AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary Aggregate Spending (GDP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untangling Misconceptions About Inflation and Predicting Its Path After COVID-19

GLOBAL EQUITY Investment Management active.williamblair.com Low-Inflation Nation: Untangling Misconceptions About Inflation and Predicting Its Path After COVID-19 Investors are preoccupied with inflation for good reason: It affects interest October 2020 rates, public-equity valuations, private-equity access to capital and, Global Strategist ultimately, stock-price multiples. Yet confusion about inflation assumptions Olga Bitel, Partner and forecasts could lead investors astray. In this report, Olga Bitel, partner, global strategist, discusses inflation and the factors that influence it. She explains why both aggregate demand growth and inflation may be higher over the next decade than in the 2010s, with major implications for asset allocation. Introduction Inflation is a subject that can spur extreme opinions, often without evidence to support them. Misconceptions about inflation abound, particularly as the European Central Bank (ECB), U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed), and others have pursued unconventional monetary policies. Some investors have blamed central banks for slow economic growth between 2008 and 2019. Others predicted a surge in inflation that never materialized. D.J. Neiman, CFA, Investors are preoccupied with inflation for good reason: It affects interest rates, public- Partner equity valuations, private-equity access to capital and, ultimately, stock-price multiples. The recent policy change announced by U.S. Fed Chairman Jerome H. Powell to allow inflation to run at an average rate of 2% over time, rather than setting that figure as a strict threshold, will fuel the debate about central-bank policy, inflation, and growth. Yet confusion about inflation assumptions and forecasts could lead investors astray. Olga Bitel, global strategist at William Blair, developed this report to clarify the definition of inflation and the factors that influence it. -

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP)

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP): The sum of all spending from four sectors of the economy. GDP = C+I+G+Xn 2. Aggregate Income (AI) :The sum of all income earned by suppliers of resources in the economy. AI=GDP 3. Nominal GDP: the value of current production at the current prices 4. Real GDP: the value of current production, but using prices from a fixed point in time 5. Base year: the year that serves as a reference point for constructing a price index and comparing real values over time. 6. Price index: a measure of the average level of prices in a market basket for a given year, when compared to the prices in a reference (or base) year. 7. Market Basket: a collection of goods and services used to represent what is consumed in the economy 8. GDP price deflator: the price index that measures the average price level of the goods and services that make up GDP. 9. Real rate of interest: the percentage increase in purchasing power that a borrower pays a lender. 10. Expected (anticipated) inflation: the inflation expected in a future time period. This expected inflation is added to the real interest rate to compensate for lost purchasing power. 11. Nominal rate of interest: the percentage increase in money that the borrower pays the lender and is equal to the real rate plus the expected inflation. 12. Business cycle: the periodic rise and fall (in four phases) of economic activity 13. Expansion: a period where real GDP is growing. 14. Peak: the top of a business cycle where an expansion has ended. -

Has the US Finance Industry Become Less Efficient? on the Theory and Measurement of Financial Intermediation†

American Economic Review 2015, 105(4): 1408–1438 http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120578 Has the US Finance Industry Become Less Efficient? On the Theory and Measurement of Financial Intermediation† By Thomas Philippon * A quantitative investigation of financial intermediation in the United States over the past 130 years yields the following results: i the finance industry’s share of gross domestic product GDP is high( ) in the 1920s, low in the 1960s, and high again after 1980( ; )ii most of these variations can be explained by corresponding changes( ) in the quantity of intermediated assets equity, household and corporate debt, liquidity ; iii intermediation( has constant returns to scale and an annual cost) of( 1.5–2) percent of intermediated assets; iv secular changes in the characteristics of firms and households are( )quantita- tively important. JEL D24, E44, G21, G32, N22 ( ) This paper is concerned with the theory and measurement of financial interme- diation. The role of the finance industry is to produce, trade, and settle financial contracts that can be used to pool funds, share risks, transfer resources, produce information, and provide incentives. Financial intermediaries are compensated for providing these services. The income received by these intermediaries measures the aggregate cost of financial intermediation. This income is the sum of all spreads and fees paid by nonfinancial agents to financial intermediaries and it is also the sum of all profits and wages in the finance industry. This cost of financial intermediation affects the user cost of external finance for firms who issue debt and equity, and the costs for households who borrow or use asset management services. -

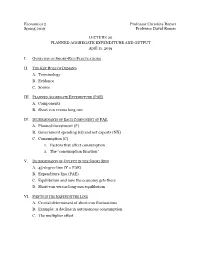

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of . -

The Macroeconomic Implications of Consumption: State-Of-Art and Prospects for the Heterodox Future Research

The macroeconomic implications of consumption: state-of-art and prospects for the heterodox future research Lídia Brochier1 and Antonio Carlos Macedo e Silva2 Abstract The recent US economic scenario has motivated a series of heterodox papers concerned with household indebtedness and consumption. Though discussing autonomous consumption, most of the theoretical papers rely on private investment-led growth models. An alternative approach is the so-called Sraffian supermultipler model, which treats long-run investment as induced, allowing for the possibility that other final demand components – including consumption – may lead long-run growth. We suggest that the dialogue between these approaches is not only possible but may prove to be quite fruitful. Keywords: Consumption, household debt, growth theories, autonomous expenditure. JEL classification: B59, E12, E21. 1 PhD Student, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil. [email protected] 2 Professor at University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil. [email protected] 1 1 Introduction Following Keynes’ famous dictum on investment as the “causa causans” of output and employment levels, macroeconomic literature has tended to depict personal consumption as a well-behaved and rather uninteresting aggregate demand component.3 To be sure, consumption is much less volatile than investment. Does it really mean it is less important? For many Keynesian economists, the answer is – or at least was, until recently – probably positive. At any rate, the American experience has at least demonstrated that consumption is important, and not only because it usually represents more than 60% of GDP. After all, in the U.S., the very ratio between consumption and GDP has been increasing since the 1980s, in spite of the stagnant real labor income and the growing income inequality. -

Chapter 4.Pmd

Chapter4 Determination of Income and Employment We have so far talked about the national income, price level, rate of interest etc. in an ad hoc manner – without investigating the forces that govern their values. The basic objective of macroeconomics is to develop theoretical tools, called models, capable of describing the processes which determine the values of these variables. Specifically, the models attempt to provide theoretical explanation to questions such as what causes periods of slow growth or recessions in the economy, or increment in the price level, or a rise in unemployment. It is difficult to account for all the variables at the same time. Thus, when we concentrate on the determination of a particular variable, we must hold the values of all other variables constant. This is a stylisation typical of almost any theoretical exercise and is called the assumption of ceteris paribus, which literally means ‘other things remaining equal’. You can think of the procedure as follows – in order to solve for the values of two variables x and y from two equations, we solve for one variable, say x, in terms of y from one equation first, and then substitute this value into the other equation to obtain the complete solution. We apply the same method in the analysis of the macroeconomic system. In this chapter we deal with the determination of National Income under the assumption of fixed price of final goods and constant rate of interest in the economy. The theoretical model used in this chapter is based on the theory given by John Maynard Keynes. -

GDP As a Measure of Economic Well-Being

Hutchins Center Working Paper #43 August 2018 GDP as a Measure of Economic Well-being Karen Dynan Harvard University Peterson Institute for International Economics Louise Sheiner Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, The Brookings Institution The authors thank Katharine Abraham, Ana Aizcorbe, Martin Baily, Barry Bosworth, David Byrne, Richard Cooper, Carol Corrado, Diane Coyle, Abe Dunn, Marty Feldstein, Martin Fleming, Ted Gayer, Greg Ip, Billy Jack, Ben Jones, Chad Jones, Dale Jorgenson, Greg Mankiw, Dylan Rassier, Marshall Reinsdorf, Matthew Shapiro, Dan Sichel, Jim Stock, Hal Varian, David Wessel, Cliff Winston, and participants at the Hutchins Center authors’ conference for helpful comments and discussion. They are grateful to Sage Belz, Michael Ng, and Finn Schuele for excellent research assistance. The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. Neither is currently an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article. ________________________________________________________________________ THIS PAPER IS ONLINE AT https://www.brookings.edu/research/gdp-as-a- measure-of-economic-well-being ABSTRACT The sense that recent technological advances have yielded considerable benefits for everyday life, as well as disappointment over measured productivity and output growth in recent years, have spurred widespread concerns about whether our statistical systems are capturing these improvements (see, for example, Feldstein, 2017). While concerns about measurement are not at all new to the statistical community, more people are now entering the discussion and more economists are looking to do research that can help support the statistical agencies. While this new attention is welcome, economists and others who engage in this conversation do not always start on the same page. -

The Sraffian Supermultiplier and the Stylized Facts

Texto para Discussão 005 | 2019 Discussion Paper 005 | 2019 Stagnation and unnaturally low interest rates: a simple critique of the amended New Consensus and the Sraffian supermultiplier alternative Franklin Serrano Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Ricardo Summa Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Vivian Garrido Moreira Universidade Estadual do Centro Oeste - UNICENTRO This paper can be downloaded without charge from http://www.ie.ufrj.br/index.php/index-publicacoes/textos-para-discussao Stagnation and unnaturally low interest rates: a simple critique of the amended New Consensus and the Sraffian supermultiplier alternative1 March. 2019 Franklin Serrano Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Ricardo Summa Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Vivian Garrido Moreira Universidade Estadual do Centro Oeste – UNICENTRO Abstract This paper argues that the amended versions (financial wedge and secular stagnation) of the simple pragmatic New Consensus model are as open to theretical criticism as the original one. We show that: (1) the real natural rate of interest is unlikely to be negative and (2) it (inconsistently) depends on the neoclassical investment function drawn at a position of full employment, in a model which the economy is demand constrained; (3) both investment and full employment saving are induced by the trend of demand in the longer run and this challenges the usefulness of the notion of a natural or neutral rate of interest, which (4) are also subject to the sraffian capital critique. This is then constrasted to an alternative simple Sraffian Supermultiplier model in which the interest rate and the financial wedge are distributive instead of allocative variables, and there is no natural rate of interest since in the longer run there is no trade-off between consumption and investment and also no full employment of labor. -

Joana David Avritzer Debt-Led Growth and Its Financial Fragility: An

Joana David Avritzer Debt-led growth and its financial fragility: an investigation into the dynamics of a supermultiplier model March 2021 Working Paper 06/2021 Department of Economics The New School for Social Research The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the New School for Social Research. © 2021 by Joana David Avritzer. All rights reserved. Short sections of text may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit is given to the source. Debt-led growth and its financial fragility: an investigation into the dynamics of a supermultiplier model Joana David Avritzer1 This paper discusses the financial sustainability of demand-led growth models. We assume a supermultiplier growth model in which household consumption is the autonomous component of demand that drives growth and discuss the financial sustainability of such dynamics of growth from the perspective of the working households. We show that for positive rates of growth the model converges to an equilibrium where worker households are accumulating debt and not wealth. We also show that when the economy is growing at a rate that is positive, and between 2% and 4.4%, the dynamics of the model also implies that households will not be able to service their debt at the point of full long run equilibrium. We then conclude that this household debt-financed consumption pattern of economic growth generates an internal dynamic that leads to financial instability. Keywords: household debt dynamics, debt-financed consumption, growth and financial fragility; JEL Classification: E11, E12, E21, O41. 1 Connecticut College and IRID-UFRJ, email: [email protected]; 1. -

Measuring Gdp and Economic Growth

MEASURING GDP Objectives AND ECONOMIC CHAPTER GROWTH 20 After studying this chapter, you will able to Define GDP and use the circular flow model to explain why GDP equals aggregate expenditure and aggregate income Explain the two ways of measuring GDP Explain how we measure real GDP and the GDP deflator Explain how we use real GDP to measure economic growth and describe the limitations of our measure © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 An Economic Barometer Gross Domestic Product GDP Defined What exactly is GDP GDP or gross domestic product, is the market value of How do we use it to tell us whether our economy is in a all final goods and services produced in a country in a recession or how rapidly our economy is expanding? given time period. How do we take the effects of inflation out of GDP to This definition has four parts: compare economic well-being over time Market value And how to we compare economic well-being across Final goods and services counties? Produced within a country In a given time period © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 Gross Domestic Product Gross Domestic Product Final goods and services Market value GDP is the value of the final goods and services produced. GDP is a market value—goods and services are valued at their market prices. A final good (or service), is an item bought by its final user during a specified time period. To add apples and oranges, computers and popcorn, we add the market values so we have a total value of output A final good contrasts with an intermediate good, which is in dollars. -

The Way Brands Work: Consumers' Understanding of the Creation and Usage of Brands

The Way Brands Work: Consumers' understanding of the creation and usage of brands Bertilsson, Jon 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bertilsson, J. (2009). The Way Brands Work: Consumers' understanding of the creation and usage of brands. Lund Business Press. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 The way brands work Consumers’ understanding of the creation and usage of brands Jon Bertilsson Lund Institute of Economic Research School of Economics and Management Lund Business Press Lund Studies in Economics and Management 114 Lund Business Press Lund Institute of Economic Research P.O.