The HOPE METHOD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

John & Yoko / Plastic Ono Band with Elephant's Memory and Invisible

John & Yoko Some Time In New York City mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Some Time In New York City Country: UK Released: 1972 Style: Rock & Roll, Art Rock, Noise, Avantgarde, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1627 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1266 mb WMA version RAR size: 1927 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 741 Other Formats: MIDI MPC VQF VOX DMF APE TTA Tracklist Hide Credits Sometime In New York City Woman Is The Nigger Of The –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants A1 World Memory And Invisible Strings Written-By – Lennon-Ono* –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants Sisters O Sisters A2 Memory And Invisible Strings Written-By – Ono* –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants Attica State A3 Memory And Invisible Strings Written-By – Lennon-Ono* Born In A Prison –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants A4 Piano – John La BoscaWritten-By Memory And Invisible Strings – Ono* –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants New York City A5 Memory And Invisible Strings Written-By – Lennon* –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants Sunday Bloody Sunday B1 Memory And Invisible Strings Written-By – Lennon-Ono* –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants The Luck Of The Irish B2 Memory And Invisible Strings Written-By – Lennon-Ono* John Sinclair –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants B3 Slide Guitar – John*Written-By – Memory And Invisible Strings Lennon* –John & Yoko* / Plastic Ono Band* With Elephants Angela B4 Memory And Invisible Strings Written-By – Lennon-Ono* –John -

Environment/Will

ENVIRONMENT IS STRONGER THAN WILL - R. Buckminster Fuller A Comprehensivist’s Approach to Structuring Environments for Success 12° of Freedom Chapter IV: Environment Is Stronger Than Will Chapter IV: Environment Is Stronger Than Will: A Comprehensivist’s Approach to Structuring Environments for Success, addresses the questions: How is this discipline applied in an addictions treatment program, in prison or in any treatment setting? How does one establish a Total Learning Environment™ in prison? What results can be expected from a treatment approach based in Synergetics? The purpose, methods and results of the TLE™ are described from their origin in the Network Program, through Shock Incarceration, the Willard Drug Treatment Campus, and related programs in other jurisdictions. Results of the longitudinal research about Shock Incarceration are presented to demonstrate that this model produces positive results when offenders are compared with similar cohorts. Several factors, including cost of care, educational development, community services, after care, recidivism and success rates post-release, are offered as evidence of the model’s effective design and operations. A Comprehensivist’s Approach To Treatment 299 Specialization Leads To Extinction 302 “From Plantations, To Projects, to Prisons” 307 Environments For Change In Prisons 316 Treatment Models 320 A Wholistic Approach 326 “Keep Hope Alive” 345 Gangs To Graduates 352 From Compliance To Autonomy 370 Graduation From Prison 382 Results Unpredicted By Behavior of Individual Components Alone 384 AfterShock and After Care 400 Footnotes 403 Staff Training Schedule 412 298 Cheryl Lirette Clark 12° of Freedom Synergetics and the 12 Steps to Recovery ENVIRONMENT IS STRONGER THAN WILL A Comprehensivist’s Approach To Treatment “I would never try to reform man —that’s much too difficult. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

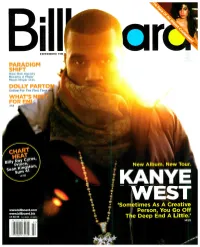

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

Click on This Link

The Australian Songwriter Issue 139, February 2019 First published 1979 Celebrating 40 Years (1979 to 2019) The Magazine of The Australian Songwriters Association Inc. In This Edition: On the Cover of the ASA: Iva Davies, 2018 Inductee Into The Australian Songwriters Hall Of Fame Chairman’s Message Editor’s Message Iva Davies: 2018 Inductee Into The Australian Songwriters Hall Of Fame More 2018 National Songwriting Awards Photos Lola Brinton: 2018 Winner Of The Rudy Brandsma Award Wax Lyrical Roundup Carole Beck: Tamworth and Parkes NSW Festivals 2019 Wendy J Barnes: 2018 ASA Regional Co-Ordinator Of The Year Sponsors Profiles ASA Member Profile: Kylie Adams-Collier Members News and Information ASA Members CD Releases Mark Cawley’s Monthly Songwriting Blog The Load Out Official Sponsors of the Australian Songwriting Contest About Us: o Aims of the ASA o History of the Association o Contact Us o Patron o Life Members o Directors o Regional Co-Ordinators o Webmaster o 2018 APRA/ASA Songwriter of the Year o 2018 Rudy Brandsma Award Winner o 2018 PPCA Live Performance Award Winner o Australian Songwriters Hall of Fame (2004 to 2018) o Lifetime Achievement Award o 2018 Australian Songwriting Contest Category Winners o Songwriters of the Year and Rudy Brandsma Award (1983 to 2018) Chairman’s Message Your Board is back in full swing already as we prepare for our 2019 Australian Songwriting Contest. The ASA has two Major Sponsors, being APRA/AMCOS and WESTS ASHFIELD. If you are a Songwriter, you should know by now that you need to join APRA, not only to support them, but also to register your songs and get any royalties that you are entitled to. -

ピーター・バラカン 2013 年 6 月 1 日放送 Sun Ra 特

ウィークエンド サンシャイン PLAYLIST ARCHIVE DJ:ピーター・バラカン 2013 年 6 月 1 日放送 Sun Ra 特集 ゲスト:湯浅 学 01. We Travel The Space Ways / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra // Greatest Hits: Easy Listening For Intergalatic Travel 02. Saturn / Sun Ra & His Solar Arkestra // Visits Planet Earth Interstellar Low Ways 03. Dig This Boogie / Wynonie Harris with Jumpin' Jimmy Jackson Band // The Eternal Myth Revealed, Vol.1 04. Message to Earth Man / Yochanan, Sun Ra And The Arkestra // The Singles 05. MU / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra / Atlantis 06. The Design-Cosmos II / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra // My Brother The Wind Volume II 07. The Perfect Man / Sun Ra And His Astro Galactic Infinity Arkestra // The Singles 08. Gods of The Thunder Realm / Sun Ra And His Arkestra // Live At Montreux 09. Rocket#9 / Sun Ra // Space Is The Place 10. Dancing In The Sun / Sun Ra & His Solar Arkestra // The Heliocentric Worlds Of Sun Ra Vol.1 11. Take The A Train / Sun Ra Arkestra // Sunrise In Different Dimensions 12. The Old Man Of The Mountain / Phil Alvin // Phil Alvin Un "Sung Stories" 13. Love In Outer Space / Sun Ra // Purple Night 14. Lanquidity / Sun Ra // Lanquidity 2013 年 6 月 8 日放送 01. You're My Kind Of Climate (Party Mix) / Rip Rig & Panic // Methods Of Dance Volume 2 02. Bold As Love / Jimi Hendrix // The Jimi Hendrix Experience: Box Set 03. Who'll Stop The Rain / John Fogerty with Bob Seger // Wrote A Song For Everyone 04. Fortunate Son / John Fogerty with Foo Fighters // Wrote A Song For Everyone 05. -

Apple Label Discography

Apple Label Discography 100-800 series (Capitol numbering series) Apple Records was formed by John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr in 1968. The Apple label was intended as a vehicle for the Beatles, their individual recordings and the talent they discovered. A great deal of what appeared on Apple was pretty self indulgent and experimental but they did discover a few good singers and groups. James Taylor recorded his first album on the label. Doris Troy recorded a good soul album and there are 2 albums by John Lewis and the Modern Jazz Quartet. The Beatlesque group Badfinger also issued several albums on the label, the best of which was “Straight Up”. Apple Records fell apart in management chaos in 1974 and 1975 and a bitter split between the Beatles over the management of the company. Once the lawyers got involved everybody was suing everybody else over the collapse. The parody of the Beatles rise and the disintegration of Apple is captured hilariously in the satire “All You Need Is Cash: the story of the Rutles”. The Apple label on side 1 is black with a picture of a green apple on it, black printing. The label on side 2 is a picture of ½ an apple. From November 1968 until early 1970 at the bottom of the label was “MFD. BY CAPITOL RECORDS, INC. A SUBSIDIARY OF CAPITOL INDUSTRIES INC. USA”. From Early 1970 to late 1974, at the bottom of the label is “MFD. BY APPLE RECORDS” From late 1974 through 1975, there was a notation under the “MFD. -

March 2019 / Issue No

“I am hugely honoured “Guilty, I am - radicalised, “Being free doesn’t solve by the opportunity to I was. Yet I still find my your problems it just gives the National Newspaper for Prisoners & Detainees lead HMPPS at such an entire situation incredibly you the space to deal with important time.” Jo Farrar surreal.” Zakaria Amara them.” Melanie Myers a voice for prisoners since Newsround // page 10 Comment // page 31 Comment // page 27 March 2019 / Issue No. 237 / www.insidetime.org / A ‘not for profit’ publication/ ISSN 1743-7342 WORLD BOOK DAY 11 // MOTHER’S DAY 46 // INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY 54 An average of 60,000 copies distributed monthly Independently verified by the Audit Bureau of Circulations PAROLE REVOLUTION Justice Secretary David Gauke’s ‘landmark reform’ l Prisoners and victims l Process to be more l Victims still have no to have right of appeal transparent to counter veto on decisions to against decisions. ‘profound deficiencies’. release. Inside Time report whether there could have The judge would be able to been serious mistakes or legal either ask the original panel 14 flaws in the ruling. If the Jus- to review its decision or order Credit: HMP Hydebank Wood Under the new plans, victims tice Secretary decides that a fresh hearing by a new who want to challenge a deci- there is a case for the decision panel. The new system will sion to release a particular to be reviewed he will refer apply from this summer to New kids on the block! prisoner would be able to the appeal to a judge at the those with the most serious apply to the Justice Secretary, Parole Board. -

John Lennon, Yoko Ono E a Nova Esquerda 'We All Want to Change the World'

10.20396/ideias.v9i2.8655182 ‘We all want to change the world’: John Lennon, Yoko Ono e a Nova Esquerda Vanessa Pironato Milani1 Resumo: Este artigo tem por finalidade analisar, à luz do efervescente cenário dos anos 1960, o engajamento político de John Lennon e Yoko Ono, perceptível desde suas produções solo, e consolidado com o início de seu relacionamento, momento a partir do qual acabaram fortalecendo e ampliando seus atos artístico-políticos. Sendo assim, busca-se refletir sobre as produções musicais de tais artistas a partir da segunda metade da década 1960, demonstrando como também a música pode ser um ato revolucionário, para além dos protestos nas ruas, nos campi universitários e dos jornais e revistas undergrounds. Palavras-chave: Yoko Ono. John Lennon. Nova Esquerda. Engajamento. ‘We all want to change the world’: John Lennon, Yoko Ono and New Left Abstract: This paper aims to analyze, in the light of the effervescent scenario of the 1960s, the political engagement of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, perceptible from his solo productions, and consolidated with the beginning of their relationship, from which moment they strengthened and expanded their artistic-political acts. Thus, it is sought to reflect on the musical productions of such artists from the second half of the 1960s, demonstrating how music can also be a revolutionary act, in addition to street protests, university campuses and underground newspapers and magazines. Keywords: Yoko Ono. John Lennon. New Left. Engagement. 1 Doutoranda em História na Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, UNESP, Brasil, com financiamento Capes. E-mail: [email protected]. -

4Th & 5Th Grade

Saint Ann’s School Library, 2021 Suggested SUMMER READING for entering fifth & sixth graders Fiction ∞ Alkaf, Hanna. The Girl and the Ghost. If you like creepy stories, don’t miss this one, about a girl in Malaysia named Suraya, whose witch grandmother dies and leaves her a ghost. Suraya is thrilled, but is the ghost a gift or a curse? Or could it be both? ∞ Bradley, Kimberly Brubaker. The War that Saved My Life. Ada is 10 and has never been outside. She was born with a twisted foot that her mother considers an embarrassment, so she watches the world from her window in World War II-era London. One day, she gets a chance to leave the city with a group of kids who are being evacuated to safety from Nazi bombs. Is there finally hope for her? Sequel: The War I Finally Won. ∞ Broaddus, Maurice. The Usual Suspects. Thelonious is a prankster, and he’s always getting blamed for things, even if he’s innocent. When a gun is found near school and the principal rounds up “the usual suspects,” Thelonious and his best friend team up to figure out how it got there. ∞ Bruchac, Joseph. Rez Dogs. When COVID strikes, Mailan is at her grandparents’ home on the reservation and a mysterious dog shows up to protect them. This novel in verse chronicles their experience during lockdown, celebrates family stories, and addresses the terrible toll infectious diseases and government policies have taken on Native people in this country. ∞ Callender, Kacen. King and the Dragonflies. In his tight-knit Black community in a small Louisiana town, Saint Ann’s Digital Library King struggles with the sudden death of his brother, and misses his best friend, who has disappeared. -

Greatlakereviewspring'11.Pdf (1.402Mb)

The Great Lake Review is open to submissions throughout the year. Please send your fiction, creative nonfiction, dramatic writing, poetry and visual art as an attachment to: [email protected] The Great Lake Review Spring 2011 Editor-in-Chief Fiction Editors Amanda Nargi Marisa Dupras Megan Andersen Treasurer Non-Fiction Editor Marci Zebrowski Alex Carawan Managing Editors Poetry Editors Amber-Lee Jansen Fred Maxon Leigh Rusyn Charles Buckel Faculty Advisor Brad Korbesmeyer Special Thanks to: Creative Writing Faculty English Department Staff Art Department Staff Shannon Pritting-Penfield Library THE GREAT LAKE REVIEW IS NOW AVAILABLE ONLINE Thanks to the hard work of Shannon Pritting, the GLR has been made available in an online archive accessable through the Penfield Library website! Stop by and take the opportunity to read submissions from our first publication on at: http://www.oswego.edu/library/archives/Great_Lake_Review.html Table of Contents Poetry Raven by Kaline Mulvihill....................................................................................................9 1942 (Abridged Version) by Rebecca C. Wemesfelder ......................................................13 Scarless by Melanie Hoffman ............................................................................................19 Suddenly There was No Party at the Epicenter of a Beatles Tune by Melissa Bamerick ..21 A Forest of Faces by Rachel Walerstein ............................................................................27 Mermaid by Annie Hidley .................................................................................................29