Children's Learning from Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Articles Faculty Scholarship 1996 The Inevitable Wasteland: Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay 1997 Survey of Books Relating to the Law: Legal Regulation and Reform Ronald J. Krotoszynski Jr. University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles Recommended Citation Ronald J. Krotoszynski Jr., The Inevitable Wasteland: Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay 1997 Survey of Books Relating to the Law: Legal Regulation and Reform, 95 Mich. L. Rev. 2101 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles/220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. THE INEVITABLE WASTELAND: WHY THE PUBLIC TRUSTEE MODEL OF BROADCAST TELEVISION REGULATION MUST FAIL Ronald J. Krotoszynski, Jr.* ABANDONED IN THE WASTELAND: CHILDREN, TELEVISION, AND TBE FIRST A~mNDmEr. By Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay. New York: Hill & Wang. 1995. Pp. xi, 237. $11. More than thirty years ago, Newton N. Minow,1 then Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission ("Commission"), scolded broadcasters for failing to meet their obligations to the gen- eral public and, in particular, to the nation's children.2 Minow chal- lenged broadcasters to "sit down in front of your television set when your station goes on the air and stay there.. -

Sesame Street Combining Education and Entertainment to Bring Early Childhood Education to Children Around the World

SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION TO CHILDREN AROUND THE WORLD Christina Kwauk, Daniela Petrova, and Jenny Perlman Robinson SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO Sincere gratitude and appreciation to Priyanka Varma, research assistant, who has been instrumental BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD in the production of the Sesame Street case study. EDUCATION TO CHILDREN We are also thankful to a wide-range of colleagues who generously shared their knowledge and AROUND THE WORLD feedback on the Sesame Street case study, including: Sashwati Banerjee, Jorge Baxter, Ellen Buchwalter, Charlotte Cole, Nada Elattar, June Lee, Shari Rosenfeld, Stephen Sobhani, Anita Stewart, and Rosemarie Truglio. Lastly, we would like to extend a special thank you to the following: our copy-editor, Alfred Imhoff, our designer, blossoming.it, and our colleagues, Kathryn Norris and Jennifer Tyre. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication and research effort was generously provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and The MasterCard Foundation. The authors also wish to acknowledge the broader programmatic support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the LEGO Foundation, and the Government of Norway. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. -

Lightning Strikes Sanibei Serving Pizza at by Jill Tyrer Quick-Thinking Bystanders Rushed to His Aid

AUGUST 12, 1999 VOLUME 26 NUMBER 32 28 PAGES f:-V -159GO€O1OG64O9*CAR~RT SORT R003 """ ' - U SANlBfct LIBRARY d • "(10 O^NLOP KD 33957 SANlHfcL Ft .JORTER GOSS TALKS TO KIWANIS East end home invasion suspect remains at large By Pattie Pace Staff Writer An unidentified man entered the Lindgren Boulevard home of Sanibei woman in her 80s last Saturday and, after tying her hands and feet with a plastic-coated wire and placing a towel over head, fled with approximately $5,000 in jewelry and cash. According to Commander John Terry, the woman was quickly able to free her hands and call police. Officers Jane Cechman and Dave Jalbert arrived on scene within minutes of the call and found the woman in the bedroom. She was bruised and cut from being tied up, but otherwise not physically harmed, according to Terry. The burglar used a stick to poke the woman, but was other- wise unarmed. The officers searched her home and canvassed the neighborhood but could not find the intruder, described as a white male, approximately 40 years old, 5 feel 10 inches tall with a slender build and scraggly, blond chin-length hair. He wore a long-sleeve shirt with faint multicolored thin stripes, long pants, dirty brown work shoes with thick soles and loose untied laces, according to a police press release. » — * • Michael 1'iotdlu Police are asking anyone .who saw a man matching that U.S. Representative Porter Goss listens to a question at the Saiiibel/Captiva.Kiw:a*jiis, CJwb, •""'ctescrlptidn or i suspicion car-in the area of-Lindgren weekly breakfast at the Island House where he was the speaker. -

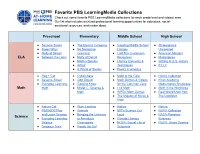

Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections Check out Some Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections for Each Grade Level and Subject Area

Favorite PBS LearningMedia Collections Check out some favorite PBS LearningMedia collections for each grade level and subject area. Our list also includes archived professional learning opportunities for educators, social- emotional resources, and maker ideas. Preschool Elementary Middle School High School ● Sesame Street ● The Electric Company ● Inspiring Middle School ● Shakespeare ● Super Why! ● No Nonsense Literacy Uncovered ● Molly of Denali Grammar ● LGBTQ+ Curriculum ● American Masters ELA ● Between the Lions ● Molly of Denali Resources ● Masterpiece ● Martha Speaks ● Literary Elements & ● Writing in U.S. History ● Arthur Techniques ● It’s Lit ● A World of Stories ● Poetry in America ● Peg + Cat ● Cyberchase ● Math at the Core ● NOVA Collection ● Sesame Street ● Odd Squad ● Math Games & Videos ● Khan Academy ● Everyday Learning: ● Good to Know for the Common Core Mathematics Showcase Math Math ● Mister C: Science & ● I <3 Math ● Math in the Workforce Math ● WPSU Math Games ● Real World Math from ● The Majesty of Music & The Lowdown Math ● Nature Cat ● Plum Landing ● Nature ● Nature ● PBS KIDS Play ● Animals ● MIT's Science Out ● NOVA Collection and Learn Science ● Bringing the Universe Loud ● NASA Planetary Science ● Everyday Learning: to America’s ● Climate Literacy Sciences Science Classrooms ● NOVA: Secret Life of ● NOVA: Gross Science ● Dinosaur Train ● Ready Jet Go! Scientists ● Let’s Go Luna ● All About the Holidays ● Teaching with Primary ● Access World Religions ● Xavier Riddle and ● NY State & Local Source Inquiry Kits -

Opening Worlds of Possibilities for Michiana's Children

Opening Worlds of Possibilities for Michiana’s Children PBS KIDS helps #1 EDUCATIONAL prepare children MEDIA for success in SOURCE school and life PBS aims at making a powerful difference in the lives of America’s children through high-quality, educational content. The number-one children’s educational media brand continues to push boundaries on innovation in teaching and learning across all platforms, including PBSLEARNINGMEDIA.ORG — which provides access to thousands of classroom-ready, curriculum-targeted digital resources such as videos, interactives, documents and in-depth lesson plans. The basic service is free for PreK-12 educators. PBS KIDS offers all children the opportunity to explore new ideas and new worlds through television, online, mobile and community-based programs. Parents, check out PBSPARENTS.ORG for information on child development and early learning through educational games and activities inspired by PBS KIDS programs. PBS provides innovative, cutting-edge platforms that are safe for kids of all ages Go to pbs.org or download your favorite PBS KIDS apps at PBSKIDS.ORG/APPS or by visiting the app stores. NEARLY 90% AGREE PBS IS A SAFE PLACE ONLINE AND ON TV PBS KIDS and The WNIT Kids Club gives kids a chance to WNIT Kids Club fully engage in what Public Television is all about … at a “Kid’s Level”! As an exclusive connect with the member you have the unique opportunity to local community engage with PBS KIDS characters through various events, on-air birthday mentions, discounts and a ton of other fun things. Call to enroll at 574-675-9648, x311. -

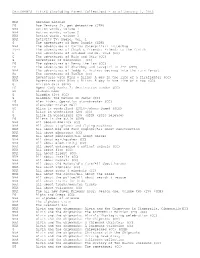

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Menlo Park Juvi Dvds Check the Online Catalog for Availability

Menlo Park Juvi DVDs Check the online catalog for availability. List run 09/28/12. J DVD A.LI A. Lincoln and me J DVD ABE Abel's island J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Ociee Nash J DVD ADV The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin. J DVD ADV The adventures of Pinocchio J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE 2 Agent Cody Banks 2 J DVD AIR Air Bud J DVD AIR Air buddies J DVD ALA Aladdin J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALICE Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALL All dogs go to heaven J DVD ALL All about fall J DVD ALV Alvin and the chipmunks. -

July 2009 AETN Magazine

Contents AETN MAGAZINE Staff KUAR, KLRE, KUAF Editor in Chief ow that all AETN Allen Weatherly N On the Cover.........2 AETN would like to give a special transmitters are thanks to the above long-time Editors broadcasting in digital, Concert underwriters of American Masters. Mona Dixon Kathy Atkinson you can enjoy additional Reconnect............3 On The Cover.... streams of programming Editorial & Creative Directors From the AMERICAN MASTERS –Garrison Keillor: The Sara Willis on AETN Kids/Create and AETN Scholar! A lot of Director................4 Man on the Radio in the Red Shoes Elizabeth duBignon you have been asking what these channels are Wednesday, July 1, 7 p.m. (Repeats 7/4, 5:30 p.m.) Editorial Panel and how to get them. Simply put, a digital Outreach..............5 Rowena Parr, Pam Wilson, Dan Koops Lake Wobegon – where the women are strong, Tiffany Verkler signal can be broken up into sub-channels, and AETNFoundation the men are good looking and all the children are we have named our sub-channels Kids/Create Ambassadors above average – has become America’s collective Copy Editors Darbi Blencowe, Catherine Mays, and Scholar. The channels are already available Circle...................6 hometown, visited weekly for the past 40 years on Karen Cooper, Pat Pearce to watch over the air using an antenna with a fictional radio program that creates bona fide Production............7 AETN Offices a converter box or digital television. The main nostalgia. With his “Prairie Home Companion,” 350 S. Donaghey Ave. - Conway, AR - channel number will depend on which AETN channel Highlights.............8 Keillor became our national philosopher, filling 72034 800/662-2386 you watch, but the sub-channel will always be the PBS Ongoing the empty shoes of Will Rogers and Mark Twain, [email protected] - www.aetn.org same. -

Sesame Street

Sesame Street The first TV show to achieve early-childhood learning gains, launched in the United States in the late 1960s, is now viewed by more than 156 million children around the world. In the mid-1960s, a new wave of research revealed the depths of unmet This case study is part of a series that accompanies The Bridgespan Group article educational needs of impoverished “Audacious Philanthropy: Lessons from 15 World-Changing Initiatives” (Harvard preschool-age children and the high Business Review, Sept/Oct 2017). See below for 15 stories of social movements costs of addressing these needs via that defied the odds and learn how traditional classroom-based programs philanthropy played a role in achieving their life-changing results. like Head Start. Against this backdrop, • The Anti-Apartheid Movement the concept of using television as • Aravind Eye Hospital a vehicle to improve early childhood • Car Seats • CPR Training education at scale came up at a • The Fair Food Program 1966 dinner conversation between • Hospice and Palliative Care documentarian Joan Ganz Cooney • Marriage Equality • Motorcycle Helmets in Vietnam and Carnegie Corporation of New York • The National School Lunch Program Vice President Lloyd Morrisett. • 911 Emergency Services • Oral Rehydration Together, they developed the concept and launched • Polio Eradication a new program they called Sesame Street, and by 1993, 77 percent of all preschoolers in the • Public Libraries United States watched the show at least once a • Sesame Street week, including 88 percent of those from low- • Tobacco Control income families, with significant positive effects. Among other outcomes, a recent study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that children who watched were more likely to be kindergarten-ready and an estimated 30 to 50 percent less likely to fall behind grade level, with the greatest impacts on the most disadvantaged children. -

Pub Type Edrs Price Descriptors

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 233 705 IR 010 796' TITLE Children and Television. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications, Consumer Protection, and Finance of the Committee on Energy and ComMerce, House of Representatives, Ninety-Eighth Congress, First Session. Serial No. 98-3. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Eneygy and Commerce. PUB DATE- 16 Mar 83 NOTE 221p.; Photographs and small print of some pages may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE --Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09'Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cable Television; *Childrens Television; Commercial Television; Educational Television; Federal Legislation; Hearings; Mass Media Effects; *ProgrAming (Broadcast); *Public Television; * Television Research; *Television Viewing; Violence IDENTIFIERS Congress 98th ABSTRACT Held, during National Children and Television Week, this hearing addressed the general topic of television and its impact on children, including specific ,children's televisionprojects and ideas for improving :children's television. Statements and testimony (when given) are presented for the following individuals and organizations: (1) John Blessington,-vice president, personnel, CBS/Broadcast Group; (2) LeVar Burton, host, Reading Rainbow; (3) Peggy Charren, president, National Action for Children's Television; (4) Bruce Christensen, president, National Association of;Public Television Stations; (5) Edward 0. Fritts, president, National Association of Broadcasters; (6) Honorable John A. Heinz, United States Senator, Pennsylvania; (7) Robert Keeshan, Captain Kangaroo; \(8) Keith W. Mielke, associate vice president for research, Children's Television Workshop; (9) Henry M. Rivera, Commissioner, , Federal Communications Commission; (10) Sharon Robinson, director, instruction and Professional Development, National Education Association; (11) Squire D. Rushnell, vice president, Long Range Planning and Children's Television, ABC; (12) John A. -

West Islip Public Library

CHILDREN'S TITLES (including Parent Collection) - as of January 1, 2013 NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a firefighter (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a zoo (CC) G African cats (SDH) PG Agent Cody Banks 2: destination London (CC) PG Alabama moon G Aladdin (2v) (CC) G Aladdin: the Return of Jafar (CC) PG Alex Rider: Operation stormbreaker (CC) NRA Alexander Graham Bell PG Alice in wonderland (2010-Johnny Depp) (SDH) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (CC) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (SDH) (2010 release) PG Aliens in the attic (SDH) NRA All aboard America (CC) NRA All about airplanes and flying machines NRA All about big red fire engines/All about construction NRA All about dinosaurs (CC) NRA All about dinosaurs/All about horses NRA All about earthquakes (CC) NRA All about electricity (CC) NRA All about endangered & extinct animals (CC) NRA All about fish (CC) NRA All about -

The Influence of Early Media Exposure on Children's Development And

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses July 2017 THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING Katherine Hanson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Developmental Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Hanson, Katherine, "THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1011. https://doi.org/10.7275/9875377.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1011 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING A Dissertation Presented by KATHERINE G. HANSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 Psychology © Copyright by Katherine G. Hanson 2017 All Rights Reserved THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING A Dissertation Presented by KATHERINE G. HANSON Approved as to style and content by: ________________________________________ Daniel R. Anderson, Chair ________________________________________ David Arnold, Member ________________________________________ Jennifer M. McDermott, Member ________________________________________ Erica Scharrer, Member ________________________________________ Hal Grotevant, Department Head Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Jennifer Kotler and Rosemarie Truglio for their support during my time at Sesame Workshop and their encouragement to go to graduate school.