Ordisk Useologi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St Periodic Report Hypatia

D1.2 1st Periodic report Hypatia 1ST PERIODIC REPORT HYPATIA Work package WP1 number: Report number: 1 Contributors: Aliki Giannakopoulou, Meie van Laar Institutions: NEMO SCIENCE MUSEUM Revision Date: 25/07/2016 Status: Final 1 D1.2 1st Periodic report Hypatia Table of Contents SUMMARY 3 WORK PROGRESS- GENERAL OVERVIEW 4 WORK PROGRESS- DIVIDED IN WORK PACKAGES 6 WP1 – MANAGEMENT 6 OBJECTIVES AND MILESTONES 6 PROGRESS TOWARDS OBJECTIVES– TASKS COMPLETED/ISSUES RAISED 6 DELIVERABLES SUBMITTED 11 WP2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 11 OBJECTIVES AND MILESTONES 11 PROGRESS TOWARDS OBJECTIVES– TASKS COMPLETED/ISSUES RAISED 11 DELIVERABLES SUBMITTED 13 WP3 HUB COORDINATION AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 14 OBJECTIVES AND MILESTONES 14 PROGRESS TOWARDS OBJECTIVES– TASKS COMPLETED/ISSUES RAISED 14 DELIVERABLES SUBMITTED 19 WP4 TOOLKIT DEVELOPMENT 19 OBJECTIVES AND MILESTONES 19 PROGRESS TOWARDS OBJECTIVES– TASKS COMPLETED/ISSUES RAISED 20 DELIVERABLES SUBMITTED 22 WP5 TOOLKIT IMPLEMENTATION 22 OBJECTIVES AND MILESTONES 22 PROGRESS TOWARDS OBJECTIVES– TASKS COMPLETED/ISSUES RAISED 22 DELIVERABLES SUBMITTED 22 WP6 DISSEMINATION 22 OBJECTIVES AND MILESTONES 22 PROGRESS TOWARDS OBJECTIVES– TASKS COMPLETED/ISSUES RAISED 23 DELIVERABLES SUBMITTED 31 WP7 ETHICS REQUIREMENTS 31 OBJECTIVES AND MILESTONES 31 DELIVERABLES SUBMITTED 31 DELIVERABLES OVERVIEW 32 MILESTONES OVERVIEW 33 USE OF RESOURCES 33 OVERVIEW OF ELIGIBLE COSTS 33 OVERVIEW OF PROGRESS PER WP 34 2 D1.2 1st Periodic report Hypatia Summary The Hypatia project was launched on August 1st. Hypatia addresses the challenge of bringing more teenagers into STEM related careers. The project aims to communicate sciences to young people in a more gender inclusive way. In order to achieve this we are involving schools, industry, science centres and museums, policy makers and teenagers directly. -

SEUPHOR Michel

SEUPHOR Michel. "La Sculpture de ce Siècle." Dictionnaire de la Sculpture Moderne Éditions du Griffon / 1959 / Neuchâtel / Suisse INDEX A Achiam, Israël Adam, Henri-Georges Adam-Tessier, Maxime Adams, Robert Aeschbacher, Hans Agam, Jacob Althabe, Julian Amsterdam Anderson, Jéremy Andréou, Constantin Andriessen, Mari Silvester Animisme Annenko Georges Anthoons Willy Anton Victor Apollinaire, Guillaume Arbus, André Archipenko, Alexandre Architecture et Sculpture Arden Quin, Carmelo Arensberg Armitage, Kenneth Armory Show Arnhem Arnold, Anne Arp, Jean Art Brut Artigas, Llorens Auricoste, Emmanuel Avignon Avramidis, Joannis Azpiazu, José Ramon B Badii, Libéro Baenninger, Otto-Charles Bakic, Vojin Bakis, Josuas Bâle Barcelone Balach, Ernst Bauhaus Baum, Otto Baumester, Willi Beaudin, André Beethoven Bekman, Hubert Belling, Rudolph Béothy, Etienne Berlin Berne Bernheim jeune Bertoïa, Harry Bertoni, Wander Beslic, Anna Biederman, Charles Bilger, Maria Bill, Max Blasco Ferrer, Eleuterio Blaszko, Martin Blaue Reiter Bloc, André Boadella, Francisco Boccioni, Umberto Bodmer, Walter Boileau, Martine Boisecq, Simone Boudin, Eugène-Louis Bourdelle, Antoine Bourek, Zlato Bourgeois, Louise Brancusi, Constantin Braque, Georges Breetvelt, Adolf Breton, André Brignoni, Serge British Council Brummer (Galerie) Bruxelles Buchholz, Erich Bufano, BenjaminoBenvenuto Burckardt, Carl Burla, Johannes Burri, Alberto Bury, Paul Butler, Reg C Cahn,Marcelle Caille, Pierre Cairoli, Carlos Calder, Alexandre Callery,Mary Calo, Aldo Calvin, Albert Cannilla, Franco Canova, -

Pårup Kirke Odense Herred

2647 Fig. 1. Kirken set fra øst med stendiget som hegner den ældste del af kirkegården. Foto David Burmeister Kaaring 2012. – The church seen from the east with the stone wall enclosing the oldest part of the churchyard. PÅRUP KIRKE ODENSE HERRED Indledning. Pårup Kirke er tidligst omtalt 1339, da Fyns Kirken lå til Gråbrødre Hospital indtil 1816, da den biskop, Peder Pagh, med ‘patronatsejernes samtykke’ udskiltes og efterfølgende blev et selvstændigt pastorat, inkorporerede den i Odense Skt. Knuds Kloster, med men i øvrigt fortsat ejedes af hospitalet.4 Under Tre- henblik på at understøtte de klosterbrødre, der stude- årskrigen 1848-50 benyttedes kirken midlertidigt til rede i Frankrig (jf. også s. 77).1 I samme forbindelse opmagasinering af krudttønder.5 omtales kirkens indvielse til Vor Frue (værnehelgen). Dette forhold ændredes efter reformationen, da Pårup Kirke 1566 blev lagt til Gråbrødre Hospital, hvis for- Kirken ligger nordligt i den oprindelige landsby, stander tilkendtes kronens part af Pårup Kirkes tiende der i 1900-tallet er udvidet med betydelige par- mod at tilskikke en ‘duelig sognepræst’, der ligeledes celhuskvarterer mod nord, således at kirken og skulle betjene hospitalets beboere (jf. s. 1559).2 kirkegården nu befinder sig i selve skellet mellem Efter synet 1723 blev en omfattende restaurering Odenses sammenvoksede nordvestlige forstæder iværksat på Gråbrødre Hospitals ordre. Denne omfat- tede såvel kirkebygningen, klokkestol og stolestader og de opdyrkede arealer vest for byen. Bygningen som kirkegården, hvis mur og låger blev repareret og er rejst på en lille forhøjning, der særligt øst for porten helt fornyet.3 kirken falder ganske stejlt. I kraft af denne hæve- 167* 2648 ODENSE HERRED Fig. -

List of Participants

List of Participants SURNAME FIRST NAME Country SURNAME FIRST NAME Country AALBERGSJØ SIV G. Norway AMON HEIDEMARIE Austria ABRAHAMS IAN United Kingdom AMOS RUTH United Kingdom ABRAHAMSSON CRISTIAN Sweden AMPATZIDIS GEORGIOS Greece ABRAMOVICH ANAT Israel AMPRAZIS ALEXANDROS Greece ABRIL-GALLEGO ANA MARÍA Spain ANASTÁCIO ZÉLIA Portugal ACEBAL EXPOSITO MARIA DEL CARMEN Spain ANDERSEN TRINE HØJBERG Norway ACHIAM MARIANNE Denmark ANDERSON DAYLE New Zealand ACOSTA GARCIA KATHERINE Chile ANDERSON TREVOR United States ACUNA CLAUDIA Netherlands ANDERSSON JAN Sweden ADADAN EMINE Turkey ANDERSSON KRISTINA Sweden ADAMS JENNIFER Canada ANDRÉE MARIA Sweden ADBO KARINA Sweden ANJOU CLAIRE France ADÚRIZ-BRAVO AGUSTÍN Argentina ANTINK-MEYER ALLISON United States AGADI DINA Israel ANWAR TASNEEM Pakistan AGEN FEDERICO Spain ARANDA GEORGE Australia AGUIRRE-MUNOZ ZENAIDA United States ARAUJO CARLA Brazil ÅHMAN NICLAS Sweden ARAUJO CASTRO PABLO MICAEL Brazil AHRENKIEL LINDA Denmark ARCHER LOUISE United Kingdom AHUMADA GERMAN Chile ARNOLD JULIA Switzerland AINI RAHMI QUROTA Korea Republic of ARVOLA ORLANDER AULI Sweden AIREY JOHN Sweden ASAHINA SHOTA Japan AIVELO TUOMAS Finland ASAKLE SHADI Israel AKAYGUN SEVIL Turkey ASH DORIS United States AKERSON VALARIE United States ASSAAD YAMMINE Lebanon ÅKESSON NILSSON GUNILLA Sweden ASTON KATHERINE United Kingdom AKINYEMI OLUTOSIN SOLOMON South Africa ASTROM MARIA Sweden AKIRI EFFRAT Israel ATANASOVA SANJA Switzerland AKMAN PERIHAN Germany ATKINS ELLIOTT LESLIE United States AKSOZ BUSRA Turkey ATWATER MARY M United States ALAKOYUN LEMAN Turkey AUCLAIR ALEXANDRA Canada ALARCÓN-OROZCO Mª MARTA Spain AUNING CLAUS Denmark ALINA BEHRENDT Germany AVRAAMIDOU LUCY Netherlands ALLAIRE-DUQUETTE GENEVIEVE Israel AVSAR ERUMIT BANU Turkey ALMEIDA ANTÓNIO Portugal AZAM SAIQA Canada ALMSTRUP CHRISTINE Denmark BABAI REUVEN Israel ALMUKHAMBETOVA AINUR Kazakhstan BACCAGLINI-FRANK ANNA Italy ALONZO ALICIA United States BÄCHTOLD MANUEL France ALSOP STEVE Canada BACKHOUSE ANITA United Kingdom AMARAL EDENIA M. -

Experimental Museology

EXPERIMENTAL MUSEOLOGY Experimental Museology scrutinizes innovative endeavours to transform museum interactions with the world. Analysing cutting-edge cases from around the globe, the volume demonstrates how museums can design, apply and assess new modes of audience engagement and participation. Written by an interdisciplinary group of researchers and research-led professionals, the book argues that museum transformations must be focussed on conceptualising and documenting the everyday challenges and choices facing museums, especially in relation to wider social, political and economic ramifications. In order to illuminate the complexity of these challenges, the volume is structured into three related key dimensions of museum practice – namely institutions, representations and users. Each chapter is based on a curatorial design proposed and performed in collaboration between university-based academics and a museum. Taken together, the chapters provide insights into a diversity of geographical contexts, fields and museums, thus building a comprehensive and reflexive repository of design practices and formative experiments that can help strengthen future museum research and design. Experimental Museology will be of great value to academics and students in the fieldsof museum, gallery and heritage studies, as well as architecture, design, communication and cultural studies. It will also be of interest to museum professionals and anyone else who is interested in learning more about experimentation and design as resources in museums. Marianne Achiam has a PhD in science education, and is an associate professor at the Department of Science Education, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. Michael Haldrup is a professor (wsr) in visual culture and performance design at Roskilde University, Denmark. Kirsten Drotner is a professor of media studies at the University of Southern Denmark and director of two national R&D programmes DREAM and Our Museum. -

Contemporary African

Hassan Hajjaj Morocco’s “Andy Wahloo” What to collect at the fair: Our selection of 15 artists 1-54 London A Limitless Retelling of History Diptyk n°42. février-mars 2018 >> 1 SPECIAL ISSUE: 1-54 LONDON Are you looking to optimise business travel for your company and make it easy for your staff to travel in comfort and peace of mind ? Royal Air Maroc will make your business travel smooth and enjoyable. Connectivity : Modern fleet of 56 aircraft with an average age of 8 years that cover 97 destinations in 4 continents. Network from UK: - a daily direct flight from both Heathrow and Gatwick to Casablanca - 3 weekly direct flights from Manchester to Casablanca - twice weekly direct flights from Heathrow to Rabat Cost Effectiveness: Outstanding fares Bespoke service regardless of the size of the business Frequent Flyer Corporate program Renown Expertise : Awarded the 4-star rating from Skytrax Voted Best Regional Airline to Africa for 3 years running 2015, 2016, 2017. London office : +44 (0)20 7307 5820│Call center : 020 7307 5800│royalairmaroc.com diptyk Rue Mozart, Résidence Yasmine, quartier Racine, Casablanca 20000, Morocco +212 5 22 95 19 08/15 50 [email protected] www.diptykblog.com © Jean-François Robert Director and Editor-in-chief Meryem Sebti editor’s note Artistic Director and Graphic Designer Sophie Goldryng A partner of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair Project Manager and Copy Editor since its first London edition in 2013, Diptyk is now proud Marie Moignard to present its very first issue in English. As an African publication alive to the present day realities of Moroccan Administrative Manager and life, our bimonthly magazine has been documenting the Commercial Back-Office contemporary art scene on the continent since 2009. -

Alphabetical Index

Alphabetical Index H0yer. 0 G, "IS 10< Aaroportos a Navega!fiio Aarea ANA- AUlanz Pace Ass;cura>:ioni e 3 Glacken GmbH 221 EP AiassTcurazioni SpA 337 3C Industriale SpA 335 Aeroquip GmbH '" Allied Corporation International NV • 3M AIS 107 ABrzenef Maschinenlabrik GmbH '"'22 Allied Stevedores (Antwerp) NV • 4P Nicolaus Kempten GmbH "flimel SA 185 Allsecures Assicurazioni SpA 337 A & L Simonazll 335'" AFM 186 Allweilsf AG A Agral; SpA 335 Aga Gas GmbH "1m3 NV '"• A Cilium AIS 107 Agla Gevaer! AIS '"108 Almag SpA 338 A CounlnlOlis SA 313 Agnar, Paul. Fiskeindustrl AIS 108 ALMO Erzeugl1isse Erwio Busch fA. Espersen AIS 107 Agnatl SpA 336 GmbH Alols Zettler Elektrotechnische Fabrik A Gevaerl & Co NV 3 Agnesl SpA 336 '" GmbH A Jespersen & Sen A!S 107 Agrati, A, SpA 336 Alpine AG A lekkas & Bros SA 313 Agricola de Lacticinlos a Cerllral de '" Alpltour Italia SpA 336 A Lommaert NV 3 Peralita Lda '" Alsaclenne d'Alumlnium 185 A Michailides SA 313 Agricultural Bank of Greece '"313 Aisen-Breitenburg Zement- coO A Schulmen Plastics NV-SA 3 Agrippina Lebensversicherung Kalkwarlea GmbH A Silva & Silva Industrlas e Comarcio Aktiengesellschaft Allenberg Metallwerke AG 225 A Stolz Maschinenbau AG '" AGROB Group 01 Companies '" '" Alter SA 508 Aachener Sirassenbahn und Agrob Wessel ServaIs AG '" '" Aluminium Werle Unna AG 225 Enargieversorgungs AG Agro-kemi AIS 108 '" Aluminiumwerk Unna AG Aalborg Stil1slidende AIS 107 Agropecuaria de Navarra, SCoop, '" Aluminium-Werke Wijtoschingen Aannemingsbedrijf Van Lee BV Ltda 508 '" GmbH Aennemingsmaatschappij GElbam -

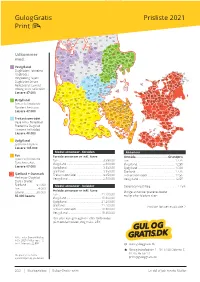

Guloggratis Print Prisliste 2021

9990 Skagen 9982 Ålbæk 9850 9881 Hirtshals Bindslev 9981 Jerup 9970 Strandby 9800 9870 Hjørring Sindal 9900 Frederikshavn 9830 9480 9760 Tårs Løkken Vrå 9750 9300 Øster-Vrå Sæby 9740 9493 9700 Jerslev J 9352 9492 Saltum Brønderslev Dybvad Blokhus 9490 9352 9330 Pandrup Tylstrup 9320 Dronninglund 9440 9381 Hjallerup GulogGratis Aabybro Sulsted 9340 Prisliste 2021 9430 Asaa 9460 Vadum 7730 7741 Brovst 9310 Hanstholm Frøstrup 9690 9400 Vodskov Fjerritslev Nørresundby 9220 9362 9370 9000 Aalborg Ø 7742 Aalborg Gandrup Hals Vesløs 9270 7700 9200 9210 Klarup Print Thisted Aalborg SV Aalborg SØ 9280 9230 Storvorde 9670 Svenstrup 9260 Løgstør 9240 Gistrup 9681 Nibe 9293 Ranum 9530 7752 Støvring Kongerslev Snedsted 7755 7950 9541 Bedsted Thy Erslev 7884 Suldrup 9520 Fur Skørping 9574 9575 Bælum 7770 7900 9600 Terndrup Vestervig Nykøbing 9640 Aars Farsø 7960 7980 9610 9510 Karby Vils Nørager Arden 9560 7970 Hadsund 7760 Redsted 7870 7680 Hurup Thy Roslev Thyborøn 7990 9631 9620 Øster-Assels Gedsted Aalestrup 7790 9500 8970 7673 Thyholm Hobro 9550 Havndal Harboøre 7860 Mariager Spøttrup 9632 8832 Møldrup 8983 7840 Skals Gjerlev J Højslev 8990 Fårup 8981 7800 8831 Spentrup 8950 7620 Skive Ørsted Lemvig Løgstrup 8830 8585 7850 Tjele 8920 8930 8961 Glesborg 7600 7830 Stoholm Randers NV Randers NØ Allingåbro Struer Vinderup 8900 Udkommer 7650 7560 Randers 8586 Ørum Djurs Bøvlingbjerg 7660 8963 8581 8500 Hjerm 8800 8960 Grenaa Bækmarksbro Viborg 8940 Randers SØ Auning Nimtofte Randers SV 8550 8850 8870 Ryomgård 7570 Bjerringbro 8860 Langå 8570 med: 7500 -

Sbi 2020-Vollsmose

Aalborg Universitet Vollsmose Arbejdsrapport – baselineundersøgelse 2019 Bech-Danielsen, Claus; Mechlenborg, Mette; Stender, Marie Publication date: 2020 Document Version Også kaldet Forlagets PDF Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Bech-Danielsen, C., Mechlenborg, M., & Stender, M. (2020). Vollsmose: Arbejdsrapport – baselineundersøgelse 2019. Institut for Byggeri, By og Miljø (BUILD), Aalborg Universitet. SBI Nr. 2020:07 https://sbi.dk/Pages/Vollsmose.aspx General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: October 05, 2021 SBI 2020:07 VOLLSMOSE Arbejdsrapport – baselineundersøgelse 2019 Vollsmose Arbejdsrapport – baselineundersøgelse 2019 Claus Bech-Danielsen Mette Mechlenborg Marie Stender SBi 2020:07 BUILD, Aalborg Universitet København ꞏ 2020 Titel Vollsmose Undertitel Arbejdsrapport - baselineundersøgelse 2019 Serietitel SBi 2020:07 Udgave 1. udgave Udgivelsesår 2020 Forfattere Claus Bech-Danielsen, Mette Mechlenborg, Marie Stender Sprog Dansk Sidetal 69 Litteratur- henvisninger Side 68 Emneord Bolig, boligområder, bypolitik, byudvikling ISBN 978-87-563-1944-7 Fotos Claus Bech-Danielsen Omslag Claus Bech-Danielsen Udgiver BUILD, Aalborg Universitet, A.C. -

Supersygehus for Hele Regionen Fælles Akutmodtagelse Vil Redde Flere Liv Patienter Behandles Via Internettet 08 Ouhfør,Nu Og I Fremtiden

14. - 15. APRIL 2012 JydskeVestkysten Vejle Amts Folkeblad Fredericia Dagblad Fyns Amts Avis OUH Fyens Stiftstidende 100 Supersygehus for hele regionen Fælles Akutmodtagelse vil redde flere liv Patienter behandles via internettet 08 OUHfør,nu og i fremtiden 1912 kunne Odense tilbyde det nyeste og mest moderne sygehus i provinsen. Bygget og indrettet med det kun to år ældre Rigshospitalet som forbillede. II 2021 kan Odense tilbyde det nyeste og mest mo- derne supersygehus i Danmark. Bygget og indrettet med ny teknologi, som på nuværende tidspunkt be- finder sig på et forsøgsstadium. Men indtil da er der god grund til at markere den indsats og udvikling, som Odense Universitetsho- spital har leveret i 100 år. Med en kapacitet og lægefaglige specialer, der rækker ud over de regionale grænser. Indhold Forgodtnokvar det et sygehus for Odense By og Amt, der blev taget i brug for 100 år siden. Og byg- ningerne står der endnu, selv om de er klemt inde af Artikler flere årtiers nybyggeri. For trods Men det er som universitets- Syge børn har brug for trygge rammer 4-5 hospital og flagskib i Region avanceret Syddanmarks sundhedsvæsen, Helt styr på hjertet 8-10 teknologi at OUH har en førende posi- tion og fremtid i det danske Ny akutmodtagelse vil redde flere liv 12-14 handler sundhedsvæsen. hverdagen på Minutterne tæller på det nye traumecenter 16-18 Et 100-års jubilæum i en stor Uden mad og drikke duer patienten ikke 20-22 et stort hospital virksomhed er en naturlig an- også om alle de ledning til både at kigge tilbage Et stort skridt ind i fremtiden 26-27 og frem i tiden. -

Report: Making Your Business More Gender Inclusive: an Opportunity for Growth

Report REPORT: MAKING YOUR BUSINESS MORE GENDER INCLUSIVE: AN OPPORTUNITY FOR GROWTH Work package 6 number: Task number: 6.4 Contributors: Carmen Fenollosa and Suzana Filipecki Martins Institutions: Ecsite Revision Date: 25 July 2016 Status: Final This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (H2020-GERI-2014-1) under the grant agreement No. 665566. 1 Report Summary: 2 Summary of Sessions 3 Welcome and introduction by Marjolein van Breemen 3 Key note by Julie Ward 3 Key note by Donna Herdsman 3 Presentation by Marianne Achiam 4 Conversation with David McDonald and Ken Armistead 4 Sharing Experiences 5 What is next? 9 A few tweets from the event 9 Pictures 11 Speakers’ Bios: 15 Marianne Achiam, University of Copenhagen, Denmark 15 Ken Armistead, PPG Industries, UK. 15 Marjolein van Breemen, NEMO Science Museum, the Netherlands 15 Quentin Cooper, Science Oxford, UK 15 Donna Herdsman, Hewlett Packard, UK 15 David Macdonald, L’Oréal Foundation, France 15 Julie Ward, Member of the European Parliament, UK 16 Feedback from participants 16 Participants’ list 16 Summary: This report presents the outcomes of the workshop “Making your Business More Gender Inclusive: An Opportunity for Growth”, which took place on 30 June 2016 in Brussels. Organised by Ecsite, in the context of the Hypatia project, “Making your Business More Gender Inclusive” gathered 64 top European industry representatives, European policy makers, researchers and museum professionals from 14 countries to discuss the role the industry sector has in engaging young people, and especially girls, in STEM related careers. -

America Letter Sept 2005 Vol

America Letter Sept 2005 Vol. XIX, No. 3 Your Museum in the An International THE DANISH IMMIGRANT MUSEUM Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, Protector Heart of the Continent Cultural Center BOX 470 • ELK HORN, IOWA 51531 ® Member of the American Association of Museums Hans Christian Andersen Parade’s U.S. Tour As part of the world-wide celebration of the bicenten- “We are absolutely delighted and pleased to assist nial of Hans Christian Andersen’s birth, the Museum is in bringing the Hans Christian Andersen Parade to the pleased to sponsor the U.S. tour of the well-known and U.S., and we are especially grateful to Dennis for his popular Hans Christian Andersen Parade from Odense, wonderful support assisting us in bringing the Parade Denmark. This is the company’s fi rst U.S. tour, which to this country,” said Dr. John Mark Nielsen, Execu- will take place from October 7-18, 2005 and include tive Director. “We saw a performance this summer performances from Boston and New York to Omaha, in Odense, and those who can see it here are in for a Des Moines, and Chicago. treat.” The cast of 25 actors, ranging in age from 10 to 19, Members of the Odense City Council and Cultural present scenes from such well-known tales as “The Ugly Department will be accompanying the Hans Christian Duckling,” “The Little Match Girl,” The Emperor’s New Andersen Parade, along with a journalist from the Clothes.” Led by actor/director Torben Iversen, the Parade newspaper, Fyens Stiftstidende. The Museum’s Director has performed for more than 15 years and given several of Development, Thomas Hansen, himself a native of thousand performances.