Schofield Barracks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waipio Acres Kahaluu

Naval Cptr & Telecom Area Mstr Stn S tH Whitmore Village w y 04 8 S y 8 Molli Pond 0 tH Hw Ave) 3 w St re y mo 80 hit W StHwy 99 ( Wahiawa Wahiawa Reservoir Schofield Barracks Military Res Ku Tree Reservoir P Schofield Barracks Mil Res S t H w Schofield Barracks y 8 3 109th Congress of the United States ( Waikane K a m e h a m e h a r H St w a y u ) la a k Military Waik a Military Res Naval Fleet Operation Res Control Center Pacific Waikalani Dr Wheeler AFB Wikao St Wheeler Army Afld StHwy 99 Waipio Acres Kahaluu Kahaluu Pond Military Upper Kipapa Res Military Res Mililani DISTRICT Town Naval Computer and Kaneohe Station H2 Telecommunications Area Master Station Pacific 2 Kaneohe Marine Corps Air Sta Ahuimanu Halekou Pond Heeia Kaluapuhi S Pond t Pond H w y S Nuupia Pond 7 t H Nuupia 5 HONOLULU w 0 Pond ( y K 8 u 3 n 0 Kaneohe Bay ia R d Heeia ) Military Res Waipio S Waikele Br Naval t Magazine Lualualei H StHwy 99 w y ) 8 5 3 6 (K y a w h tH e S k ( i l 0 i 3 H 6 DISTRICT w wy Waikele Naval y StH Ammunition Dpo Naval ) aneohe Bay Dr) 0 (K Res 63 Pearl City wy 1 S tH Naval Res Waimalu Kaneohe d R H1 s Kailua s m e a c e c tr A S l H3 u Village a l v u a p N e Park l Naval S e t a Res H H1 w K y 8 StHwy 93 Camp H M 3 Waipahu Pearl City Naval Sta ) Aiea Smith d R a StHwy 99 H3 u il StHwya 61 (K Waipio Peninsula Naval Res Kaelepulu Pond Halawa Red Hill Naval Res Naval Res East Loch Pearl Harbor Ulumoku Fish Pond StHwy 72 StHwy 93 Middle Loch Maunawili Pearl Harbor StHwy 99 StHwy 63 Honolulu Cg Base Ford Island Naval Res Makalapa Tripler -

National Film Registry Titles Listed by Release Date

National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year Title Released Inducted Newark Athlete 1891 2010 Blacksmith Scene 1893 1995 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894-1895 2003 Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 2015 The Kiss 1896 1999 Rip Van Winkle 1896 1995 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 2012 Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 2002 President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 2000 The Great Train Robbery 1903 1990 Life of an American Fireman 1903 2016 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 1998 Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street 1905 2017 Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 2015 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 2005 A Trip Down Market Street 1906 2010 A Corner in Wheat 1909 1994 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 2004 Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 2003 Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 2005 White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 2008 Little Nemo 1911 2009 The Cry of the Children 1912 2011 A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 2011 From the Manger to the Cross 1912 1998 The Land Beyond the Sunset 1912 2000 Musketeers of Pig Alley 1912 2016 Bert Williams Lime Kiln Club Field Day 1913 2014 The Evidence of the Film 1913 2001 Matrimony’s Speed Limit 1913 2003 Preservation of the Sign Language 1913 2010 Traffic in Souls 1913 2006 The Bargain 1914 2010 The Exploits of Elaine 1914 1994 Gertie The Dinosaur 1914 1991 In the Land of the Head Hunters 1914 1999 Mabel’s Blunder 1914 2009 1 National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year -

2009 RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL MEDIA RELEASE for Details, Photographs Or Videos About RIIFF News Releases, Contact: Adam M.K

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 2009 RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL MEDIA RELEASE For Details, Photographs or Videos about RIIFF News Releases, Contact: Adam M.K. Short, Producing Director [email protected] • 401.861-4445 ERNEST BORGNINE TO RECEIVE 2009 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING ACTOR TO BE HONORED AT FESTIVAL’S 13TH YEAR CELEBRATION ON FRIDAY, AUGUST 7TH (PROVIDENCE, RI) Ernest Borgnine, who won the 1955 best actor Academy Award for his performance as a lovelorn butcher in the film “Marty” and is better known to a later generation of television viewers as the PT-boat skipper on “McHale’s Navy,” will receive a Lifetime Achievement award at this year’s Rhode Island International Film Festival (RIIFF) in early August. The award will be presented at the world premiere screening of his most recent film, director Greg Swartz's “Another Harvest Moon,” on Friday, August 7th at 7:00 p.m. The location for the screening will be the Columbus Theatre Arts Center at 270 Broadway. Tickets for this special event are $15.00 and can be purchased online at the Festival’s website: http://www.film-festival.org/Borgnine.php “Presenting Mr. Borgnine with the RIIFF Lifetime Achievement Award is deeply heartfelt for us at the Festival,” commented RIIFF’s Executive Director George T. Marshall. “He is such an amazingly accomplished actor; we are deeply honored to have him participate in this year’s event. His work has touched millions and set new standards; becoming a vibrant and critical part of the American experience.” Previous winners of the RIIFF Lifetime Achievement Award have been director Blake Edwards; actresses Cicely Tyson and Patricia Neal; and actors Seymour Cassel and Kim Chan. -

Schofield Barracks, 27Th Infantry Regiment

#191 ROBERT KINZLER: SCHOFIELD BARRACKS, 27TH INFANTRY REGIMENT John Martini (JM): It's December 3, 1991. My name is Ranger John Martini from the National Park Service. We're doing [an] oral history interview videotape with Mr. Robert Kinzler. Mr. Kinzler was a solider stationed at Schofield Barracks, 27th Infantry Regiment on December 7, 1941. At that time, he was a Private Third Class radio operator. He was then nineteen years of age. This oral history videotape is being produced in conjunction with the National Park Service, USS ARIZONA Memorial and KHET-TV. So, thanks for coming to speak with us. And the first question I always ask is when did you enlist and where did you enlist? Robert Kinzler (RK): I enlisted on the 24th of June, 1940 at Newark, New Jersey, and requested service in Hawaii. My purpose in doing that was to try to win an appointment to West Point by attending the West Point prep school which was being conducted here, or at the Schofield Barracks at the time. They had another one at Fort Dix, New Jersey, but that was only a few miles from my home, so I opted for Hawaii. And it took three months to get here. I didn't arrive here until early September, 1940 on the USAT REPUBLIC, a transport, which brought me from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Brooklyn Army base to Panama, to San Francisco, to Hawaii. I got here and they off loaded us from the ship, put us on trucks, drove us a few blocks to the Iwilei Railroad Station. -

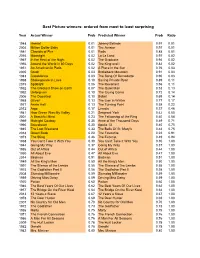

Best Picture Winners: Ordered from Most to Least Surprising

Best Picture winners: ordered from most to least surprising Year Actual Winner Prob Predicted Winner Prob Ratio 1948 Hamlet 0.01 Johnny Belinda 0.97 0.01 2004 Million Dollar Baby 0.01 The Aviator 0.97 0.01 1981 Chariots of Fire 0.01 Reds 0.88 0.01 2016 Moonlight 0.02 La La Land 0.97 0.02 1967 In the Heat of the Night 0.02 The Graduate 0.94 0.02 1956 Around the World in 80 Days 0.02 The King and I 0.82 0.02 1951 An American in Paris 0.02 A Place in the Sun 0.76 0.03 2005 Crash 0.03 Brokeback Mountain 0.91 0.03 1943 Casablanca 0.03 The Song Of Bernadette 0.90 0.03 1998 Shakespeare in Love 0.10 Saving Private Ryan 0.89 0.11 2015 Spotlight 0.06 The Revenant 0.56 0.11 1952 The Greatest Show on Earth 0.07 The Quiet Man 0.53 0.13 1992 Unforgiven 0.10 The Crying Game 0.72 0.14 2006 The Departed 0.10 Babel 0.69 0.14 1968 Oliver! 0.13 The Lion in Winter 0.77 0.17 1977 Annie Hall 0.13 The Turning Point 0.58 0.22 2012 Argo 0.17 Lincoln 0.37 0.46 1941 How Green Was My Valley 0.21 Sergeant York 0.42 0.50 2001 A Beautiful Mind 0.23 The Fellowship of the Ring 0.40 0.58 1969 Midnight Cowboy 0.35 Anne of the Thousand Days 0.49 0.71 1995 Braveheart 0.30 Apollo 13 0.40 0.75 1945 The Lost Weekend 0.33 The Bells Of St. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Transcending Masculinity (Re)Reading Rocky …Thirty Years Later

Transcending Masculinity (Re)READING ROCKY …THIRTY YEARS LATER by Heather Collette-VanDeraa NOTIONS OF MASCULINITY have been an epoch’s need to explore an experience that discussed in film scholarship for decades, with as yet has not been adequately formulated and the genre of action films, particularly that thematized” (131). The ‘experience’ that has of the boxing film, providing a most fertile yet to be adequately formulated in Rocky is a ground for discourse. While Rocky (1976) did construction of masculinity that must adapt not inaugurate the genre, it remains one of the to, and reflect, the changing cultural climate of seminal films of not only the boxing genre, but working- and middle-class values in light of civil of all American films, providing an archetype rights and gender equality. In his struggle to of masculinity that spawned a franchise. Many achieve champion status, Rocky Balboa navigates and emotional development, both of which are of these films repeat a theme of triumph a new cultural terrain marked by a disruption of achieved through his interpersonal relationships. against all odds that relies on a negotiation and traditional gender roles. While the hard-body/ Rocky Balboa’s masculinity is marked by a assertion of masculinity in its most physical action genre of films has presented an arguably personal catharsis of emotional self-actualization (and often violent) forms. Jurgen Reeder (1995) homogenous class of masculine iconography, that transcends his raw physicality and role asserts that “these films seem to be a kind of Rocky can be deconstructed today in light of an as an underdog boxer. -

Film Facts 5 Or More Competitive Awards

FILM FACTS 5 OR MORE COMPETITIVE AWARDS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 11 AWARDS Ben-Hur, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1959 (12 nominations) Titanic, 20th Century Fox and Paramount, 1997 (14 nominations) The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, New Line, 2003 (11 nominations) 10 AWARDS West Side Story, United Artists, 1961 (11 nominations) 9 AWARDS Gigi, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1958 (9 nominations) The Last Emperor, Columbia, 1987 (9 nominations) The English Patient, Miramax, 1996 (12 nominations) 8 AWARDS Gone with the Wind, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1939 (13 nominations) (plus 1 special Oscar and 1 Sci/Tech Award) From Here to Eternity, Columbia, 1953 (13 nominations) On the Waterfront, Columbia, 1954 (12 nominations) My Fair Lady, Warner Bros., 1964 (12 nominations) Cabaret, Allied Artists, 1972 (10 nominations) Gandhi, Columbia, 1982 (11 nominations) Amadeus, Orion, 1984 (11 nominations) Slumdog Millionaire, Fox Searchlight, 2008 (10 nominations) 7 AWARDS Going My Way, Paramount, 1944 (10 nominations) The Best Years of Our Lives, RKO Radio, 1946 (8 nominations) (plus 1 special Oscar to Harold Russell) The Bridge on the River Kwai, Columbia, 1957 (8 nominations) Lawrence of Arabia, Columbia, 1962 (10 nominations) Patton, 20th Century-Fox, 1970 (10 nominations) The Sting, Universal, 1973 (10 nominations) Out of Africa, Universal, 1985 (11 nominations) Dances With Wolves, Orion, 1990 (12 nominations) Schindler's List, Universal, 1993 (12 nominations) Shakespeare in Love, Miramax, 1998 (13 nominations) Gravity, Warner Bros., 2013 (10 nominations) -

Clinic/Hospital Location Address Phone Extra Info

Clinic/Hospital Location Address Phone Extra Info. Military Treatment Facilities Fort Shafter VTF Honolulu Bldg 435 Pierce Road 433-2271 Hickam VTF Honolulu Bldg 1864 Kuntz Avenue 449-6481 Schofield Barracks VTF Wahiawa 936 Duck Road 655-5889 655-5893 Kaneohe MCBH VTF Kaneohe Bldg 455 Pancoast Place 257-3643 24-Hour Emergency Hospitals Feather and Fur Kailua 25 Kaneohe Bay Dr., #132 254-1548 11 vets-Avians, Exotics VCA Family Animal Hospital Pearl City 98-1254 Kaahumanu St. 664-1753 12 vets-additional phone 484-9070 VET Emergency & Referral Center Honolulu 1347 Kapiolani Blvd, #103 735-7735 3 vets-Internist, Radiologist Waipahu-Waikele Pet Hospital Waipahu 94 Koaki Street 671-7387 11 vets- Avaian Honolulu Area Vet Clinics/Hospitals Aina Haina Pet Hospital Kaimuki 3405 Waialae Ave 732-9111 1 vet Aloha Animal Hospital Kahala 4224 Waialae Ave 734-2242 1-2 vets Animal Clinic of Honolulu Honolulu 1048 Koko Head Ave 734-0255 3 vets Animal Hospital of Hawaii Honolulu 3111 Castle Street 732-7387 1 vet Blue Cross Animal Hospital Honolulu 1318 Kapiolani Blvd 593-2532 2 vets Hawaii Veterinary Internal Med Pearl City 941 Kamehameha Hwy 455-3647 1 vet-Internal Medicine, Dental Extraction Hawaii Veterinary Vision Care Honolulu 1021 Akala Lane 593-7777 Board Cert Opthalmologist Honolulu Pet Clinic Honolulu 1115 Young Street 593-9336 1 vet Island Veterinary Care Molilii 830 Coolidge Street 944-0003 1 vet-House Calls, Bunnies, Exotics Kaka'ako Pet Hospital Honolulu 815 Queen St 592-9999 2 vets- Avians, Exotics, Rodents Kahala Pet Hospital Kahala 4819 Kilauea -

A Tribute to Ernest Borgnine by Jarrod Emerson

Rise Of The Everyman A Tribute to Ernest Borgnine by Jarrod Emerson SPECIAL FOR FILMS FOR TWO® Ernest Borgnine with the Oscar he won for Marty. Photo Credit: John McCoy/ZUMA Press/Newscom (1/21/11) In the 1995 comedy sequel Grumpier Old Men, “Jacob Goldman” (Kevin Pollack) mentions the name of an “available” woman to his lonely widower father “Max” (Walter Matthau). Upon hearing the woman’s name Max balks, replying, “She looks like Ernest Borgnine!” Having been born in the mid-1980’s I had no idea who Matthau’s character was referring to, but that would soon change. As my interest in cinema progressed, I began to notice the late actor popping up here and there. Eventually, two things occurred to me. Firstly, I am in complete agreement in that I wouldn’t be keen to date a woman who resembled Ernest Borgnine. Secondly, for anyone to remember Ernest Borgnine as “that homely actor” simply does not do him justice. He was one of Hollywood’s greatest – and long-lived – character actors, staying busy in film and television, right up to his death from heart failure last July at the age of 95. Perhaps best remembered as “McHale” from the beloved sitcom McHale’s Navy, that role was but the tip of the iceberg in terms of Borgnine’s capabilities. Over the course of six decades, Borgnine forged a richly diverse film career as he collaborated with multiple generations of talented filmmakers. His Academy Award for the heartwarming 1955 film Marty helped pave the way for future generations of immensely talented character actors. -

Guest: Gavan Daws Lss 125 (Length: 27:49) First Air Date: 6/10/08

GUEST: GAVAN DAWS LSS 125 (LENGTH: 27:49) FIRST AIR DATE: 6/10/08 Aloha no and welcome to Long Story Short. I’m Leslie Wilcox of PBS Hawaii. Today, on Long Story Short, we get to share stories with a professional storyteller – best known as an author, Gavan Daws. Australian transplant Gavan Daws was the first person to earn a PhD in Pacific history at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. The academic and teacher became the bestselling author of Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands, Land and Power in Hawaii, Holy Man: Father Damien of Molokai and many other books. Now he’s collaborated on an 1,100-page anthology, Honolulu Stories: Two Centuries of Writing – full of voices of Hawai‘i. You’re a storyteller in so many forms. Your latest form is this very hefty book with Bennett Hymer. What other ways have you told stories in your life? Well, if it comes down to twenty-four words or less, I suppose that all of my life has really been about words and audiences. Words is all I have; I have no other skills of any kind, either creative or financial. So it’s words; words are my currency. And I kinda grew up on the edge of the Outback in Australia, where when I was a kid, there was no radio, and where for a long time, there was no TV. And storytelling was what everybody did. And when you got old enough, which is around sixteen, you’d go into the pub two or three years below drinking age; and that was storytelling territory as well. -

Cinema-Booklet-Web.Pdf

1 AN ORIGINAL EXHIBITION BY THE MUSEO ITALO AMERICANO MADE POSSIBLE BY A GRANT FROM THE WRITTEN BY Joseph McBride CO-CURATED BY Joseph McBride & Mary Serventi Steiner ASSISTANT CURATORS Bianca Friundi & Mark Schiavenza GRAPHIC DESIGN Julie Giles SPECIAL THANKS TO American Zoetrope Courtney Garcia Anahid Nazarian Fox Carney Michael Gortz Guy Perego Anne Coco Matt Itelson San Francisco State University Katherine Colridge-Rodriguez Tamara Khalaf Faye Thompson Roy Conli The Margaret Herrick Library Silvia Turchin Roman Coppola of the Academy of Motion Walt Disney Animation Joe Dante Picture Arts and Sciences Research Library Lily Dierkes Irene Mecchi Mary Walsh Susan Filippo James Mockoski SEPTEMBER 18, 2015 MARCH 17, 2016 THROUGH THROUGH MARCH 6, 2016 SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 Fort Mason Center 442 Flint Street Rudolph Valentino and Hungarian 2 Marina Blvd., Bldg. C Reno, NV 89501 actress Vilma Banky in The Son San Francisco, CA 94123 775.333.0313 of the Sheik (1926). Courtesy of United Artists/Photofest. 415.673.2200 www.arteitaliausa.com OPPOSITE: Exhibit author and www.sfmuseo.org Thursdays through co-curator Joseph McBride (left) Tuesdays through Sundays 12 – 4 pm Sundays 12 – 5 pm with Frank Capra, 1985. Courtesy of Columbia Pictures. 2 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Italian American Cinema: From Capra to the Coppolas 6 FOUNDATIONS: THE PIONEERS The Long Early Journey 9 A Landmark Film: The Italian 10 “Capraesque” 11 The Latin Lover of the Roaring Twenties 12 Capra’s Contemporaries 13 Banking on the Movies 13 Little Rico & Big Tony 14 From Ellis Island to the Suburbs 15 FROM THE STUDIOS TO THE STREETS: 1940s–1960s Crooning, Acting, and Rat-Packing 17 The Musical Man 18 Funnymen 19 One of a Kind 20 Whaddya Wanna Do Tonight, Marty? 21 Imported from Italy 22 The Western All’italiana 23 A Woman of Many Parts 24 Into the Mainstream 25 ANIMATED PEOPLE The Golden Age – The Modern Era 26 THE MODERN ERA: 1970 TO TODAY Everybody Is Italian 29 Wiseguys, Palookas, & Buffoons 30 A Valentino for the Seventies 32 Director Frank Capra (seated), 1927.