The Cost of Doing Nothing: Maritime Infrastructure Vulnerabilities in an Emerging Arctic”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SILURIAN TIMES NEWSLETTER of the INTERNATIONAL SUBCOMMISSION on SILURIAN STRATIGRAPHY (ISSS) (INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION on STRATIGRAPHY, ICS) No

SILURIAN TIMES NEWSLETTER OF THE INTERNATIONAL SUBCOMMISSION ON SILURIAN STRATIGRAPHY (ISSS) (INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON STRATIGRAPHY, ICS) No. 27 (for 2019) Edited by ZHAN Renbin INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES President: CHENG Qiuming (Canada) Vice-Presidents: Kristine ASCH (Germany) William CAVAZZA (Italy) Secretary General: Stanley C. FINNEY (USA) Treasurer: Hiroshi KITAZATO (Japan) INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON STRATIGRAPHY Chairman: David A.T. HARPER (UK) Vice-Chairman: Brian T. HUBER (USA) Secretary General: Philip GIBBARD (UK) SUBCOMMISSION ON SILURIAN STRATIGRAPHY Chairman: Petr ŠTORCH (Czech Republic) Vice-Chairman: Carlo CORRADINI (Italy) Secretary: ZHAN Renbin (China) Other titular members: Anna ANTOSHKINA (Russia) Carlton E. BRETT (USA) Bradley CRAMER (USA) David HOLLOWAY (Australia) Jisuo JIN (Canada) Anna KOZŁOWSKA (Poland) Jiří KŘÍŽ (Czech Republic) David K. LOYDELL (UK) Peep MÄNNIK (Estonia) Michael J. MELCHIN (Canada) Axel MUNNECKE (Germany) Silvio PERALTA (Argentina) Thijs VANDENBROUCKE (Belgium) WANG Yi (China) Živilė ŽIGAITĖ (Lithuania) Silurian Subcommission website: http://silurian.stratigraphy.org 1 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S CORNER 3 ANNUAL REPORT OF SILURIAN SUBCOMMISSION FOR 2019 7 INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON STRATGRAPHY STATUTES 15 REPORTS OF ACTIVITIES IN 2019 25 1. Report on the ISSS business meeting 2019 25 2. Report on the 15th International Symposium on Early/Lower Vertebrates 28 3. Report on the 13th International Symposium on the Ordovician System in conjunction with the 3rd Annual Meeting of IGCP 653 32 GUIDELINES FOR THE ISSS AWARD: KOREN' AWARD 33 ANNOUNCEMENTS OF MEETINGS and ACTIVITIES 34 1. Lithological Meeting: GEOLOGY OF REEFS 34 SILURIAN RESEARCH 2019: NEWS FROM THE MEMBERS 36 RECENT PUBLICATIONS ON THE SILURIAN RESEARCH 67 MEMBERSHIP NEWS 77 1. List of all Silurian workers and interested colleagues 77 2. -

Icesat-Derived Elevation Changes on the Lena Delta and Laptev Sea, Siberia

Open Journal of Modern Hydrology, 2014, 4, 1-9 Published Online January 2014 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojmh) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojmh.2014.41001 ICESat-Derived Elevation Changes on the Lena Delta and Laptev Sea, Siberia Reginald R. Muskett Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, USA. Email: [email protected] Received November 19th, 2013; revised December 5th, 2013; accepted December 12th, 2013 Copyright © 2014 Reginald R. Muskett. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accor- dance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Reginald R. Muskett. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. ABSTRACT We employ elevation data from the Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) Geoscience Laser Altimeter System (GLAS) to investigate surface changes across the Lena Delta and sea ice of the coastal Laptev Sea, Sibe- ria during winters of 2003 through 2008. We compare ICESat GLAS-derived elevation changes on sea ice and the Bykovskaya and Sardakhskaya Channels with datum-corrected tide gauge height measurements from Danai, Sannikova and Tiksi stations. We find the coastal sea ice and large inland ice covered channels elevation changes are in phase with the tide-height changes on a same month-year and datum-controlled basis. Furthermore, we find elevation change on tundra drained lake basins to be +0.03 ± 0.02 m, on average. -

LATE PLEISTOCENE and EARLY HOLOCENE WINTER AIR TEMPERATURES in KOTELNY ISLAND: RECONSTRUCTIONS USING STABLE ISOTOPES of ICE WEDGES Yu.K

Kriosfera Zemli, 2019, vol. XXIII, No. 2, pp. 12–24 http://www.izdatgeo.ru DOI: 10.21782/EC2541-9994-2019-2(12-24) LATE PLEISTOCENE AND EARLY HOLOCENE WINTER AIR TEMPERATURES IN KOTELNY ISLAND: RECONSTRUCTIONS USING STABLE ISOTOPES OF ICE WEDGES Yu.K. Vasil’chuk1,2, V.M. Makeev3, A.A. Maslakov1, N.A. Budantseva1, A.C. Vasil’chuk1 1 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Faculty of Geography and Faculty of Geology, 1, Leninskie Gory, Moscow, 119991, Russia 2 Tyumen State University, 6, Volodarskogo str., Tyumen, 625003, Russia; [email protected] 3Russian State Hydrometeorological University, 98, Malookhtinsky prosp., St. Petersburg, 109017, Russia Late Pleistocene and Holocene winter air temperatures in Kotelny Island, northeastern Russian Arctic, have been reconstructed using oxygen isotope compositions of ice wedges and correlated with evidence of Late Pleistocene and Holocene climate variations inferred from pollen data. The δ18О values range exceeds 6 ‰ in Late Pleistocene ice wedges but is only 1.5 ‰ in the Holocene ones (–30.6 ‰ to –24.0 ‰ against –23.1 ‰ to –21.6 ‰, respectively). The Late Pleistocene mean January air temperatures in Kotelny Island were 10–12 °С lower than the respective present temperature. On the other hand, mean winter temperatures in cold substages during the Karga interstadial were colder than those during the Sartan glacial event. The Late Pleistocene– Holocene climate history included several warm intervals when air temperatures were high enough to maintain the existence of low canopy tree patches in Kotelny Island. Mean January air temperatures in the early Holocene were only 1.0–1.5 °С lower than now. -

Aalenian Stage, Jurassic, 209 Absolute Plate Motion, 36 Acadian

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10532-4 — Earth History and Palaeogeography Trond H. Torsvik , L. Robin M. Cocks Index More Information Index Aalenian Stage, Jurassic, 209 Andrarum Limestone, Sweden, 100 Austrazean brachiopod Province, 192 absolute plate motion, 36 Angara Massif, Siberia, 99, 135, 172 Avalonia Continent, 41, 51, 90, 112, 128, 141 Acadian Orogeny, 145 Angaran floral Province, 174, 191 Aves Ridge, 48 Acanthostega amphibian, 154 Angayucham Ocean, 146, 186 Axel Heiberg Island, Canada, 44, 203, 253 Acatlán Complex, Mexico, 141 Anisian Stage, Triassic, 196 Achala granite, Argentina, 164 Annamia Continent, 66, 92, 98, 115, 142, 164, Baffin Bay, Canada, 251 Achalian Orogeny, 141 186 Bajocian Stage, Jurassic, 209 acritarchs, 113 Annamia–South China continent, 129 Balkhash–Mongol–Okhotsk Region, 156 Admiralty Granite, Antarctica, 164 Antarctic Circumpolar Current, 254 Baltic Shield, 99 Adria Terrane, 261 Antarctic ice sheet, 272 Baltica Continent, 15, 50, 109 Adriatic promontory, 245 Antarctic Peninsula, 72, 128, 189, 238 Banda Arc, 67 Ægir Ocean, 86, 139 Antarctic Plate, 226 Banda Embayment, 261 Ægir Ridge, 251 Antarctica, 69 Banggi–Sula, Indonesia, 67 Afar LIP, 249, 264, 273 Anti-Atlas Mountains, Morocco, 164 Barbados Prism, 48 Afghanistan, 63, 142 Anticosti Island, Canada, 122, 136 Barents Sea, 44, 52, 184, 201, 251 African Plate, 13 Antler Orogeny, 44, 146 Barguzin Terrane, Siberia, 56, 151 age of the Earth, 77 Anyui, Russian Arctic, 55 Barremian Stage, Cretaceous, 220 Agulhas–Falkland Fracture Zone, 212 Appalachians, 145, -

The Seasonal Cycle and Break-Up of Landfast Sea Ice Along the Northwest Coast of Kotelny Island, East Siberian Sea

Journal of Glaciology The seasonal cycle and break-up of landfast sea ice along the northwest coast of Kotelny Island, East Siberian Sea Article Mengxi Zhai1,2, Bin Cheng2,3 , Matti Leppäranta4, Fengming Hui2,5, Xinqing Li2,5, 6 1 2,5 Cite this article: Zhai M, Cheng B, Leppäranta Denis Demchev , Ruibo Lei and Xiao Cheng M, Hui F, Li X, Demchev D, Lei R, Cheng X (2021). The seasonal cycle and break-up of 1MNR Key Laboratory for Polar Science, Polar Research Institute of China, Shanghai 200136, China; 2State Key landfast sea ice along the northwest coast of Laboratory of Remote Sensing Science, College of Global Change and Earth System Science, Beijing Normal Kotelny Island, East Siberian Sea. Journal of University, Beijing 100875, China; 3Finnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki FI-00101, Finland; 4Institute of Glaciology 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/ Atmosphere and Earth Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki FI-00014, Finland; 5School of Geospatial jog.2021.85 Engineering and Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China and 6Nansen Environmental and Received: 8 November 2020 Remote Sensing Centre (NERSC), Bergen N-5006, Norway Revised: 16 June 2021 Accepted: 21 June 2021 Abstract Key words: Arctic landfast sea ice (LFSI) represents an important quasi-stationary coastal zone. Its evolution Arctic Ocean; ice break-up; landfast sea ice; is determined by the regional climate and bathymetry. This study investigated the seasonal cycle remote sensing; thermodynamic model and interannual variations of LFSI along the northwest coast of Kotelny Island. Initial freezing, Authors for correspondence: rapid ice formation, stable and decay stages were identified in the seasonal cycle based on appli- Xiao Cheng, cation of the visual inspection approach (VIA) to MODIS/Envisat imagery and results from a E-mail: [email protected]; thermodynamic snow/ice model. -

The Biogeochemistry of Lena River: Organic Carbon and Nutrients Distribution

Marine Chemistry 53 (I 996) 2 1I-227 The biogeochemistry of Lena River: organic carbon and nutrients distribution G. Cauwet ‘, I. Sidorov ‘.’ ” Centre National de la Recherche Scientfiyue. Gmupement dr Rrcherchrs lnteractioru Continent-O&n. Ohsewrrtoire OcPanologique. BP 44, 66651 Barguls sur Mer. France h Tiksi Department of Roscomhydmmrt, Akademiku Fedororcr, 27. 678400 Tiksi, Republic Sukha f YcrkutiwL Ruxsitr Received 25 May 1994: accepted 5 January 1995 Abstract The Lena River is one of the most important rivers flowing to the Arctic Ocean. Draining the Siberian forest and tundra, it is characterized by black waters enriched in organic matter. Compared to other Arctic or subarctic rivers, the Lena River is very similar in the content of ammonia, phosphates, organic nitrogen and phosphorus, but three times richer in silica and nitrate. The distribution of POC, DOC, DIC and suspended matter during two cruises in September 1989 and 1991 was comparable and was influenced by the water input from the river. DOC and DIC exhibit a very conservative behaviour to salinity. The TOC discharge, is on a yearly basis directly connected to water discharge with a maximum during the flood time in June-July. From about 330 pM during the low stage period (November to April), the TOC concentration increases up to 1200 pM during the flood. The organic carbon content of suspended matter depends upon the level sampled and decreases with the suspended load. Surface samples range between 4 and 209 while samples collected in bottom waters are less rich (6 to 3%). Waters from the Buor-Khaya Bay are richer (20 to 10%7F). -

Low Body Mass of Juvenile Ross's Gulls Rhodostethia Rosea in the Laptev

ARCTIC VOL. 51, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 1998) P. 280– 282 Low Body Mass of Juvenile Ross’s Gulls Rhodostethia rosea in the Laptev Sea ÅKE LINDSTRÖM,1 STAFFAN BENSCH1 and PAUL ERIC JÖNSSON1 (Received 4 September 1997; accepted in revised form 23 December 1997) ABSTRACT. Four juvenile Ross’s gulls Rhodostethia rosea were trapped on the New Siberian Islands in the Laptev Sea in early August 1994, allowing data collection on body mass and morphometrics from a poorly known part of the species’ annual cycle. The wings of juvenile birds were shorter than those previously reported for adults, but their bill length and tarsus length were similar. Their average body mass (128 g) was very low, suggesting that some juvenile Ross’s gulls have only very small energy reserves left after post-breeding dispersal, which in this case was at least 300 km. Key words: Ross’s gull, Rhodostethia rosea, body mass, morphometrics, post-breeding dispersal, New Siberian Islands, Laptev Sea RÉSUMÉ. Au début d’août 1994, la capture de quatre mouettes rosées (Rhodostethia rosea) juvéniles dans l’archipel de Nouvelle- Sibérie situé dans la mer des Laptev, a permis de recueillir des données morphométriques ainsi que des données sur la masse corporelle d’une partie mal connue du cycle annuel de l’espèce. Les ailes des oiseaux juvéniles étaient plus courtes que celles des adultes mesurées précédemment, mais la longueur de leur bec et de leur tarse étaient identiques. La moyenne peu élevée (128 g) de la masse corporelle suggère que certaines des mouettes rosées juvéniles ne possèdent que de très faibles réserves d’énergie juste après la dispersion qui suit la saison des nids, dispersion qui dans ce cas était d’au moins 300 km. -

POL Volume 2 Issue 16 Back Matter

THE POLAR RECORD INDEX NUMBERS 9—16 JANUARY 1935—JULY 1938 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR THE SCOTT POLAR RESEARCH INSTITUTE CAMBRIDGE: AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1939 THE POLAR RECORD INDEX Nos. 9-16 JANUARY 1935—JULY 1938 The names of ships are in italics. Expedition titles are listed separately at Uie end Aagaard, Bjarne, II. 112 Alazei Mountains, 15. 5 Abruzzi, Duke of, 15. 2 Alazei Plateau, 12. 125 Adams, Cdr. .1. B., 9. 72 Alazei River, 14. 95, 15. 6 Adams, M. B., 16. 71 Albert I Peninsula, 13. 22 Adderley, J. A., 16. 97 Albert Harbour, 14. 136 Adelaer, Cape, 11. 32 Alberta, 9. 50 Adelaide Island, 11. 99, 12. 102, 103, 13. Aldan, 11. 7 84, 14. 147 Aldinger, Dr H., 12. 138 Adelaide Peninsula, 14. 139 Alert, 11. 3 Admiralty Inlet, 13. 49, 14. 134, 15. 38 Aleutian Islands, 9. 40-47, 11. 71, 12. Advent Bay, 10. 81, 82, 11. 18, 13. 21, 128, 13. 52, 53, 14. 173, 15. 49, 16. 15. 4, 16. 79, 81 118 Adytcha, River, 14. 109 Aleutian Mountains, 13. 53 Aegyr, 13. 30 Alexander, Cape, 11. GO, 15. 40 Aerial Surveys, see Flights Alexander I Land, 12. 103, KM, 13. 85, Aerodrome Bay, II. 59 80, 14. 147, 1-19-152 Aeroplanes, 9. 20-30, 04, (i5-(>8, 10. 102, Alcxamtrov, —, 13. 13 II. 60, 75, 79, 101, 12. 15«, 158, 13. Alexcyev, A. D., 9. 15, 14. 102, 15. Ki, 88, 14. 142, 158-103, 16. 92, 93, 94, 16. 92,93, see also unilcr Flights Alftiimyri, 15. -

Military Infrastructure and Strategic Capabilities: Russia's Arctic

Military Infrastructure and Strategic Capabilities 187 Chapter 8 Military Infrastructure and Strategic Capabilities: Russia’s Arctic Defense Posture Ernie Regehr Left to its own internal dynamics, the Arctic should not be drifting towards geostrategic competition and growing tension. While the re- gion’s resource base is significant, no lawless claims rush is brewing, not least because it is not a lawless frontier and because most of those re- sources are within the acknowledged jurisdictions of individual states, either behind national boundaries or inside exclusive economic zones. There are promising fisheries resources in the international Arctic waters beyond national jurisdictions, but commonly agreed restraints and regulations are moving toward the status of law. The borders be- tween states are largely settled, and where they are not, there is really no likelihood that their resolution will involve military confrontation. Continental shelf claims, still being processed at the United Nations, will be adjudicated by scientists, not soldiers, and by the application of established laws—laws which all five Arctic Ocean states have pledged to follow, through the Ilulissat Declaration (even though the United States is not party to the key legal framework, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, UNCLOS).1 Ultimate legal jurisdiction over increasingly navigable sea transportation routes is contested, and while that could lead to symbolic challenges, like freedom of navigation voy- ages, and produce commensurate tensions, no state in the region or beyond has a serious interest in obstructing or disrupting those routes. These are not conditions to drive intense competition. To be sure, Russia is a key Arctic power that is elsewhere in a serious stand-off with its Arctic neighbors through NATO. -

The Seasonal Cycle and Break-Up of Landfast Sea Ice Along the Northwest Coast of Kotelny Island, East Siberian Sea

Journal of Glaciology The seasonal cycle and break-up of landfast sea ice along the northwest coast of Kotelny Island, East Siberian Sea Article Mengxi Zhai1,2, Bin Cheng2,3 , Matti Leppäranta4, Fengming Hui2,5, Xinqing Li2,5, 6 1 2,5 Cite this article: Zhai M, Cheng B, Leppäranta Denis Demchev , Ruibo Lei and Xiao Cheng M, Hui F, Li X, Demchev D, Lei R, Cheng X (2021). The seasonal cycle and break-up of 1MNR Key Laboratory for Polar Science, Polar Research Institute of China, Shanghai 200136, China; 2State Key landfast sea ice along the northwest coast of Laboratory of Remote Sensing Science, College of Global Change and Earth System Science, Beijing Normal Kotelny Island, East Siberian Sea. Journal of University, Beijing 100875, China; 3Finnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki FI-00101, Finland; 4Institute of Glaciology 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/ Atmosphere and Earth Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki FI-00014, Finland; 5School of Geospatial jog.2021.85 Engineering and Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China and 6Nansen Environmental and Received: 8 November 2020 Remote Sensing Centre (NERSC), Bergen N-5006, Norway Revised: 16 June 2021 Accepted: 21 June 2021 Abstract Key words: Arctic landfast sea ice (LFSI) represents an important quasi-stationary coastal zone. Its evolution Arctic Ocean; ice break-up; landfast sea ice; is determined by the regional climate and bathymetry. This study investigated the seasonal cycle remote sensing; thermodynamic model and interannual variations of LFSI along the northwest coast of Kotelny Island. Initial freezing, Authors for correspondence: rapid ice formation, stable and decay stages were identified in the seasonal cycle based on appli- Xiao Cheng, cation of the visual inspection approach (VIA) to MODIS/Envisat imagery and results from a E-mail: [email protected]; thermodynamic snow/ice model. -

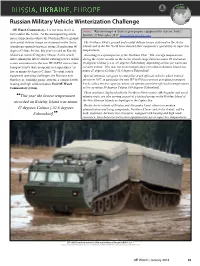

Russian Military Vehicle Winterization Challenge

RUSSIA, UKRAINE, EUROPE Russian Military Vehicle Winterization Challenge OE Watch Commentary: It is not news that it is Source: “Russian troops in Arctic region prepare equipment for extreme frosts,” very cold in the Arctic. As the accompanying article Interfax, 29 November 2017. http://www.interfax.com notes, temperatures where the Northern Fleet’s ground and coastal defense troops are stationed on the Arctic The Northern Fleet’s ground and coastal defense troops stationed on the Arctic islands run routinely between minus 20 and minus 40 islands and in the Far North have checked their equipment’s operability in super low degrees Celsius. In fact, this year’s record on Kotelny temperatures. Island was minus 47 degrees Celsius. As the article According to a spokesperson of the Northern Fleet “The average temperatures notes, among the latest vehicles entering service in this during the winter months on the Arctic islands range between minus 20 and minus severe environment is the new DT-10 PM: two-section 40 degrees Celsius [-4 to -40 degrees Fahrenheit], depending on how far warm sea transport trucks that can operate in temperatures “as currents extend. This year the lowest temperature recorded on Kotelny Island was low as minus 50 degrees Celsius.” To counter such minus 47 degrees Celsius [-52.6 degrees Fahrenheit]. equipment operating challenges, the Russians note Special attention was given to caterpillar-track off-road vehicles which entered that they are building garage structures equipped with service in 2017, in particular the new DT-10 PM two-section articulated transport heating and high wind-resistance End OE Watch trucks with a ten-ton capacity, which can operate anywhere off-road in temperatures Commentary (Grau) as low as minus 50 degrees Celsius [-58 degrees Fahrenheit]. -

Tectonic Subdivision of the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas

RUSSIAN JOURNAL OF EARTH SCIENCES, VOL. 5, NO. 3, PAGES 185–202, JUNE 2003 Tectonic subdivision of the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas A. O. Mazarovich and S. Yu. Sokolov Geological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences (GIN RAS) Abstract. A tentative tectonic subdivision for the Chukchi and East Siberian seas has been created based on the processing and analysis of new satellite altimetry and magnetic data and published materials that include information in electronic formats. The Chukchi Sea shelf is composed of correlatives of the Alaskan tectonic zones. The main Alaskan thrust does not stretch into Wrangel Island but is instead located in the region of the South Chukchi Sea Basin. Most part of the shelf is occupied by a zone of zero or slight deformation. The North Chukchi Sea Basin along with the Vilkitsky Trough and the region of maximum subsidence in the Colville Trough make a single entity, the Novosibirsk–Alaska Basin. Introduction other (Canada Basin) topographically uniform [Naryshkin, 2001]. The former accommodates the Lomonosov Ridge and the Alpha, Mendeleev, Chukchi, and Northwind rises, which are linked with the Podvodnikov, Makarov, Stefans- The Arctic shelves of Russia became a focus of keen at- son, Mendeleev, Chukchi, and Northwind basins. All these tention after large hydrocarbon fields had been discovered in morphostructures trend roughly N–S and are truncated by the Barents and Kara seas and on land directly adjacent to the shelf edge. The Chukchi and East Siberian seas are un- the Laptev and Beaufort seas. In recent years, this has pro- derlied with continental crust 30–35 km thick in the transi- vided an incentive to create and publish new tectonic maps tion between the North American and Eurasian lithospheric for all the Arctic seas of Russia, except for the East Siberian plates [Bird, 1999].