1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project JOHN W. MCDONALD Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: June 5, 1997 Copyright 2 3 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Ko lenz, Germany of U.S. military parents Raised in military bases throughout U.S. University of Illinois Berlin, Germany - OMGUS - Intern Program 1,4.-1,50 1a2 Committee of Allied Control Council Morgenthau Plan Court system Environment Currency reform Berlin Document Center Transition to State Department Allied High Commission Bonn, Germany - Allied High Commission - Secretariat 1,50-1,52 The French Office of Special Representative for Europe General 6illiam Draper Paris, France - Office of the Special Representative for Europe - Staff Secretary 1,52-1,54 U.S. Regional Organization 7USRO8 Cohn and Schine McCarthyism State Department - Staff Secretariat - Glo al Briefing Officer 1,54-1,55 Her ert Hoover, 9r. 9ohn Foster Dulles International Cooperation Administration 1,55-1,5, E:ecutive Secretary to the Administration Glo al development Area recipients P1480 Point Four programs Anti-communism Africa e:perts African e:-colonies The French 1and Grant College Program Ankara, Turkey -CENTO - U.S. Economic Coordinator 1,5,-1,63 Cooperation programs National tensions Environment Shah of Iran AID program Micro2ave projects Country mem ers Cairo, Egypt - Economic Officer 1,63-1,66 Nasser AID program Soviets Environment Surveillance P1480 agreement As2an Dam Family planning United Ara ic Repu lic 7UAR8 National -

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

Harlan Cleveland Interviewer: Sheldon Stern Date of Interview: November 30, 1978 Location: Cambridge, Massachusetts Length: 56 Pages

Harlan Cleveland Oral History Interview—11/30/1978 Administrative Information Creator: Harlan Cleveland Interviewer: Sheldon Stern Date of Interview: November 30, 1978 Location: Cambridge, Massachusetts Length: 56 pages Biographical Note Cleveland, Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs (1961- 1965) and Ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (1965-1969), discusses the relationship between John F. Kennedy, Adlai E. Stevenson, and Dean Rusk; Stevenson’s role as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations; the Bay of Pigs invasion; the Cuban missile crisis; and the Vietnam War, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed February 21, 1990, copyright of these materials has passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Collection: Vertical File, Ronald Reagan Library Folder Title: Reagan, Ronald W

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Vertical File, Ronald Reagan Library Folder Title: Reagan, Ronald W. – Promises Made, Promises Kept To see more digitized collections visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digitized-textual-material To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/white-house-inventories Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/research- support/citation-guide National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ . : ·~ C.. -~ ) j/ > ji· -·~- ·•. .. TI I i ' ' The Reagan Administration: PROMISES MADE PROMISES KEPI . ' i), 1981 1989 December, 1988 The \\, hile Hollst'. Offuof . Affairs \l.bshm on. oc '11)500 TABIE OF CDNTENTS Introduction 2 Economy 6 tax cuts 7 tax reform 8 controlling Government spending 8 deficit reduction 10 ◄ deregulation 11 competitiveness 11 record exports 11 trade policy 12 ~ record expansion 12 ~ declining poverty 13 1 reduced interest rates 13 I I I slashed inflation 13 ' job creation 14 1 minority/wmen's economic progress 14 quality jobs 14 family/personal income 14 home ownership 15 Misery Index 15 The Domestic Agenda 16 the needy 17 education reform 18 health care 19 crime and the judiciary 20 ,,c/. / ;,, drugs ·12_ .v family and traditional values 23 civil rights 24 equity for women 25 environment 26 energy supply 28 transportation 29 immigration reform 30 -

The Foreign Service Journal, July 1975

FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL JULY 1975 60 CENTS isn I The diplomatic | way to save. ■ All of these outstanding Ford-built cars are available to you at special diplomatic discount savings. ■ Delivery will be arranged for you either stateside or ■ overseas. And you can have the car built to Export* or Domestic specifications. So place your order now for diplomatic savings on the cars for diplomats. For more information, contact a Ford Diplomatic Sales Office. Please send me full information on using my diplomatic discount to purchase a new WRITE TO: DIPLOMATIC SALES: FORD MOTOR COMPANY 815 Connecticut Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006/Tel: (202) 785-6047 NAME ADDRESS CITY STATE/COUNTRY ZIP Cannot be driven in the U.S American Foreign Service Association Officers and Members of the Governing Board THOMAS D. BOY ATT, President F. ALLEN HARRIS, Vice President JOHN PATTERSON, Second Vice President RAYMOND F. SMITH, Secretary JULIET C. ANTUNES, Treasurer CHARLOTTE CROMER & ROY A. HARRELL, JR., AID Representatives FRANCINE BOWMAN, RICHARD B. FINN, CHARLES O. HOFFMAN & FRANCIS J. McNEIL, III State Representatives STANLEY A. ZUCKERMAN, USIA Representative FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL JAMES W. RIDDLEBERGER & WILLIAM 0. BOSWELL, Retired Representatives JULY 1975: Volume 52, No. 7 Journal Editorial Board RALPH STUART SMITH, Chairman G. RICHARD MONSEN, Vice Chairman FREDERICK QUINN JOEL M. WOLDMAN EDWARD M. COHEN .JAMES F. O'CONNOR SANDRA L. VOGELGESANG Staff RICHARD L. WILLIAMSON, Executive Director DONALD L. FIELD, JR.. Counselor HELEN VOGEL, Committee Coordinator CECIL B. SANNER, Membership and Circulation Communication re: Excess Baggage 4 Foreign Service Educational AUDINE STIER and Counseling Center MARY JANE BROWN & Petrolimericks 7 CLARKE SLADE, Counselors BASIL WENTWORTH Foreign Policy Making in a New Era: Journal SHIRLEY R. -

March 9, 1981 Dear Paul: Thanks for Sending on the Information

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON March 9, 1981 Dear Paul: Thanks for sending on the information relative to the Senate race in California. It looks to me to be developing into a very interesting primary. Thanks for keeping me posted on your activities .. Warm regards, MICHAEL K. DEAVER Assistant to the President Deputy Chief of Staff The Honorable Paul McCloskey, Jr. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 PAUL N. McCLOSKEY, JR. 205 ~ Bu!LDIN<I 12TH DISTRICT, CAL.ll"ORNIA WASHINGTON, D.C. 20515 (202) 225-5411 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS DISTRICT OFFICE: 305 GRANT AVENUE AND Congrt!>!> of tbt Wnittb ~tatt~ PALO ALTO, CALIFORNIA COMMITTEE ON 9~308 MERCHANT MARINE (415) 326-7383 AND FISHERIES }!}ou~t of l\epresentatibtS lla.ubington, 19.«:. 20515 February 17, 1981 Michael K. Deaver Assistant to the President Deputy Chief of Staff The White House Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mike: Charles Wallen passed on a suggestion from the President that I contact you about my Senate candidacy. Naturally, I would be pleased to have whatever advice and cooperation that you and the President's staff can provide, but I will fully understand that whatever action you take will be based on your perception of what is in the nation's best interest. I would like to think I can be a much better Senator than Sam Hayakawa, Barry Goldwater, Jr., or the President's daughter, but, most importantly, I think I can give you better assurance of defeating Jerry Brown and retaining the seat in Republican hands than any of the other candidates. -

County Delays Decision on Ban of Paraphernalia

One Section, 12 Pages Vol. 61 No. 35 University of California. Santa Barbara Tuesdùy, November 4,1980 County Delays Decision On Ban of Paraphernalia By JEFF LESHAY Due to an amendment added to putting down free enterprise,” he Nexus Staff Writer the ordinance at yesterday’s board continued. The County Board of Supervisors meeting, an amendment stating John Ferriter, an Associated voted 4-1 yesterday in favor of a that punishment imposed upon a Students representative from drug paraphernalia ordinance violator of the drug paraphernalia UCSB, told the supervisors, “ You introduced on Oct. 27 designed to law will, in fact, be no more severe must vote your constituency, not ban completely the sale of drug than citations or $100 fines imposed your own minds,” emphasizing paraphernalia in Santa Barbara for possession of an ounce or less of that the majority of the con County. marijuana, the final hearing and stituency may well be opposed to Currently, state law prohibits voting on whether or not to enact the ordinance. “ What you’re the sale of “ paraphernalia that is the ordinance into law will occur voting on is a matter of freedom of designed for the smoking of during next Monday’s meeting. personal choice,” he said. “ No one tobacco, products prepared from Lengthy discussion on the is forced to buy drug parapher tobacco, or any controlled sub subject, however, did take place nalia — it is a matter of conscious stance” to anyone under 18. The yesterday amongst members of choice.” law mandates that drug the board and a number of Ronald Stevens, an attorney paraphernalia be kept in a speakers from the floor representing Concerned Citizens of separate room in any place of representing various aspects of the Santa Barbara, and Pat Morrow, a business where it is sold, and that community. -

107Th Congress

1 ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ! CONVENED JANUARY 3, 2001 FIRST SESSION ADJOURNED DEC. 20, 2001 SECOND SESSION ! CONVENED JANUARY 23, 2002 ADJOURNED NOVEMBER 22, 2002 CALENDARS OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND HISTORY OF LEGISLATION FINAL EDITION PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF JEFF TRANDAHL, CLERK OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES: By the Office of Legislative Operations The Clerk shall cause the calendars of the House to be printed Index to the Calendars will be printed the first legislative day and distributed each legislative day. Rule II, clause 2(e) of each week the House is in session U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 2003 19–038 VerDate Jan 31 2003 10:01 Apr 11, 2003 Jkt 019006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5850 Sfmt 5850 E:\HR\NSET\FINAL2.CAL FINAL2 2 SPECIAL ORDERS SPECIAL ORDER The format for recognition for morning-hour debate and restricted special order speeches, SPEECHES which began on February 23, 1994, was reiterated on January 4, 1995, and was supplemented on January 3, 2001, will continue to apply in the 107th Congress as outlined below: On Tuesdays, following legislative business, the Chair may recognize Members for special-order speeches up to midnight, and such speeches may not extend beyond midnight. On all other days of the week, the Chair may recognize Members for special-order speeches up to four hours after the conclusion of five-minute special- order speeches. Such speeches may not extend beyond the four-hour limit without the permission of the Chair, which may be granted only with advance consultation between the leaderships and notification to the House. -

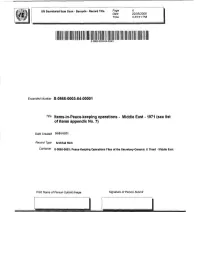

Middle East -1971 (See List of Items Appendix No. 7)

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 4 Date 22/05/2006 Time 4:43:51 PM S-0865-0003-04-00001 Expanded Number S-0865-0003-04-00001 Title items-in-Peace-keeping operations - Middle East -1971 (see list of items appendix No. 7) Date Created 01/01/1971 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0865-0003: Peace-Keeping Operations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant - Middle East Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit x/, 7 Selected Confidential Reports on OA-6-1 - Middle East 1971 Cable for SG from Goda Meir - 1 January 1971 2 Notes on meeting - 4 January 1971 - Present: SG, Sec. of State Rogers, 0 Ambassador Charles Yost, Mr. Joseph Sisco, Mr. McClosky and Mr. Urquhart t 3) Middle East Discussions - 5 January 1971 - Present: Ambassador Tekoah Mr. Aphek, Ambassador Jarring, Mr. Berendsen 4 Letter from Gunnar Jarrint to Abba Eban - 6 January 1971 x i Letter to Gunnar Jarring from C.T. Crowe (UK) 6 January 1971 *6 Notes on meeting - 7 January 1971 - Present: SG, Sir Colin Crowe 7 Notes on meeting - 7 January 1971 - Present: SG, Mr. Yosef Tekoah 8 "Essentials of Peace"(Israel and the UAR) - 9 January 1971 9 "Essentials of Peace" (Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordon - 9 January 1971 Statement by El Tayalt - 13 January 1971 Minutes of meeting - 13 January 1971 - Present: M. Masmoudi, El-Goulli, Mr. Fourati, Mr. Jarring, Mr. Berendsen^ Letter from William P. Rogers - 15 January 1971 Letter - Middle East - 15 January 1971 Implementation of Security Council Resolution 242 of 22 November 1967 For The Establishment of a Just and Lasting Peace in the Middle East - 18 January 1971 C H-^-^ ?-«-r-"~) Comparison of the papers of Israel and the United Arab Republic 18 January 1971 L " Notes on meeting - 19 January 1971 - Present: SG, Ambassador Yost, USSR - 1 January 1971 - Middle East Communication from the Government of Israel to the United Arab Republic through Ambassador Jarring - 27 January 1971 France - 27 January 1971 - Middle East Statement by Malik Y.A. -

Harlan Cleveland Interviewed by Warren Nishimoto (1996) Narrative Edited by Hunter Mcewan and Warren Nishimoto

College of Education v University of Hawai‘i at Mänoa 43 Harlan Cleveland Interviewed by Warren Nishimoto (1996) Narrative edited by Hunter McEwan and Warren Nishimoto Harlan Cleveland, political scientist, diplomat, public execu- tive, author of dozens of articles and books, and eighth presi- dent of the University of Hawai‘i, was born in 1918 in New York City. He was the son of Stanley Matthews Cleveland and Marian Phelps Van Buren Cleveland. His father, an Episcopal chaplain, died prematurely in 192. Nursing his father during a long illness had taken a toll on Cleveland’s mother, and the family was recommended to move to a warmer climate. She took Harlan and his siblings to southern Europe where she had spent a part of her childhood—first to the Basse Pyrénées region of France and later to Geneva in Switzerland. Harlan Cleveland’s schooling there gave him a strong foundation in French, and he also picked up some Italian and German. In 191, the family returned to the United States. Cleve- land attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. There, he learned to value the connections between the disci- plines, laying the grounds for his later abilities as a generalist: (UH Photo Archives) “I was always struck with the contrast between a situation in a school or college or university, where all the organization and who had escaped before the outbreak of hostilities. Their job all the power structure, too, is built on disciplines—and the was to determine how to destroy selective pieces of the Ital- communities surrounding it, where everything is organized by ian economy, in some cases by advising the U.S. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that.