Get Prepared for What's Ahead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listing of Institutions and Majors That Bachelor Graduates Attend for Graduate and Professional Education

Listing of institutions and majors that bachelor graduates attend for graduate and professional education 2015-2016 Peirce College Bachelor Graduates College Name Enrollment Major COMMUNITY COLLEGE OF PHILADELPHIA SCIENCE COMMUNITY COLLEGE OF PHILADELPHIA CULTURE SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY DREXEL UNIVERSITY COMPUTER SCIENCE PBC DREXEL UNIVERSITY DATA SCIENCE DREXEL UNIVERSITY CYBERSECURITY DREXEL UNIVERSITY INFORMATION SYSTEMS EASTERN GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE TEACHER ED‐EC GWYNEDD MERCY UNIVERSITY NON MATRICULATED HOLY FAMILY UNIVERSITY ‐ GRADS ACCOUNTING LA SALLE UNIVERSITY ACCOUNTING MERCER COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE LIBERAL ARTS NORTHAMPTON COMMUNITY COLLEGE EARLY CHILD‐LEADERSHP SD MASTER OF SCIENCE IN INFORMATION SYSTEMS STRAYER UNIVERSITY‐WASHINGTON CONCENTRATION IN COMPUTER FORENSICS MAN JACK WELCH MASTER IN BUSINESS STRAYER UNIVERSITY‐WASHINGTON ADMINISTRATION PROGRAM MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION STRAYER UNIVERSITY‐WASHINGTON CONCENTRATION IN ACQUISITION MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION CONCENTRATION IN CLINICAL STRAYER UNIVERSITY‐WASHINGTON CA TEMPLE UNIVERSITY BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION THOMAS EDISON STATE UNIVERSITY COMPUTER SCIENCE THOMAS JEFFERSON UNIVERSITY‐ EAST FALLS CAMPUS INNOVATION MBA THOMAS JEFFERSON UNIVERSITY‐ POPULATION OF HEALTH GRADUATE POP HLTH NON DEGREE UNIVERSITY OF THE ROCKIES ONLINE HUMAN SERVICES MA PROGRAM UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LAW (JD) WALDEN UNIVERSITY INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY WALDEN UNIVERSITY HEALTH ADMINISTRATION WEST CHESTER UNIVERSITY WESTERN GOVERNORS UNIVERSITY BUSINESS WIDENER UNIVERSITY -

Guide, Edward J. Stemmler Papers (UPT 50 S825)

A Guide to the Edward J. Stemmler Papers 1942-1999 8.0 Cubic feet UPT 50 S825 Prepared by Kaiyi Chen October 2009 The University Archives and Records Center 3401 Market Street, Suite 210 Philadelphia, PA 19104-3358 215.898.7024 Fax: 215.573.2036 www.archives.upenn.edu Mark Frazier Lloyd, Director Edward J. Stemmler Papers UPT 50 S825 TABLE OF CONTENTS PROVENANCE...............................................................................................................................1 ARRANGEMENT...........................................................................................................................1 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE................................................................................................................1 SCOPE AND CONTENT...............................................................................................................2 CONTROLLED ACCESS HEADINGS.........................................................................................3 INVENTORY.................................................................................................................................. 5 APPOINTMENT BOOK...........................................................................................................5 CERTIFICATE, AWARDS, ETC............................................................................................ 6 CORRESPONDENCE...............................................................................................................8 GENERAL FILES...................................................................................................................12 -

Undergraduate Catalog 2016-2018

UNDERGRADUATE2016 – 2018 CATALOG caring • learning • integrity • faith • teamwork • service IMMACULATA UNIVERSITY ACCREDITATION Immaculata University is currently granted accreditation by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, 3624 Market Street, 2nd Floor West, Philadelphia, PA 19104; (267) 284–5000; website: www.msche.org. The Immaculata University associates and baccalaureate business programs are currently granted accreditation and the accounting programs are also granted separate specialized accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs, 11520 West 119th Street, Overland Park, Kansas 66213; (913) 339-9356. Immaculata University, offering the Bachelor of Arts in Music, Bachelor of Music in Music Education, Bachelor of Music in Music Therapy, and Master of Arts in Music Therapy, is accredited by the National Association of Schools of Music, 11250 Roger Bacon Drive, Suite 21, Reston, VA 20190-5248; (703) 437-0700. The Master of Science in Nursing and the Bachelor of Science in Nursing are accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, One Dupont Circle, NW, Suite 530, Washington, DC 20036; (202) 887-6791. The Bachelor of Science program in Athletic Training is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE), 6835 Austin Center Blvd, Suite 250, Austin, TX 78731-3101 The Dietetic Internship is currently granted accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120 South Riverside Plaza, Suite 2000, Chicago, IL, 60606-6995; 800-877-1600, ext. 5400. The Didactic Program in Dietetics is currently granted accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120 South Riverside Plaza, Suite 2000, Chicago, IL, 60606-6995; 800-877-1600, ext. -

Course Catalog 2019 - 2020

COURSE CATALOG 2019 - 2020 mc3.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS COLLEGE FACULTY AND STAFF.................................................................................................2 1 COLLEGE FACULTY AND STAFF Cheryl L. Dilanzo, R.T. (R), Director of Radiography B.S. Thomas Jefferson University M.S. University of Pennsylvania Therol Dix, Dean of Arts and Humanities COLLEGE FACULTY B.A. University of California, Los AngelesM.A. University of Pennsylvania J.D. Georgetown University AND STAFF Bethany Eisenhart, Part-Time Career Coach ADMINISTRATION B.S. DeSales University Kimberly Erdman, Director of Dental Hygiene A.A.S., B.S. Pennsylvania College of Technology Office of the President M.S. University of Bridgeport Victoria L. Bastecki-Perez, President Katina Faulk, Administrative Director for Academic Initiatives D.H. University of Pittsburgh A.S., B.S. Pennsylvania College of Technology B.S. Edinboro University of Pennsylvania M.B.A. Excelsior College M.Ed, Ed.D. University of Pittsburgh Gaetan Giannini, Dean of Business and Entrepreneurial Initiatives Candy K. Basile, Administrative Support Secretary B.S. Temple University A.A.S. Montgomery County Community College M.B.A. Seton Hall University Deborah Rogers, Executive Assistant to the College’s Board of Trustees Ed.D. Gwynedd Mercy University A.A.S. Montgomery County Community College Suzanne Vargus Holloman, WIF Grant Project Director B.S. Syracuse University Academic Affairs M.B.A. Drexel University Gloria Oikelome, Interim Vice President of Academic Affairs and Dean of Sean Hutchinson, Coordinator of Integrated Learning Health Sciences B.A., M.A. La Salle University B.S. Bethel University Alfonzo Jordan, Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Lab M.S. Long Island University Manager Ed.D. -

SARA SHAW 430 Leah Drive Fort Washington, PA 19034 (267)280-3221 [email protected] EDUCATION

SARA SHAW 430 Leah Drive Fort Washington, PA 19034 (267)280-3221 [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D. in Human Development and Family Studies (Anticipated 2017) University of Delaware (Newark, DE) Certificate in Statistics (Anticipated 2017) University of Delaware (Newark, DE) M.S. in Experimental Psychology (2013) Saint Joseph’s University (Philadelphia, PA) B.A. in Psychology (2011) Graduated Cum Laude La Salle University (Philadelphia, PA) HONORS/AWARDS People’s Emergency Center Visiting Scholar. (2016). Award given to a promising scholar practicing community research to better the lives of families experiencing homelessness in Philadelphia. Poster Winner, 2nd Place. (2015). Award given at the 37th Annual Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management Fall Conference, Miami, FL. Strattner-Gregory Child Advocacy Award, University of Delaware. (2015). Award for a graduate student who shows promise of becoming a strong advocate for children. RESEARCH FUNDING Sigma Xi Student Research Grant (January 2013). Grant awarded for funding of my project examining the ability of adolescents with autism to detect and identify disgusting odors. ($350) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCES: Academic Appointments: Lecturer University of Delaware, Human Development and Family Studies Department, (2016) Research: Co-Investigator Building Early Links for Learning, People’s Emergency Center, Villanova University, Villanova University, & University of Delaware. (2016-Present). Project funded by the William Penn Foundation. Responsibilities: Serve as the lead investigator for the evaluation of the self-assessment tool for use in shelters. Lead Research Assistant Parents and Children Together, University of Delaware, Rutgers University, & Villanova University (PACT). (2014-Present). Responsibilities: Serve as a lead graduate research assistant for the PACT project. -

NSSE 2019 Selected Comparison Groups Dominican University

NSSE 2019 Selected Comparison Groups Dominican University IPEDS: 148496 NSSE 2019 Selected Comparison Groups About This Report Comparison Groups The NSSE Institutional Report displays core survey results for your students alongside those of three comparison groups. In May, your institution was invited to customize these groups via a form on the Institution Interface. This report summarizes how your comparison groups were constructed and lists the institutions within them. NSSE comparison groups may be customized by (a) identifying specific institutions from the list of all 2018 and 2019 NSSE participants, (b) composing the group by selecting institutional characteristics, or (c) a combination of these. Institutions that chose not to customize received default groupsa that provide relevant comparisons for most institutions. Institutions that appended additional question sets in the form of Topical Modules or through consortium participation were also invited to customize comparison groups for those reports. The default for those groups was all other 2018 and 2019 institutions where the questions were administered. Please note: Comparison group details for Topical Module and consortium reports are documented separately in those reports. Your Students' Comparison Comparison Comparison Report Comparisons Responses Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Comparison groups are located in the institutional reports as illustrated in the mock report at right. In this example, the three groups are "Admissions Overlap," "Carnegie UG Program," and "NSSE Cohort." Reading This Report This report consists of Comparison Group Name three sections that The name assigned to the provide details for each comparison group is listed here. of your comparison groups, illustrated at How Group was Constructed right. -

Undergraduate Catalog 2014-2016

12 2014 Catalog UNDERGRADU ATE IMMACULATA UNIVERSITY 2014-16 Undergraduate Catalog caring learning integrity faith teamwork service Accreditation Immaculata University is currently granted accreditation by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, 3624 Market Street, 2nd Floor West, Philadelphia, PA 19104; (267) 284–5000; website: www.msche.org. The Immaculata University associates and baccalaureate business programs are currently granted accreditation and the accounting programs are also granted separate specialized accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs, 11520 West 119th Street, Overland Park, Kansas 66213; (913) 339-9356. Immaculata University, offering the Bachelor of Arts in Music, Bachelor of Music in Music Education, Bachelor of Music in Music Therapy, and Master of Arts in Music Therapy, is accredited by the National Association of Schools of Music, 11250 Roger Bacon Drive, Suite 21, Reston, VA 20190-5248; (703) 437-0700. The Master of Science in Nursing and the Bachelor of Science in Nursing are accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, One Dupont Circle, NW, Suite 530, Washington, DC 20036; (202) 887-6791. The Bachelor of Science program in Athletic Training is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE), 6835 Austin Center Blvd, Suite 250, Austin, TX 78731-3101. The Dietetic Internship is currently granted accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120 South Riverside Plaza, Suite 2000, Chicago, IL, 60606-6995; 800-877-1600, ext. 5400. The Didactic Program in Dietetics is currently granted accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120 South Riverside Plaza, Suite 2000, Chicago, IL, 60606-6995; 800-877-1600, ext. -

Mbb Media Guide 11-12 Layout 1

QUICK FACTS School: La Salle University Location: Philadelphia, PA Earl Total Enrollment: 7,331 (4,673 undergraduates) Pettis Founded: 1863 President: Brother Michael J. McGinniss, F.S.C., Ph.D. Web Site: www.lasalle.edu Athletic Web Site: www.goexplorers.com Athletic Phone: 215-951-1425 Nickname: Explorers Colors: Blue (540) and Gold (7406) Home Court/Capacity: Tom Gola Arena (3,400) Athletic Director: Dr. Thomas Brennan Senior Associate Athletic Director: John Lyons Associate Athletic Director: Kale Beers Assistant Athletic Director: Mary Ellen Wydan Assistant Athletic Director: Chris Kane Basketball Information Head Coach (alma mater/year): Dr. John Giannini (North Central College ’84) Record at School (years): 98-115/8th Overall Record (years): 395-264/22nd Assistants (alma mater/years at La Salle): Horace Owens (Rhode Island ’83/8th) Harris Adler (Univ. of the Sciences ’98/8th) Will Bailey (UAB ‘98/2nd) Director of Operations: Sean Neal (La Salle ’07/4th) Video Coordinator: Terrence Stewart (Rowan ’96/3rd) Basketball Office Phone: 215-951-1518 Best Time to Reach Coach: Contact SID 2010-11 Record (Conference Record/Finish): 15-18 (6-10/T-10th) All-Time NCAA Tournament Record: 11-10 (11 appearances) All-Time NIT Record: 9-10 (11 appearances) Letterwinners Returning/Lost: 6/5 Starters Returning/Lost: 2/3 Media Information WHY WE ARE THE EXPLORERS La Salle University’s nickname – the Explorers – Assistant AD/Communications: Kevin Bonner was announced by the Collegian in March 1932 as Office Phone: 215-951-1513 the winning entry to a student contest. However, in the fall of 1931, a Baltimore sportswriter cover- Cell Phone: 484-880-3382 ing the La Salle/St. -

Procurement Transformation Powered by People Supply Chain

PROCUREMENT TRANSFORMATION POWERED BY PEOPLE SUPPLY CHAIN 173 174 PROCUREMENT TRANSFORMATION IN THE HEART OF PHILADELPHIA WRITTEN BY ANDREW WOODS PRODUCED BY DENITRA PRICE DREXEL UNIVERSITY SUPPLY CHAIN WE SPEAK TO ASSISTANT VICE PRESIDENT OF PROCUREMENT SERVICES JULIE ANN JONES REGARDING DREXEL UNIVERSITY’S PROCUREMENT TRANSFORMATION rocurement is undergoing nothing short of a revolution right now, P with technology transforming both operations and capabilities far beyond merely 175 a back-office function. Purchasing goods 176 and services strategically with an emphasis on value and cost savings has become a staple of modern business practice, and higher education is not exempt from this trend. Rising tuition costs and changes in enrollment patterns to more affordable options have caused budgets to tighten, leading to mergers and even closures among some smaller, private educational institutions. In this environ- ment, colleges and universities are re-evalu- ating their purchasing policies and procedures in order to maximize the student tuition dollar, reduce expenses, and remain competitive. Drexel University, located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is one such institution, having FEBRUARY 2019 www.businesschief.com DREXEL UNIVERSITY SUPPLY CHAIN “ WE TRY OUR BEST TO PARTNER WITH DEPARTMENTS TO MAKE SURE THEY’RE GETTING THE BEST VALUE” — Julie Ann Jones, Assistant Vice President Procurement Services 178 recently expanded its Procurement involves an annual spend of approxi- Services department under new mately $350mn across a diverse range leadership. Julie Ann Jones joined of departments, and transitioning this Drexel, the 15th largest private university function through the prism of social in the US, last January as Assistant responsibility and economic inclusion Vice President of Procurement Services. -

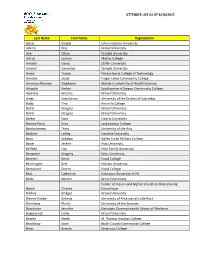

ATTENDEE LIST AS of 8/30/2017 Last Name First

ATTENDEE LIST AS OF 8/30/2017 Last Name First Name Organization Abras Chadia Johns Hopkins University Adkins Krys Drexel University Ake Ethan Temple University Alcruz Joanna Molloy College Amaker Corey Claflin University Amaral Genevive Temple University Amey Tracey Pennsylvania College of Technology Amidon Jacob Finger Lakes Community College Amonoo-Monney Stephanie Western University of Health Sciences Ashpole Amber Southwestern Oregon Community College Asprakis Antonis Drexel University Awgu Ezechukwu University of the District of Columbia Babb Tina Amarillo College Baird Douglas Drexel University Baird Douglas Drexel University Barker Gina Liberty University Barone Pricci Erica Lackawanna College Bartholomew Tracy University of the Arts Basford Letitia Hamline University Basu Sukalpa Valley Forge Military College Bauer Jeremi Post University Belfield Lisa Holy Family University Benjamin Gregory Salus University Bennett Kevin Hood College Bennington Bret Hofstra University Bertazzoni Donna Hood College Best Catherine Kutztown University of PA Betts Kristen Drexel University Center of Inquiry and Higher Education Data Sharing Blaich Charles Consortium Blakely Bridget Drexel University Blevins-Knabe Belinda University of Arkansas at Little Rock Blumberg Phyllis University of the Sciences Boardman Jennifer Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine Bogunovich Emily Drexel University Bowen Heath St. Thomas Aquinas College Bradshaw Scott Bucks County Community College Bretz Brenda Dickinson College ATTENDEE LIST AS OF 8/30/2017 Bryant Sharman Kutztown University of PA Buiting Lotte Drexel University Bullock Angela University of the District of Columbia Burns Alicia Lackawanna College Burrack Frederick Kansas State University Burrows Timothy Virginia Military Institute Callahan Rachel Drexel University Calzaferri Gina Temple University Campbell Joanna Bergen Community College Capps Shannon Drexel University Carbonaro Suzanne University of the Sciences Carcillo Anthony Wilmington University Cardozo Mario Kutztown University of PA Carelli, Jr. -

Graduate and Professional Education Statistics

Listing of institutions and majors that bachelor graduates attend for graduate and professional education 2016-2017 Peirce College Bachelor Graduates College Name Enrollment Major ALVERNIA UNIVERSITY CMTY SRVC ECON LDR AMERICAN INTERCONTINENTAL UNIVERSITY AMERICAN PUBLIC UNIVERSITY SYSTEM CYBERSECURITY STUDIES BOSTON COLLEGE HEALTHCARE ADMIN CABRINI UNIVERSITY SPECIAL ED PREK 8 CAIRN UNIVERSITY RELIGION CAPELLA UNIVERSITY GLOBAL OPS SUPPLY CHN MGMT COMMUNITY COLLEGE OF PHILADELPHIA CULTURE SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY DEVRY UNIVERSITY INFORMATION SYSTEMS MGMT DREXEL UNIVERSITY ‐ HEALTH SCIENCES LEGAL STUDIES EXCELSIOR COLLEGE MASTER OF EDUCATION IN EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION AND EARLY CHILDHOOD SPECIAL GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY EDU GWYNEDD MERCY UNIVERSITY BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY CAREY BUSINESS SCHOOL LA SALLE UNIVERSITY FINANCE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY MBA ORLEANS TECHNICAL COLLEGE BUILDING MAINTENANCE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY ROBERT MORRIS UNIVERSITY CYBER SECURITY AND INFO ASSURANCE(FOP) ROXBOROUGH MEMORIAL HOSPITAL SOUTHERN NEW HAMPSHIRE‐ 10WEEK ACCOUNTING ST JOSEPH'S UNIVERSITY GENERAL ST JOSEPH'S UNIVERSITY HEALTH ADMINISTRATION ST JOSEPH'S UNIVERSITY COMPUTER SCIENCE ST JOSEPH'S UNIVERSITY CRIMINAL JUSTICE TEMPLE UNIVERSITY INFORMATION SCIENCE TECHNOLO TEMPLE UNIVERSITY IT AUDITING CYBER SECURITY THOMAS JEFFERSON UNIVERSITY THOMAS JEFFERSON UNIVERSITY‐ EAST FALLS CAMPUS TAXATION THOMAS JEFFERSON UNIVERSITY‐ EAST FALLS CAMPUS INNOVATION MBA UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND GLOBAL CAMPUS‐ GRADS MS CYBERSECURITY TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY -

Valedictorian Salutatorian James Glazar Ashley Myers

SENIOR ACCEPTANCES AND PLANS Valedictorian Salutatorian James Glazar Ashley Myers Dominic Adelizzi Joseph Berardi Jade Broussard *Kean University *Cabrini College *Saint Joseph’s University Alvernia University Kutztown University Alvernia University Immaculata University Cabrini College +Tyler Berglund Immaculata University Robert M. Allegra III *Saint Joseph’s University La Salle University *Rowan University University of Delaware Rowan College at Gloucester County Angela Antonini Joseph K. Bobiak Jr. Widener University *Rowan University *Virginia Wesleyan College Clare Brown Brooke-Linh Aquilino Maura Bobrek *Montclair State University *Saint Joseph’s University *Rowan College at Gloucester Immaculata University Monmouth University County Monmouth University Mount St. Mary’s University Rutgers, The State University of Mount St. Mary’s University New Jersey St. Francis College Robert Aquilino Widener University *Rowan College at Gloucester +Katherine Bogan County *Villanova University Joseph Robert Brown Liberty University Loyola University Maryland *Prince George’s County Robert Morris University Quinnipiac University Community College University of Maryland University of Connecticut University of North Carolina Michael Buonanno Brian Earl Raymond Bohrer *Rutgers, The State University of +William Asterino III *Rowan College at Gloucester New Jersey *Saint Joseph’s University County Chestnut Hill College University of Delaware Rider University Alexa Bonomo Danielle N. Baxter *Rowan University Isabella Carmela Cammarata *Gwynedd-Mercy