting twenty-five year-old Anson Dick- Left to right, from facing page, bottom: in the New inson for the first time. A fledgling artist, Dickinson had com- Fig. 1. Anson Dickinson [1779– missioned Malbone to paint his miniature, hoping to learn by 1852] by Edward Greene Malbone Republic (1777–1807), 1804. Watercolor on 1 watching the more experienced artist at work (Fig. 1). So ab- ivory, 2 ½ by 1 7⁄8 inches. Stamford sorbed was Malbone in the painting “that he neither paused Historical Society, Connecticut, 2 Cruikshank Bequest. himself to view the pageant nor suffered his sitter to do so.” Fig 2. John Francis [1763–1796] by Around the corner on Wall Street, twenty-five-year-old Malbone, 1795. Signed and dated Joseph Wood and twenty-three-year-old John Wesley Jarvis had “Malbone 1795” at center right. recently formed an artistic partnership. All four artists, soon to Watercolor on ivory, 2 13⁄16 by 2 1⁄8 inches. -

This Page Was Intentionally Removed Due to a Research Restriction on All Corcoran Gallery of Art Development and Membership Records

This page was intentionally removed due to a research restriction on all Corcoran Gallery of Art Development and Membership records. Please contact the Public Services and Instruction Librarian with any questions. Jh (ft^1—'-®L d'. Consideration of Mr. and Mrs. Maxwell Oxman's offer of the unrestricted gift of a marble sculpture Warriors Head by Josef Erhardy through the Friends of the Corcoran. Consideration of Mr. Bruce Moore's offer of the unrestricted gift of a drawing Sleeping Tiger by himself. o u f. Conisderation of Mr. William E. Share's offer of the unrestricted gift of a sculpture Head of a Woman by Ossip Zadkine. Y g. Consideration of Mrs. Armistead Peter, Ill's offer of the unrestricted gift of a pastel Willows, Longpr^f, France by Walter Griffin. - h. Tentative consideration of Mr. Monte Appel's offer of the unrestricted gift of a painting Asa Clapp by John Wesley Jarvis. CONSIDERATION OF PURCHASE Consideration of the purchase of a painting The Angler (Charles Lanman) by i- William Hubard at approximately $ ,000 from Mr. George Katsafouros. | j. Consideration of the purchase of a painting Study of William Williamson by VvA" j Samuel F. B. Morse at $325.00 from Mr. N. Valdemar Hilbert. vj? k. Consideration of the purchase of a painting Woman in White by Gari Melchers ^S''' at $1,500 from Mrs. M. Veldman-Halff. \j 1. Consideration of the purchase of a drawing Man on Horseback by Frederic (j Remington at $400 from the Eberstadt Gallery. Preliminary discussion of the possible purchase of a painting The Captured Liberators by Winslow Homer at $40,000 from the Eberstadt Gallery. -

NEH Coversheet: GRANT10749845

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/preservation/sustaining-cultural-heritage-collections for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Improving Environmental Conditions to Preserve Collections Institution: Litchfield Historical Society Project Director: Julie Leone Grant Program: Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 411, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8570 F 202.606.8639 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Description of Project and its Significance The Litchfield Historical Society (LHS) seeks a Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections Implementation Grant of $399,412 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to execute specific recommendations made by an interdisciplinary team of experts consisting of an architect, engineer and museum conservator. The Society hired these consultants with funds provided by a 2009 NEH Sustaining Cultural Heritage Planning Grant.