The Nature and Origin of the Luminescence of Diamond by Sir C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microstructural, Mechanical, Corrosion and Cytotoxicity Characterization of Porous Ti-Si Alloys with Pore-Forming Agent

materials Article Microstructural, Mechanical, Corrosion and Cytotoxicity Characterization of Porous Ti-Si Alloys with Pore-Forming Agent Andrea Školáková 1,*, Jana Körberová 1 , Jaroslav Málek 2 , Dana Rohanová 3, Eva Jablonská 4, Jan Pinc 1, Pavel Salvetr 1 , Eva Gregorová 3 and Pavel Novák 1 1 Department of Metals and Corrosion Engineering, University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, Technická 5, 166 28 Prague 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (J.P.); [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (P.N.) 2 UJP Praha a.s., Nad Kamínkou 1345, 156 10 Prague 16, Czech Republic; [email protected] 3 Department of Glass and Ceramics, University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, Technická 5, 166 28 Prague 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] (D.R.); [email protected] (E.G.) 4 Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, Technická 5, 166 28 Prague 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-220-444-055 Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 7 December 2020; Published: 9 December 2020 Abstract: Titanium and its alloys belong to the group of materials used in implantology due to their biocompatibility, outstanding corrosion resistance and good mechanical properties. However, the value of Young’s modulus is too high in comparison with the human bone, which could result in the failure of implants. This problem can be overcome by creating pores in the materials, which, moreover, improves the osseointegration. Therefore, TiSi2 and TiSi2 with 20 wt.% of the pore-forming agent (PA) were prepared by reactive sintering and compared with pure titanium and titanium with the addition of various PA content in this study. -

Experimental and Computational Study of Fracturing in an Anisotropic Brittle Solid

Mechanics of Materials 28Ž. 1998 247±262 Experimental and computational study of fracturing in an anisotropic brittle solid Abbas Azhdari 1, Sia Nemat-Nasser ) Center of Excellence for AdÕanced Materials, Department of Applied Mechanics and Engineering Sciences, UniÕersity of California-San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0416, USA Received 21 November 1996; revised 26 August 1997 Abstract For isotropic materials, stress- and energy-based fracture criteria lead to fairly similar results. Theoretical studies show that the crack-path predictions made by these criteria are not identical in the presence of strong material anisotropy. Therefore, experiments are performed to ascertain which criterion may apply to anisotropic materials. Notched specimens made from sapphire, a microscopically homogeneous and brittle solid, are used for the experiments. An attempt is made to locate the notch on different crystallographic planes and thus to examine the fracture path along different cleavage planes. The experimental observations are compared with the numerical results of the maximum tensile stress and the maximum energy-release rate criteria. It is observed that most of the notched specimens are fractured where the tensile stress is maximum, whereas the energy criterion fails to predict the fracture path of most of the specimens. For the tensile-stress Žn. s p s r g s fracture criterion, a dimensionless parameter, A ''2 R0 nn a Enn, is introduced, where nnand E nn, respectively, are the tensile stress and Young's modulus in the direction normal to the cleavage plane specified by the angle a Žthe fracture surface energy of this plane is ga . and R0 is a characteristic length, e.g. -

Activity 21: Cleavage and Fracture Maine Geological Survey

Activity 21: Cleavage and Fracture Maine Geological Survey Objectives: Students will recognize the difference between cleavage and fracture; they will become familiar with planes of cleavage, and will use a mineral's "habit of breaking" as an aid to identifying common minerals. Time: This activity is intended to take one-half (1/2) period to discuss cleavage planes and types and one (1) class period to do the activity. Background: Cleavage is the property of a mineral that allows it to break smoothly along specific internal planes (called cleavage planes) when the mineral is struck sharply with a hammer. Fracture is the property of a mineral breaking in a more or less random pattern with no smooth planar surfaces. Since nearly all minerals have an orderly atomic structure, individual mineral grains have internal axes of length, width, and depth, related to the consistent arrangement of the atoms. These axes are reflected in the crystalline pattern in which the mineral grows and are present in the mineral regardless of whether or not the sample shows external crystal faces. The axes' arrangement, size, and the angles at which these axes intersect, all help determine, along with the strength of the molecular bonding in the given mineral, the degree of cleavage the mineral will exhibit. Many minerals, when struck sharply with a hammer, will break smoothly along one or more of these planes. The degree of smoothness of the broken surface and the number of planes along which the mineral breaks are used to describe the cleavage. The possibilities include the following. Number of Planes Degree of Smoothness One Two Three Perfect Good Poor Thus a mineral's cleavage may be described as perfect three plane cleavage, in which case the mineral breaks with almost mirror-like surfaces along the three dimensional axes; the mineral calcite exhibits such cleavage. -

Correlation of the Mohs's Scale of Hardness with the Vickers' S Hardness Numbers

718 Correlation of the Mohs's scale of hardness with the Vickers' s hardness numbers. By E. WILFRED TAYLOR, C.B.E., F.R.M.S., F. Inst. P. Messrs. Cooke, Troughton & Simms, Ltd., York. [Read June 23, 1949.] INERALOGISTS have long been accustomed to describe hard- M ness with the aid of a scale devised by Friedrich Mohs, who lived from 1773 to 1839. The test is qualitative, each mineral in the scale being capable of scratching those that precede it, but the ten minerals have held their ground as a useful representative series with which it is now interesting to compare another method of estimating hard- ness. In the metallurgical world hardness is now usually expressed by means of the Vickers's hardness numbers or their equivalent, and the figures are derived from the size of the impression made by a diamond indenter in the form of a four-sided pyramid with the opposite faces worked to an included angle of 136 ~ More recently micro-hardness testers have been devised to enable minute impressions to be formed under light loads on small individual crystals of a metallic alloy, 1 and it occurred to the author to obtain hardness figures for the various types of optical glass by means of a scratch test with such an instrument. The intention was to draw a lightly loaded diamond across a polished glass surface and to measure the width of the resulting furrow. This method proved to be promising, but as an experiment a static indenter was also used, and it was dis- covered that glass was sufficiently plastic to take good impressions, so long as the load did not exceed 50 grams or thereabouts. -

Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota

Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-A This report concerns work done partly on behalj of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the , » Commission Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota By DOUGLAS M. SHERllDAN, HAL G. STEPHENS, MORTIMER H. STAATZ and JAMES J. NORTON PEGMATITES AND OTHER PRECAMBRIAN ROCKS IN THE SOUTHERN BLACK HILLS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-A This report concerns work done partly on behalf of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1957 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1.50 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.__________________________________________ 1 Geology Continued Introduction _______________________________________ 1 Peerless pegmatite Continued Location_____________________________________ 1 Chemical composition......____________ 17 History and production________________________ 2 Origin________ ____________________ _. 18 Past and present investigations.__________________ 3 Mineral deposits_____________________________ 21 Acknowledgments__________________________ 4 Mica__ _________ _________________________ 21 Mine workings _____________________________________ -

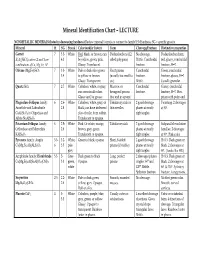

Mineral Identification Chart – LECTURE

Mineral Identification Chart – LECTURE NONMETALLIC MINERALS (listed in decreasing hardness) Review mineral formula to connect to family! H=Hardness; SG = specific gravity Mineral H SG Streak Color (and/or luster) Form Cleavage/Fracture Distinctive properties Garnet 7 3.5- White Red, black, or brown; can Dodecahedrons (12- No cleavage. Dodecahedron form, X3Y2(SiO4)3 where X and Y are 4.3 be yellow, green, pink. sided polygons) Brittle. Conchoidal red, glassy, conchoidal combinations of Ca, Mg, Fe, Al Glassy. Translucent. fracture. fracture, H=7. Olivine (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 7 3.3- White Pale or dark olive green Short prisms Conchoidal Green, conchoidal 3.4 to yellow or brown. (usually too small to fracture. fracture, glassy, H=7. Glassy. Transparent. see). Brittle. Usually granular. Quartz SiO2 7 2.7 White Colorless, white, or gray; Massive; or Conchoidal Glassy, conchoidal can occur in all colors. hexagonal prisms fracture. fracture, H=7. Hex. Glassy and/or greasy. that end in a point. prism with point end. Plagioclase Feldspar family: 6 2.6- White Colorless, white, gray, or Tabular crystals or 2 good cleavage Twinning. 2 cleavages Anorthite and Labradorite 2.8 black; can have iridescent thin needles planes at nearly at 90°. CaAl2Si2O8 to Oligoclase and play of color from within. right angles. Albite NaAlSi3O8 Translucent to opaque. Potassium Feldspar family: 6 2.5- White Pink. Or white, orange, Tabular crystals 2 good cleavage Subparallel exsolution Orthoclase and Microcline 2.6 brown, gray, green. planes at nearly lamellae. 2 cleavages KAlSi3O8 Translucent to opaque. right angles. at 90°. Pink color. Pyroxene family: Augite 5.5- 3.2- White, Green to black; opaque. -

Methods Used to Identifying Minerals

METHODS USED TO IDENTIFYING MINERALS More than 4,000 minerals are known to man, and they are identified by their physical and chemical properties. The physical properties of minerals are determined by the atomic structure and crystal chemistry of the minerals. The most common physical properties are crystal form, color, hardness, cleavage, and specific gravity. CRYSTALS One of the best ways to identify a mineral is by examining its crystal form (external shape). A crystal is defined as a homogenous solid possessing a three-dimensional internal order defined by the lattice structure. Crystals developed under favorable conditions often exhibit characteristic geometric forms (which are outward expressions of the internal arrangements of atoms), crystal class, and cleavage. Large, well- developed crystals are not common because of unfavorable growth conditions, but small crystals recognizable with a hand lens or microscope are common. Minerals that show no external crystal form but possess an internal crystalline structure are said to be massive. A few minerals, such as limonite and opal, have no orderly arrangement of atoms and are said to be amorphous. Crystals are divided into six major classes based on their geometric form: isometric, tetragonal, hexagonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, and triclinic. The hexagonal system also has a rhombohedral subdivision, which applies mainly to carbonates. CLEAVAGE AND FRACTURE After minerals are formed, they have a tendency to split or break along definite planes of weakness. This property is called cleavage. These planes of weakness are closely related to the internal structure of the mineral, and are usually, but not always, parallel to crystal faces or possible crystal faces. -

Characters Depending Upon Cohesion and Elasticity of Minerals

186 PHYSICAL MINERALOGY Thus, although it will be shown that the optical characters of crystals are in agreement in general with the symmetry of their form, they do not show all the variations in this symmetry. It is true, for example, that all directions are optically similar in a crystal belonging to any class under the isometric system; but this is obviously not true of its molecular cohesion, as may be shown by the cleavage. Again, all directions in a tetragonal crystal at right angles to the vertical axis are optically similar; but this again is not true of the cohesion. These points are further elucidated under the description of the special characters of each group. I. CHARACTERS DEPENDING UPON COHESION AND ELASTICITY 276. Cohesion, Elasticity. - The name cohesion is given to the force of attraction existing between the molecules of one and the.same body, in con- sequence of which they offer resistance to any influence tending to separate them, as in the breaking of a solid body or the scratching of its surface. Elasticity is the force which tends to restore the molecules of a body back into their original position, from which they have been disturbed, as when a body has suffered change of shape or of volume under pressure. The varying degrees of cohesion and elasticity for crystals of different minerals, or for different directions in the same crystal, are shown in the prominent characters: cleavage, fracture, tenacity, hardness; also in the gliding-planes, percussion-figures or pressure-figures, and the etching-figures. 277. Cleavage. - Cleavage is the tendency of a crystallized mineral to break in certain definite directions, yielding more or less smooth surfaces. -

Beryl Be3al2si6o18 C 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: Hexagonal

Beryl Be3Al2Si6O18 c 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: Hexagonal. Point Group: 6=m 2=m 2=m: Crystals prismatic to tabular, with 1010 , 0001 , and 1120 ; may be complexly terminated by pyramids, to 18 m and 180 t. Also rfadial,gtrfapichge, columf nar;ggranular to compact. Twinning: On hkil forms, rarely. f g Physical Properties: Cleavage: Imperfect on 0001 . Fracture: Conchoidal to uneven. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 7.5{8 VHN = 119f0{145g0, 1300 average. D(meas.) = 2.63{2.97 increasing with alkali content; 2.7 average. D(calc.) = 2.640 Optical Properties: Transparent to translucent. Color: Colorless, white, pale blue to sky-blue, bluish green through green to greenish yellow or yellow, rose to peach, deep pink to raspberry-red; may be zoned; commonly colorless in thin section. Streak: White. Luster: Vitreous, resinous. Optical Class: Uniaxial ({). Pleochroism: Weak to distinct; O = colorless, yellowish green, light blue, yellowish red; E = sea-green, blue, purplish red. ! = 1.567{1.610 ² = 1.565{1.599; increasing with alkali content. Cell Data: Space Group: P 6=mcc: a = 9.205{9.274 c = 9.187{9.249 Z = 2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Royalston, Massachusetts, USA. 2.867 (100), 3.254 (95), 7.98 (90), 4.60 (50), 3.99 (45), 3.015 (35), 2.523 (30) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) (1) (2) (3) SiO2 65.59 63.29 67.07 Na2O 0.26 1.23 Al2O3 18.25 17.76 18.97 Cs2O 3.79 FeO 1.16 Rb2O 0.05 BeO 13.46 10.79 13.96 LOI 0.70 1.10 Li2O 1.30 Total 99.42 99.31 100.00 (1) Mursinka, Russia; by electron microprobe. -

Germanium Concentration Associated to Sphalerite

Germanium concentration associated to sphalerite recrystallization: an example from the Pyrenean Axial Zone Alexandre Cugerone, Bénédicte Cenki-Tok, Emilien Oliot, Manuel Munoz, Alain Chauvet, Fabrice Barou, Kalin Kouzmanov, Stefano Salvi, Vincent Motto-Ros, Elisabeth Le Goff To cite this version: Alexandre Cugerone, Bénédicte Cenki-Tok, Emilien Oliot, Manuel Munoz, Alain Chauvet, et al.. Germanium concentration associated to sphalerite recrystallization: an example from the Pyrenean Axial Zone. 15th SGA Biennial Meeting on Life with Ore Deposits on Earth, Aug 2019, Glasgow, United Kingdom. hal-02915316 HAL Id: hal-02915316 https://hal-brgm.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02915316 Submitted on 2 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Germanium concentration associated to sphalerite recrystallization: an example from the Pyrenean Axial Zone Alexandre Cugerone, Bénédicte Cenki-Tok, Emilien Oliot, Manuel Munoz, Alain Chauvet, Fabrice Barou Géosciences Montpellier Kalin Kouzmanov University of Geneva Stefano Salvi Géosciences Environnement Toulouse Vincent Motto-Ros Institut Lumière et Matière Elisabeth Le Goff Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières (BRGM) Abstract. Germanium (Ge) is often found as trace 2013), but the presence of critical metals in these deposit- element in undeformed sphalerite (ZnS). -

A Crystallographic Analysis of the Tavernier Blue Diamond

ACRYSTALLOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE TAVERNIER BLUE DIAMOND Scott D. Sucher While the Tavernier Blue has been established as the “grandparent” of the Hope diamond, the only firsthand historical documentation for it is a 17th century line drawing of questionable accu- racy. It has been suggested that the diamond was crudely cut, conforming to the shape of the original crystal. If this is correct, then it should be possible to correlate the facets on the Tavernier Blue to the faces of a diamond crystal, and thus gain information on the crystallography of the original rough. This study used this information, the original drawings, and a computer model of the French Blue diamond generated from the laser scan of a recently discovered lead cast, to gen- erate a computer model of the Tavernier Blue. This new model completely encloses the comput- er model of the French Blue, conforms to Tavernier’s physical description, and establishes the ori- entation of the finished diamond within the original diamond crystal. ecent evidence suggests that the Hope dia- The recent discovery of a lead cast of the French mond was cut in the late 18th or early 19th Blue at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle Rcentury from the French Blue diamond, (MNHN) in Paris has provided more accurate infor- which itself was cut in the 1670s from the mation concerning the physical attributes of that dia- Tavernier Blue (see, e.g., Attaway, 2005; Farges et mond. Farges et al. (2008, 2009) created an updated al., 2008, 2009). Yet the only documentation of the computer model from a laser scan of the lead cast. -

Mineralogical Evidence for Partial Melting and Melt-Rock Interaction Processes in the Mantle Peridotites of Edessa Ophiolite (North Greece)

minerals Article Mineralogical Evidence for Partial Melting and Melt-Rock Interaction Processes in the Mantle Peridotites of Edessa Ophiolite (North Greece) Aikaterini Rogkala 1,* , Petros Petrounias 1 , Basilios Tsikouras 2 , Panagiota P. Giannakopoulou 1 and Konstantin Hatzipanagiotou 1 1 Section of Earth Materials, Department of Geology, University of Patras, 265 04 Patras, Greece; [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (P.P.G.); [email protected] (K.H.) 2 Physical and Geological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Jalan Tungku Link, Gadong BE1410, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2610996288 Received: 10 December 2018; Accepted: 14 February 2019; Published: 17 February 2019 Abstract: The Edessa ophiolite complex of northern Greece consists of remnants of oceanic lithosphere emplaced during the Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous onto the Palaeozoic-Mesozoic continental margin of Eurasia. This study presents new data on mineral compositions of mantle peridotites from this ophiolite, especially serpentinised harzburgite and minor lherzolite. Lherzolite formed by low to moderate degrees of partial melting and subsequent melt-rock reaction in an oceanic spreading setting. On the other hand, refractory harzburgite formed by high degrees of partial melting in a supra-subduction zone (SSZ) setting. These SSZ mantle peridotites contain Cr-rich spinel residual after partial melting of more fertile (abyssal) lherzolite with Al-rich spinel. Chromite with Cr# > 60 in harzburgite resulted from chemical modification of residual Cr-spinel and, along with the presence of euhedral chromite, is indicative of late melt-peridotite interaction in the mantle wedge. Mineral compositions suggest that the Edessa oceanic mantle evolved from a typical mid-ocean ridge (MOR) oceanic basin to the mantle wedge of a SSZ.