Translation of Address Terms in Hongloumeng Through Relevance Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: a Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: A Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in East Asian Studies April 2014 ©2014 Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Acknowledgements First of all, I thank Professor Ellen Widmer not only for her guidance and encouragement throughout this thesis process, but also for her support throughout my time here at Wellesley. Without her endless patience this study would have not been possible and I am forever grateful to be one of her advisees. I would also like to thank the Wellesley College East Asian Studies Department for giving me the opportunity to take on such a project and for challenging me to expand my horizons each and every day Sincerest thanks to my sisters away from home, Amy, Irene, Cristina, and Beatriz, for the many late night snacks, funny notes, and general reassurance during hard times. I would also like to thank Joe for never losing faith in my abilities and helping me stay motivated. Finally, many thanks to my family and friends back home. Your continued support through all of my endeavors and your ability to endure the seemingly endless thesis rambles has been invaluable to this experience. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: THE PAIRING OF WOOD AND GOLD Lin Daiyu ................................................................................................. -

Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou Meng

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses) Department of History March 2007 Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng Carina Wells [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors Wells, Carina, "Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng" (2007). Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses). 6. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng Comments A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 University of Pennsylvania Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng A senior thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History by Carina L. Wells Philadelphia, PA March 23, 2003 Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei Honors Director: Julia Rudolph Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………...i Explanatory Note…………………………………………………………………………iv Dynasties and Periods……………………………………………………………………..v Selected Reign -

The Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Tale of Genji and a Dream of Red Mansions

Volume 5, No. 2-3 24 The Cross-cultural Comparison of The Tale of Genji and A Dream of Red Mansions Mengmeng ZHOU Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China; Email: [email protected] Abstract: The Tale of Genji, and A Dream of Red Mansions are the classic work of oriental literature. The protagonists Murasaki-no-ue and Daiyu, as the representatives of eastern ideal female images, reflect the similarities and differences between Japanese culture and Chinese culture. It is worthwhile to elaborate and analyze from cross-cultural perspective in four aspects: a) the background of composition; b)the psychological character; c) the cultural aesthetic orientation; and d)value orientation. Key Words: Murasaki-no-ue; Daiyu; cross-cultural study 1. THE BACKGROUND OF COMPOSITION The Tale of Genji, is considered to be finished in its present form between about 1000 and 1008 in Heian-era of Japan. The exact time of final copy is still on doubt. The author Murasaki Shikibu was born in a family of minor nobility and a member the northern branch of the Fujiwara clan. It is argued that her given name might have been Fujiwara Takako. She had been a maid of honor in imperial court. As a custom in imperial court, the maid of honor was given an honorific title by her father or her brother‘s position. ―Shikibu‖ refers to her elder brother‘s position in the Bureau of Ceremony (shikibu-shō).―Murasaki‖ is her nickname, which is called by the readers, after the character Murasaki-no-ue in The Tale of Genji. -

Woodcut Illustrated Books in Late Imperial China: Visualisations of a Dream of Read Mansions

Woodcut Illustrated Books in Late Imperial China: Visualisations of A Dream of Read Mansions Kristína Janotová Lately, studies on the relationship between images and texts have increased exponentially. The reputation of book illustration as a minor art is rapidly being dissipated and images are being accepted as valuable material objects and epistemological cultural artefacts. Their research is extremely important for the evaluation of both images and texts. Therefore, the interaction between visual and textual images, their reception and interpretation have become topics in their own right. The connection between the art of the book and the method used for its printing has been close in all cultures in the world. The movable metal type in Europe, invented by the German Johannes Gutenberg around 1450, was cheap enough to replace woodblock printing for the reproduction of European texts. Book illustrations, however, were still produced through the woodblock printing method, which remained a major way to produce images in early modern European illustrated works. 1 While acknowledging the generally accepted originality of Gutenberg’s invention,2 the appearance of Chinese book illustra- tions, printed textiles and playing cards must have had a great impact on it. Since Chinese culture was regarded as a superior culture, Europeans borrowed some of its elements, at least until the end of the eighteenth century. For example, at the end of the 17th century, Louis XIV (1638–1715) and the Kangxi 康熙 Emperor 1 Donald F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 78. 2 Bi Sheng 畢 昇 (990–1051), an unsuccessful scholar hired by a printing house in Hangzhou, developed a printing method with movable type of hardened clay as early as the Northern Song dynasty. -

John Zijiang Ding

MYSTICAL SYMBOLISM AND DIALETHEIST COGNITIVISM: THE TRANSFORMATION OF TRUTH- FALSEHOOD (ZHEN-JIA) John Zijiang Ding Abstract: One of the central philosophical issues is the problem of Truth-Falsehood (Zhen-Jia) in A Dream of Red Mansions. We may find three positions in this book: The first is “Truth” (Zhen) which also means “Being,” “Reality,” “Existence,” “Physical and Materialistic Substance,” and “Actual Social affairs”; the second is “Falsehood” (Jia) which means “Non-Being,” “Emptiness,” “Nothingness,” “Nihility,” “Illusory Fiction,” and “Spiritual and Mental Activities;” and the third is “Truth-Falsehood” (Zhen-Jia). The third can be considered “Transformation of Truth and Falsehood,” which has the following four attributes in this book: 1) Unification of truth and falsehood; 2) Interrelation of truth and falsehood; 3) Interaction of truth and falsehood; 4) Inter-substitution of truth and falsehood. The transformation of Truth-Falsehood (Zhen-Jia) in this book can be considered a sort of spiritual transformation which is recognized within the context of an individual self-consciousness, or an individual's meaning system, especially in relation to the concepts of the sacred or ultimate concern. In this article, the author will discuss this theme by explaining and examining the relationship and transformation of “Truth” and “falsehood” through the following three perspectives: traditional Chinese glyphomancy, dialetheism and fatalism. A Dream of Red Mansions――HONG LOU MENG 紅樓夢 is one of the four greatest Chinese classic novels. 1 It may be proper to justify that to understand China, one must read this great work because of its tremendous influence on Chinese literary history. Importantly, the study of this novel has become as popular and prolific as the works of Shakespeare or Goethe. -

The Fall of a Family: Tracing the Aristotelian Model of Catastrophe In

1 The Fall of a Family Tracing the Aristotelian Model of Catastrophe in Dream of the Red Chamber and Buddenbrooks Cecily Cai In the Poetics, Aristotle claims that tragedy is a mimesis of an elevated action that evokes pity and fear.1 The core of tragedy is the plot and, according to Aristotle, the best kind contains peripeteia or catastrophe that is the reversal of fortune from good to bad. Guided by this Aristotelian model, I attempt to read two great novels that epitomize the catastrophe within a family. Although originating from two different cultures and time periods, both Cao Xueqin’s Hong Lou Meng (Dream of the Red Chamber, hereafter HLM) and Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks stand out in their unified theme of Verfall (decline). Each novel bears its own traces of an Aristotelian tragedy and unfolds the catastrophe by way of elaborate foreshadowing implanted throughout the plot. Neither HLM nor Buddenbrooks strictly follows the structure of a tragedy in Aristotle’s time, yet both works are inspired by the spirit of tragedy in Aristotle’s Poetics and bear similar traces of the Aristotelian model in portraying the fall of a family. Following the framework illustrated by Aristotle,2 both HLM and Buddenbrooks are constructed upon a complex plot with a reversal in the course of the transformation that is the fall of the family. 1 “Tragedy, then, is a mimesis [mīmēsis] of an action [praxis] that is serious [spoudaiā], complete [teleiā], and having magnitude [megethos]; with language [logos] embellished individually in each of its forms [eidos plural] and in each of its parts [morion plural]. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 368 3rd International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2019) Discussion on the Influence of "A Dream of Red Mansions" on Zhang Ling's "The Affair of Flowers" Ting Ye Jinan University Guangzhou, China Abstract—The creation of the famous Chinese writer Zhang influenced by "A Dream of Red Mansions", which shows Ling is deeply influenced by the Chinese classic novel "A that culture has the nature of return in the form of Dream of Red Mansions". Zhang Ling's novel "The Affair of renaissance. Flowers" and Cao Xueqin's "A Dream of Red Mansions" have many aspects of intertextualities. "The Affair of Flowers" The two novelists Zhang Ling and Cao Xueqin are very follows the image of jade and flower in "A Dream of Red similar in their breath. In fact, the reading and research of Mansions". The beauty is like a flower, and the love is like jade Zhang Ling's "The Affair of Flowers" has evoked readers' makes "The Affair of Flowers" become a poetic novel. The interest and memory of the collection of Chinese classical corresponding arrangement of the two female main characters literature in "A Dream of Red Mansions". One of the in "The Affair of Flowers", Hua Yuyue and Hua Yunyun, Xue important revelations that can be gained from the reading of Baochai and Lin Daiyu, is especially evident in the efforts of "The Affair of Flowers" is to learn to use literature and life in writer Zhang Ling to create two equally wonderful female a holistic way. -

Toward a Maoist Dream of the Red Chamber: Or, How Baoyu and Daiyu Became Rebels Against Feudalism

Journal of chinese humanities 3 (���7) �77-�0� brill.com/joch Toward a Maoist Dream of the Red Chamber: Or, How Baoyu and Daiyu Became Rebels Against Feudalism Johannes Kaminski Postdoctoral Researcher, Academia Sinica, Taiwan [email protected] Abstract Mao Zedong’s views on literature were enigmatic: although he coerced writers into “learning the language of the masses,” he made no secret of his own enthusiasm for Dream of the Red Chamber, a novel written during the Qing dynasty. In 1954 this para- dox appeared to be resolved when Li Xifan and Lan Ling presented an interpretation that saw the tragic love story as a manifestation of class struggle. Ever since, the conception of Baoyu and Daiyu as class warriors has become a powerful and unques- tioned cliché of Chinese literary criticism. Endowing aristocratic protagonists with revolutionary grandeur, however, violates a basic principle of Marxist orthodoxy. This article examines the reasons behind this position: on the one hand, Mao’s support for Li and Lan’s approach acts as a reminder of his early journalistic agitation against arranged marriage and the social ills it engenders. On the other hand, it offers evidence of Mao’s increasingly ambiguous conception of class. Keywords class struggle – Dream of the Red Chamber – Hong Lou Meng – Mao Zedong – On Contradiction literature * I am grateful to the Academia Sinica in Taipei, in particular to the Department of Chinese Literature and Philosophy. Dr. Peng Hsiao-yen’s intellectual and moral support facilitated the research work that went -

A Tutorial on Libra: R Package for the Linearized Bregman Algorithm in High Dimensional Statistics

Chapter 1 A Tutorial on Libra: R package for the Linearized Bregman Algorithm in High Dimensional Statistics Jiechao Xiong, Feng Ruan, and Yuan Yao Abstract The R package, Libra, stands for the LInearized BRegman Algo- rithm in high dimensional statistics. The Linearized Bregman Algorithm is a simple iterative procedure to generate sparse regularization paths of model estimation, which are firstly discovered in applied mathematics for image restoration and particularly suitable for parallel implementation in large scale problems. The limit of such an algorithm is a sparsity-restricted gradient de- scent flow, called the Inverse Scale Space, evolving along a parsimonious path of sparse models from the null model to overfitting ones. In sparse linear regression, the dynamics with early stopping regularization can prov- ably meet the unbiased Oracle estimator under nearly the same condition as LASSO, while the latter is biased. Despite their successful applications, statistical consistency theory of such dynamical algorithms remains largely open except for some recent progress on linear regression. In this tutorial, algorithmic implementations in the package are discussed for several widely used sparse models in statistics, including linear regression, logistic regres- sion, and several graphical models (Gaussian, Ising, and Potts). Besides the simulation examples, various application cases are demonstrated, with real world datasets from diabetes, publications of COPSS award winners, as well as social networks of two Chinese classic novels, -

A Mysterious Woman in a Dream of Red Mansions: Qin Keqing

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 12, No. 2, 2016, pp. 40-43 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/8179 www.cscanada.org A Mysterious Woman in A Dream of Red Mansions: Qin Keqing GENG Chunling[a],* [a]Foreign Languages Departement, Inner Mongolia University for the Wangs and Xues described in the novel were typical Nationalities, Tongliao, China. political interconnected families of feudal society. Such Corresponding author. families were linked to the royal court and the local Received 30 October 2015; accepted 24 December 2015 officials, forming a network of control with the feudal Published online 26 February 2016 autocratic state power as its centre. Revolving around a tragic love between Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu with Xue Abstract Baochai, A Dream of Red Mansions mainly charts the Written in the mid-eighteenth century during the reign course of prosperity and decline of an aristocratic family of Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty, A Dream of — the Jias. Taking as its main theme the tragic love Red Mansions is regarded as one of the greatest Chinese between a couple of young aristocrats, Jia Baoyu and Lin classical novels. It has been popular throughout the last Daiyu, the novel describes the decline of the social milieu two hundred years and more. The whole work through of this well-known feudal aristocratic household. which is full of mysteries not only about the book, but A Dream of Red Mansions is a microcosm of the also about the author. Among many characters in A Dream world of its time and provides a panorama of lives of of Red Mansions, Qin Keqing is the most mysterious. -

Searchable PDF Format

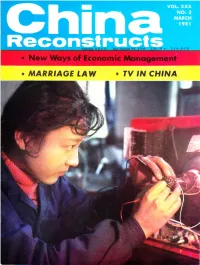

c t8 &.!,s {: ...{ Give the People Some Sweetness (woodcut, 1979) t\g PUBLTSHED MONTHLy GERMAN, cHlNEsE BY THE cHINA.tN-.ENgll_S.t-+-IEEryCfl, wrlrAne rnsfrrure 5_t4l,ilSE.ARABIC, tsoolc -txriiio'-[r'nG,'-afnr-Rttiiii.r] PORTUGUEsE AND vot. xxx No. 3 MARCH 1981 Articles of the Month CONTENTS Economy Reforming Economic Monogement Beforming Economic Managemenl 4 Chino's economy, Vast Changes in Naniing port 24 omidst reolistit od- justment torgets A Day in a Mountain Village 54 ol . ond priorities, is olso Questions of Moruioge the scene of initiol re- Why New Marriage Law Was Necessary lorms in its monoge- 17 ment Why they ore Finding a Wife,i Husband in ghanghai 21 needed, benelits re- Questions ond Answers reoled, new contro- dictions enGountered ls China 'Going Backward'? 8 - discus3ed by on Medio economist Poge ,l Entering the Television Age 11 China's Voice Abroad 52 Everyone Equo! Before the Low Low I Deportment of Beijirng Univer' Everyone Equal Before Membe the Law 28 sity ons the procedure, principles, legol Culture issues i of Jiong Qing ond other cul' prits conce for the luture. Pqge 28 Determined Philatelist Shen Zenghua 3l - Gu Yuan's Woodcuts and Watercolors JJ Yangzhou Papercuts and Zhang yongshou 46 Chino Enters Television Dai Ailian Fifty Years a Dancer 49 - Age Songfest in Guangxi 61 Qrowing production of TV Sports sets, now owned by millions. 'Monkey'Boxing 42 Moin content ol progroms Across the Lond news, entertoinment, -issue-oiring, educotioiiol Go Fly a Kite 27 courses - ond odvertising. Purple Sand Teaware of Yixing 40 Poge lt . -

The Eye and the Mirror: Visual Subjectivity in Chinese and American Literary Representations

THE EYE AND THE MIRROR: VISUAL SUBJECTIVITY IN CHINESE AND AMERICAN LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS by Guozhong Duan APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Ming Dong Gu, Chair ___________________________________________ David F. Channell ___________________________________________ Peter K. J. Park ___________________________________________ Dennis Walsh Copyright 2017 Guozhong Duan All Rights Reserved THE EYE AND THE MIRROR: VISUAL SUBJECTIVITY IN CHINESE AND AMERICAN LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS by GUOZHONG DUAN, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES—STUDIES IN LITERATURE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincerest gratitude first goes to Professor Ming Dong Gu, my supervisor, for his years of instructions and inspirations. This dissertation would not have been possible without the help from his insights and expertise in comparative literary studies and intellectual thoughts. His courses have introduced me to the interdisciplinary field of psychoanalysis, visual culture, and literary criticism, and have enabled me to conduct literary studies with a broader horizon. In addition to his help in academic training, his earnest attitude towards scholarship and persistent devotion to intellectual investigation have been and will be encouraging me in my own study. Professor David F. Channell’s course on space, time, and culture has provided me with knowledge of the Western intellectual history that is of great importance to my current comparative study. Professor Peter K. J. Park guided me through my field exams, for which he spent many afternoons with me on face-to-face instructions. His course on historiography of the European Enlightenment is an eye-opening experience for me and has initiated my interest in the history of ideas.