What Have Spacetime, Shape and Symmetry to Do with Thermodynamics?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swimming in Spacetime: Motion by Cyclic Changes in Body Shape

RESEARCH ARTICLE tation of the two disks can be accomplished without external torques, for example, by fixing Swimming in Spacetime: Motion the distance between the centers by a rigid circu- lar arc and then contracting a tension wire sym- by Cyclic Changes in Body Shape metrically attached to the outer edge of the two caps. Nevertheless, their contributions to the zˆ Jack Wisdom component of the angular momentum are parallel and add to give a nonzero angular momentum. Cyclic changes in the shape of a quasi-rigid body on a curved manifold can lead Other components of the angular momentum are to net translation and/or rotation of the body. The amount of translation zero. The total angular momentum of the system depends on the intrinsic curvature of the manifold. Presuming spacetime is a is zero, so the angular momentum due to twisting curved manifold as portrayed by general relativity, translation in space can be must be balanced by the angular momentum of accomplished simply by cyclic changes in the shape of a body, without any the motion of the system around the sphere. external forces. A net rotation of the system can be ac- complished by taking the internal configura- The motion of a swimmer at low Reynolds of cyclic changes in their shape. Then, presum- tion of the system through a cycle. A cycle number is determined by the geometry of the ing spacetime is a curved manifold as portrayed may be accomplished by increasing by ⌬ sequence of shapes that the swimmer assumes by general relativity, I show that net translations while holding fixed, then increasing by (1). -

Art Concepts for Kids: SHAPE & FORM!

Art Concepts for Kids: SHAPE & FORM! Our online art class explores “shape” and “form” . Shapes are spaces that are created when a line reconnects with itself. Forms are three dimensional and they have length, width and depth. This sweet intro song teaches kids all about shape! Scratch Garden Value Song (all ages) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=coZfbTIzS5I Another great shape jam! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6hFTUk8XqEc Cookie Monster eats his shapes! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gfNalVIrdOw&list=PLWrCWNvzT_lpGOvVQCdt7CXL ggL9-xpZj&index=10&t=0s Now for the activities!! Click on the links in the descriptions below for the step by step details. Ages 2-4 Shape Match https://busytoddler.com/2017/01/giant-shape-match-activity/ Shapes are an easy art concept for the littles. Lots of their environment gives play and art opportunities to learn about shape. This Matching activity involves tracing the outside shape of blocks and having littles match the block to the outline. It can be enhanced by letting your little ones color the shapes emphasizing inside and outside the shape lines. Block Print Shapes https://thepinterestedparent.com/2017/08/paul-klee-inspired-block-printing/ Printing is a great technique for young kids to learn. The motion is like stamping so you teach little ones to press and pull rather than rub or paint. This project requires washable paint and paper and block that are not natural wood (which would stain) you want blocks that are painted or sealed. Kids can look at Paul Klee art for inspiration in stacking their shapes into buildings, or they can chose their own design Ages 4-6 Lois Ehlert Shape Animals http://www.momto2poshlildivas.com/2012/09/exploring-shapes-and-colors-with-color.html This great project allows kids to play with shapes to make animals in the style of the artist Lois Ehlert. -

Molecular Symmetry

Molecular Symmetry Symmetry helps us understand molecular structure, some chemical properties, and characteristics of physical properties (spectroscopy) – used with group theory to predict vibrational spectra for the identification of molecular shape, and as a tool for understanding electronic structure and bonding. Symmetrical : implies the species possesses a number of indistinguishable configurations. 1 Group Theory : mathematical treatment of symmetry. symmetry operation – an operation performed on an object which leaves it in a configuration that is indistinguishable from, and superimposable on, the original configuration. symmetry elements – the points, lines, or planes to which a symmetry operation is carried out. Element Operation Symbol Identity Identity E Symmetry plane Reflection in the plane σ Inversion center Inversion of a point x,y,z to -x,-y,-z i Proper axis Rotation by (360/n)° Cn 1. Rotation by (360/n)° Improper axis S 2. Reflection in plane perpendicular to rotation axis n Proper axes of rotation (C n) Rotation with respect to a line (axis of rotation). •Cn is a rotation of (360/n)°. •C2 = 180° rotation, C 3 = 120° rotation, C 4 = 90° rotation, C 5 = 72° rotation, C 6 = 60° rotation… •Each rotation brings you to an indistinguishable state from the original. However, rotation by 90° about the same axis does not give back the identical molecule. XeF 4 is square planar. Therefore H 2O does NOT possess It has four different C 2 axes. a C 4 symmetry axis. A C 4 axis out of the page is called the principle axis because it has the largest n . By convention, the principle axis is in the z-direction 2 3 Reflection through a planes of symmetry (mirror plane) If reflection of all parts of a molecule through a plane produced an indistinguishable configuration, the symmetry element is called a mirror plane or plane of symmetry . -

![Arxiv:1910.10745V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 23 Oct 2019 2.2 Symmetry-Protected Time Crystals](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4942/arxiv-1910-10745v1-cond-mat-str-el-23-oct-2019-2-2-symmetry-protected-time-crystals-304942.webp)

Arxiv:1910.10745V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 23 Oct 2019 2.2 Symmetry-Protected Time Crystals

A Brief History of Time Crystals Vedika Khemania,b,∗, Roderich Moessnerc, S. L. Sondhid aDepartment of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA bDepartment of Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, USA cMax-Planck-Institut f¨urPhysik komplexer Systeme, 01187 Dresden, Germany dDepartment of Physics, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08544, USA Abstract The idea of breaking time-translation symmetry has fascinated humanity at least since ancient proposals of the per- petuum mobile. Unlike the breaking of other symmetries, such as spatial translation in a crystal or spin rotation in a magnet, time translation symmetry breaking (TTSB) has been tantalisingly elusive. We review this history up to recent developments which have shown that discrete TTSB does takes place in periodically driven (Floquet) systems in the presence of many-body localization (MBL). Such Floquet time-crystals represent a new paradigm in quantum statistical mechanics — that of an intrinsically out-of-equilibrium many-body phase of matter with no equilibrium counterpart. We include a compendium of the necessary background on the statistical mechanics of phase structure in many- body systems, before specializing to a detailed discussion of the nature, and diagnostics, of TTSB. In particular, we provide precise definitions that formalize the notion of a time-crystal as a stable, macroscopic, conservative clock — explaining both the need for a many-body system in the infinite volume limit, and for a lack of net energy absorption or dissipation. Our discussion emphasizes that TTSB in a time-crystal is accompanied by the breaking of a spatial symmetry — so that time-crystals exhibit a novel form of spatiotemporal order. -

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space Martin Kilian Niloy J. Mitra Helmut Pottmann Vienna University of Technology Figure 1: Geodesic interpolation and extrapolation. The blue input poses of the elephant are geodesically interpolated in an as-isometric- as-possible fashion (shown in green), and the resulting path is geodesically continued (shown in purple) to naturally extend the sequence. No semantic information, segmentation, or knowledge of articulated components is used. Abstract space, line geometry interprets straight lines as points on a quadratic surface [Berger 1987], and the various types of sphere geometries We present a novel framework to treat shapes in the setting of Rie- model spheres as points in higher dimensional space [Cecil 1992]. mannian geometry. Shapes – triangular meshes or more generally Other examples concern kinematic spaces and Lie groups which straight line graphs in Euclidean space – are treated as points in are convenient for handling congruent shapes and motion design. a shape space. We introduce useful Riemannian metrics in this These examples show that it is often beneficial and insightful to space to aid the user in design and modeling tasks, especially to endow the set of objects under consideration with additional struc- explore the space of (approximately) isometric deformations of a ture and to work in more abstract spaces. We will show that many given shape. Much of the work relies on an efficient algorithm to geometry processing tasks can be solved by endowing the set of compute geodesics in shape spaces; to this end, we present a multi- closed orientable surfaces – called shapes henceforth – with a Rie- resolution framework to solve the interpolation problem – which mannian structure. -

TASI 2008 Lectures: Introduction to Supersymmetry And

TASI 2008 Lectures: Introduction to Supersymmetry and Supersymmetry Breaking Yuri Shirman Department of Physics and Astronomy University of California, Irvine, CA 92697. [email protected] Abstract These lectures, presented at TASI 08 school, provide an introduction to supersymmetry and supersymmetry breaking. We present basic formalism of supersymmetry, super- symmetric non-renormalization theorems, and summarize non-perturbative dynamics of supersymmetric QCD. We then turn to discussion of tree level, non-perturbative, and metastable supersymmetry breaking. We introduce Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model and discuss soft parameters in the Lagrangian. Finally we discuss several mech- anisms for communicating the supersymmetry breaking between the hidden and visible sectors. arXiv:0907.0039v1 [hep-ph] 1 Jul 2009 Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Motivation..................................... 2 1.2 Weylfermions................................... 4 1.3 Afirstlookatsupersymmetry . .. 5 2 Constructing supersymmetric Lagrangians 6 2.1 Wess-ZuminoModel ............................... 6 2.2 Superfieldformalism .............................. 8 2.3 VectorSuperfield ................................. 12 2.4 Supersymmetric U(1)gaugetheory ....................... 13 2.5 Non-abeliangaugetheory . .. 15 3 Non-renormalization theorems 16 3.1 R-symmetry.................................... 17 3.2 Superpotentialterms . .. .. .. 17 3.3 Gaugecouplingrenormalization . ..... 19 3.4 D-termrenormalization. ... 20 4 Non-perturbative dynamics in SUSY QCD 20 4.1 Affleck-Dine-Seiberg -

Observability and Symmetries of Linear Control Systems

S S symmetry Article Observability and Symmetries of Linear Control Systems Víctor Ayala 1,∗, Heriberto Román-Flores 1, María Torreblanca Todco 2 and Erika Zapana 2 1 Instituto de Alta Investigación, Universidad de Tarapacá, Casilla 7D, Arica 1000000, Chile; [email protected] 2 Departamento Académico de Matemáticas, Universidad, Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa, Calle Santa Catalina, Nro. 117, Arequipa 04000, Peru; [email protected] (M.T.T.); [email protected] (E.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 April 2020; Accepted: 6 May 2020; Published: 4 June 2020 Abstract: The goal of this article is to compare the observability properties of the class of linear control systems in two different manifolds: on the Euclidean space Rn and, in a more general setup, on a connected Lie group G. For that, we establish well-known results. The symmetries involved in this theory allow characterizing the observability property on Euclidean spaces and the local observability property on Lie groups. Keywords: observability; symmetries; Euclidean spaces; Lie groups 1. Introduction For general facts about control theory, we suggest the references, [1–5], and for general mathematical issues, the references [6–8]. In the context of this article, a general control system S can be modeled by the data S = (M, D, h, N). Here, M is the manifold of the space states, D is a family of differential equations on M, or if you wish, a family of vector fields on the manifold, h : M ! N is a differentiable observation map, and N is a manifold that contains all the known information that you can see of the system through h. -

Shape Synthesis Notes

SHAPE SYNTHESIS OF HIGH-PERFORMANCE MACHINE PARTS AND JOINTS By John M. Starkey Based on notes from Walter L. Starkey Written 1997 Updated Summer 2010 2 SHAPE SYNTHESIS OF HIGH-PERFORMANCE MACHINE PARTS AND JOINTS Much of the activity that takes place during the design process focuses on analysis of existing parts and existing machinery. There is very little attention focused on the synthesis of parts and joints and certainly there is very little information available in the literature addressing the shape synthesis of parts and joints. The purpose of this document is to provide guidelines for the shape synthesis of high-performance machine parts and of joints. Although these rules represent good design practice for all machinery, they especially apply to high performance machines, which require high strength-to-weight ratios, and machines for which manufacturing cost is not an overriding consideration. Examples will be given throughout this document to illustrate this. Two terms which will be used are part and joint. Part refers to individual components manufactured from a single block of raw material or a single molding. The main body of the part transfers loads between two or more joint areas on the part. A joint is a location on a machine at which two or more parts are fastened together. 1.0 General Synthesis Goals Two primary principles which govern the shape synthesis of a part assert that (1) the size and shape should be chosen to induce a uniform stress or load distribution pattern over as much of the body as possible, and (2) the weight or volume of material used should be a minimum, consistent with cost, manufacturing processes, and other constraints. -

Geometry and Art LACMA | | April 5, 2011 Evenings for Educators

Geometry and Art LACMA | Evenings for Educators | April 5, 2011 ALEXANDER CALDER (United States, 1898–1976) Hello Girls, 1964 Painted metal, mobile, overall: 275 x 288 in., Art Museum Council Fund (M.65.10) © Alexander Calder Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris EOMETRY IS EVERYWHERE. WE CAN TRAIN OURSELVES TO FIND THE GEOMETRY in everyday objects and in works of art. Look carefully at the image above and identify the different, lines, shapes, and forms of both GAlexander Calder’s sculpture and the architecture of LACMA’s built environ- ment. What is the proportion of the artwork to the buildings? What types of balance do you see? Following are images of artworks from LACMA’s collection. As you explore these works, look for the lines, seek the shapes, find the patterns, and exercise your problem-solving skills. Use or adapt the discussion questions to your students’ learning styles and abilities. 1 Language of the Visual Arts and Geometry __________________________________________________________________________________________________ LINE, SHAPE, FORM, PATTERN, SYMMETRY, SCALE, AND PROPORTION ARE THE BUILDING blocks of both art and math. Geometry offers the most obvious connection between the two disciplines. Both art and math involve drawing and the use of shapes and forms, as well as an understanding of spatial concepts, two and three dimensions, measurement, estimation, and pattern. Many of these concepts are evident in an artwork’s composition, how the artist uses the elements of art and applies the principles of design. Problem-solving skills such as visualization and spatial reasoning are also important for artists and professionals in math, science, and technology. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

The Symmetry Group of a Finite Frame

Technical Report 3 January 2010 The symmetry group of a finite frame Richard Vale and Shayne Waldron Department of Mathematics, Cornell University, 583 Malott Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853-4201, USA e–mail: [email protected] Department of Mathematics, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand e–mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT We define the symmetry group of a finite frame as a group of permutations on its index set. This group is closely related to the symmetry group of [VW05] for tight frames: they are isomorphic when the frame is tight and has distinct vectors. The symmetry group is the same for all similar frames, in particular for a frame, its dual and canonical tight frames. It can easily be calculated from the Gramian matrix of the canonical tight frame. Further, a frame and its complementary frame have the same symmetry group. We exploit this last property to construct and classify some classes of highly symmetric tight frames. Key Words: finite frame, geometrically uniform frame, Gramian matrix, harmonic frame, maximally symmetric frames partition frames, symmetry group, tight frame, AMS (MOS) Subject Classifications: primary 42C15, 58D19, secondary 42C40, 52B15, 0 1. Introduction Over the past decade there has been a rapid development of the theory and application of finite frames to areas as diverse as signal processing, quantum information theory and multivariate orthogonal polynomials, see, e.g., [KC08], [RBSC04] and [W091]. Key to these applications is the construction of frames with desirable properties. These often include being tight, and having a high degree of symmetry. Important examples are the harmonic or geometrically uniform frames, i.e., tight frames which are the orbit of a single vector under an abelian group of unitary transformations (see [BE03] and [HW06]). -

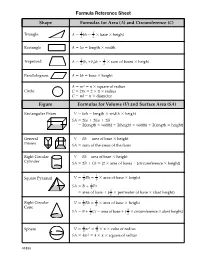

C) Shape Formulas for Volume (V) and Surface Area (SA

Formula Reference Sheet Shape Formulas for Area (A) and Circumference (C) Triangle ϭ 1 ϭ 1 ϫ ϫ A 2 bh 2 base height Rectangle A ϭ lw ϭ length ϫ width Trapezoid ϭ 1 + ϭ 1 ϫ ϫ A 2 (b1 b2)h 2 sum of bases height Parallelogram A ϭ bh ϭ base ϫ height A ϭ πr2 ϭ π ϫ square of radius Circle C ϭ 2πr ϭ 2 ϫ π ϫ radius C ϭ πd ϭ π ϫ diameter Figure Formulas for Volume (V) and Surface Area (SA) Rectangular Prism SV ϭ lwh ϭ length ϫ width ϫ height SA ϭ 2lw ϩ 2hw ϩ 2lh ϭ 2(length ϫ width) ϩ 2(height ϫ width) 2(length ϫ height) General SV ϭ Bh ϭ area of base ϫ height Prisms SA ϭ sum of the areas of the faces Right Circular SV ϭ Bh = area of base ϫ height Cylinder SA ϭ 2B ϩ Ch ϭ (2 ϫ area of base) ϩ (circumference ϫ height) ϭ 1 ϭ 1 ϫ ϫ Square Pyramid SV 3 Bh 3 area of base height ϭ ϩ 1 l SA B 2 P ϭ ϩ 1 ϫ ϫ area of base ( 2 perimeter of base slant height) Right Circular ϭ 1 ϭ 1 ϫ ϫ SV 3 Bh 3 area of base height Cone ϭ ϩ 1 l ϭ ϩ 1 ϫ ϫ SA B 2 C area of base ( 2 circumference slant height) ϭ 4 π 3 ϭ 4 ϫ π ϫ Sphere SV 3 r 3 cube of radius SA ϭ 4πr2 ϭ 4 ϫ π ϫ square of radius 41830 a41830_RefSheet_02MHS 1 8/29/01, 7:39 AM Equations of a Line Coordinate Geometry Formulas Standard Form: Let (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) be two points in the plane.