Downloaded From: Publisher: Intellect DOI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lush's Final Show @ Manchester Academy

LUSH’S FINAL SHOW @ MANCHESTER ACADEMY larecord.com /photos/2016/11/26/lushs-final-show-manchester-academy November 26th, 2016 | Photos Photos by Todd Nakamine 2016 brought a very successful return for Lush with sold out shows, festival appearances and a new EP Blind Spot. But 2016 also brought the final show the band would play at the Manchester Academy to a somewhat somber crowd. We were soaking in every last note all knowing this was the last show ever (sometimes knowing is worse). Kicking off their high energy set with “De-luxe” and plowing through classic after classic covering their entire career including “Kiss Chase,” “Thoughtforms,” “Etheriel,” “Light From A Dead Star,” “Hypocrite,” “Undertow” plus the new already classic Lush track “Out of Control.” While nothing can replace the late Chris Acland’s subtleties that helped define Lush’s sound, drummer Justin Welsh’s hard and fast style of playing added an extra kick apparent in songs like “Ladykiller,” or as Miki Berenyi said should be renamed “Pussygrabber” in light of U.S.A.’s new president elect, as well as “Sweetness and Light.” Acland’s close friend Michael Conroy of Modern English filled in on bass as Phil King left the band in October. Finishing with the final song of the night “Monochrome,” Emma Anderson, Berenyi and Welsh gave their last waves, left the stage for the final time and the crowd quietly shuffled out having been treated with a very special goodbye. Kicking off the night was Brix & The Extricated featuring post punk legends Brix Smith, Steve Hanley and Paul Hanley (The Fall). -

Kick out the Cool Greenhouse Feb 19 2021

Cool Greenhouse w/Kick Out The James Feb 14 2021 www.artguy.com/KOTJ.html www.mixcloud.com/KOTJames The Cool Greenhouse - The End of The World London/The End of the World The Cool Greenhouse - I’m Into C.B. (Fall Cover) RIP Smitty Single The Cool Greenhouse - London London/The End of the World Single The Male Nurse - My Own Private Patrick Swayze The Cool Greenhouse - Life Advice The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - Cardboard Man The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - Dirty Glasses The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - Alexa Single The Desperate Bicycles - Don't Back the Front B-Side to The Medium Was Tedium Wild Billy Childish & The Musicians Of The British Empire - Snack Crack b/w Elvis Presley Is Dead OOPS/ D’oh! The Cool Greenhouse - Dirty Glasses The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - 4Chan The Velvet Underground - There She Goes The Velvet Underground and Nico The Modern Lovers - Pablo Picasso The Cool Greenhouse - Smile, Love The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - Outlines The Cool Greenhouse (album) Greater Than One - Why Do Men Have Nipples? G-Force The Cool Greenhouse - Trojan Horse The Cool Greenhouse (album) Dry Cleaning - Strong Feelings New Long Leg Black Midi - bmbmbm Schlagenheim Uranium Club - Definitely Infrared Radiation Suit The Cosmo Cleaners The Fall - Winter 2 Hex Enduction Hour The Fall - Words of Expectation (Live Peel Session) The Fall - The NWRA Grotesque (After The Gramme) The Fall - Your Heart Out Dragnet The Fall - Fiery Jack Totale's Turns (It's Now Or Never). -

Experimental Sound & Radio

,!7IA2G2-hdbdaa!:t;K;k;K;k Art weiss, making and criticism have focused experimental mainly on the visual media. This book, which orig- inally appeared as a special issue of TDR/The Drama Review, explores the myriad aesthetic, cultural, and experi- editor mental possibilities of radiophony and sound art. Taking the approach that there is no single entity that constitutes “radio,” but rather a multitude of radios, the essays explore various aspects of its apparatus, practice, forms, and utopias. The approaches include historical, 0-262-73130-4 Jean Wilcox jacket design by political, popular cultural, archeological, semiotic, and feminist. Topics include the formal properties of radiophony, the disembodiment of the radiophonic voice, aesthetic implications of psychopathology, gender differences in broad- experimental sound and radio cast musical voices and in narrative radio, erotic fantasy, and radio as an http://mitpress.mit.edu Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142 Massachusetts Institute of Technology The MIT Press electronic memento mori. The book includes new pieces by Allen S. Weiss and on the origins of sound recording, by Brandon LaBelle on contemporary Japanese noise music, and by Fred Moten on the ideology and aesthetics of jazz. Allen S. Weiss is a member of the Performance Studies and Cinema Studies Faculties at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. TDR Books Richard Schechner, series editor experimental edited by allen s. weiss #583606 5/17/01 and edited edited by allen s. weiss Experimental Sound & Radio TDR Books Richard Schechner, series editor Puppets, Masks, and Performing Objects, edited by John Bell Experimental Sound & Radio, edited by Allen S. -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00 -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

(2020) Mark E. Smith, Brexit Britain and the Aesthetics and Politics of the Working Class Weird

Wilkinson, David (2020) Mark E. Smith, Brexit Britain and the Aesthetics and Politics of the Working Class Weird. Open Library of Humanities. ISSN 2056- 6700 Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/624332/ Version: Published Version Publisher: Open Library of Humanities DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.535 Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk The Working-Class Avant-Garde How to Cite: Wilkinson, D 2020 Mark E. Smith, Brexit Britain and the Aesthetics and Politics of the Working Class Weird. Open Library of Humanities, 6(2): 11, pp. 1–26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.535 Published: 09 September 2020 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of Open Library of Humanities, which is a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Open Library of Humanities is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. David Wilkinson, ‘‘Mark E. Smith, Brexit Britain and the Aesthetics and Politics of the Working Class Weird’ (2020) 6(2): 11 Open Library of Humanities. DOI: https://doi. -

Guardian and Observer Editorial

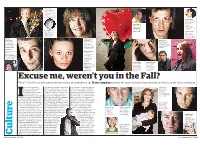

≤ Steve Davies Drums/congas, 1980 Now: does music workshops in schools and prisons ‘I refused to tour with a rock band ever again’ ≤ Kay Carroll Backing vocals/man- agement, 1977-83 ≤ Now: doctor’s Dave Milner assistant Drums, 2001-04 ‘Mark never let Now: taxi driver anybody feel part ‘The Fall is the of the Fall’ ≤ band to be in if you Una Baines desire extremes’ Keyboards, 1976-78 ≤ Simon Archer Now: singer Bass, 2003-04 ‘Mark is certainly Now: musician not just an ogre’ ‘All the stories and myths about Mark ≤ ≥ Simon Julia Adamson were true’ Wolstencroft (then Nagle) ≥ Ruth Daniel Drums, 1986-97 Keyboards/guitar, Keyboards, 2002 Now: musician 1995-2001 Now: researcher/ ‘I learned so much Now: works at a record label manager about life, just publishing company ‘Mark would bark listening to Mark’ ‘I was quite poorly like a dog’ after dating Mark’ ≤ Ed Blaney Guitar/tour manager, ≤ Karen Leatham 2000-04 Bass, 1988 Now: ‘free man’ Now: Designer/carer ‘My duties included ‘Looking after keeping ex-members gentlemen with out of the dressing mental needs is room’ not unlike being in a band’ ≤ Dave Tucker ≥ Tommy Crooks ≥ Brix Smith Clarinet, 1980-81 Guitar, 1997-98 Guitar, 1983-89, 94-96 Now: musician Now: artist Now: runs a boutique ‘Mark brought in ‘The Fall are the ‘Mark fired a people like me to best British band soundman for make the other ever, including Excuse me, weren’teating a salad’ yyou in theguys nervous’ Fall?the Beatles’ Mark E Smith’s band is legendary for its ever-changing line-up. -

HALE*S Connecticut Thereby I’Ncreasihg' Their Vjews Frankly and Unequlvo- Ing the Two Years Remaining in His Enslaye the 'Orient.” ' , Term

• V-. ’ ■'I •' » *• . MOKDAY. JANUARY^ 7, 1987 ATcrtKc DaHy Nat Pr«M Run Tha WaaHitr. ' Por the $Ve^ Ended Feiaeaat « f IT. S. W entlm BcrMUi Jannary 5, 1467 3,600 Fair, colder tonight. Low, 10 td. t r i f l e ^ Pledged 12,328 IS. Wedneaday rhance of occsmAosi- Member of the Alidlt al' light snow daMng the day. Higll IVfMH Campaign Rurentt of Cirrulation in mid 80s. By Screw Firm WATKINI , Hanche$ter-~~A CHy o/ VUlagt^ Charm "A contribution of $3,600 to. -WEST VOL. LXXVI, NO. 8,1 (FOURTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY. JA>^UARY 8, 1957 . 4, (Clbaallled Adrertiataig on P ig * U ) PRICE FIVE CENTS Mancheater Memorial Hdapital'a! $1,470,000 ftuilding fund eampaign i FHatral Ssni has .been pledged by the Hartford j Machine Screw Co.* division of| Onhand J. West, Dii|i«ter 141^ East Center ! East Reich Standai'd Screw Co, ^ ^ AOteheU 9-71M Ashed to comment concerning; • • ' - • the 'contribution. James A, Ta.vlor, j Gets President • of ‘ the company said, • "Hartford Machine'. Screw Co. has 1 Maneheater’a OldOM ion^ recognised that part of their j with Fineat F aclU lm corporate responsibility is to see Tax Extension Off-Street ParUngj Soviet A id that proper hospital, facilities are I Eatabtiahed 1874% provided fo r its einpIo>’es in the ' Washington, Jan. 8 (/P),—- be two or three weeks before joint Moscow. Jan; 8 </P)— The ij commiinitiea in which they live., 'j hearings planned by the Senate Soviet., Union has promised Sidney Ellis, chairman of ~the President Eisenhow'er and Re Foreign Relations s,and ' Armed ! fund's corporation committee comr publican Congressional lead- Services committees gre com-i Communist East Germany mented that the Hartford Machine era formally dwiddd today to pleted. -

Page 1 of 163 Music

Music Psychedelic Navigator 1 Acid Mother Guru Guru 1.Stonerrock Socks (10:49) 2.Bayangobi (20:24) 3.For Bunka-San (2:18) 4.Psychedelic Navigator (19:49) 5.Bo Diddley (8:41) IAO Chant from the Cosmic Inferno 2 Acid Mothers Temple 1.IAO Chant From The Cosmic Inferno (51:24) Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo 3 Acid Mothers Temple 1.Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (1:05:15) Absolutely Freak Out (Zap Your Mind!) 4 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.Star Child vs Third Bad Stone (3:49) 2.Supernal Infinite Space - Waikiki Easy Meat (19:09) 3.Grapefruit March - Virgin UFO – Let's Have A Ball - Pagan Nova (20:19) 4.Stone Stoner (16:32) 1.The Incipient Light Of The Echoes (12:15) 2.Magic Aum Rock - Mercurical Megatronic Meninx (7:39) 3.Children Of The Drab - Surfin' Paris Texas - Virgin UFO Feedback (24:35) 4.The Kiss That Took A Trip - Magic Aum Rock Again - Love Is Overborne - Fly High (19:25) Electric Heavyland 5 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.Atomic Rotary Grinding God (15:43) 2.Loved And Confused (17:02) 3.Phantom Of Galactic Magnum (18:58) In C 6 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.In C (20:32) 2.In E (16:31) 3.In D (19:47) Page 1 of 163 Music Last Chance Disco 7 Acoustic Ladyland 1.Iggy (1:56) 9.Thing (2:39) 2.Om Konz (5:50) 10.Of You (4:39) 3.Deckchair (4:06) 11.Nico (4:42) 4.Remember (5:45) 5.Perfect Bitch (1:58) 6.Ludwig Van Ramone (4:38) 7.High Heel Blues (2:02) 8.Trial And Error (4:47) Last 8 Agitation Free 1.Soundpool (5:54) 2.Laila II (16:58) 3.Looping IV (22:43) Malesch 9 Agitation Free 1.You Play For -

The Fall, "The Frenz Experiment"

Brainwashed - The Fall, "The Frenz Experiment" Written by Eve McGivern Sunday, 18 October 2020 00:00 - Last Updated Sunday, 18 October 2020 11:12 There are three main periods The Fall may be grouped into: the raw punk early years, the more “melodious” classic years, and the post-'90s period up to Mark E. Smith’s passing in 2018. The Frenz Experiment , originally released in 1988 and reissued this year by Beggars Banquet, is part of the “classic” years, a time when the band churned out a series of nearly perfect albums. Beggars Banquet I came upon The Fall in 1987 by way of the compilation of early singles Palace of Swords Reversed . I remember not being entirely sure what to make of them, but loved “Totally Wired.” In those days, I got most of my music from college radio and MTV’s 120 Minutes , so unless either were spinning The Fall, I had so much other music vying for my attention. When lo and behold, the band had themselves a bonafide radio hit with “Hit the North (Part 1),” a funky, groovy little number that, what’s this? — was danceable? The wonderful and frightening world of The Fall was suddenly opened to myself and so many others. Additionally, along came a lovely rendition of The Kinks’ “Victoria” that saw airplay on MTV, and the band started to have greater access to the American psyche. It was the album in which I fell in love with The Fall, and became a lifelong listener (as well as a glutton for punishment in attempting to obtain their entire catalog). -

Smash Hits Volume 65

35pUSA$i75 Mayas- June 101 ^ S */A -sen ^^ 15 HIT UfRiasmolding StandAndDe^^r iMimnliMl Being Wj LANDSCAPBin colour KIM WILDE m u ) Vol. 3 No. 11 IF YOU'VE already sneaked a peek around the back of this issue you'll have twigged the fact that you're dealing with something out of the ordinary. So welcome, friends, to the first (and the only?) double sided edition of your favourite musical publication. In effect you get two magazines, each with its own cover, bumper feature, songwords, competition and Bitz section. Soon as you get fed up of poring over this half, just flip it and play the other side. Now you may well ask why we've taken the unusual step of standing the entire magazine on its head. Well, there are a number of reasons; 1 To confuse newsagents 2) We couldn't decide who to put on the cover In 3) the hope that some dummies would buy it twice 4) For laffs THIS SIDE STAND AND DELIVER Adam And The Ants 2A NORMAN BATES Landscape .8A DON'T LET IT PASS YOU BY UB40 9A ROCKABILLY GUY Polecats 9A GHOSTS OF PRINCES IN TOWERS Rich Kids 11A IS THAT LOVE Squeeze 14A BETTE DAVIS EYES Kim Games 14A BEING Vi/ITH YOU Smokey Robinson 17A HOW 'BOUT US Champaign 19A STRAY CATS: Feature 4A/5A/6A BITZ (A) 12A/13A CARTOON 17A DISCO ISA STAR TEASER 20A THE BEAT COMPETITION 21A SINGLES REVIEWS 23A LANDSCAPE: Colour Poster The Middle THAT SIDE FUNERAL PYRE The Jam 2B HOUSES IN MOTION Talking Heads 8B THE ART OF PARTIES Japan SB BAD REPUTATION Thin Lizzy SB THEM BELLY FULL (BUT WE HUNGRY) Bob Marley 11B ANGEL OFTh£ MORNING Juice Newton 14B KIM WILDE: Feature 4B/5B/6B BITZ(B) 12B/13B UNDERTONES COMPETITION 15B LEHERS 16B/17B INDEPENDENT BITZ 1SB GIGZ 20B/21B ALBUM REVIEWS 23B The charts appearing in Smash Hits are compiled by Record Business Research from information supplied by panels of specialist shcps.