Historical Report on Aberlady

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fentoun Green

FENTOUN GREEN GULLANE CALA HOMES FENTOUN GREEN OFF MAIN STREET GULLANE EAST LOTHIAN EH31 2EE CALA.CO.UK Local photography of Gullane Beach is courtesy of Richard Elliott FENTOUN GREEN ESCAPE TO CALMER SURROUNDINGS Situated to the eastern edge of the idyllic seaside haven of Gullane, this select development of light and spacious family homes enjoys a tranquil semi-rural feel, with picturesque views of the mature tree-lined setting and stunning countryside beyond. Part of CALA’s beautiful East Lothian Range, Fentoun Green features an exclusive collection of 3, 4 and 5 bedroom detached and semi-detached homes. Boasting plentiful open green spaces, you can appreciate a superior quality of life in relaxed surroundings, with the convenience of everyday amenities, top performing schools and commuter links still in close reach. Local photography is courtesy of Chris Robson Photography 3 GULLANE A LIFE OF COASTAL BLISS You can relax or be as active as you like with Gullane’s many outdoor pursuits, including mile after mile of nature walks, award-winning beaches and world-famous golf courses. The scenic John Muir Way passes by Fentoun Green, while the golden sands of Gullane Bents and Aberlady Bay are the perfect settings for taking in the beautiful coastline. Or discover the trails, café and bar at Archerfield Walled Garden, where you can sample the famous Archerfield Craft Ales. Every year, golf enthusiasts from around the globe flock to the championship links courses of Gullane and world-famous Muirfield, as well as the highly regarded clubs of Archerfield and Renaissance nearby. Gullane’s quaint main street has a selection of shops, top eateries, cafés and other amenities, while the desirable town of North Berwick is only a few miles away, as are plentiful family attractions including Dirleton Castle, the Scottish Seabird Centre, National Museum of Flight and Seacliff Stables. -

OUTREACH November 2019 Pages Copy

ABERLADY CHURCH 25TH NOVEMBER 2019 OUTREACH You are warmly invited to join us in the SACRAMENT OF HOLY COMMUNION Aberlady Parish Church Sunday 25th NOVEMBER 2019 11.15am All welcome SC004580 Church of Scotland 1 ABERLADY CHURCH 25TH NOVEMBER 2019 SUNDAY THIRTY A short, informal All Age Service led by the Aberlady Worship Team in Aberlady Kirk Stables at 8.45am on the third Sunday of each month, followed by coffee/tea, a chat and something to eat. Dates for your diary are: 17th November, 15th December, (2020) 19th January, 16th February, 15th March All are welcome. A big thank you from the Worship Team to all who have attended our early Service during the past year. Hazel Phisatory HARVEST SERVICE Our Harvest Service was held on 6th October. I would like to thank all who helped decorate the church the day before the Service and to all who donated goods or cash. All perishable items were delivered to the Cyrenians in Edinburgh and non perishable items together with cash donations of £30 were delivered to the local Food Bank in Tranent. Hazel Phisatory, Session Clerk. Bethany Care Van - Now that the colder nights are coming in again, there is an increased need for warm clothing, blankets and sleeping bags to distribute to homeless people in Edinburgh. If you have any such items and are willing to donate them to the Care Van, please drop them off at the Kirk Stables where I will collect them. Alternatively, I am happy to collect them from your home - just let me know on 01875 853 137, Many thanks. -

Issue No 3 – Spring 1978

The Edinburgh Geologist March 1978 '.:.,' Editor's Comments One year a~ter its ~irst appearance, the third issue o~ the Edinburgh Geologist has been produced. I have always hoped that the magazine would be varied and so I am very pleased to see several new ideas in this issue - a crossword, two book reviews and a poem. These combined with the main articles cover a range o~ geological topics and it is hoped that everyone in the Society will ~ind something o~ interest. I would like to ask potential contributors to contact me in good time to discuss ideas they may have ~or the next issue which is planned ~or October/November this year. I would like to have dra~t copies o~ the articles by the end of September to allow for editing and discussion. My thanks are due to all contributors to this issue, and also to Dr. Mykura and Mr. Butche'r who produced the second issue of The Edinburgh Geologist in my absence last year. Helena Butler (Editor) P.S. From the 23rd. March, my home address will be 9 Fox Springs Crescent, Edinburgh 10. Tel. No. 445-3705. THE CORAL FAUNA OF THE MIDDL~ LONGCRAIG LIMESTONE AT ABERLADY BAY Aberlady Bay, situated on the south shore o~ the Firth of Forth some 11 miles east of Edinburgh, has long been recognised as one o~ the classic localities in the Midland Valley ~or the study of Lower Carboniferous/ 1. • Rugose corals. It was rather surprising therefore, to find that in the available geological literature, only six species were recorded from the locality. -

7. Some Lesser Lothian Streams This Is A

7. Some Lesser Lothian Streams This is a ‘wash-up’ section, in which I look briefly at a number of small streams, mostly called burns, which flow directly to the sea or the Firth of Forth, but which in terms of discharge rate are mainly an order of magnitude smaller than the rivers looked at so far. For each, I give a short account of the course and pick out a few features of interest, presenting photographs as seems appropriate. Starting furthest to the east, the streams dealt with are as follows: 1. Dunglas Burn 2. Thornton Burn 3. Spott Burn 4. Biel Water 5. East Peffer Burn 6. West Peffer Burn 7. Niddrie Burn 8. Braid Burn 9. Midhope Burn As shall become clear, some of these streams change their names more than once along their lengths and most are formed at the junction of other named streams, but hopefully any confusion will be resolved in the accounts which follow. 7.1 The Dunglas Burn The stream begins life as the Oldhamstocks Burn which collects water from a number of springs on Monynut Edge, the eastern flank of the Lammermuir Hills. No one of these feeders dominates, so the source is taken as where the name Oldhamstocks Burn appears, at grid point NT 713 699, close to the 200m contour. After flowing c3km east, the name changes to the Dunglas Burn which flows slightly north-east in a deep, steep- sided valley for just over 7km to reach the sea. For the downstream part of its course the burn is the boundary between the Lothians and the Scottish Borders, but upstream it flows in the former region. -

Golfer's Guide for the United Kingdom

Gold Medals Awarded at International Exhibitions. AS USED BY HUNDREDS THE OF CHAMPION UNSOLICITED PLAYERS. TESTIMONIALS. Every Ball Guaranteed in Properly Matured Condition. Price Ms. per dozen. The Farthest Driving- and Surest Putting- Ball in the Market. THORNTON GOLF CLUBS. All Clubs made from Best Materials, Highly Finished. CLUB COVERS AND CASES. Specialities in aboue possessing distinct improuements in utility and durability. Every Article used in Golf in Perfection of Quality and Moderation in Price. PKICE LIST ON APPLICATION. THORNTON & CO., Golf Appliance Manufacturers, 78 PRINCES STREET, EDINBURGH. BRANCHES—, LEEDS, BRADFORD, aqd BELFAST. ' SPECI A L.1TIE S. WEDDING PRESEF ELECTRO-SILVER PLATE JAMES GRAY & SON'S NEW STOCK of SILVER-PLATED TEA and COFFEE SETS, AFTER- NOON TEA SETS, CASES "I FRUIT and FISH KNIVES and FORKS, in Pearl or Ivory Handles, FINE CASES OF MEAT AND FISH CARVERS, TEA and FELLY SPOONS In CASES. CASES of SALTS, CREAM, and SUGAR STANDS. ENTREE DISHES, TABLE CUTLERY, and many very Attractive and Useful Novelties, suitable for Marriage and other Present*. NEW OIL LAMPS. JAMES GRAY & SON Special De*lgn« made for their Exclusive Sale, In FINEST HUNGARIAN CHINA, ARTISTIC TABLE and FLOOR EXTENSION [.AMI'S In Brass, Copper,and Wrougnt-Iroti, Also a very Large Selection of LAMP SHADES, NBWMT DJUUQWB, vary moderate In price. The Largest and most Clioieo Solootion in Scotland, and unequallod in value. TnspecHon Invited. TAb&ral Heady Money Dlgcount. KITCHEN RANGES. JAMES GRAY & SON Would draw attention to their IMPROVED CONVERTIBLE CLOSE or OPEN FIRE RANGE, which is a Speciality, constructed on Liu :best principles FOR HEATINQ AND ECONOMY IN FUEL. -

GRAVEYARD MONUMENTS in EAST LOTHIAN 213 T Setona 4

GRAVEYARD MONUMENT EASN SI T LOTHIAN by ANGUS GRAHAM, M.A., F.S.A., F.S.A.SCOT. INTRODUCTORY THE purpos thif eo s pape amplifo t s ri informatioe yth graveyare th n no d monuments of East Lothian that has been published by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.1 The Commissioners made their survey as long ago as 1913, and at that time their policy was to describe all pre-Reformation tombstones but, of the later material, to include only such monuments as bore heraldic device possesser so d some very notable artisti historicar co l interest thein I . r recent Inventories, however, they have included all graveyard monuments which are earlier in date than 1707, and the same principle has accordingly been followed here wit additioe latey hth an r f eighteenth-centurno y material which called par- ticularly for record, as well as some monuments inside churches when these exempli- fied types whic ordinarile har witt graveyardsyn hme i insignie Th . incorporatef ao d trades othed an , r emblems relate deceasea o dt d person's calling treatee ar , d separ- n appendixa atel n i y ; this material extends inte nineteentth o h centurye Th . description individuaf o s l monuments, whic takee har n paris parisy hb alphan hi - betical order precedee ar , reviea generae y th b df w o l resultsurveye th f so , with observations on some points of interest. To avoid typographical difficulties, all inscriptions are reproduced in capital letters irrespectiv nature scripe th th f whicf n eo i eto h the actualle yar y cut. -

Scotland ; Picturesque, Historical, Descriptive

ITritjr mttr its Rrimtjr. HE sea-port and town of Leith, anciently Inverleith, 1 at the debouch of the Water of Leith stream, which flows through the harbour into the Frith of Forth, is nearly a mile and a half from Edinburgh. The town is a curious motley group of narrow streets, in which are numbers of old tenements, the architecture and interiors of which indicate the affluence of the former possessors. Although a place of considerable antiquity, and mentioned as Inverleith in David I.'s charter of Holyrood, the commercial importance of Leith dates only from the fourteenth century, when the magistrates of Edinburgh obtained a grant of the harbour and mills from King Robert Bruce for the annual payment of fifty-two merks. This appears to have been one of the first of those transactions by which the citizens of Edinburgh acquired the complete mastery over Leith, and they are accused of exercising their power in a most tyrannical manner. So completely, indeed, were the Town-Council of Edinburgh resolved to enslave Leith, that the inhabitants were not allowed to have shops or warehouses, and even inns or hostelries could be arbitrarily prohibited. This power was obtained in a very peculiar maimer. In 1398 and 1413, Sir Robert Logan of Restalrig, then superior of the town, disputed the right of the Edinburgh corporation to the use of the banks of the Water of Leith, and the property was purchased from him at a considerable sum. This avaricious baron afterwards caused an infinitude of trouble to the Town-Council on legal points, but they were resolved to be the absolute rulers of Leith at any cost; and they advanced from their treasury a large sum, for which Logan granted a bond, placing Leith completely at the disposal of the Edinburgh Corporation, and retaining all the before-mentioned restrictions. -

North Berwick Coastal a Statistical Overview Population 12,515 People Live in the North Berwick Coastal Ward

North Berwick Coastal a statistical overview Population 12,515 people live in the North Berwick Coastal ward 13% of the population of East Lothian Aberlady remaining 9% rural Dirleton / Fenton areas 11% • 6,605 in North Berwick Barns 7% • 818 in Dirleton / Fenton Barns • 2,568 in Gullane • 1,166 in Aberlady Gullane 21% North Berwick 53% Population growth Between 2001 and 2011 the population of East Lothian grew by almost 11% • Across the North Berwick Coastal ward the population grew slightly slower – increasing by 10.3% But the growth has not been even across the area: 40% 34% 30% 20% 18% 10% 6% 4% 0% North Berwick Gullane Aberlady Rural areas Population North Berwick East Lothian Scotland Coastal Ward children & young people 18% 19% 17% working age (16-64 yrs) 57% 63% 66% pensionable age (65+) 25% 18% 17% • Gullane has the lowest percentage of working age people across East Lothian (52%) • Aberlady has one of the highest concentrations of children and young people across the county (22%) 4 key objectives of The East Lothian Plan 1. To reduce inequalities across and within our communities 2. To support people to develop the resilience they need to lead a fulfilling life 3. To develop a sustainable economy across the area 4. To ensure safe and vibrant communities Measuring Deprivation Tackling poverty In the North Berwick Coastal ward almost 2/3 of all households have weekly incomes above the East Lothian average • average household income varies by almost £270 per week between the most affluent areas and the least • In parts of North -

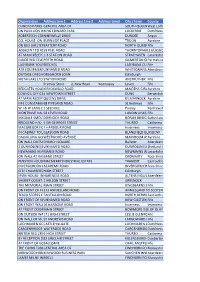

Members' Library Service Request Form

Members’ Library Service Request Form Date of Document 03/07/15 Originator Depute Chief Exec - Partnerships & Comm Svcs Originator’s Ref (if any) Document Title Building Warrants Issued under Delegated Powers between 1st June and 30th June 2015 Please indicate if access to the document is to be “unrestricted” or “restricted”, with regard to the terms of the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985. Unrestricted Restricted If the document is “restricted”, please state on what grounds (click on grey area for drop- down menu): For Publication Please indicate which committee this document should be recorded into (click on grey area for drop-down menu): Planning Committee Additional information: Authorised By Monica Patterson Designation Depute Chief Exec - Part & Com Svcs Date 03/07/15 For Office Use Only: Library Reference 122/15 Date Received 03/07/15 Bulletin Jul 15 Building Warrants Issued under Delegated Powers between 1 June 2015 and 30 June 2015 BW 05/01019/BW_A Proposal Amend 05/01019/BW - Minor amendments to internal layouts Address of Glenisla Abbotsford Road North Berwick East Lothian EH39 5DB Mr And Mrs D Petrie Applicant Glenisla Abbotsford Road North Berwick East Lothian EH39 5DB Agent Estimated Cost of Works 0 BW 06/01013/BW_H Proposal Amend 06/01013/BW - Proposed internal alterations to unit C3 (plot 26) to replace shower room with dressing room Address of Under Bolton Farm Steading Bolton Haddington East Lothian EH41 4HL Ogilvie Homes Ltd Applicant Ogilvie House Pirnhall Business Park Stirling FK7 8ES Agent Estimated Cost of Works 0 BW 09/00427/BW_A Proposal Amend 09/00427/BW - Double glazed upvc door/window unit with precast concrete step to dining room replaced with double glazed timber bifold door and timber deck/landing. -

Scottish Birds

SCOTTISH BIRDS THE JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' CLUB Volume 7 No. 4 WINTER 1972 Price SOp John Gooders watchingTawny Eagles inThebes Mr. John Gooders, the celebrated ornithologist and Editor of 'Birds of the World', is seen using his new Zeiss 10 x40B binoculars. Mr. Gooders writes: " I stare through binoculars all day long for weeks on end without eyestrain - try that with any binoculars other than West German Zeiss. The 10 x 40B meets all my other needs too; high twilight power for birds at dawn and dusk, superb resolution for feather by feather examination, and wide field of view. With no external moving parts they stand the rough treatment that studying birds in marsh, snow and desert involves - I can even use them with sunglasses without losing performance, Zeiss binocular are not cheap - but they are recognised as the best by every ornithologist I IqlOW. The 10 x 40B is the perfect glass for birdwatching'''. Details from the sole UK agents for Carl Zeiss, West Germany, Degenhardt & Co. Ltd., 31 /36 Foley Street, London W1P 8AP. Telephone 01·636 8050 (15 lines) " I ~ megenhardt o B S E R V E & CoO N S'ER V E BINOCULARS TELESCOPES SPECIAL DISCOUNT OFFER OF ~6 33}1% POST/INSURED FREE Retatl price Our price SWIFT AUDUBON Mk. 11 8.5 x 44 £49.50 £33.50 SWIFT SARATOGA Mk. 11 8 x 40 £32.50 £23.90 GRAND PRIX 8 x 40 Mk. I £27.40 £20.10 SWIFT NEWPORT Mk. 11 10 x 50 £37.50 £26.25 SWIFT SUPER TECNAR 8 x 40 £18.85 £13.90 ZEISS JENA JENOPTEN 8 x 30 £32.50 £19.95 CARl ZEISS 8 x 30B Dialyt £103.15 £74.00 CARl ZEISS 10 x 40B Dialyt £119.62 £85.00 LEITZ 8 x 40B Hard Case £131.30 £97.30 LEITZ 10 x 40 Hard Case £124.30 £91.75 ROSS STEPRUVA 9 x 35 £51.44 £39.00 HABICHT DIANA 10 x 40 W/A (best model on market under £61) £60.61 £48.41 Nickel Supra Telescope 15 x 60 x 60 £66.00 £49.50 Hertel & Reuss Televari 25 x 60 x 60 £63.90 £48.00 and the Birdwatcher's choice the superb HERON 8 x 40 just £13.00 (leaflet available). -

I General Area of South Quee

Organisation Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line3 City / town County DUNDAS PARKS GOLFGENERAL CLUB- AREA IN CLUBHOUSE OF AT MAIN RECEPTION SOUTH QUEENSFERRYWest Lothian ON PAVILLION WALL,KING 100M EDWARD FROM PARK 3G PITCH LOCKERBIE Dumfriesshire ROBERTSON CONSTRUCTION-NINEWELLS DRIVE NINEWELLS HOSPITAL*** DUNDEE Angus CCL HOUSE- ON WALLBURNSIDE BETWEEN PLACE AG PETERS & MACKAY BROS GARAGE TROON Ayrshire ON BUS SHELTERBATTERY BESIDE THE ROAD ALBERT HOTEL NORTH QUEENSFERRYFife INVERKEITHIN ADJACENT TO #5959 PEEL PEEL ROAD ROAD . NORTH OF ENT TO TRAIN STATION THORNTONHALL GLASGOW AT MAIN RECEPTION1-3 STATION ROAD STRATHAVEN Lanarkshire INSIDE RED TELEPHONEPERTH ROADBOX GILMERTON CRIEFFPerthshire LADYBANK YOUTHBEECHES CLUB- ON OUTSIDE WALL LADYBANK CUPARFife ATR EQUIPMENTUNNAMED SOLUTIONS ROAD (TAMALA)- IN WORKSHOP OFFICE WHITECAIRNS ABERDEENAberdeenshire OUTSIDE DREGHORNDREGHORN LOAN HALL LOAN Edinburgh METAFLAKE LTD UNITSTATION 2- ON ROAD WALL AT ENTRANCE GATE ANSTRUTHER Fife Premier Store 2, New Road Kennoway Leven Fife REDGATES HOLIDAYKIRKOSWALD PARK- TO LHSROAD OF RECEPTION DOOR MAIDENS GIRVANAyrshire COUNCIL OFFICES-4 NEWTOWN ON EXT WALL STREET BETWEEN TWO ENTRANCE DOORS DUNS Berwickshire AT MAIN RECEPTIONQUEENS OF AYRSHIRE DRIVE ATHLETICS ARENA KILMARNOCK Ayrshire FIFE CONSTABULARY68 PIPELAND ST ANDREWS ROAD POLICE STATION- AT RECEPTION St Andrews Fife W J & W LANG LTD-1 SEEDHILL IN 1ST AID ROOM Paisley Renfrewshire MONTRAVE HALL-58 TO LEVEN RHS OFROAD BUILDING LUNDIN LINKS LEVENFife MIGDALE SMOLTDORNOCH LTD- ON WALL ROAD AT -

Founding Fellows

Founding Members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Alexander Abercromby, Lord Abercromby William Alexander John Amyatt James Anderson John Anderson Thomas Anderson Archibald Arthur William Macleod Bannatyne, formerly Macleod, Lord Bannatyne William Barron (or Baron) James Beattie Giovanni Battista Beccaria Benjamin Bell of Hunthill Joseph Black Hugh Blair James Hunter Blair (until 1777, Hunter), Robert Blair, Lord Avontoun Gilbert Blane of Blanefield Auguste Denis Fougeroux de Bondaroy Ebenezer Brownrigg John Bruce of Grangehill and Falkland Robert Bruce of Kennet, Lord Kennet Patrick Brydone James Byres of Tonley George Campbell John Fletcher- Campbell (until 1779 Fletcher) John Campbell of Stonefield, Lord Stonefield Ilay Campbell, Lord Succoth Petrus Camper Giovanni Battista Carburi Alexander Carlyle John Chalmers William Chalmers John Clerk of Eldin John Clerk of Pennycuik John Cook of Newburn Patrick Copland William Craig, Lord Craig Lorentz Florenz Frederick Von Crell Andrew Crosbie of Holm Henry Cullen William Cullen Robert Cullen, Lord Cullen Alexander Cumming Patrick Cumming (Cumin) John Dalrymple of Cousland and Cranstoun, or Dalrymple Hamilton MacGill Andrew Dalzel (Dalziel) John Davidson of Stewartfield and Haltree Alexander Dick of Prestonfield Alexander Donaldson James Dunbar Andrew Duncan Robert Dundas of Arniston Robert Dundas, Lord Arniston Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville James Edgar James Edmonstone of Newton David Erskine Adam Ferguson James Ferguson of Pitfour Adam Fergusson of Kilkerran George Fergusson, Lord Hermand