A Comparative Study of the Impact of Principals' Leadership Styles on the Job Satisfaction of Teachers Asif Iqbal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Supply & Sanitation

WATER SUPPLY & SANITATION 149 WATER SUPPLY & SANITATION VISION To improve quality of life of the people of Punjab through provision of safe drinking water and sanitation coverage to the entire community. POLICY This important social sector assumes the policy of provision of safe and potable drinking water, sanitation and coverage of the entire community particularly in barani and brackish areas. Emphasis has been laid on encouraging Participatory Management - Community mobilization in project. Coverage will be provided to the rural areas through encouragement of integrated rural water supply and sanitation schemes. Waste water treatment plants will be provided for improving environmental pollution and protecting Water Bodies. STRATEGIC INITIATIVES / NEW INTERVENTIONS ¾ 993 water supply and sanitation schemes have been conceived for the year 2008-09 with a total financial outlay of Rs.8000 million. Execution of these interventions will result into substantial improvement in the population coverage. ¾ A special package has been reflected in the MTDF 2008-09 under “Community based Sanitation Program”. By implementation of this project there will be visible improvement in the sanitation, particularly in Rural Areas and Small Towns. ¾ MTDF 2008-09 provides “Block Allocation” for various components of the Sector. The schemes against these blocks will be identified through participation of the local communities. ¾ In order to ensure equitable distribution of supplies and for water conservation, water metering concept is being introduced in the rural areas. This intervention will control wastage of water and will lead to the sustainability of the schemes. ¾ Presently there is a huge disparity amongst districts regarding the resource provisions. This imbalance is being minimized by providing more funds to the deprived/low profile districts as defined in MICS. -

Mtdf 2007-2010 Development Programme 2 0

GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB MTDF 2007-2010 DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 MTDF 2007-10 ABSTRACT (Rs. In million) Sr. Allocation % of Core Projections % of Core Projections 2009- % of Core Sector No. 2007-08 2007-08 2008-09 2008-09 10 2009-10 A Social Sectors 44377.450 47.7 57505.000 49.1 71655.000 50.5 1 Education 21480.450 23.1 29050.000 24.8 36500.000 25.7 (i) School Education 8488.000 9.1 10950.000 9.4 14000.000 9.9 (ii) Higher Education 9936.000 10.7 12600.000 10.8 15500.000 10.9 (iii) Special Education 954.450 1.0 2000.000 1.7 2500.000 1.8 (iv) Literacy 1200.000 1.3 2000.000 1.7 2500.000 1.8 (v) Sports 902.000 1.0 1500.000 1.3 2000.000 1.4 2 Health 6500.000 7.0 10000.000 8.5 12800.000 9.0 3 Water Supply & Sanitation 6500.000 7.0 8700.000 7.4 10600.000 7.5 4 Social Protection 616.000 0.7 900.000 0.8 1300.000 0.9 5 Regional Planning 2326.000 2.5 3500.000 3.0 4400.000 3.1 6 Local Government & Community Development 6955.000 7.5 5355.000 4.6 6055.000 4.3 (i) LG&CD 2100.000 2.3 3500.000 3.0 4200.000 3.0 (ii) Tameer-e-Punjab Programme 1855.000 2.0 1855.000 1.6 1855.000 1.3 (iii) Local Development Programme 2000.000 2.2 0.000 0.0 0.000 0.0 (iv) Community Uplift Programme 1000.000 1.1 0.000 0.0 0.000 0.0 B Infrastructure Development 32354.000 34.8 40500.000 34.6 45500.000 32.0 7 Roads 14300.000 15.4 16000.000 13.7 17000.000 12.0 8 Irrigation 11000.000 11.8 13000.000 11.1 16000.000 11.3 9 Public Buildings (Housing) 800.000 0.9 1500.000 1.3 1500.000 1.1 10 Public Buildings (Offices) 2450.000 2.6 4000.000 3.4 5000.000 3.5 11 Urban Development 3804.000 4.1 6000.000 5.1 6000.000 4.2 C Production Sectors 7053.000 7.6 10210.000 8.7 13230.000 9.3 12 Agriculture 2800.000 3.0 3800.000 3.2 5000.000 3.5 13 Forestry, Wildlife & Fisheries 690.000 0.7 1060.000 0.9 1350.000 1.0 (i) Forestry 220.000 0.2 310.000 0.3 450.000 0.3 (ii) Wildlife 350.000 0.4 550.000 0.5 650.000 0.5 MTDF 2007-10 ABSTRACT (Rs. -

District CHAKWAL CRITERIA for RESULT of GRADE 8

District CHAKWAL CRITERIA FOR RESULT OF GRADE 8 Criteria CHAKWAL Punjab Status Minimum 33% marks in all subjects 92.71% 87.61% PASS Pass + Pass Pass + Minimum 33% marks in four subjects and 28 to 32 94.06% 89.28% with Grace marks in one subject Marks Pass + Pass with Grace Pass + Pass with grace marks + Minimum 33% marks in four 99.08% 96.89% Marks + subjects and 10 to 27 marks in one subject Promoted to Next Class Candidate scoring minimum 33% marks in all subjects will be considered "Pass" One star (*) on total marks indicates that the candidate has passed with grace marks. Two stars (**) on total marks indicate that the candidate is promoted to next class. PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, RESULT INFORMATION GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Pass + Students Students Students Pass % with Pass + Gender Promoted Registered Appeared Pass 33% marks Promoted % Students Male 7754 7698 7058 91.69 7615 98.92 Public School Female 8032 7982 7533 94.37 7941 99.49 Male 1836 1810 1652 91.27 1794 99.12 Private School Female 1568 1559 1484 95.19 1555 99.74 Male 496 471 390 82.80 444 94.27 Private Candidate Female 250 243 205 84.36 232 95.47 19936 19763 18322 PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Overall Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 65-232-295 Muhammad Abdul Rehman 479 1st 65-141-174 Maryam Batool 476 2nd 65-141-208 Wajeeha Gul 476 2nd 65-208-182 Sawaira Azher 474 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Male Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 65-232-295 Muhammad Abdul Rehman 479 1st 65-231-135 Muhammad Huzaifa 468 2nd 65-183-183 Fasih Ur Rehman 463 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 8 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL FEMALE Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 65-141-174 Maryam Batool 476 1st 65-141-208 Wajeeha Gul 476 1st 65-208-182 Sawaira Azher 474 2nd 65-236-232 Kiran Shaheen 473 3rd j b i i i i Punjab Examination Commission Grade 8 Examination 2019 School wise Results Summary Sr. -

0 95 0 89 93.68 6 1 3 16 49 21 Science 53 0 53 0 52 98.11 1 0 15 4 27 6 Total 149 0 148 0 141 95.27 7 1 18 4 43 55 21 101006 Govt

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION, RAWALPINDI BISER COMPUTER SECTION INSTITUTION-WISE TOTAL CANDIDATES APPEARED / PASSED / PASS PERCENTAGE DATE: JULY 15, 2019 Page 1 of 148 GROUPS ENRO CANC APPE UFM/ PASS PASS FAI ABS --PASSING GRADE WISE-- LLED LLED ARED ETC ED %AGE LED ENT A A+ B C D E CODE INSTITUTE NAME 101001 GOVT. GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL NO. 1 ATTOCK GENERAL 151 0 151 0 91 60.26 60 0 7 23 34 27 SCIENCE 254 0 252 0 215 85.32 37 2 43 18 51 81 22 TOTAL 405 0 403 0 306 75.93 97 2 50 18 74 115 49 101002 GOVT. GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL NO. 2 ATTOCK GENERAL 61 0 60 0 37 61.67 23 1 5 1 9 10 12 SCIENCE 175 0 175 0 135 77.14 40 0 21 14 44 45 11 TOTAL 236 0 235 0 172 73.19 63 1 26 15 53 55 23 101003 GOVT. GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL BOLIANWAL (ATTOCK) GENERAL 31 0 30 0 20 66.67 10 1 2 7 8 3 SCIENCE 43 0 43 0 38 88.37 5 0 11 4 17 6 TOTAL 74 0 73 0 58 79.45 15 1 13 4 24 14 3 101004 GOVT. GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL GHOURGHUSHTI, GENERAL 79 0 79 0 62 78.48 17 0 12 2 25 20 3 (ATTOCK) SCIENCE 20 0 20 0 20 100 0 0 5 4 9 2 TOTAL 99 0 99 0 82 82.83 17 0 17 6 34 22 3 101005 GOVT. -

Short Notice Inviting Tenders

E/ Newfolder1/ SHORT NOTICE INVITING TENDER2012.doc SHORT NOTICE INVITING TENDERS Sealed tenders based on item rates/ percentage above or below on market rate system amended for District Chakwal up to the date of receipt of tenders are hereby invited in accordance with Punjab Procurement Rules, 2014 (amended) for the works mentioned below, from contractors/firms enlisted with C&W Department and Works & Services Department District Government Chakwal for the year 2014-15 in the field of Buildings works. Tender documents can be obtained from the office of the undersigned, Executive District Officer, Works and Services Chakwal/Executive District Officer, Education against written request accompanied with attested copies of Enlistment/renewal letters and fee receipt, Valid PEC license, authority, on Pad Form of contractor/firm, identity Card of contractor/Managing Partner of the Firm along with registered power of attorney, on payment of prescribed Tender Fee. Tendered rates and amounts should be filled in figure as well as in words. Tenders should be signed as per general directions given in the tender documents. No rebate on tendered Rates will be acceptable. Tenders will be received in the office of the Executive District Officer, Education, Chakwal up to 2.00 P.M hours on the date of opening of tenders and will be opened immediately thereafter by the District tender board, Chakwal constituted by the Government of Punjab Local Government and Community Development Lahore No. S.O.D.G (Dev) (LG) 9-7/2009 dated. 23-12-2010 in the presence of intending contractors or their representatives as per following schedule:- Date of receipt of applications. -

Short Notice Inviting Tenders

SHORT NOTICE INVITING TENDERS Sealed tenders T.S based on item rates/percentage are hereby invited for the works mentioned below from the contractors/firms enlisted with C&W department punjab / Chief Engineer District Supports and Monitoring Department Lahore/ E.D.O. (W&S) Chakwal in the field of Building Sector for the year 2016-17. Tender documents on payment of prescribed tender fee in shape of CDR can be obtained soon after publication of advertisement in daily newspapers during working hours upto 22.12.2016 from the office of the undersigned or E.D.O (W&S) Chakwal on written request accompanied with attested copies of Enlistment/renewal letters and fee receipt for 2016-17 and Valid/Fresh PEC license for 2016. The representatives of the contractors / firms should bring authority letter and application on pad form of the original contractor. In case of managing partner of the firm, power of attorney and partnership deed will be required. Tenders will be received in the office of the undersigned upto 2.00 P.M on 24.12.2016 and will be opened at 2:30 PM on same day by the District Tender Board, Chakwal in the presence of participanting contractors or their representatives. Conditional tenders and tenders not accompanied with earnest money @ 2% of the bid / tendered amount in shape of deposit at call issued by any scheduled bank will not be entertained /accepted. Tendered rates and amounts should be filled in figure as well as in words and Tenders should be signed as per general directions given in the tender documents. -

Detail of Posts Notified in Bs – 17 (Female)

- 164 - ANNEXURE – “D” NAME OF POSTS IN BS – 17 (FEMALE) DETAIL OF POSTS NOTIFIED IN BS – 17 (FEMALE) Sr. Name of Posts No. of Posts Remarks No. Assistant Directors, in the offices of Director Public Instruction (S.E/E.E), and In the offices where posts 1. in the offices of Executive District Officer 18 (Education), in the Punjab. (From exists. Teaching Staff) 1. 25 posts of Dy. HMs BS-17 shifted by the District Govt. in newly upgraded High Schools. 2. 20 posts of Dy. H.Ms (BS- 17) upgraded to BS-18 and shifted to those Tehsils Deputy Headmistress, in Girls High where posts of Deputy 2. 78-45= 33 District Education Officer Schools. (W-EE), not sanctioned / required. 3. Remaining 33 posts of Dy. HMs (BS-17), shifted to those High Schools of BS-20 having High Enrolment. Detail of these Institutions are shown at Annexture –D (A). As per sanction strength subject to the condition that repetition of subjects Subject Specialists, of Government shall not be allowed in any 3. Colleges for Elementary Teachers Training 56+40=96 case (40-posts of SS BS-17 (Female). of 4-GCETs (W) merged in GCETs (M) As per sanction strength Subject Specialist, Government subject to the condition 4. 10 that repetition of subjects Comprehensive Girls High Schools. shall not be allowed in any case As per sanction strength Subject Specialist, of Government subject to the condition 5. Comprehensive Girls Higher Secondary that repetition of subjects Schools. 10 shall not be allowed in any case As per sanction strength Subject Specialist, of Government Girls subject to the condition that 6. -

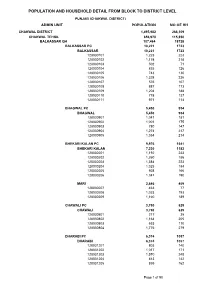

Chakwal Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (CHAKWAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH CHAKWAL DISTRICT 1,495,982 266,109 CHAKWAL TEHSIL 656,978 115,850 BALKASSAR QH 107,464 18728 BALKASSAR PC 10,221 1723 BALKASSAR 10,221 1723 128030101 1,223 223 128030102 1,174 218 128030103 502 71 128030104 835 126 128030105 743 130 128030106 1,328 236 128030107 576 107 128030108 887 173 128030109 1,204 188 128030110 778 137 128030111 971 114 BHAGWAL PC 5,450 934 BHAGWAL 5,450 934 128030901 1,041 181 128030902 1,001 175 128030903 780 147 128030904 1,274 217 128030905 1,354 214 BHEKARI KALAN PC 9,976 1641 BHEKARI KALAN 7,330 1182 128030201 1,192 233 128030202 1,260 186 128030203 1,584 223 128030204 1,025 184 128030205 928 166 128030206 1,341 190 MARI 2,646 459 128030207 463 77 128030208 1,023 193 128030209 1,160 189 CHAWALI PC 3,790 629 CHAWALI 3,790 629 128030801 217 35 128030802 1,164 205 128030803 633 110 128030804 1,776 279 DHARABI PC 6,374 1057 DHARABI 6,374 1057 128031201 803 140 128031202 1,017 171 128031203 1,570 248 128031204 813 142 128031205 859 162 Page 1 of 50 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (CHAKWAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 128031206 1,312 194 HASAL PC 4,740 804 HASAL 4,740 804 128031301 451 96 128031302 611 114 128031303 1,111 183 128031304 970 145 128031305 861 145 128031306 736 121 RAKH HASAL 0 0 128031307 0 0 KALLU JO PC 9,653 1853 HASTAL 1,829 360 128030303 684 133 128030304 1,145 227 KALLU JO 2,275 381 128030301 929 109 128030302 1,346 272 RAKH CHHANB -

Pak Pos and RMS Offices 3Rd Ed 1962

Instructions for Sorting Clerks and Sorters ARTICLES ADDRl!SSBD TO TWO PosT-TOWNS.-If the address Dead Letter Offices receiving articles of the description re 01(an article contains the names of two post-town, the article ferred in this clause shall be guided by these instructions so far should, as a general rule, be forwarded to whichever of the two as the circumstances of each case admit of their application. towns is named last unless the last post-town- Officers employed in Dead Letter Offices are selected for their special fitness for the work and are expected to exercise intelli ( a) is obviously meant to indicate the district, in which gence and discretion in the disposal of articles received by case the article should be . forwar ~ ed ~ · :, the first them. named post-town, e. g.- A. K. Malik, Nowshera, Pes!iaivar. 3. ARTICLES ADDRESSED TO A TERRITORIAL DIVISION WITH (b) is intended merely as a guide to the locality, in which OUT THE ADDITION OF A PosT-TOWN.-If an article is addressed case the article should be forwarded to the first to one of the provinces, districts, or other territorial divisions named post-town, e. g.- mentioned in Appendix I and the address does not contain the name of any post-town, it should be forwarded to the post-town A. U. Khan, Khanpur, Bahawalpur. mentioned opposite, with the exception of articles addressed to (c) Case in which the first-named post-town forms a a military command which are to be sent to its headquarters. component part of the addressee's designation come under the general rule, e. -

District CHAKWAL CRITERIA for RESULT of GRADE 5

District CHAKWAL CRITERIA FOR RESULT OF GRADE 5 Criteria CHAKWAL Punjab Status Minimum 33% marks in all subjects 93.12% 88.32% PASS Pass + Pass Pass + Minimum 33% marks in four subjects and 28 to 32 94.13% 89.91% with Grace marks in one subject Marks Pass + Pass with Grace Pass + Pass with grace marks + Minimum 33% marks in four 98.33% 96.72% Marks + subjects and 10 to 27 marks in one subject Promoted to Next Class Candidate scoring minimum 33% marks in all subjects will be considered "Pass" One star (*) on total marks indicates that the candidate has passed with grace marks. Two stars (**) on total marks indicate that the candidate is promoted to next class. PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, RESULT INFORMATION GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Pass + Students Students Students Pass % with Pass + Gender Promoted Registered Appeared Pass 33% marks Promoted % Students Male 7888 7817 7019 89.79 7592 97.12 Public School Female 8404 8339 7888 94.59 8252 98.96 Male 3007 2986 2837 95.01 2958 99.06 Private School Female 2436 2426 2360 97.28 2411 99.38 Male 189 170 143 84.12 164 96.47 Private Candidate Female 98 91 81 89.01 88 96.70 22022 21829 20328 PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Overall Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 15-235-135 Khadija Ramzan 481 1st 15-183-142 Ahtasham Ali 478 2nd 15-183-271 Ali Meesum 478 2nd 15-192-263 Izan Fatima 478 2nd 15-186-110 Haider Abbas 476 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL Male Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 15-183-142 Ahtasham Ali 478 1st 15-183-271 Ali Meesum 478 1st 15-186-110 Haider Abbas 476 2nd 15-183-233 Saad Ulah 472 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: CHAKWAL FEMALE Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 15-235-135 Khadija Ramzan 481 1st 15-192-263 Izan Fatima 478 2nd 15-192-167 Unaiza Bibi 470 3rd j b i i i i Punjab Examination Commission Grade 5 Examination 2019 School wise Results Summary Sr. -

Chakwal Provincial Assembly General Elections Polling Scheme 2018

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN FORM-28 [see rule 50] LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY OF Election to the National Assembly of the PP-21 CHAKWAL-I S. No. of Number of voters assigned to polling In Case of Rural Areas In Case of Urban Areas voters on the Number of polling booths station Sr. No. No. and Name of Polling Station electoral roll Name of Electoral Census Block Name of Electoral Census Block in case electoral area Male Female Total Male Female Total Areas Code Areas Code is bifurcated 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 THANIL KAMAL 128050301 - - 553 0 553 Government Boys High School 1 THANIL KAMAL 128050302 - - 274 0 274 2 0 2 Thanil Kamal THANIL KAMAL 128050303 - - 173 0 173 1 Total - - - 1000 0 1000 2 0 2 THANIL KAMAL 128050301 - - 0 519 519 Government Boys High School 2 THANIL KAMAL 128050302 - - 0 285 285 0 2 2 Thanil Kamal THANIL KAMAL 128050303 - - 0 137 137 2 Total - - - 0 941 941 0 2 2 THANIL KAMAL 128050304 - - 0 194 194 THANIL KAMAL 128050305 - - 0 234 234 Government Girls High School 3 THANIL KAMAL 128050306 - - 0 152 152 0 2 2 Thanil Kamal THANIL KAMAL 128050307 - - 0 271 271 (DANGI ZAIR) 3 Total - - - 0 851 851 0 2 2 THANIL KAMAL 128050304 - - 199 0 199 THANIL KAMAL 128050305 - - 300 0 300 Government Girls High School 4 THANIL KAMAL 128050306 - - 164 0 164 2 0 2 Thanil Kamal THANIL KAMAL 128050307 - - 302 0 302 (DANGI ZAIR) 4 Total - - - 965 0 965 2 0 2 Government Boys Primary 5 HARAJ (PIND DAKHLI) 128050205 - - 512 477 989 1 1 2 School Harraj 5 Total - - - 512 477 989 1 1 2 Government Boys Elementary 6 HARAJ -

Table -24 Selected Housing Characteristics of Rural Localities Name of Mauza / Deh / Village / Settlment Hadbast Number / Deh N

TABLE -24 SELECTED HOUSING CHARACTERISTICS OF RURAL LOCALITIES HOUSING CHARACTERISTICS HADBAST NAME OF MAUZA / HOUSING FACILITIES AVERAGE NUMBER / TYPE OF HOUSING UNIT DEH / VILLAGE / HOUSEHOLD DEH SETTLMENT SIZE NUMBER POTABLE WATER ELECTRICITY GAS KITCHEN BATH ROOM LATRINE TOTAL PACCA SEMI PACCA KACHA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 CHAKWAL DISTRICT 216728 175546 28811 12371 168884 200903 38652 191426 191394 178445 5.51 CHAKWAL TEHSIL 92224 74617 14281 3326 72930 89578 18535 84433 82126 78788 5.54 BALKASSAR QH 18777 14950 2797 1030 15216 17772 2220 16836 16707 16089 5.60 BALKASSAR PC 1692 1493 143 56 1496 1674 279 1625 1648 1635 5.59 BALKASSAR 0000067 1692 1493 143 56 1496 1674 279 1625 1648 1635 5.59 BHAGWAL PC 930 841 48 41 863 872 2 858 861 850 5.80 BHAGWAL 0000032 930 841 48 41 863 872 2 858 861 850 5.80 BHEKARI KALAN PC 1645 1158 412 75 1532 1624 16 1560 1578 1560 5.99 BHEKARI KALAN 0000069 1182 844 304 34 1165 1174 10 1137 1149 1143 6.08 MARI 0000071 463 314 108 41 367 450 6 423 429 417 5.76 CHAWALI PC 628 444 128 56 576 604 6 574 593 590 6.00 CHAWALI 0000037 628 444 128 56 576 604 6 574 593 590 6.00 DHARABI PC 1057 910 83 64 630 904 29 900 920 838 6.03 DHARABI 0000044 1057 910 83 64 630 904 29 900 920 838 6.03 HASAL PC 805 489 238 78 741 771 59 695 704 546 5.89 HASAL 0000002 805 489 238 78 741 771 59 695 704 546 5.89 RAKH HASAL 0000001 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 KALLU JO PC 1854 1567 218 69 1283 1805 387 1751 1755 1717 4.96 HASTAL 0000072 359 307 45 7 277 356 1 343 332 308 4.98 KALLU JO 0000075 385 286 91 8 276 379 287 355 363 360