Guest: Gavan Daws Lss 125 (Length: 27:49) First Air Date: 6/10/08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Film Registry Titles Listed by Release Date

National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year Title Released Inducted Newark Athlete 1891 2010 Blacksmith Scene 1893 1995 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894-1895 2003 Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 2015 The Kiss 1896 1999 Rip Van Winkle 1896 1995 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 2012 Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 2002 President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 2000 The Great Train Robbery 1903 1990 Life of an American Fireman 1903 2016 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 1998 Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street 1905 2017 Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 2015 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 2005 A Trip Down Market Street 1906 2010 A Corner in Wheat 1909 1994 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 2004 Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 2003 Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 2005 White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 2008 Little Nemo 1911 2009 The Cry of the Children 1912 2011 A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 2011 From the Manger to the Cross 1912 1998 The Land Beyond the Sunset 1912 2000 Musketeers of Pig Alley 1912 2016 Bert Williams Lime Kiln Club Field Day 1913 2014 The Evidence of the Film 1913 2001 Matrimony’s Speed Limit 1913 2003 Preservation of the Sign Language 1913 2010 Traffic in Souls 1913 2006 The Bargain 1914 2010 The Exploits of Elaine 1914 1994 Gertie The Dinosaur 1914 1991 In the Land of the Head Hunters 1914 1999 Mabel’s Blunder 1914 2009 1 National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year -

2009 RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL MEDIA RELEASE for Details, Photographs Or Videos About RIIFF News Releases, Contact: Adam M.K

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 2009 RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL MEDIA RELEASE For Details, Photographs or Videos about RIIFF News Releases, Contact: Adam M.K. Short, Producing Director [email protected] • 401.861-4445 ERNEST BORGNINE TO RECEIVE 2009 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING ACTOR TO BE HONORED AT FESTIVAL’S 13TH YEAR CELEBRATION ON FRIDAY, AUGUST 7TH (PROVIDENCE, RI) Ernest Borgnine, who won the 1955 best actor Academy Award for his performance as a lovelorn butcher in the film “Marty” and is better known to a later generation of television viewers as the PT-boat skipper on “McHale’s Navy,” will receive a Lifetime Achievement award at this year’s Rhode Island International Film Festival (RIIFF) in early August. The award will be presented at the world premiere screening of his most recent film, director Greg Swartz's “Another Harvest Moon,” on Friday, August 7th at 7:00 p.m. The location for the screening will be the Columbus Theatre Arts Center at 270 Broadway. Tickets for this special event are $15.00 and can be purchased online at the Festival’s website: http://www.film-festival.org/Borgnine.php “Presenting Mr. Borgnine with the RIIFF Lifetime Achievement Award is deeply heartfelt for us at the Festival,” commented RIIFF’s Executive Director George T. Marshall. “He is such an amazingly accomplished actor; we are deeply honored to have him participate in this year’s event. His work has touched millions and set new standards; becoming a vibrant and critical part of the American experience.” Previous winners of the RIIFF Lifetime Achievement Award have been director Blake Edwards; actresses Cicely Tyson and Patricia Neal; and actors Seymour Cassel and Kim Chan. -

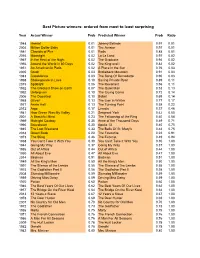

Best Picture Winners: Ordered from Most to Least Surprising

Best Picture winners: ordered from most to least surprising Year Actual Winner Prob Predicted Winner Prob Ratio 1948 Hamlet 0.01 Johnny Belinda 0.97 0.01 2004 Million Dollar Baby 0.01 The Aviator 0.97 0.01 1981 Chariots of Fire 0.01 Reds 0.88 0.01 2016 Moonlight 0.02 La La Land 0.97 0.02 1967 In the Heat of the Night 0.02 The Graduate 0.94 0.02 1956 Around the World in 80 Days 0.02 The King and I 0.82 0.02 1951 An American in Paris 0.02 A Place in the Sun 0.76 0.03 2005 Crash 0.03 Brokeback Mountain 0.91 0.03 1943 Casablanca 0.03 The Song Of Bernadette 0.90 0.03 1998 Shakespeare in Love 0.10 Saving Private Ryan 0.89 0.11 2015 Spotlight 0.06 The Revenant 0.56 0.11 1952 The Greatest Show on Earth 0.07 The Quiet Man 0.53 0.13 1992 Unforgiven 0.10 The Crying Game 0.72 0.14 2006 The Departed 0.10 Babel 0.69 0.14 1968 Oliver! 0.13 The Lion in Winter 0.77 0.17 1977 Annie Hall 0.13 The Turning Point 0.58 0.22 2012 Argo 0.17 Lincoln 0.37 0.46 1941 How Green Was My Valley 0.21 Sergeant York 0.42 0.50 2001 A Beautiful Mind 0.23 The Fellowship of the Ring 0.40 0.58 1969 Midnight Cowboy 0.35 Anne of the Thousand Days 0.49 0.71 1995 Braveheart 0.30 Apollo 13 0.40 0.75 1945 The Lost Weekend 0.33 The Bells Of St. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Transcending Masculinity (Re)Reading Rocky …Thirty Years Later

Transcending Masculinity (Re)READING ROCKY …THIRTY YEARS LATER by Heather Collette-VanDeraa NOTIONS OF MASCULINITY have been an epoch’s need to explore an experience that discussed in film scholarship for decades, with as yet has not been adequately formulated and the genre of action films, particularly that thematized” (131). The ‘experience’ that has of the boxing film, providing a most fertile yet to be adequately formulated in Rocky is a ground for discourse. While Rocky (1976) did construction of masculinity that must adapt not inaugurate the genre, it remains one of the to, and reflect, the changing cultural climate of seminal films of not only the boxing genre, but working- and middle-class values in light of civil of all American films, providing an archetype rights and gender equality. In his struggle to of masculinity that spawned a franchise. Many achieve champion status, Rocky Balboa navigates and emotional development, both of which are of these films repeat a theme of triumph a new cultural terrain marked by a disruption of achieved through his interpersonal relationships. against all odds that relies on a negotiation and traditional gender roles. While the hard-body/ Rocky Balboa’s masculinity is marked by a assertion of masculinity in its most physical action genre of films has presented an arguably personal catharsis of emotional self-actualization (and often violent) forms. Jurgen Reeder (1995) homogenous class of masculine iconography, that transcends his raw physicality and role asserts that “these films seem to be a kind of Rocky can be deconstructed today in light of an as an underdog boxer. -

Film Facts 5 Or More Competitive Awards

FILM FACTS 5 OR MORE COMPETITIVE AWARDS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 11 AWARDS Ben-Hur, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1959 (12 nominations) Titanic, 20th Century Fox and Paramount, 1997 (14 nominations) The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, New Line, 2003 (11 nominations) 10 AWARDS West Side Story, United Artists, 1961 (11 nominations) 9 AWARDS Gigi, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1958 (9 nominations) The Last Emperor, Columbia, 1987 (9 nominations) The English Patient, Miramax, 1996 (12 nominations) 8 AWARDS Gone with the Wind, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1939 (13 nominations) (plus 1 special Oscar and 1 Sci/Tech Award) From Here to Eternity, Columbia, 1953 (13 nominations) On the Waterfront, Columbia, 1954 (12 nominations) My Fair Lady, Warner Bros., 1964 (12 nominations) Cabaret, Allied Artists, 1972 (10 nominations) Gandhi, Columbia, 1982 (11 nominations) Amadeus, Orion, 1984 (11 nominations) Slumdog Millionaire, Fox Searchlight, 2008 (10 nominations) 7 AWARDS Going My Way, Paramount, 1944 (10 nominations) The Best Years of Our Lives, RKO Radio, 1946 (8 nominations) (plus 1 special Oscar to Harold Russell) The Bridge on the River Kwai, Columbia, 1957 (8 nominations) Lawrence of Arabia, Columbia, 1962 (10 nominations) Patton, 20th Century-Fox, 1970 (10 nominations) The Sting, Universal, 1973 (10 nominations) Out of Africa, Universal, 1985 (11 nominations) Dances With Wolves, Orion, 1990 (12 nominations) Schindler's List, Universal, 1993 (12 nominations) Shakespeare in Love, Miramax, 1998 (13 nominations) Gravity, Warner Bros., 2013 (10 nominations) -

A Tribute to Ernest Borgnine by Jarrod Emerson

Rise Of The Everyman A Tribute to Ernest Borgnine by Jarrod Emerson SPECIAL FOR FILMS FOR TWO® Ernest Borgnine with the Oscar he won for Marty. Photo Credit: John McCoy/ZUMA Press/Newscom (1/21/11) In the 1995 comedy sequel Grumpier Old Men, “Jacob Goldman” (Kevin Pollack) mentions the name of an “available” woman to his lonely widower father “Max” (Walter Matthau). Upon hearing the woman’s name Max balks, replying, “She looks like Ernest Borgnine!” Having been born in the mid-1980’s I had no idea who Matthau’s character was referring to, but that would soon change. As my interest in cinema progressed, I began to notice the late actor popping up here and there. Eventually, two things occurred to me. Firstly, I am in complete agreement in that I wouldn’t be keen to date a woman who resembled Ernest Borgnine. Secondly, for anyone to remember Ernest Borgnine as “that homely actor” simply does not do him justice. He was one of Hollywood’s greatest – and long-lived – character actors, staying busy in film and television, right up to his death from heart failure last July at the age of 95. Perhaps best remembered as “McHale” from the beloved sitcom McHale’s Navy, that role was but the tip of the iceberg in terms of Borgnine’s capabilities. Over the course of six decades, Borgnine forged a richly diverse film career as he collaborated with multiple generations of talented filmmakers. His Academy Award for the heartwarming 1955 film Marty helped pave the way for future generations of immensely talented character actors. -

Cinema-Booklet-Web.Pdf

1 AN ORIGINAL EXHIBITION BY THE MUSEO ITALO AMERICANO MADE POSSIBLE BY A GRANT FROM THE WRITTEN BY Joseph McBride CO-CURATED BY Joseph McBride & Mary Serventi Steiner ASSISTANT CURATORS Bianca Friundi & Mark Schiavenza GRAPHIC DESIGN Julie Giles SPECIAL THANKS TO American Zoetrope Courtney Garcia Anahid Nazarian Fox Carney Michael Gortz Guy Perego Anne Coco Matt Itelson San Francisco State University Katherine Colridge-Rodriguez Tamara Khalaf Faye Thompson Roy Conli The Margaret Herrick Library Silvia Turchin Roman Coppola of the Academy of Motion Walt Disney Animation Joe Dante Picture Arts and Sciences Research Library Lily Dierkes Irene Mecchi Mary Walsh Susan Filippo James Mockoski SEPTEMBER 18, 2015 MARCH 17, 2016 THROUGH THROUGH MARCH 6, 2016 SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 Fort Mason Center 442 Flint Street Rudolph Valentino and Hungarian 2 Marina Blvd., Bldg. C Reno, NV 89501 actress Vilma Banky in The Son San Francisco, CA 94123 775.333.0313 of the Sheik (1926). Courtesy of United Artists/Photofest. 415.673.2200 www.arteitaliausa.com OPPOSITE: Exhibit author and www.sfmuseo.org Thursdays through co-curator Joseph McBride (left) Tuesdays through Sundays 12 – 4 pm Sundays 12 – 5 pm with Frank Capra, 1985. Courtesy of Columbia Pictures. 2 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Italian American Cinema: From Capra to the Coppolas 6 FOUNDATIONS: THE PIONEERS The Long Early Journey 9 A Landmark Film: The Italian 10 “Capraesque” 11 The Latin Lover of the Roaring Twenties 12 Capra’s Contemporaries 13 Banking on the Movies 13 Little Rico & Big Tony 14 From Ellis Island to the Suburbs 15 FROM THE STUDIOS TO THE STREETS: 1940s–1960s Crooning, Acting, and Rat-Packing 17 The Musical Man 18 Funnymen 19 One of a Kind 20 Whaddya Wanna Do Tonight, Marty? 21 Imported from Italy 22 The Western All’italiana 23 A Woman of Many Parts 24 Into the Mainstream 25 ANIMATED PEOPLE The Golden Age – The Modern Era 26 THE MODERN ERA: 1970 TO TODAY Everybody Is Italian 29 Wiseguys, Palookas, & Buffoons 30 A Valentino for the Seventies 32 Director Frank Capra (seated), 1927. -

PROF. HELLERMAN's LIST of MUST-SEE OLD MOVIES * = Personal Favorite BOLD = Absolutely Essential

PROF. HELLERMAN'S LIST OF MUST-SEE OLD MOVIES * = Personal Favorite BOLD = Absolutely Essential 1930's Saboteur Modern Times *His Gal Friday *Petrified Forest *Lifeboat *I am a Prisoner of a Chain Gang *Key Largo *Gone With The Wind *The Treasure of Sierra Madre *The Wizard of Oz *To Have and Have Not It Happened One Night Dark Passage She Done Him Wrong Conflict *The Thin Man *Out of the Past *After The Thin Man *The Stranger The Great Ziegfield Laura My Man Godfried Murder, My Sweet Dinner at Eight The Killers Fantasia Nightmare Alley *March of the Wooden Soldiers The Lady From Shanghai *The Grapes of Wrath Gilda *You Can't Take it With You Criss Cross *Mr. Smith Goes to Washington The Postman Always Rings Twice *Mr. Deeds Goes to Town White Heat *Frankenstein Woman of the Year *Bride of Frankenstein *High Sierra Son of Frankenstein Fort Apache Dracula *The Ox Bow Incident Freaks All the King's Men Stagecoach *Double Indemnity San Francisco The Third Man *Destry Rides Again *It's a Wonderful Life The 39 Steps On the Town *The Lady Vanishes *All My Sons *Little Caesar *The Best Years of Our Lives Scarface The Roaring Twenties *Almost anything by The Marx Brothers: Ninotchka *Coconuts, *Room Service, *Night at the Opera, *Day at the Races, *Animal Crackers, *At the 1940's Circus, *Night in Casablanca, *Horse Feathers, *Citizen Kane *Duck Soup...... The Philadelphia Story Sullivan's Travels 1950's *Meet John Doe *The African Queen *The Maltese Falcon *The Caine Mutiny *Casablanca *The Harder They Fall *Sahara *In a Lonely Place Across the -

AFI Top 100 Films Rank Title Call Number(S) 1 Citizen Kane 33031 2

AFI Top 100 Films Rank Title Call number(s) 1 Citizen Kane 33031 2 Casablanca 29274, 36061 3 Godfather, The 33325 4 Gone with the wind 31403, 38925, 47377 5 Lawrence of Arabia 31374, 36801 6 Wizard of Oz, The 29675, 42265 7 Graduate, The 29652, 44876 8 On the waterfront 33643 9 Schindler's list 37021, 44983 10 Singin' in the rain 29097, 40658, 34674 11 It's a wonderful life 29658 12 Sunset Boulevard 38038 13 Bridge on the River Kwai, The 30207 14 Some like it hot 32549, 45612 15 Star Wars (1977) 38627, 43853 16 All about Eve 30386, 36046 17 African Queen 26383 (vhs only) 18 Psycho 31124 19 Chinatown 32085, 46209 20 One flew over the cuckoo's nest 31423, 34678, 42136 21 Grapes of wrath, The 42135, 37251, 46921 22 2001: a space odyssey 30302, 43455, 46520 23 Maltese falcon, The 32512, 44460, 46046 24 Raging bull 29667, 39125 25 E.T. The extra-terrestrial 34802 26 Dr. Strangelove 29648, 31316, 32945, 38786 27 Bonnie & Clyde 31594, 47655 28 Apocalypse now 30201, 33503, 45147 29 Mr. Smith goes to Washington 32109, 45302 30 Treasure of the Sierra Madre 36624 31 Annie Hall 29472 32 Godfather part II, The 33326 33 High noon 29655, 34805 34 To kill a mockingbird 30303, 40875 35 It happened one night 30674, 45302 36 Midnight cowboy 29663, 42256 37 Best years of our lives 32175 38 Double indemnity 31142, 43421 39 Doctor Zhivago 33547 40 North by Northwest 31332, 38381 41 West side story 29099, 35908 42 Rear window 31125 43 King Kong (1933) 41365 44 Birth of a nation, The 32177, 37457 45 Streetcar named Desire 31422, 43295, 43949 46 Clockwork orange, -

Films Receiving 10 Or More Nominations

FILM FACTS 10 OR MORE NOMINATIONS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 14 NOMINATIONS All about Eve, 20th Century-Fox, 1950 (6 awards) Titanic, 20th Century Fox and Paramount, 1997 (11 awards) 13 NOMINATIONS Gone with the Wind, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1939 (8 awards, plus one Special and one Sci/Tech awards) From Here to Eternity, Columbia, 1953 (8 awards) Mary Poppins, Buena Vista Distribution Company, 1964 (5 awards) Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Warner Bros., 1966 (5 awards) Forrest Gump, Paramount, 1994 (6 awards) Shakespeare in Love, Miramax, 1998 (7 awards) The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, New Line, 2001 (4 awards) Chicago, Miramax, 2002 (6 awards) The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Paramount and Warner Bros., 2008 (3 awards) 12 NOMINATIONS Mrs. Miniver, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1942 (6 awards) The Song of Bernadette, 20th Century-Fox, 1943 (4 awards) Johnny Belinda, Warner Bros., 1948 (1 award) A Streetcar Named Desire, Warner Bros., 1951 (4 awards) On the Waterfront, Columbia, 1954 (8 awards) Ben-Hur, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1959 (11 awards) Becket, Paramount, 1964 (1 award) My Fair Lady, Warner Bros., 1964 (8 awards) Reds, Paramount, 1981 (3 awards) Dances With Wolves, Orion, 1990 (7 awards) Schindler's List, Universal, 1993 (7 awards) The English Patient, Miramax, 1996 (9 awards) Gladiator, DreamWorks and Universal, 2000 (5 awards) The King's Speech, The Weinstein Company, 2010 (4 awards) Lincoln, Walt Disney/20th Century Fox, 2012 (2 awards) The Revenant, 20th Century Fox, 2015 (3 awards) 11 NOMINATIONS Mr. Smith -

Film Scr Ipts Online S Er

learn more at alexanderstreet.com S ONLINE FILM SCRIPTS ERIES From Here to Eternity Black Hawk Down The African Queen Fury Ben Hur Body Heat Mr. Deeds Goes to Town King Kong American Gigolo Double Indemnity Predator Suspicion Leaving Las Vegas His Girl Friday Trading Places Swing Time The Maltese Falcon Sunset Boulevard 2001: A Space Odyssey The Sting The Shining Urban Cowboy Platoon Billy Liar Unforgiven Broadcast News The Big Chill Comfort and Joy Blade Runner Pan’s Labyrinth Night of the Hunter The Jazz Singer State and Main Witness The Spanish Prisoner Tender Mercies Hotel Rwanda In the Line of Fire Rebel Without a Cause The Lavender Hill Mob Span’glish The Last Detail The Hustler Mr. Smith Goes to Washington Gods and Monsters Taxi Driver Mean Streets The Last Temptation of Christ Ararat Out of the Past Nashville The Magnificent Ambersons Film Scripts Online Series We watch, discuss, and analyze movies—but rarely do we read the scripts. While some well-known film scripts have appeared in print, most have never been published in any format. The scholar’s struggle to locate original scripts involves complicated permissions and negotiations, and holders of scripts are often reluctant to lend rare and unique documents. The Film Scripts Online Series makes Content available, for the first time, accurate and authorized versions of copyrighted The Film Scripts Online Series was recently screenplays. Now film scholars can expanded with Volume II to include 500 compare the writer’s vision with the new screenplays, along with monographs producer’s and director’s interpretations including the Film Classics series from from page to screen.