Classification of Lithic Artefacts from the British Late Glacial and Holocene Periods Is Offered in This Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nile Valley-Levant Interactions: an Eclectic Review

Nile Valley-Levant interactions: an eclectic review The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bar-Yosef, Ofer. 2013. Nile Valley-Levant interactions: an eclectic review. In Neolithisation of Northeastern Africa, ed. Noriyuki Shirai. Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence, and Environment 16: 237-247. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:31887680 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP In: N. Shirai (ed.) Neolithization of Northeastern Africa. Studies in Early Near Eastern: Production, Subsistence, & Environment 16, ex oriente: Berlin. pp. 237-247. Nile Valley-Levant interactions: an eclectic review Ofer Bar-Yosef Department of Anthropology, Harvard University Opening remarks Writing a review of a prehistoric province as an outsider is not a simple task. The archaeological process, as we know today, is an integration of data sets – the information from the field and the laboratory analyses, and the interpretation that depends on the paradigm held by the writer affected by his or her personal experience. Even monitoring the contents of most of the published and online literature is a daunting task. It is particularly true for looking at the Egyptian Neolithic during the transition from foraging to farming and herding, when most of the difficulties originate from the poorly known bridging regions. A special hurdle is the terminological conundrum of the Neolithic, as Andrew Smith and Alison Smith discusses in this volume, and in particular the term “Neolithisation” that finally made its way to the Levantine literature. -

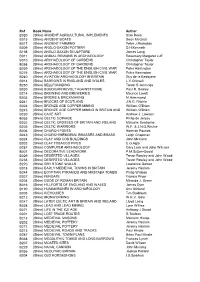

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

A CRITICAL EVALUATION of the LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD of the CHALK UPLANDS of NORTHWEST EUROPE Lesley

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CHALK UPLANDS OF NORTHWEST EUROPE The Chilterns, Pegsdon, Bedfordshire (photograph L. Blundell) Lesley Blundell UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD September 2019 2 I, Lesley Blundell, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 3 4 Abstract Our understanding of early human behaviour has always been and continues to be predicated on an archaeological record unevenly distributed in space and time. More than 80% of British Lower-Middle Palaeolithic findspots were discovered during the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the majority from lowland fluvial contexts. Within the British planning process and some academic research, the resultant findspot distributions are taken at face value, with insufficient consideration of possible bias resulting from variables operating on their creation. This leads to areas of landscape outside the river valleys being considered to have only limited archaeological potential. This thesis was conceived as an attempt to analyse the findspot data of the Lower-Middle Palaeolithic record of the Chalk uplands of southeast Britain and northern France within a framework complex enough to allow bias in the formation of findspot distribution patterns and artefact preservation/discovery opportunities to be identified and scrutinised more closely. Taking a dynamic, landscape = record approach, this research explores the potential influence of geomorphology, 19th/early 20th century industrialisation and antiquarian collecting on the creation of the Lower- Middle Palaeolithic record through the opportunities created for artefact preservation and release. -

Non-Biface Assemblages in Middle Pleistocene Western Europe. A

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ART and SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Non-Biface Assemblages in Middle Pleistocene Western Europe. A comparative study. by Hannah Louise Fluck Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2011 1 2 Abstract This thesis presents the results of an investigation into the Clactonian assemblages of Middle Pleistocene souther Britain. By exploring other non-biface assemblages (NBAs) reported from elsewhere in Europe it seeks to illuminate our understanding of the British assemblages by viewing them in a wider context. It sets out how the historical and geopolitical context of Palaeolithic research has influenced what is investigated and how, as well as interpretations of assemblages without handaxes. A comparative study of the assemblages themselves based upon primary data gathered specifically for that purpose concludes that while there are a number of non-biface assemblages elsewhere in Europe the Clactonian assemblages do appear to be a phenomenon unique to the Thames Valley in early MIS 11. -

Quartz Technology in Scottish Prehistory

Quartz technology in Scottish prehistory by Torben Bjarke Ballin Scottish Archaeological Internet Report 26, 2008 www.sair.org.uk Published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, www.socantscot.org.uk with Historic Scotland, www.historic-scotland.gov.uk and the Council for British Archaeology, www.britarch.ac.uk Editor Debra Barrie Produced by Archétype Informatique SARL, www.archetype-it.com ISBN: 9780903903943 ISSN: 1473-3803 Requests for permission to reproduce material from a SAIR report should be sent to the Director of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports series rests with the SAIR Consortium and the individual authors. The maps are reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of The Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ©Crown copyright 2001. Any unauthorized reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Historic Scotland Licence No GD 03032G, 2002. The consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, advertising or promotional purposes, the creation of new collective works or resale. ii Contents List of illustrations. vi List of tables . viii 1 Summary. 1 2 Introduction. 2 2.1 Project background, aims and working hypotheses . .2 2.2 Methodology . 2 2.2.1 Raw materials . .2 2.2.2 Typology. .3 2.2.3 Technology . .3 2.2.4 Distribution analysis. 3 2.2.5 Dating. 3 2.3 Project history . .3 2.3.1 Pilot project. 4 2.3.2 Main project . -

MOST ANCIENT EGYPT Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu MOST ANCIENT EGYPT oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber MOST ANCIE NT EGYPT William C. Hayes EDITED BY KEITH C. SEELE THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO & LONDON oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-17294 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada © 1964, 1965 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1965. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu WILLIAM CHRISTOPHER HAYES 1903-1963 oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu INTRODUCTION WILLIAM CHRISTOPHER HAYES was on the day of his premature death on July 10, 1963 the unrivaled chief of American Egyptologists. Though only sixty years of age, he had published eight books and two book-length articles, four chapters of the new revised edition of the Cambridge Ancient History, thirty-six other articles, and numerous book reviews. He had also served for nine years in Egypt on expeditions of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the institution to which he devoted his entire career, and more than four years in the United States Navy in World War II, during which he was wounded in action-both periods when scientific writing fell into the background of his activity. He was presented by the President of the United States with the bronze star medal and cited "for meritorious achievement as Commanding Officer of the U.S.S. VIGILANCE ... in the efficient and expeditious sweeping of several hostile mine fields.., and contributing materially to the successful clearing of approaches to Okinawa for our in- vasion forces." Hayes' original intention was to work in the field of medieval arche- ology. -

ADALYA the Annual of the Koç University Suna & İnan Kıraç Research Center for Mediterranean Civilizations

21 2018 ISSN 1301-2746 ADALYA The Annual of the Koç University Suna & İnan Kıraç Research Center for Mediterranean Civilizations (OFFPRINT) AThe AnnualD of theA Koç UniversityLY Suna A& İnan Kıraç Research Center for Mediterranean Civilizations (AKMED) Adalya, a peer reviewed publication, is indexed in the A&HCI (Arts & Humanities Citation Index) and CC/A&H (Current Contents / Arts & Humanities) Adalya is indexed in the Social Sciences and Humanities Database of TÜBİTAK/ULAKBİM TR index. Mode of publication Worldwide periodical Publisher certificate number 18318 ISSN 1301-2746 Publisher management Koç University Rumelifeneri Yolu, 34450 Sarıyer / İstanbul Publisher Umran Savaş İnan, President, on behalf of Koç University Editor-in-chief Oğuz Tekin Editor Tarkan Kahya Advisory Board (Members serve for a period of five years) Prof. Dr. Engin Akyürek, Koç University (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Mustafa Adak, Akdeniz University (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Nicholas D. Cahill, University of Wisconsin-Madison (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Thomas Corsten, Universität Wien (2014-2018) Prof. Dr. Edhem Eldem, Boğaziçi University / Collège de France (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Mehmet Özdoğan, Emeritus, Istanbul University (2016-2020) Prof. Dr. C. Brian Rose, University of Pennsylvania (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Christof Schuler, DAI München (2017-2021) Prof. Dr. R. R. R. Smith, University of Oxford (2016-2020) English copyediting Mark Wilson © Koç University AKMED, 2018 Production Zero Production Ltd. Abdullah Sok. No. 17 Taksim 34433 İstanbul Tel: +90 (212) 244 75 21 • Fax: +90 (212) 244 32 09 [email protected]; www.zerobooksonline.com Printing Oksijen Basım ve Matbaacılık San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. 100. Yıl Mah. Matbaacılar Sit. 2. -

A New Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Facies at Belba~I Rock Shelter on the Mediterranean Coast of Anatolia

A NEW UPPER PALAEOLITHIC AND MESOLITHIC FACIES AT BELBA~I ROCK SHELTER ON THE MEDITERRANEAN COAST OF ANATOLIA This article is dedicated to the memmy of the late Ordinarius Professor Dr. Muzaffer ~enyürek, Chairman of the Division of Palaeoanthropology, Univer- sity of Ankara. Doç. Dr. ENVER Y. BOSTANCI The rock shelter at Belba~~~ is situated about five kms. from the Beldibi rock shelter and is on the western side of the bay of Antalya. It is approximately 300 metres above sea level and is at the head of a shallow valley which runs down to the sea and is covered with pine trees. The new coastal road which has recently been completed passes near the Belba~~~ rock shelter but it can only be reached on foot and is an hour's climb from the road. I discovered this rock shelter during the season of 1959 but the first opportunity I had to make a sounding was in September 1960 °. The journey from Antalya can also be made by motor-boat and this takes about three hours. Belba~~~ is a narrow pass through which ran an old Roman road leading to the interior of Lycia. At the top is a small plateau which has been cleared of trees and cultivated by the present-day villagers. On the north-eastern side of this plateau the mountain rises up steeply again and a rock shelter has been formed in the cretaceous limestone The Beldibi and Belba~~~ excavations continued in May and September 1960. I must thank the Professors Council of the Faculty of Letters for their help in the carrying out of these excavations and my Professor and Dean of the Faculty, Ord. -

JOHN WYMER Copyright © British Academy 2007 – All Rights Reserved

JOHN WYMER Jim Rose Copyright © British Academy 2007 – all rights reserved John James Wymer 1928–2006 ON A WET JUNE DAY IN 1997 a party of archaeologists met at the Swan in the small Suffolk village of Hoxne to celebrate a short letter that changed the way we understand our origins. Two hundred years before, the Suffolk landowner John Frere had written to the Society of Antiquaries of London about flint ‘weapons’ that had been dug up in the local brickyard. He noted the depth of the strata in which they lay alongside the bones of unknown animals of enormous size. He concluded with great prescience that ‘the situation in which these weapons were found may tempt us to refer them to a very remote period indeed; even beyond that of the present world’.1 Frere’s letter is now recognised as the starting point for Palaeolithic, old stone age, archaeology. In two short pages he identified stone tools as objects of curiosity in their own right. But he also reasoned that because of their geological position they were ‘fabricated and used by a people who had not the use of metals’.2 The bi-centenary gathering was organised by John Wymer who devoted his professional life to the study of the Palaeolithic and whose importance to the subject extended far beyond a brickpit in Suffolk. Wymer was the greatest field naturalist of the Palaeolithic. He had acute gifts of observation and an attention to detail for both artefacts and geol- ogy that was unsurpassed. He provided a typology and a chronology for the earliest artefacts of Britain and used these same skills to establish 1 R. -

The Mesolithic Settlement of Sindh (Pakistan): a Preliminary Assessment

PRAEHISTORIA vol. 4–5 (2003–2004) THE MESOLITHIC SETTLEMENT OF SINDH (PAKISTAN): A PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT Paolo BIAGI* Abstract The discovery of Mesolithic sites in Upper and Lower Sindh is of fundamental importance for the study of the Early Holocene communities that inhabited the territory around the beginning of the Holocene. Microlithic chipped stone assemblages have been discovered in two distinct regions: the Thar Desert of Upper Sindh, and along the coast of the Arabian Sea and on the terraces of the rivers that flow into it, around the Karachi Gulf (Lower Sindh). The variable characteristics of the chipped stone assemblages seem to indicate different chronological periods of habitation and models of exploitation of the natural resources. Due to the rarity of organic material, only one Lower Sindh site has been so far radiocarbon-dated. The typological analysis of the assemblages, currently under way, will lead to a more detailed definition of the periods represented at the different sites. At present the only parallels can be extended to the microlithic sites of Rajastan and Gujarat, in India, a few of which consist of radiocarbon-dated, stratified settlements. Preface and many other sites, mainly located along the banks of the streams that flow into the Arabian During the last thirty years, our knowledge of Sea in Lower Sindh (Khan 1979a) (Fig. 1). the Mesolithic of Sindh has greatly increased, thanks to the new discoveries made in the Thar The Mesolithic of the Indian Subcontinent is Desert, along the southernmost fringes of the still an argument of debate by several authors. Rohri Hills in Upper Sindh (Biagi & Veesar For instance G. -

Chert Artefacts and Structures During the Final Mesolithic at Garvald Burn, Scottish Borders Torben Bjarke Ballin and Chris Barrowman

ARO15: Chert artefacts and structures during the final Mesolithic at Garvald Burn, Scottish Borders Torben Bjarke Ballin and Chris Barrowman Archaeology Reports Online, 52 Elderpark Workspace, 100 Elderpark Street, Glasgow, G51 3TR 0141 445 8800 | [email protected] | www.archaeologyreportsonline.com ARO15: Chert artefacts and structures during the final Mesolithic at Garvald Burn, Scottish Borders Published by GUARD Archaeology Ltd, www.archaeologyreportsonline.com Editor Beverley Ballin Smith Design and desktop publishing Gillian McSwan Produced by GUARD Archaeology Ltd 2015. ISBN: 978-0-9928553-4-5 ISSN: 2052-4064 Requests for permission to reproduce material from an ARO report should be sent to the Editor of ARO, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the ARO Reports series rests with GUARD Archaeology Ltd and the individual authors. The maps are reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. All rights reserved. GUARD Archaeology Licence number 100050699. The consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, advertising or promotional purposes, the creation of new collective works or resale. Torben Bjarke Ballin Lithic Research, Stirlingshire Honorary Research Fellow, University of Bradford Chris Barrowman Western Isles Heritage Management Field Officer, Historic Scotland Contents Abstract 6 Introduction 6 Aims and objectives 6 Project history 6 The location 7 The site investigation 9 Fieldwalking -

The Palaeolithic Occupation of Europe As Revealed by Evidence from the Rivers: Data from IGCP 449

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by EPrints Complutense The Palaeolithic occupation of Europe as revealed by evidence from the rivers: data from IGCP 449 DAVID R. BRIDGLAND,h PIERRE ANTOINE/ NICOLE LlMONDIN-LOZOUET/ JUAN I. SANTISTEBAN/ ROB WESTAWAy4t and MARK J. WHITEs 1 Department of Geography, University of Durham, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 2 UMR CNRS 8591-Laboratoire de Geographie Physique, 1 Place Aristide Briand, 92195 Meudon cedex, France 3 Departamento Estratigraffa, Facultad Ciencias Geol6gicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Calle Jose Antonio Novais 2, 28040 Madrid, Spain 4 Faculty of Mathematics and Computing, The Open University, Eldon House, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 3PW, UK 5 Department of Archaeology, University of Durham, Durham DH1 3LE, UK ABSTRACT: IGCP 449 (2000-2004), seeking to correlate fluvial records globally, has compiled a dataset of archaeological records from Pleistocene fluvial sequences. Many terrace sequences can now be reliably dated and correlated with marine oxygen isotope stages (M IS), allowing potentially useful patterns in artefact distribution to be recognised. This review, based on evidence from northwest European and German sequences (Thames, Somme, Ilm, Neckar and Wipper), makes wider comparisons with rivers further east, particularly the Vltava, and with southern Europe, especially Iberia. The northwest and southern areas have early assemblages dominated by handaxes, in contrast with flake-core industries in Germany and further east. Fluvial sequences can provide frameworks for correlation, based on markers within the Palaeolithic record. In northwest Europe the first appearance of artefacts in terrace staircases, the earliest such marker, dates from the mid-late Cromerian Complex.