Understanding Morriston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Programme 2021 to 2022 How We Are Investing to Reduce the Risk of Flooding and Coastal Erosion to Communities

PUBLICATION Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Programme 2021 to 2022 How we are investing to reduce the risk of flooding and coastal erosion to communities. First published: 19 March 2021 Last updated: 19 March 2021 This document was downloaded from GOV.WALES and may not be the latest version. Go to https://gov.wales/flood-and-coastal-erosion-risk-management-programme-2021-2022-html for the latest version. Get information on copyright. Contents Overview Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Coastal Risk Management Programme Small Scale Schemes Natural Flood Management Overview Each financial year the Welsh Government invites Risk Management Authorities (RMAs) to bid for funding to deliver a programme of capital works to reduce the risk of flooding and coastal erosion to communities across Wales. Capital projects undertaken by RMAs (Local Authorities, Natural Resources Wales and Water Companies) help to deliver the aims of the National Strategy for Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management in Wales. Applications for funding submitted by RMAs are considered by the Flood and Coastal Risk Programme Board before being agreed by the Minister for Environment, Energy and Rural Affairs. These are prioritised towards the communities most at risk of flooding, in accordance with our National Strategy, technical guidance and grant memorandum. The Welsh Government does not accept bids directly from individuals or organisations who are not a RMA. You should approach your Local Authority or Natural Resources Wales if you This document was downloaded from GOV.WALES and may not be the latest version. Go to https://gov.wales/flood-and-coastal-erosion-risk-management-programme-2021-2022-html for the latest version. -

Llansamlet Area 1 Location: Land at Heron Way, Swansea Enterprise

APPENDIX B ITEM APPLICATION NO. 2014/0765 WARD: Llansamlet Area 1 Location: Land at Heron Way, Swansea Enterprise Park, Swansea Proposal: Construction of retail unit (Class A1) (amendment to planning permission 2013/1616 granted for the construction of four retail units (Class A3) with associated works) Applicant: Actoris Commercial Limited BACKGROUND INFORMATION POLICIES Policy Policy Description Policy AS2 Accessibility - Criteria for assessing design and layout of new development. (City & County of Swansea Unitary Development Plan 2008) Policy AS6 Provision of car parking in accordance with adopted standards. (City & County of Swansea Unitary Development Plan 2008) Policy EV1 New development shall accord with a defined set of criteria of good design. (City & County of Swansea Unitary Development Plan 2008). Policy EV2 The siting of new development shall give preference to the use of previously developed land and have regard to the physical character and topography of the site and its surroundings. (City & County of Swansea Unitary Development Plan 2008). Policy EV3 Proposals for new development and alterations to and change of use of existing buildings will be required to meet defined standards of access. (City & County of Swansea Unitary Development Plan 2008) Policy EV36 New development, where considered appropriate, within flood risk areas will only be permitted where developers can demonstrate to the satisfaction of the Council that its location is justified and the consequences associated with flooding are acceptable. (City & County of Swansea Unitary Development Plan 2008) Policy EC3 Improvement and enhancement of the established industrial and commercial areas will be encouraged where appropriate through building enhancement, environmental improvement, infrastructure works, development opportunities and targeted business support. -

961 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

961 bus time schedule & line map 961 Llansamlet - Swansea College via Winch Wen View In Website Mode The 961 bus line Llansamlet - Swansea College via Winch Wen has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Tycoch: 7:38 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 961 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 961 bus arriving. Direction: Tycoch 961 bus Time Schedule 59 stops Tycoch Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:38 AM Church Road, Llansamlet 141 Samlet Road, Swansea Tuesday 7:38 AM Lon-Las School, Gwernllwynchwyth Wednesday 7:38 AM Walters Road Roundabout, Gwernllwynchwyth Thursday 7:38 AM Friday 7:38 AM Walters Road, Felin Fran Walters Road, Llansamlet Community Saturday Not Operational Ynysallan Road, Heol-Las Heol Las, Heol-Las 961 bus Info Smiths Road, Birchgrove Direction: Tycoch Stops: 59 Heol Dulais, Heol-Las Trip Duration: 53 min Line Summary: Church Road, Llansamlet, Lon-Las Heol Dulais Corner, Birchgrove School, Gwernllwynchwyth, Walters Road Roundabout, Gwernllwynchwyth, Walters Road, Felin Heol Dulais, Birchgrove Community Fran, Ynysallan Road, Heol-Las, Heol Las, Heol-Las, School, Birchgrove Smiths Road, Birchgrove, Heol Dulais, Heol-Las, Heol Dulais Corner, Birchgrove, School, Birchgrove, Bridgend Inn, Birchgrove, Birchgrove Road, Bridgend Inn, Birchgrove Birchgrove, Birchgrove Stores, Birchgrove, Birchgrove Hill, Peniel Green, Peniel Green East, Birchgrove Road, Birchgrove Peniel Green, Library, Peniel Green, Llansamlet Railway Station, Peniel Green, Llansamlet -

Heritage Statement Land to the North of Felindre Road, Pencoed, CF35 5HU

The pricesHeritage below reflect Statement some of our tailored products which allows you, our client, to haveLand the piece to ofthe mind North about theof Felindreoverall cost Road,impact for Pencoed, your individual CF35 projects: 5HU For By GK Heritage Consultants Ltd April 2019 V4 (ed) October 2019. Heritage Statement: Land to the North of Felindre Road, Pencoed, CF35 5HU Heritage Statement Land to the North of Felindre Road, Pencoed, CF35 5HU GK Heritage Consultants Ltd Report 2019/121 April 2019 © GK Heritage Consultants Ltd 2018 3rd Floor, Old Stock Exchange, St Nicholas Street, Bristol, BS1 1TG www.gkheritage.co.uk Prepared on behalf of: Energion Date of compilation: April 2019 Compiled by: G Kendall MCIfA Local Authority: Bridgend County Borough Council Site central NGR: SS96908137: (296908, 181377) i Heritage Statement: Land to the North of Felindre Road, Pencoed, CF35 5HU TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Project and Planning Background ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Site Description ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Proposed Development ........................................................................................................................................ -

Report on the Examination Into the Swansea Local Development Plan 2010 – 2025

Adroddiad i Gyngor Report to Swansea Abertawe Council gan: by: Rebecca Phillips BA (Hons) MSc DipM Rebecca Phillips BA (Hons) MSc DipM MRTPI MCIM MRTPI MCIM Paul Selby BEng (Hons) MSc MRTPI Paul Selby BEng (Hons) MSc MRTPI Arolygyddion a benodir gan Weinidogion Inspectors appointed by the Welsh Cymru Ministers Dyddiad: 31/01/19 Date: 31/01/19 PLANNING AND COMPULSORY PURCHASE ACT 2004 (AS AMENDED) SECTION 64 REPORT ON THE EXAMINATION INTO THE SWANSEA LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2010 – 2025 Plan submitted for examination on 28 July 2017 Hearings held 6 February – 28 March 2018 and 10 – 11 September 2018 Cyf ffeil/File ref: 515477 Swansea Local Development Plan 2010-2025 – Inspectors’ Report Abbreviations used in this report AA Appropriate Assessment AONB Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty AQMA Air Quality Management Area CBEEMS Carmarthen Bay and Estuaries European Marine Site DAMs Development Advice Maps DCWW Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water FCA Flood Consequences Assessment HRA Habitats Regulations Assessment IDP Infrastructure Delivery Plan IMAC Inspectors’ Matters Arising Change LDP Local Development Plan LHMA Local Housing Market Assessment LPA Local Planning Authority LSA Local Search Area MAC Matters Arising Change MoU Memorandum of Understanding NRW Natural Resources Wales PPW Planning Policy Wales RSL Registered Social Landlord SA Sustainability Appraisal SCARC Swansea Central Area Retail Centre SCARF Swansea Central Area Regeneration Framework SDA Strategic Development Area SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment SHPZ Strategic Housing Policy -

Tree Planting on Man-Made Sites in Wales

IEE PLANTING ON MAN-MADE SITES mmmmm Forestry Commission ARCHIVE TREE PLANTING ON MAN-MADE SITES IN WALES by K.F. Broad Forestry Commission Introduction by J.W.L. Zehetmayr Senior Officer for Wales, Forestry Commission Forestry Commission 1979 FOREWORD This paper is the record of thirty years work on planting in Wales, carried out by the Forestry Commission outwith its main remit for growing timber. Most of the reclamation of derelict land or tips and much of the planting has been financed by Government Agencies or Local Authorities and much of the resulting plantation has been or will be incorporated into the Commission's Forests. The initiative for this paper came from a review for the Prince of Wales' Committee, the objective of which is to conserve and enhance the Welsh environment, both rural and urban. A general summary prepared by J.W.L. Zehetmayr (Senior Officer for Wales, Forestry Commission) served as the basis for a detailed study by K.F. Broad (Research and Development Division, Forestry Commission, in 1974-75, which forms the main text. It seems likely that the Forestry Commission will continue with such work for many years, particularly in South Wales, given the continued drive to clear dereliction and at the same time to step up opencast working. 2 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 5 Chapter 1. METHODS OF SURVEY 12 Chapter 2. OPENCAST COAL SITES 13 Origins and characteristics 13 Vegetation 14 Methods of establishment 14 Choice of species 15 Results of survey 17 Overall growth Relative growth variability of growth Recent experimentation 19 Conclusions 20 Chapter 3. -

View in Website Mode

31 bus time schedule & line map 31 Swansea - Morriston Cross View In Website Mode The 31 bus line (Swansea - Morriston Cross) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birchgrove: 7:30 AM - 10:50 PM (2) Morriston: 3:10 PM (3) Morriston Hospital: 7:00 AM - 7:05 PM (4) Swansea: 6:40 AM - 10:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 31 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 31 bus arriving. Direction: Birchgrove 31 bus Time Schedule 32 stops Birchgrove Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:50 PM - 10:50 PM Monday 7:30 AM - 10:50 PM Bus Station H, Swansea Garden Street, Swansea Tuesday 7:30 AM - 10:50 PM Sainsbury'S, St Thomas Wednesday 7:30 AM - 10:50 PM Quay Parade, Swansea Thursday 7:30 AM - 10:50 PM Ship Inn, St Thomas Friday 7:30 AM - 10:50 PM Kilvey Terrace, Grenfell Park Saturday 8:05 PM - 10:50 PM Pentreguinea Road, Swansea Maesteg Street, Grenfell Park Foxhole Road, Foxhole 31 bus Info Direction: Birchgrove Pentrechwyth Road, Pentre-Chwyth Stops: 32 Trip Duration: 33 min Gwyndy Stores, Pentre-Chwyth Line Summary: Bus Station H, Swansea, Sainsbury'S, St Thomas, Ship Inn, St Thomas, Kilvey Pen-Y-Garn, Hanover Square Terrace, Grenfell Park, Maesteg Street, Grenfell Park, B5444, Bonymaen Community Foxhole Road, Foxhole, Pentrechwyth Road, Pentre- Chwyth, Gwyndy Stores, Pentre-Chwyth, Pen-Y-Garn, Jersey Arms, Pentre-Chwyth Hanover Square, Jersey Arms, Pentre-Chwyth, Chip Shop, Bonymaen, Bonymaen Inn, Bonymaen, Clinic, Chip Shop, Bonymaen Bonymaen, Caernarfon Way, Bonymaen, Cefn Hengoed School, -

Neath 32 Swansea

First Swansea - Birchgrove - Morriston Hospital 31 via Bonymaen, Trallwn & Enterprise Park Swansea - Neath 32 via Bonymaen, Trallwn, Birchgrove & Skewen Swansea - Trallwn/Frederick Place 33 via Bonymaen MONDAY TO FRIDAY Ref.No.: 71R Service No 33 33 31 31 32 33 31 33 32 33 31 33 32 33 SD Swansea City Bus Station 0550 0635 .... 0730 0745 0800 0815 0830 0845 0900 0915 0930 0945 1000 Sainsbury's 0554 0639 .... 0734 0749 0804 0819 0834 0849 0904 0919 0934 0949 1004 St Thomas (Ship Inn) 0556 0641 .... 0736 0753 0806 0821 0836 0853 0906 0921 0936 0953 1006 Maesteg Street 0558 0643 .... 0739 0755 0810 0825 0840 0855 0910 0925 0940 0955 1010 Bonymaen Inn 0601 0647 0700B0746 0800 0815 0830 0845 0900 0915 0930 0945 1000 1015 Colwyn Avenue (Post Office) 0604 0650 0704 0748 0805 0820 0835 0850 0905 0920 0935 0950 1005 1020 Trallwn (Shops) 0609 0656 0710 0754 0811 0826 0841 0856 0911 0926 0941 0956 1011 1026 Trallwn Glan-y-Wern Road .... 0658 .... .... .... 0829 .... 0859 .... 0929 .... 0959 .... 1029 Frederick Place (Brynteg) .... 0702 .... .... .... 0834 .... 0904 .... 0934 .... 1004 .... 1034 Peniel Green 0611 .... 0713 0759 0816 .... 0844 .... 0916 .... 0944 .... 1016 .... Birchgrove (Ffordd-y-Mynydd) .... .... .... .... 0820 .... .... .... 0920 .... .... .... 1020 .... Birchgrove (Bridgend Inn) 0615 .... 0717 .... 0822 .... 0850 .... 0922 .... 0950 .... 1022 .... Birchgrove School .... .... .... 0806 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... Birchgrove (Heol Dulais) 0616 .... 0719 .... 0824 .... 0852 .... 0924 .... 0952 .... 1024 ... -

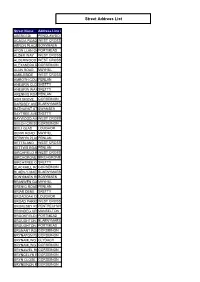

Street Address List

Street Address List Street Name Address Line 2 ABERCEDI PENCLAWDD ACACIA ROAD WEST CROSS AERON PLACEBONYMAEN AFON LLAN GARDENSPORTMEAD ALDER WAY WEST CROSS ALDERWOOD ROADWEST CROSS ALEXANDRA ROADGORSEINON ALUN ROAD MAYHILL AMBLESIDE WEST CROSS AMROTH COURTPENLAN ANEURIN CLOSESKETTY ANEURIN WAYSKETTY ARENNIG ROADPENLAN ASH GROVE GORSEINON BARDSEY AVENUEBLAENYMAES BATHURST STREETSWANSEA BAYTREE AVENUESKETTY BAYWOOD AVENUEWEST CROSS BEECH CRESCENTGORSEINON BEILI GLAS LOUGHOR BERW ROAD MAYHILL BERWYN PLACEPENLAN BETTSLAND WEST CROSS BETTWS ROADPENLAN BIRCHFIELD ROADWEST CROSS BIRCHGROVE ROADBIRCHGROVE BIRCHTREE CLOSESKETTY BLACKHILL ROADGORSEINON BLAEN-Y-MAESBLAENYMAES DRIVE BONYMAEN ROADBONYMAEN BRANWEN GARDENSMAYHILL BRENIG ROAD PENLAN BRIAR DENE SKETTY BROADOAK COURTLOUGHOR BROAD PARKSWEST CROSS BROKESBY ROADPENTRECHWYTH BRONDEG CRESCENTMANSELTON BROOKFIELD PLACEPORTMEAD BROUGHTON AVENUEBLAENYMAES BROUGHTON AVENUEPORTMEAD BRUNANT ROADGORSEINON BRYNAFON ROADGORSEINON BRYNAMLWG CLYDACH BRYNAMLWG ROADGORSEINON BRYNAWEL ROADGORSEINON BRYNCELYN ROADGORSEINON BRYN CLOSE GORSEINON BRYNEINON ROADGORSEINON BRYNEITHIN GOWERTON BRYNEITHIN ROADGORSEINON BRYNFFYNNONGORSEINON ROAD BRYNGOLAU GORSEINON BRYNGWASTADGORSEINON ROAD BRYNHYFRYD ROADGORSEINON BRYNIAGO ROADPONTARDULAIS BRYNLLWCHWRLOUGHOR ROAD BRYNMELIN STREETSWANSEA BRYN RHOSOGLOUGHOR BRYNTEG CLYDACH BRYNTEG ROADGORSEINON BRYNTIRION ROADPONTLLIW BRYN VERNEL LOUGHOR BRYNYMOR THREE CROSSES BUCKINGHAM ROADBONYMAEN BURRY GREENLLANGENNITH BWLCHYGWINFELINDRE BYNG STREET LANDORE CABAN ISAAC ROADPENCLAWDD -

(Beaufort Bridge, Morriston, Swansea) Order 2013 En

HIGHWAYS, WALES 2013 NO. 20 TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 THE STOPPING UP OF HIGHWAYS (BEAUFORT BRIDGE, MORRISTON, SWANSEA) ORDER 2013 Made 26 July2013 Coming into force 1 August2013 The Welsh Ministers make this Order in exercise of their powers under section 247 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990(1) (hereinafter referred to as "the Act of 1990") and of all other enabling powers(2). 1. In this Order:- “the Council” (“y Cyngor”) means the County Council of the City and County of Swansea; “the deposited plan” (“y plan a adneuwyd”) means the plan entitled “The Stopping Up Of Highways (Beaufort Bridge, Morriston, Swansea) Order 2013” which accompanies this Order; “the developer” (“y datblygwr”) means the person carrying out the development for which the planning permission referred to below has been given. 2. Subject to the provisions of articles 3, 4, 5 and 6 of this Order, the Welsh Ministers authorise the stopping up of the area of highway described in Schedule 1 to this Order and shown by zebra hatching on the deposited plan, being satisfied that the stopping up is necessary to enable development to be carried out as described in Schedule 3 to this Order, in accordance with planning permission granted by the Council under Part III of the Act of 1990, on 24 January 2013 under reference 2012/1376. 3. There shall be created, to the reasonable satisfaction of the Council, the new area of highway described in Schedule 2 to this Order and shown by stipple marking on the deposited plan, which is to be highway which, for the purposes of the Highways Act 1980(3) is highway maintainable at the public expense and the Council is to be the highway authority for it. -

Clear Streams Swansea (2013/14) Project Report and Evaluation

Clear Streams Swansea (2013/14) Project Report and Evaluation Contents Executive Summary 1. Introductory Information 1.1 Purpose and Scope of this Report 4 1.2 The Clear Streams Concept 4 1.3 Dŵr Cymru WFD Project Funding 5 1.4 Project Funding Applications 5 2. Project Report 2.1 Project Aims 6 2.2 Organisation and Resources 7 2.3 Project Activities 10 2.3.1 Engaging Local Businesses 10 2.3.2 Engaging Householders and Communities 12 2.3.3 Engaging Partners 20 2.4 Publicity and Marketing 21 3. Project Evaluation 3.1 Online Survey 23 3.2 Delivery of Outcomes and Objectives 25 3.3 Project Governance 27 3.4 Lessons Learnt and Recommendations 28 This report has been prepared by PMDevelopments Executive Summary The Clear Streams Swansea project was an eighteen-month collaboration between Swansea Environmental Forum, the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales and Natural Resources Wales. The project, funded by the Dŵr Cymru WFD Project Funding scheme, aimed to raise awareness of the water environment and improve water quality in the Swansea area. The project was part of, and built upon, a wider initiative developed by Environment Agency Wales, working in partnership with others to employ a holistic approach to managing water quality. Two new officer posts were created to deliver the project and these were supported by a steering group comprising representatives of the three partner organisations. The Dŵr Cymru WFD Project Funding scheme provided £100,000 to the project with an additional £30,000 contributed by Environment Agency Wales (replaced by Natural Resources Wales). -

Swansea Region

ASoloeErlcrv lElrtsnpul rol uollElcossv splou^au lned soq6nH uaqdels D -ir s t_ ?a ii I,. II I 1' a : a rii rBL n -. i ! i I ET .t) ? -+ I t ) I I I (, J*i I 0r0EuuEsrr eqt lo NOOTOHFti'c T$'rr!'I.snGME oqt ol ap!n9 v This booklel is published by the Associalion lor trial archaeology ol south-wesl and mid-Wales. lndustrial Archaeology in association with lhe lnlormation on lhese can be oblained lrom the Royal Commission on Ancient and Hislorical address given below. Detailed surveys, notes Monuments in Wales and the South Wesl Wales and illustrations ol these ieatures are either lndustrial Archaeology Sociely. lt was prepared housed in the Commission s pre-publication lor the annual conference of the AIA, held in records or in lhe National Monuments Record Swansea in 1988. lor Wales. The laller is a major archive lhat can be consulted, lree ol charge, during normal The AIA was established in 1973 lo promote working hours at the headquaners of the Royal lhe study ol industrial archaeology and encour- Commission on Ancaenl and Historical Monu- age improved slandards ol recording, re- ments in Wales. Edleston House, Oueen's search. conservalion and publication. lt aims lo Road, Aberyslwyth SY23 2HP; (a 0970- suppon individuals and groups involved in the 624381. study and recording ol past induslrial aclivily and the preservation ol industrial monuments; The SWWIAS was lormed an 1972 to sludy and to represent the interests of industrial archaeo' record lhe industraal hastory ol the western parl logy at a national leveli lo hold conlerences and ol lhe south Wales coaltield.