Thomas Lundén

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conferences, Technical Societies and Development – a History of Synergy Dr

Conferences, Technical Societies and Development – A History of Synergy Dr. Jacob Baal-Schem, IEEE SLM Tel-Aviv University, Israel Abstract — This paper is about IEEE Region 8 Conferences, Radio Engineers. Marriott became the first IRE president. To their raison d’être and their impact on the development of Electro- a large extent, they modeled their Institute on the AIEE, with technology in Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA), which membership grades, a journal, local sections, standards activ- constitute the geographical area of the Region. The claim is that technology conferences, held by ‘learned ities, and technical meetings, but there were other influences societies’ in different parts of Region 8, were necessary for the as well. They established their journal, the Proceedings of the technological development of the Region, in order to highlight IRE, along the lines of scientific journals, with papers directly and discuss the problems with which technology world is coping. submitted and peer review, which allowed for faster publication In order to set up these conferences, technology experts needed than AIEE’s policy that papers be presented at meetings first. technical societies, such as IEEE, to enable – among other activities – this facility. On the other hand, the holding of these They deliberately did not include ‘American’ in their name, to Conferences contributed to the technological development of the signify the transnational nature of radio. Therefore, as years Region and to the contact between scientists and engineers, for passed, new IRE sections were set up, first in the American the benefit of Humanity. continent and later in the Eastern Hemisphere, beginning with Thereby, IEEE Region 8 and the series of EUROCON, the Israel IRE Section, set up in 1954. -

EUREL NEWSLETTER, N° –

EUREL NEWSLETTER, n° 9 – avril / April 2009 Ceci est la neuvième lettre d'information du site Eurel (données sociologiques et juridiques sur la religion en Europe), publiée deux fois par an. / This is the ninth newsletter of the Eurel website (sociological and legal data on religions in Europe) which is published twice a year. Vous y trouverez des informations sur l'actualité du site, ainsi que, pour différents pays, les références des livres et articles récemment parus, les nouveaux sites internet, les derniers sondages, les prochains colloques consacrés à la sociologie et au droit des religions en Europe... The letter includes information concerning the recent changes in the Eurel website, as well as news concerning different countries of Europe: references of recent books or articles, new websites, latest surveys, and coming meetings concerning sociology and law of religions in Europe... 1. Actualité en droit et sociologie des religions / News in law and sociology of religion Allemagne / Germany Autriche / Austria Belgique / Belgium Chypre / Cyprus Espagne / Spain Europe France Italie / Italy Pologne / Poland République tchèque / Czech Republic Royaume-Uni / United Kingdom Slovaquie / Slovakia Slovénie / Slovenia Suisse / Switzerland 2. Actualité du site Eurel / News of the Eurel website * * * * * * 1. Actualité en droit et sociologie des religions / News in law and sociology of religion ALLEMAGNE / GERMANY Articles • ARZHEIMER, Kai, « Ein Märchen aus Tausend und einer Nacht? Kommentar zu dem Artikel von Frederike Wuermeling "Passt die Türkei zur EU und die EU zu Europa?" », K.Z.f.S.S., 2008, 60, 1, 127-139, 32.1. • WUERMELING, Frederike, « Keineswegs ein Märchen aus Tausend und einer Nacht - Replik auf Kai Arzheimers Kommentar zu meinem Aufsatz "Passt die Türkei zur EU und die EU zu Europa? Eine Mehrebenenanalyse auf der Basis der Europäischen Wertestudie », K.Z.f.S.S., 2008, 60, 1, 140-152, 32.1. -

Electrical Power Vision 2040 for Europe

ELECTRICAL POWER VISION 2040 FOR EUROPE A DOCUMENT FROM THE EUREL TASK FORCE ELECTRICAL POWER VISION 2040 Authors of the document EUREL Task Force Electrical Power Vision 2040 Günther Brauner, TU Wien Wiliam D’Haeseleer, KU Leuven Willy Gehrer, EUREL, Past President Wolfgang Glaunsinger, VDE | ETG Thilo Krause, ETH Zürich Henning Kaul, former Member of Bavarian Parliament Martin Kleimaier, VDE | ETG W.L.Kling, TU Eindhoven Horst Michael Prasser, ETH Zürich Ireneus Pyc, Siemens Wolfgang Schröppel, EUREL Waldemar Skomudek, Opele Brussels, December 2012 Title: Nasa Imprint EUREL General Secretariat Rue d‘Arlon 25 1050 Brussels BELGIUM Tel.: +32 2 234 6125 [email protected] Electrical Power Vision 2040 for Europe Study by EUREL Full version 3 © EUREL 2012 Electrical Power Vision 2040 for Europe Table of contents Table of contents...................................................................................................... 5 List of figures............................................................................................................ 9 List of tables ........................................................................................................... 12 1. Introduction and motivation ........................................................................... 13 2. European power generation in the past ........................................................ 17 2.1 Development of power generation in the last two decades in EU27+ ........ 17 2.2 The role of the renewables in Europe today.............................................. -

Young Engineers' Newsletter I-2019

Young Engineers’ Newsletter I-2019 Brussels, April 2019 Dear Students and Young Engineers, here we would like to inform you about this year’s Young Engineers’ activities and we would appreciate if you could promote and participate in these events. EUREL Young Engineers' Seminar - Inside the EU Place Brussels Date 03 to 05 July 2019 Closing date for registration: 7 June 2019 This seminar for Young Engineers is held in Brussels, the capital of Europe, and gives an impression of the work of the European Institutions like the European Parliament, the European Commission or the Council. This annual event is organized by EUREL and is open to all Young Engineers (students and young professionals) of the EUREL member associations. www.eurel.org/yes International Management Cup 2019 Place online, Warsaw Date summer 2019 Closing date for registration: 7 June 2019 Get the chance to match your management skills with students and young professionals from all over Europe! The EUREL International Management Cup is a strategic business simulation game for students and young professionals of Electrical Engineering. Compete online with other teams and increase the share price of your company within 6 weeks. As winning team of the preliminary round, you will be invited to take part in a three-day final round in Warsaw, Poland. www.eurel.org/imc2019 Field trip Portugal 2019 Place Portugal Date 22 to 26 August 2019 Further information coming soon. www.eurel.org/fieldtrip Best regards Sabine Schattke General Secretary EUREL Rue d´Arlon 25 B 1050 Brussels Phone: +32 2 234 61 26 [email protected] www.eurel.org . -

EUREL NEWSLETTER, N° 29 Mai/May 2019

EUREL NEWSLETTER, n° 29 Mai/May 2019 Voici la 29e lettre d'information du site Eurel (données sociologiques et juridiques sur la religion en Europe et au-delà), envoyée deux fois par an. / This is the newsletter # 29 of the Eurel website (sociological and legal data on religions in Europe and beyond) which is sent twice a year. Vous y trouverez, pour de nombreux pays, des informations concernant le droit et les sciences sociales des religions en Europe : les références des livres et articles récemment parus, les nouveaux sites internet, les derniers sondages, les prochains colloques consacrés à ces disciplines. La lettre fournit également des informations sur l'actualité du site / The letter provides academic news concerning law and sociology of religion in many countries of Europe: references of recent books or articles, new websites, just released surveys, and coming meetings. The letter also includes information concerning the latest changes in the Eurel website. 1. Actualité en droit et sociologie des religions / News in law and sociology of religion Europe Pologne/Poland Allemagne/Germany Portugal/Portugal Bulgarie/Bulgaria République tchèque/Czech Republic Espagne/Spain Royaume-Uni/United Kingdom France Russie/Russia Irlande/Ireland Suisse/Switzerland Italie/Italy Canada Lettonie/Latvia 2. Actualité du site Eurel / News of the Eurel website * * * * * 1. Actualité en droit et sociologie des religions / News in law and sociology of religion EUROPE Ouvrages / Books Amiotte-Suchet Laurent, Salzbrunn Monika (dir.), L’événement (im)prévisible. Mobilisations politiques et dynamiques religieuses. Paris, Beauchesne (coll. Dedale), 2019. Avon Dominique, Saint-Martin Isabelle, Tolan John (dir.), Faits religieux et manuels d’histoire. -

Study Energy Transition for Europe

= = bkbodv=qo^kpfqflk=clo=brolmb= ~=åÉÅÉëëáíó=çê=~=ÖêÉÉå=ÇêÉ~ã\= ^==al`rjbkq==colj= =qeb=brobi==q^ph==clo`b= bkbodv=qo^kpfqflk= PREFACE II Preface The study was prepared by the EUREL task Force “Energy Transition”. The task force has members from Austria, Belgium, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania Slovenia and Switzerland. EUREL is the Convention of National Associations of Electrical Engineers of Europe. It was founded in Switzerland in 1972 and in 2013 comprises 9 National Associations in 9 countries. EUREL´s aims and objectives are to facilitate the exchange of information and to foster a wider dis- semination of scientific, technical and related knowledge relevant to electrical engineering. In this way, EUREL contributes to the advancement of scientific and technical knowledge for the benefit of both profession and the public it serves. In so far EUREL is the neutral “lobbyist “of the electrical, electronic and information technology in Europe, which offers its knowhow and knowledge to the public and the political authorities free and on a sound and solid scientific fundament. The best experts from universities, industries and public administration serve in EUREL on a voluntary basis. Publications, advice and support are well re- searched, solidly evaluated and based on the latest results and findings of EUREL´s field of expertise. Title: Nasa Imprint EUREL General Secretariat Rue d‘Arlon 25 1050 Brussels BELGIUM Tel.: +32 2 234 6125 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENT III Table of content Preface ......................................................................................................................................... II Table of content ......................................................................................................................... III 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 2 Current European electrical energy production, consumption, resources and plans . -

The Church in Sweden. Secularisation and Ecumenism As Challenges

Polonia Sacra 20 (2016) nr 2 (43) ∙ s. 23–45 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15633/ps.1686 Anders Ekenberg1 Newman Institute, Uppsala The Church in Sweden. Secularisation and Ecumenism as Challenges “Secularisation” is a concept that is used in many different ways. By secularisation one may, for example, mean a process through which the state ceases to legislate on the basis of religious faith and instead does so on the basis of what is commonly acknowledged. Or a process through which the state ceases to grant special privileges to religious bodies and stops supporting for instance religion ‑based education. Or a pro‑ cess meaning that people cease to hold religious beliefs and uphold reli‑ gious practices. Or transfer of properties from religious or ecclesiastical to civil possession. Or a change meaning that society is no longer under the control of religion. If secularisation means that a society frees itself from coercion or even tyranny of religion over the conscience of individuals, then secu‑ larisation must be valued positively from a Christian point of view. As the Second Vatican Council stated, this is a necessary consequence of the dignity of the human person: 1 Anders Ekenberg, [email protected], Dr. of Theology, Docent (Uppsala University), formerly senior lecturer at Uppsala University, is professor of Theology at the Newman Institute in Uppsala, Sweden. The article is a lecture held at the Pontifical University of John Paul II, Krakow, 16 April 2015. The lecture format has been preserved. 23 Anders Ekenberg It is in accordance with their dignity as persons […] that all men should be at once impelled by nature and also bound by a moral obligation to seek the truth, espe‑ cially religious truth. -

Prayer As a Tool in Swedish Pentecostalism Emir Mahieddin

Prayer as a Tool in Swedish Pentecostalism Emir Mahieddin To cite this version: Emir Mahieddin. Prayer as a Tool in Swedish Pentecostalism. Sociology of prayer, 2015. halshs- 02423943 HAL Id: halshs-02423943 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02423943 Submitted on 23 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Chapter 5 1 2 2 3 Prayer as a Tool in Swedish Pentecostalism 3 4 4 5 Emir Mahieddin 5 6 6 7 7 8 8 9 9 10 Introduction 10 11 11 12 Although Sweden is renowned as one of the most secularised societies in the 12 13 world, the region of Småland, in the south of the country, is a space of strong 13 14 Christian religiosity (Åberg 2007). It is thus considered as the Swedish ‘Bible 14 15 belt’. Jönköping, with its 84,000 inhabitants, is the capital of the region and 15 16 is sometimes called ‘Sweden’s Jerusalem’ or ‘Småland’s Jerusalem’. In 1861 the 16 17 Jönköping Evangelical Association (Jönköpings missionsförening) was founded. 17 18 This new religious association based on pietistic Christian principles attracted 18 19 to town many inhabitants from the county of Jönköping and from the whole 19 20 region. -

4Th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar FGAN J&*J OVDS EUREL, URSI, DGON, IEEE

Proceedings 4th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar EUSAR 4-6 June 2002, Cologne, Germany incl. CD ROM i i ••••• , •<. Organized by ITG / VDI J J astrium FGAN &* OVDS • • • Htiropr.au Aoronife&IifDeff ISP and Sjwrr: Cxin>piiiiy • • • technically sponsored by EUREL, URSI, DGON, IEEE UB/TIB Hannover 89 123 857 031 VDE VERLAG GMBH • Berlin • Offenbach Contents Spaceborne SAR Systems I 1 RADARSAT-2 Program Update (new paper) 25 L. Brule, Canadian Space Agency, Canada; H. Baeggli, MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates, Ltd., Canada 2 Analysis of Bistatic Configurations for Spaceborne SAR Interferometry 29 H. Fiedler, G. Krieger, F. Jochim, M. Kirschner, A. Moreira, Deutsches Zentrum fur Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR), Germany 3 PARIS Mode in a SAR Mission 33 A. P. Thompson, C. H. Mathew, Astrium Ltd, Earth Observation & Science, UK Spaceborne SAR Systems II 4 The RADARSAT-2&3 Topographic Mission 37 N. Evans, P. Lee, MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates, Ltd, Canada 5 Potentials of Reflector Antenna Technology for a Fully Polarimetric L-band Spaceborne SAR Instrument Targeting Land Applications 41 R. Schroder, K.-H. Zeller, H. SQI3, Deutsches Zentrum fur Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR), Germany 6 Multi-Mode SAR System Model Design for Small Satellite Platform 45 Y. K. Kwag, Hankuk Aviation University, Korea 7 TerraSAR X - Design and Performance 49 M. Suess, S. Riegger, W. Pitz, Astrium GmbH, Friedrichshafen, Germany; R. Werninghaus, DLR, Bonn, Germany Wide Bandwidth and Low Frequency SAR 8 Ultra-Wideband Multi-static Synthetic Aperture Radar for the Detection and Location of Land Mines 53 D. J. Lloyd, D. Longstaff, University of Queensland, Australia 9 Some Results on Detection of Targets Deployed in Hide under Foliage 57 A. -

Report 2018-2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 c/o REGUS EU Commission Schuman Square 6/5 B-1040 Brussels +32 2 234 78 78 [email protected] www. feani.org What is FEANI ? ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 FEANI NATIONAL MEMBERS IS NO SE FI EE RU IE DK RU UK NL PL KZ BE DE CZ UA FR SK CH AT HU SI RO HR PT SER AZ ES IT BG MK TR GR MT CYCY FEANI NATIONAL MEMBERS FEANI NATIONAL MEMBERS 3 ÖIAV – Österreichischer Ingenieur-und KasZEE – Kazachstan Society of Engineering AT Architekten-Verein KZ Education CIBIC – Comité des Ingénieurs Belges / IMI – Engineering Institution of Macedonia BE Belgisch Ingenieurscomité MK FNTS – Federation of Scientific Technical COE - Chamber of Engineers BG Unions in Bulgaria MT SIA – Swiss Society of Engineers and CH Architects NL KIVI – Koninklijk Instituut Van Ingenieurs STV/UTS – Swiss Engineering STV IS NITO – The Norwegian Society of Engineers and Technologists ETEK – Technical Chamber of Cyprus CY NO TEKNA – The Norwegian Society of Chartered Scientific and Academic Professionals CSVTS – Czech Association of Scientific and Technical Societies NOT – Polish Federation of Engineering CZ CKAIT – Czech Chamber of Chartered PL Associations Engineers and Technicians NO SE FI DVT – Deutscher Verband Technisch- Ordem Dos Engenheiros DE Wissenschaftlicher Vereine PT AGIR – The General Association of Engineers EE RU IDA – Ingeniørforeningen i Danmark DK RO in Romania IE DK SITS – Union of Engineers and Technicians EAE – Estonian Association of Engineers EE RS of Serbia RU UK IIE – Instituto de la Ingenieriá de España NL INGITE – Instituto -

Electrical Power Vision 2040 for Europe

ELECTRICAL POWER VISION 2040 FOR EUROPE A DOCUMENT FROM THE EUREL TASK FORCE ELECTRICAL POWER VISION 2040 Authors of the document EUREL Task Force Electrical Power Vision 2040 Günther Brauner, TU Wien Wiliam D’Haeseleer, KU Leuven Willy Gehrer, EUREL, Past President Wolfgang Glaunsinger, VDE | ETG Thilo Krause, ETH Zürich Henning Kaul, former Member of Bavarian Parliament Martin Kleimaier, VDE | ETG W. L. Kling, TU Eindhoven Horst Michael Prasser, ETH Zürich Ireneus Pyc, Siemens Wolfgang Schröppel, EUREL Waldemar Skomudek, Opele Brussels, February 2013 Title: Nasa Imprint EUREL General Secretariat Rue d‘Arlon 25 1050 Brussels BELGIUM Tel.: +32 2 234 6125 [email protected] Electrical Power Vision 2040 for Europe Study by EUREL Short version 3 © EUREL 2013 Electrical Power Vision 2040 for Europe Table of contents 1. Introduction and motivation ............................................................................. 7 2. European power generation in the past ......................................................... 8 3. Changing role of electric power..................................................................... 10 4. Environmental, economic and political requirements on the supply security of electrical power........................................................................................... 13 5. European electrical power demand in the next decades ............................. 15 6. Options for future bulk power transport and supply security of power ..... 17 7. Options for future power production............................................................ -

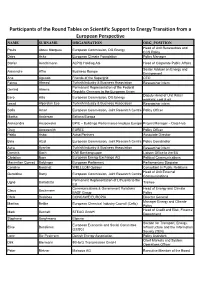

Participants of the Round Tables on Scientific Support to Energy

Participants of the Round Tables on Scientific Support to Energy Transition from a European Perspective NAME SURNAME ORGANISATION ORG_POSITION Head of Unit Renewables and Paula Abreu Marques European Commission, DG Energy CCS Policy Dries Acke European Climate Foundation Policy Manager Stefan Aeschimann ALPIQ Holding AG Head of Corporate Public Affairs Senior Adviser on Energy and Alexandre Affre Business Europe Environment Ana Aguado Friends of the Supergrid CEO Fatma Ahmed Turkish Industry & Business Association Researcher intern Permanent Representation of the Federal Gerlind Ahrens Republic Germany to the European Union Deputy Head of Unit Retail Eero Ailio European Commission, DG Energy markets; coal & oil Ismail Alparslan Ece Turkish Industry & Business Association Researcher intern Sofia Amor European Commission, Joint Research Centre Policy Officer Marika Andersen Bellona Europa Aleksandra Arcipowska BPIE – Buildings Performance Institute Europe Project Manager – Data Hub Greg Arrowsmith EUREC Policy Officer Pablo Asbo Avisa Partners Associate Director Bela Atzel European Commission, Joint Research Centre Policy Coordinator Ayca Ayanlar Turkish Industry & Business Association Researcher intern Dominik Bach KfW Bankengruppe Liaison Office to the EU Christian Baer European Energy Exchange AG Political Communications Maximilian Conrad Baldinger European Parliament Parliamentary Stagiaire Coraline Bardinat WELLCOM Opinion Consultant in Public Relations Head of Unit External Geraldine Barry European Commission, Joint Research Centre