Bihar Education Project (Sitamarhi)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India: Patna (Bihar) Hospital PPP

Public-Private Partnership Impact Stories India: Patna (Bihar) Hospital PPP Located in eastern India, Bihar is a low income state (LIS) with around 104 million people. According to the Government of India (GoI), over half the population is Below Poverty Line (BPL). In addition, the public health services in Bihar face severe constraints, especially lack of affordable specialty/tertiary care services. There are substantial gaps in health sector infrastructure and essential health requirements, including qualified staff, equipment, drugs, and consumables. As a result, people in the state have to travel to other states for their treatment. To help the state govern- ment improve access to, and availability of, advanced and affordable healthcare, IFC provided advisory assistance to the Government of Bihar and the state’s Infrastructure Development Authority (IDA), to structure and implement a public-private partner- ship (PPP) aimed at building, operating, and maintaining a greenfield super-specialty hospital in Patna, the capital city of the State of Bihar. The project was awarded on a competitive bid process to Global Health Patliputra Private Limited (GHPPL), a unit of Medanta the Medicity, one of India’s largest multi- super specialty hospitals. The concession agreement was signed with GHPPL on 22nd August 2015. The developer will develop the 500 bed super specialty hospital on Design, Build, Finance, Operate, & Transfer (DBFOT)) basis for a concession period of 33 years. This series provides an overview of public-private partnership stories in various infrastructure sectors, where IFC was the lead advisor. IFC’s advisory work was undertaken with financial support from the IFC Advisory Services in Public-Private Partnerships HANSHEP Health PPP facility funded by the UK’s Department for In- 2121 Pennsylvania Ave. -

Constituency-Wise Information on Inclusion and Deletions in Current Electoral Over Previous Roll

ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Format 4B Format 4B (With CEO) Constituency-wise Information on Inclusion and Deletions in Current Electoral Over Previous Roll Name of State: BIHAR Net % Total claims lodged in Total Objections Lodged in Suo-moto Deletion Electors as per proposed Final change Change Electors as per Draft Roll w.r.t. Total Deletions subsequent Assembly Constituency Form 6 after draft Total Claims admitted Form 7 after draft publication Total Objections admitted subsenquent to last Number of Deletions Due to Roll w.r.t. 01.01.2021 as the over over 01.01.2021 as the qualifying date to last publication of roll publication of roll of roll pulication of roll qualifying date previous previuos Final roll Final roll Third Third Third Third Third Third Third Third No Name Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Expired Shifted Repeated Male Female (+/-) (+/-) Gender Gender Gender Gender Gender Gender Gender Gender 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 Valmiki Nagar 178264 153489 34 6317 5476 3 85 60 0 0 0 0 85 60 0 85 60 0 184499 158902 37 11651 3.39 2 Ramnagar (SC) 155977 139899 10 3372 2676 0 46 28 0 0 0 0 46 28 0 0 1 62 159305 142545 10 5974 1.98 3 Narkatiaganj 141813 123638 16 3340 2798 1 345 296 0 0 0 0 345 296 0 468 80 70 144815 126133 17 5498 2.03 4 Bagaha 162404 142895 15 4055 3721 1 142 155 0 0 0 0 142 155 0 147 25 121 166316 146462 16 7480 2.39 5 Lauriya 137451 118586 11 1999 1647 0 87 68 0 0 0 0 87 68 0 96 28 29 139363 120165 11 3491 -

Revised Centre List of TDC Part

Revised Centre List of T.D.C. Part - IInd & IIIrd Practical Examination - 2016 Date of Examination: From 22.04.2017 onwards Sl. Name of Centre Subjects Name of Colleges No. 1. L.S. College, PHY, CHE, BOT, ZOO, 1. L.S. College, Muzaffarpur Muzaffarpur ELECTRONICS and 2. R.B.B.M. College, Muzaffarpur only Sc. PSY. 3. J.B.S.D. College, Bakuchi only Sc. & PSY 4. All Const. & Affiliated Colleges under the jurisdiction of BRABU, Muzaffarpur only Elect. 2. R.D.S. College, PHY, CHE, BOT, ZOO, 1. R.D.S. College, Muzaffarpur Muzaffarpur PSY and, GEO. 2. R.C. College, Sakra only GEO 3. R.S. College, Muz only GEO 4. L.N.T. College, Muz.- SC, PSY & GEO 5. S.R.P.S. College, Jaitpur – PSY & SC 6. Remaining all Coll. of Muz., Sitamarhi District only GEO. 3 M.D.D.M. College, PHY, CHE, BOT, ZOO, 1. M.D.D.M. College, Muz. Muzaffarpur PSY, HSC, GEO & 2. M.S.K.B. College, Muz. Only Sc. MUSIC. 3. L.N.T. College, Muz. Only HSC. 4. All Constituent & Affiliated Colleges of Muzaffarpur, Sitamarhi, Vaishali Distt. only Music, 4 R.B.B.M., College, PSY, HSC 1. R.B.B.M. College, Muz. Muzaffarpur 2. J. College, Motipur, only HSC. 3. C.N. College Sahebganj only HSC 5. M.S.K.B. College, PSY, HSC 1. M.S.K.B. College, Muzaffarpur Muzaffarpur 6. Niteshwar College, PHY, CHE, BOT, ZOO, 1. Niteshwar College, Muzaffarpur Muzaffarpur PSY, HSC, GEO 2. Dr. R.M.L.S. College, Muz only SC. -

Ground Water Year Book, Bihar (2015 - 2016)

का셍ााल셍 उप셍ोग हेतू For Official Use GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD जल ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पूर्वी क्षेत्र, पटना सितंबर 2016 MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA September 2016 ` GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES जल CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पर्वू ी क्षेत्र, पटना MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA सितंबर 2016 September 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) CONTENTS CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables i List of Figures ii List of Annexures ii List of Contributors iii Abstract iv 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................1 2. HYDROGEOLOGY..........................................................................................................1 3. GROUND WATER SCENARIO......................................................................................4 3.1 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL........................................................................................8 3.1.1 MAY 2015.....................................................................................................................8 3.1.2 AUGUST 2015..............................................................................................................10 3.1.3 NOVEMBER 2015........................................................................................................12 3.1.4 JANUARY 2016...........................................................................................................14 -

Situation Report - Bihar Floods

SITUATION REPORT - BIHAR FLOODS NAME OF THE DISASTER: FLOODS DATE: 15.07.04 at 7:30 PM Rain in the upper catchment areas of Nepal has resulted in the rise of the water levels of all the major rivers of Bihar and so far 16 districts (out of a total of 38 districts) have been affected by the flood waters. 11.128 million people are affected by the unprecedented floods in Darbhanga, Madhubhani, Sitamarhi, Sheohar and East Champaran Districts. Situation is grim with continuous rains over the northern portion of the state and is likely to get critical with rain/thundershowers forecasted over Bihar by the Indian Meteorological department. As per the Central Water Commission report, river Kamala Balan, Budhi Gandak, Bagmati, Kosi, Mahananda and Adhwara group of rivers are flowing above the danger level. The districts so far affected are Supaul, Darbhanga, Bhagalpur, W.Champaran, Muzaffarpur, Sitamarhi, Khagaria , Sheohar, Madhubani, Araria, Saharsa , E. Champaran, Katihar, Kishanganj & Samastipur. The worst affected districts are Darbhanga, Sheohar, Madhubani and Sitamarhi. Sitamarhi, Darbhanga & Sheoher districts are cut off from the state head quarter.In many districts Rail & Road communications are also cut off. DAMAGES DETAILS: No. of District Affected 16 No. of Block Affected 127 No. of Panchayat affected 1529 No. of Villages affected 4889 Flood Affected Area 4.3253 million Hect. Population affected 11.128 million No of Human lives lost 41 No. of Cattle lives lost 557 No of house damages 283225 Estimated value of damage to houses 24.056 million Rs. Estimated value of damage of public properties 43.63 million Rs. -

District Health Society, Sheohar Sadar Hospital Campus, Sheohar (Bihar) Pin – 843329, Phone : 06222 - 259292 0

District Health Action Plan 2012-2013 District Health Society, Sheohar Sadar Hospital Campus, Sheohar (Bihar) Pin – 843329, Phone : 06222 - 259292 0 Table of contents Foreword About the Profile CHAPTER 1- INTRODUCTION - Page 4 to 7 1.1 Background 1.2 Objectives of the process 1.3 Process of Plan Development 1.3.1 Preliminary Phase 1.3.2 Main Phase - Horizontal Integration of Vertical Programmes 1.3.3 Preparation of DHAP CHAPTER 2- DISTRICT PROFILE - Page 8 to 31 2.1 History 2.2 Geographic Location 2.3 Demographics 2.4 Administrative Units & Towns 2.5 Population at a Glance 2.6 Comparative Population 2.7 District Profile 2.8 Health Facilities in the District 2.9 Human Resource & Infrastructure 2.10 Equipments 2.11 Rogi Kalyan Samiti 2.12 Support System 2.13 Health Services 2.14 Community Participation 2.15 Training Activities 2.16 BCC Campaigns 2.17 District and Block Level Management 2.18 Health Care Institutions in the District CHAPTER 3- SITUATION ANALYSIS- Page 32 to 40 3.1 Gaps in infrastructure 3.2 Health Sub Centre (HSC) 3.3 Additional PHC (APHC) 3.4 Primary Health Centre 3.5 Sadar Hospital CHAPTER 4 – Setting Objectives and suggested plan of Action – Page -41 to 82 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Targeted objective and suggested strategies 4.3 Meternal Health 4.4 Child Health 4.5 Family Planning 4.6 Institutional strengthening Part- A Programme wise Budget Part- B Programme wise Budget Part- C Programme wise Budget Vitamin A Mamta IDD IDSP VBDCP (Kala-Azar) 1 Foreword Recognizing the importance of Health in the process of economic and social development and improving the quality of life of our citizens, the Government of India has resolved to launch the National Rural Health Mission to carry out necessary architectural correction in the basic health care delivery system . -

MAPPING of INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS in Muzaffarpur, Bihar

Study Report Study Report MAPPING OF INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN Muzaffarpur, Bihar Participatory Research in Asia Content Content Page A General Profile of Muzaffarpur City 2 A General Poverty Profile of Muzaffarpur City 3 Methodology for Listing of Informal Settlements 5 Status of Informal Settlements in Muzaffarpur 5 Challenges and Lessons Learned 12 Annexures Annex.1: Format for Listing of Informal Settlements 14 Annex. 2: List of informal Settlements 16 List of Charts and Figures Chart 1: Decadal Population Growth of Muzaffarpur City 2 Chart 2: Status of Informal Settlements in Muzaffarpur 6 Chart 3: Ownership of Informal Settlement Lands in Muzaffarpur 6 Chart 4: Surrounding Areas of Informal Settlements in Muzaffarpur 7 Chart 5: Type of Physical Location of Informal Settlements in Muzaffarpur 7 Chart 6: Locational Characteristics of Informal Settlements in Muzaffarpur 8 Chart 7: Type of Structures for Majority of Houses in Informal Settlements of Muzaffarpur 8 Chart 8: Approach Road to the Informal Settlements in Muzaffarpur 9 Chart 9: Type of Internal Roads in the Informal Settlements of Muzaffarpur 9 Chart 10: Distance from Nearest Motorable Road for Informal Settlements in Muzaffarpur 10 Chart 11: Presence of Public Institutions in the Informal Settlements of Muzaffarpur 11 Chart 12: Presence of CBOs in the Informal Settlements of Muzaffarpur 11 Chart 13: Presence of NGO Projects in the Informal Settlements of Muzaffarpur 12 Figure 1: Map of Muzaffarpur City Showing All the Wards 3 Figure 2: Map of Muzaffarpur City Showing the Locations of Informal Settlements 4 1 Study Report A General Profile of Muzaffarpur City Muzaffarpur, “the Land of Leechi” was created in 1860s for administrative convenience by splitting up the erstwhile district of Tirhut. -

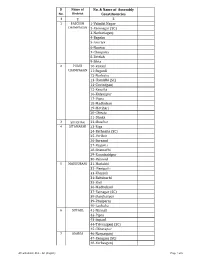

AC with District Dist

Sl Name of No. & Name of Assembly No. District Constituencies 1 2 3 1 PASCHIM 1-Valmiki Nagar CHAMPARAN 2-Ramnagar (SC) 3-Narkatiaganj 4-Bagaha 5-Lauriya 6-Nautan 7-Chanpatia 8-Bettiah 9-Sikta 2 PURVI 10-Raxaul CHAMPARAN 11-Sugauli 12-Narkatia 13-Harsidhi (SC) 14-Govindganj 15-Kesaria 16-Kalyanpur 17-Pipra 18-Madhuban 19-Motihari 20-Chiraia 21-Dhaka 3 SHEOHAR 22-Sheohar 4 SITAMARHI 23-Riga 24-Bathnaha (SC) 25-Parihar 26-Sursand 27-Bajpatti 28-Sitamarhi 29-Runnisaidpur 30-Belsand 5 MADHUBANI 31-Harlakhi 32- Benipatti 33-Khajauli 34-Babubarhi 35-Bisfi 36-Madhubani 37-Rajnagar (SC) 38-Jhanjharpur 39-Phulparas 40-Laukaha 6 SUPAUL 41-Nirmali 42-Pipra 43-Supaul 44-Triveniganj (SC) 45-Chhatapur 7 ARARIA 46-Narpatganj 47-Raniganj (SC) 48-Forbesganj AC with district Dist. - AC (English) Page 1 of 6 Sl Name of No. & Name of Assembly No. District Constituencies 1 2 3 49-Araria 50-Jokihat 51-Sikti 8 KISHANGANJ 52-Bahadurganj 53-Thakurganj 54-Kishanganj 55-Kochadhaman 9 PURNIA 56-Amour 57-Baisi 58-Kasba 59-Banmankhi (SC) 60-Rupauli 61-Dhamdaha 62-Purnia 10 KATIHAR 63-Katihar 64-Kadwa 65-Balrampur 66-Pranpur 67-Manihari (ST) 68-Barari 69-Korha (SC) 11 MADHEPURA 70-Alamnagar 71-Bihariganj 72-Singheshwar (SC) 73-Madhepura 12 SAHARSA 74-Sonbarsha (SC) 75-Saharsa 76-Simri Bakhtiarpur 77-Mahishi 13 DARBHANGA 78-Kusheshwar Asthan (SC) 79-Gaura Bauram 80-Benipur 81-Alinagar 82-Darbhanga Rural 83-Darbhanga 84-Hayaghat 85-Bahadurpur 86-Keoti 87-Jale 14 MUZAFFARPUR 88-Gaighat 89-Aurai 90-Minapur 91-Bochaha (SC) 92-Sakra (SC) 93-Kurhani 94-Muzaffarpur 95-Kanti 96-Baruraj AC with district Dist. -

Bangladesh: Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” Seek Recognition, Respect and Rights Bangladesh: Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” Seek Recognition, Respect and Rights

BANGLADESH: URDU-SPEAKING “BIHARIS” SEEK RECOGNITION, RESPECT AND RIGHTS BANGLADESH: URDU-SPEAKING “BIHARIS” SEEK RECOGNITION, RESPECT AND RIGHTS International Republican Institute IRI.org @IRIglobal © 2020 All Rights Reserved Bangladesh: Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” Seek Recognition, Respect and Rights Copyright © 2020 International Republican Institute. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the International Republican Institute. Requests for permission should include the following information: • The title of the document for which permission to copy material is desired. • A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. • The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. • Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, e-mail address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: Attn: Department of External Affairs International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] Cover Image Description: Aerial view of the Biharis Relief Camp, known as the “Geneva Camp.” IRI | BANGLADESH • Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” 3 OVERVIEW In early 2020, the International Republican Institute (IRI) conducted a qualitative research study of the Bihari community in Bangladesh — an Urdu-speaking linguistic minority group in the South Asian nation. The study examined the challenges and needs of Biharis in different locations around Bangladesh. The term “Bihari” refers to approximately 300,000 non-Bengali, Urdu-speaking citizens of Bangladesh who came to what was then East Pakistan mostly from the Indian states of Bihar and West Bengal after the Partition of India in 1947. -

Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES* (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______ SUBMISSION BY MEMBERS Re: Farmers facing severe distress in Kerala. THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI RAJ NATH SINGH) responding to the issue raised by several hon. Members, said: It is not that the farmers have been pushed to the pitiable condition over the past four to five years alone. The miserable condition of the farmers is largely attributed to those who have been in power for long. I, however, want to place on record that our Government has been making every effort to double the farmers' income. We have enhanced the Minimum Support Price and did take a decision to provide an amount of Rs.6000/- to each and every farmer under Kisan Maan Dhan Yojana irrespective of the parcel of land under his possession and have brought it into force. This * Hon. Members may kindly let us know immediately the choice of language (Hindi or English) for obtaining Synopsis of Lok Sabha Debates. initiative has led to increase in farmers' income by 20 to 25 per cent. The incidence of farmers' suicide has come down during the last five years. _____ *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 1. SHRI JUGAL KISHORE SHARMA laid a statement regarding need to establish Kendriya Vidyalayas in Jammu parliamentary constituency, J&K. 2. DR. SANJAY JAISWAL laid a statement regarding need to set up extension centre of Mahatma Gandhi Central University, Motihari (Bihar) at Bettiah in West Champaran district of the State. 3. SHRI JAGDAMBIKA PAL laid a statement regarding need to include Bhojpuri language in Eighth Schedule to the Constitution. -

Block: Piro Class-6-8 Subject: Social Science Dist:-Bhojpur Provisional Merit List Block Teacher Niyojan-2019-20

BLOCK TEACHER NIYOJAN-2019-20 BLOCK: PIRO CLASS-6-8 SUBJECT: SOCIAL SCIENCE DIST:-BHOJPUR PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 MATRIC INTER GRADUATION TRAINING FREE BTET/CT WEIG SUM OF AVG OF TAGE APPL.S. NAME OF SE D. FUL MARK ET TOTAL S.N. FATHER DOB ADDRESS CAT DIS. MARKS MARKS FULL MARKS FULL FULL PERCENT PERCEN OF REMARKS N. APPLICANT X FIGH L S MARKS MERIT OBTAI %GE OBTAIN MARK %GE OBTAINE MARK %GE MARK %GE AGE TAGE BTET/ T. MAR OBTAI % NED ED S D S S CTET KS NED MOHD ARANGI-01 NAZIA 1 1776 MONIR 18/4/1995 F USIA UR N N 457 500 91.4 434 600 72.3333 3330 4500 74 1675 2000 83.75 321.4833 80.37 62.66 2 82.371 MONIR ANSARI GHAZIPUR DAYASHAN PRAGYA KAILASHPUR 2 P/197 KAR 22/12/1996 F EWS N N 409 500 81.8 432 500 86.4 740 1000 74 762 1000 76.2 318.4 79.60 68 2 81.6 PANDEY I BUXAR PANDEY NEERAJ BHRIGUNA BIHIYA 3 976 KUMAR 02.01.1993 M UR N N 403 500 80.6 413 500 82.6 964 1500 64.2667 1064 1300 81.8462 309.3128 77.33 72.41 4 81.328 TH MISHRA BHOJPUR MISHRA SHREE DEVRADH, SUNITA 4 1785 DHAR 03.01.1986 F TIYAR, EWS N N 537 700 76.7143 683 900 75.8889 1179 1500 78.6 1054 1300 81.0769 312.2801 78.07 55.33 2 80.07 KUMARI DUBEY BHOJPUR VIPUL NAWAL GAUSGANJA 5 1770 KUMAR KISHOR 01.04.1979 M UR N N 711 900 79 693 900 77 1177 1500 78.4667 1834 2400 76.4167 310.8833 77.72 62.66 2 79.721 RA SINGH SINGH DHAMANIA, HIMANSHU RAMESHW 6 424 26/01/1996 M GARAHANI, EBC N N 419 500 83.8 350 500 70 722 1000 72.2 998 1300 76.7692 302.7692 75.69 70.67 4 79.692 SHEKHAR AR PRASAD BHOJPUR ROHAI, ASHWANI -

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies Prognosis of Human Rights and Child Trafficking in Bihar

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies ISSN NO:: 2348 – 537X Prognosis of Human Rights and Child Trafficking in Bihar: A Sociometric Analysis Nikhat Shama Research Scholar, Department of Political Science Jamia Millia Islamia , New Delhi ABSTRACT: Human trafficking, or trafficking in persons, is a form of modern-day slavery and millions of people around the world, including children are victims of this crime (DeStefano, 2007).Violations of human rights are both a cause and a consequence of human trafficking (Robinson, 2002). Every country in the world is affected by human trafficking, whether as a country of origin, transit, or destination, and commonly, as all three. Human trafficking is not just a problem in other countries; cases of human trafficking have also been reported in India, which shares a large border with Nepal and Bangladesh. Under the garb of migration, the traffickers have become active and a large number of young girls are being trafficked from both Bangladesh and Nepal to various places in India, especially to Kolkata, Mumbai and Delhi. Despite increased attention and response to the topic of human trafficking, the empirical state of the literature has seen only marginal developments over time, leaving the magnitude of the problem unknown.The literature on trafficking reflects the dilemma of writing on a subject that is not easy to research and document and yet is too grave an issue to ignore. Considering the hidden and criminal nature of the problem, the data presented by most reports is valuable in face of this scarcity. While the adopted definitions, perspectives and approaches to the problem of trafficking may vary the concern with finding effective solutions is common to these studies.