Bresson and Others

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANGELS' SHARE – Ein Schluck Für Die Engel

Kirchen + Kino. DER FILMTIPP 7. Staffel, Oktober 2013 – Mai 2014, 4. Film : „Angels’ Share – Ein Schluck für die Engel “ ANGELS’ SHARE – Ein Schluck für die Engel GB/F/B/I 2012 Länge: 101 Minuten FSK: ab 12 Jahren Originalsprache: Englisch Originaltitel: The Angels’ Share Regie: Ken Loach Drehbuch: Paul Laverty Produktion: Rebecca O’Brien Kamera: Robbie Ryan Schnitt: Jonathan Morris Musik: George Fenton Besetzung: Paul Brannigan (Robbie), John Henshaw (Harry, Sozialarbeiter), Jasmin Riggins (Mo), Gary Maitland (Albert), William Ruane (Rhino), Siobhan Reilly (Leonie, Robbies Freundin), Roger Allam (Thaddeus, Whiskyhändler) Auszeichnungen: Festival de Cannes: „Prix du Jury“ Empfehlung: Von www.medientipp.ch. – Programm-, Film- und Medienhinweise zu Kirche, Religion und Gesellschaft wurde der Film ausgezeichnet als Film des Monats Dezember 2012 mit der Begründung: „Eine bittersüsse Komödie über Robbie, der in eine Familien-Fehde verwickelt ist und alles tut, um sich daraus zu befreien. Als er in der Geburtsabteilung zum ersten Mal den kleinen Luke auf dem Arm hält, ist er ist überwältigt. Der junge Mann schwört, dass seinem Sohn nicht dasselbe Schicksal blühen wird. Mit viel Fantasie und Herzblut begibt sich Robbie auf einen neuen Lebensweg. Statt weiter Gewalt und Rache zu säen, entscheidet er sich für ein neues Hobby: dem Degustieren mit feiner Nase und findigem Gaumen. Die überraschende Hinwendung zum Alkohol – nicht Wein, sondern Malt Whiskey vom Feinsten – eröffnet eine neue berufliche Perspektive. Doch bevor Robbie sein Hobby zur Profession machen kann, muss er in den hohen Norden Schottlands reisen und an einer legendären Whiskey-Verkostung teilnehmen. Dabei begleiten ihn Rhino, Albert und Mo in typischer Kilt-Verkleidung. -

71 Ans De Festival De Cannes Karine VIGNERON

71 ans de Festival de Cannes Titre Auteur Editeur Année Localisation Cote Les Années Cannes Jean Marie Gustave Le Hatier 1987 CTLes (Exclu W 5828 Clézio du prêt) Festival de Cannes : stars et reporters Jean-François Téaldi Ed du ricochet 1995 CTLes (Prêt) W 4-9591 Aux marches du palais : Le Festival de Cannes sous le regard des Ministère de la culture et La 2001 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Mar sciences sociales de la communication Documentation française Cannes memories 1939-2002 : la grande histoire du Festival : Montreuil Média 2002 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Can l’album officiel du 55ème anniversaire business & (Exclu du prêt) partners Le festival de Cannes sur la scène internationale Loredana Latil Nouveau monde 2005 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) LAT Cannes Yves Alion L’Harmattan 2007 Magasin W 4-27856 (Exclu du prêt) En haut des marches, le cinéma : vitrine, marché ou dernier refuge Isabelle Danel Scrineo 2007 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) DAN du glamour, à 60 ans le Festival de Cannes brille avec le cinéma Cannes Auguste Traverso Cahiers du 2007 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Can cinéma (Exclu du prêt) Hollywood in Cannes : The history of a love-hate relationship Christian Jungen Amsterdam 2014 Magasin W 32950 University press Sélection officielle Thierry Frémaux Grasset 2017 Magasin W 32430 Ces années-là : 70 chroniques pour 70 éditions du Festival de Stock 2017 Magasin W 32441 Cannes La Quinzaine des réalisateurs à Cannes : cinéma en liberté (1969- Ed de la 1993 Magasin W 4-8679 1993) Martinière (Exclu du prêt) Cannes, cris et chuchotements Michel Pascal -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Festival Schedule

T H E n OR T HWEST FILM CE n TER / p ORTL a n D a R T M US E U M p RESE n TS 3 3 R D p ortl a n D I n ter n a tio n a L film festi v a L S p O n SORED BY: THE OREGO n I a n / R E G a L C I n EM a S F E BR U a R Y 1 1 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 0 WELCOME Welcome to the Northwest Film Center’s 33rd annual showcase of new world cinema. Like our Northwest Film & Video Festival, which celebrates the unique visions of artists in our community, PIFF seeks to engage, educate, entertain and challenge. We invite you to explore and celebrate not only the art of film, but also the world around you. It is said that film is a universal language—able to transcend geographic, political and cultural boundaries in a singular fashion. In the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous observation, “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler who is foreign,” this year’s films allow us to discover what unites rather than what divides. The Festival also unites our community, bringing together culturally diverse audiences, a remarkable cross-section of cinematic voices, public and private funders of the arts, corporate sponsors and global film industry members. This fabulous ecology makes the event possible, and we wish our credits at the back of the program could better convey our deep appreci- ation of all who help make the Festival happen. -

Filmar As Sensações

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOSOFIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM FILOSOFIA Luiz Roberto Takayama Filmar as sensações: Cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson São Paulo 2012 Luiz Roberto Takayama Filmar as sensações: Cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson Tese apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em Filosofia do Departamento de Filosofia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para obtenção do título de Doutor em Filosofia sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Luiz Fernando B. Franklin de Matos. São Paulo 2012 Ao pequeno Hiro, grande herói, dedico esse trabalho. “Tão longe que se vá, tão alto que se suba, é preciso começar por um simples passo.” Shitao. Agradecimentos À CAPES, pela bolsa concedida. À Marie, Maria Helena, Geni e a todo o pessoal da secretaria, pela eficiência e por todo o apoio. Aos professores Ricardo Fabbrini e Vladimir Safatle, pela participação na banca de qualificação. Ao professor Franklin de Matos, meu orientador e mestre de todas as horas. A Jorge Luiz M. Villela, pelo incentivo constante e pelo abstract. A José Henrique N. Macedo, aquele que ama o cinema. Ao Dr. Ricardo Zanetti e equipe, a quem devo a vida de minha esposa e de meu filho. Aos meus familiares, por tudo e sempre. RESUMO TAKAYAMA, L. R. Filmar as sensações: cinema e pintura na obra de Robert Bresson. 2012. 186 f. Tese (Doutorado) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas. Departamento de Filosofia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2012. -

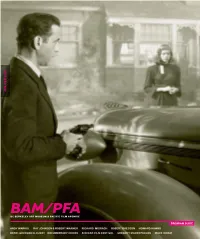

BAM/PFA Program Guide

B 2012 B E N/F A J UC BERKELEY ART MUSEum & PacIFIC FILM ARCHIVE PROGRAM GUIDE AnDY WARHOL RAY JOHNSON & ROBERT WARNER RICHARD MISRACH rOBERT BRESSON hOWARD HAWKS HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOt dOCUMENTARY VOICES aFRICAN FILM FESTIVAL GREGORY MARKOPOULOS mARK ISHAM BAM/PFA EXHIBITIONS & FILM SERIES The ReaDinG room P. 4 ANDY Warhol: PolaroiDS / MATRIX 240 P. 5 Tables OF Content: Ray Johnson anD Robert Warner Bob Box ArchiVE / MATRIX 241 P. 6 Abstract Expressionisms: PaintinGS anD DrawinGS from the collection P. 7 Himalayan PilGrimaGE: Journey to the LanD of Snows P. 8 SilKE Otto-Knapp: A liGht in the moon / MATRIX 239 P. 8 Sun WorKS P. 9 1 1991: The OAKlanD-BerKeley Fire Aftermath, PhotoGraphs by RicharD Misrach P. 9 RicharD Misrach: PhotoGraphs from the Collection State of MinD: New California Art circa 1970 P. 10 THOM FaulDers: BAMscape Henri-GeorGes ClouZot: The Cinema of Disenchantment P. 12 Film 50: History of Cinema, Film anD the Other Arts P. 14 BehinD the Scenes: The Art anD Craft of Cinema Composer MARK Isham P. 15 African film festiVal 2012 P. 16 ScreenaGers: 14th Annual Bay Area HIGH School Film anD ViDeo FestiVal P. 17 HowarD HawKS: The Measure of Man P. 18 Austere Perfectionism: The Films of Robert Bresson P. 21 Documentary Voices P. 24 SeconDS of Eternity: The Films of GreGory J. MarKopoulos P. 25 DiZZY HeiGhts: Silent Cinema anD Life in the Air P. 26 Cover GET MORE The Big Sleep, 3.13.12. See Hawks series, p. 18. Want the latest program updates and event reminders in your inbox? Sign up to receive our monthly e-newsletter, weekly film update, 1. -

En Mørk Fortid for En Lysere Fremtid?

En mørk fortid for en lysere fremtid? En studie av historiebruk med fokus på Steilneset minnested i Vardø. Av Weronica Melbø-Jørgensen Masteroppgave for Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie ved det humanistiske fakultet. UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Våren 2017 II En mørk fortid for en lysere fremtid? En studie av historiebruk med fokus på Steilneset minnested i Vardø. III © Weronica Melbø-Jørgensen 2017 En mørk fortid for en lysere fremtid? En studie av historiebruk med fokus på Steilneset minnested i Vardø. Forsidebilde: Minnehallen og kunstverkbygget på Steilneset i Vardø ©Foto: Harald Bech-Hanssen / Statens vegvesen http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Forord En gang på ungdomsskolen lånte jeg min første bok om trolldom. Interessen for temaet har siden da vokst og utviklet seg til en historievitenskapelig lidenskap. Når temaet for masteroppgaven skulle velges føltes det naturlig å ta tak i nettopp denne interessen. Mitt mål med oppgaven er å oppnå en bedre forståelse for forskningsfeltet og historiefagets påvirkning på fortid og samtid. Jeg ønsker å rette en stor takk til min veileder, professor Knut Kjeldstadli, for all god hjelp og støtte. Hans bistand og bokhylle har vært uvurderlig fra start til slutt! En langstrakt takk til Rune Blix Hagen. Siden min første dag ved universitetet i Tromsø, har han fostret begeistringen min og veiledet meg gjennom bachelorgraden som ligger til grunn for dette prosjektet. Takk til Varanger Museum og spesielt Synnøve F. Eikevik. Deres bidrag har vært uunnværlig for gjennomføringen av prosjektet. Takk til lærere og elever ved Vardø skole og VGS. Tusen takk til familie og venner for støtten i gjennom studieløpet. -

Women Directors in 'Global' Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism And

Women Directors in ‘Global’ Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism and Representation Despoina Mantziari PhD Thesis University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies March 2014 “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Women Directors in Global Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism and Aesthetics The thesis explores the cultural field of global art cinema as a potential space for the inscription of female authorship and feminist issues. Despite their active involvement in filmmaking, traditionally women directors have not been centralised in scholarship on art cinema. Filmmakers such as Germaine Dulac, Agnès Varda and Sally Potter, for instance, have produced significant cinematic oeuvres but due to the field's continuing phallocentricity, they have not enjoyed the critical acclaim of their male peers. Feminist scholarship has focused mainly on the study of Hollywood and although some scholars have foregrounded the work of female filmmakers in non-Hollywood contexts, the relationship between art cinema and women filmmakers has not been adequately explored. The thesis addresses this gap by focusing on art cinema. It argues that art cinema maintains a precarious balance between two contradictory positions; as a route into filmmaking for women directors allowing for political expressivity, with its emphasis on artistic freedom which creates a space for non-dominant and potentially subversive representations and themes, and as another hostile universe given its more elitist and auteurist orientation. -

The Austere Cinema Of

'SAtti:4110--*. Control and Redemption The Austere Cinema of The Bresson Project is one of the most Jean—Luc Godard says, "Robert Bresson is comprehensive retrospectives undertaken by French cinema, as Dostoevsky is the Russian Cinematheque Ontario. Robert Bresson, now novel and Mozart German music." Yet few of in his early 90s, is described by many critics as Bresson's films are available in any form in the world's greatest living filmmaker. Starting North America and little has been written on with what he considers to be his first film, Les him in English. Accompanying the new series Anges du peche in 1943, Bresson made 13 of 35mm prints by Cinematheque Ontario feature—length films in 40 years. (An earlier for The Bresson Project, is Robert Bresson, a comedy, Les Affaires publiques, filmed in 1935, 600—page collection of essays in English from was considered lost until its discovery in 1987 writer/critics such as Andre Bazin, Susan at La Cinematheque Francaise.) Although Sontag, Alberto Moravia, Jonathan Rosenbaum perhaps not as prodigious as the output from and Rene Predal. Following its debut showing other directors, Bresson's body of work, with at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto last fall, all its passionate austerity, has had an The Bresson Project travels to more than an inestimable influence on the history of cinema. dozen centres across North America this year. T ravelling across central France this route more times than I can recall, toward Lyon, as you near Bromont- more often than not on the way to Lamothe, the spare hillside village Robert the Cannes Film Festival. -

The Story Is Memory: Antonio Bibalos Glassmenagerie

The story is memory: Antonio Bibalos Glassmenagerie. En studie i tradisjon og sjanger i nyere norsk musikkdramatikk. Eli Engstad Risa Hovedoppgave i musikkvitenskap Våren 2005 Universitetet i Oslo Innhold Forord ………………………………………………………………………………....3 Innledning …………………………………………………………………………….4 Kapittel 1: Nyere norsk musikkdramatikk …………………………………...11 1.1. Norsk musikkdramatikk etter 1945 ……………………………...12 1.1.1. Profesjonelle scener for samtidsopera i Norge …………...16 1.1.2. Den nye musikkdramatikken ved Den Norske Opera ……20 1.2. Begrepet om det nye ……………………………………...............22 1.3. Operadiskurs i Norge ……………………………………………...25 Kapittel 2: Forholdet til tradisjonen …………………………………………..29 2.1. Opera og tradisjonsbegrep ……………………………………….30 2.1.1. Tradisjonsbegrep …………………………………………….32 2.1.2. Forholdet til tradisjonen ……………………………………..34 2.1.3. Brudd med tradisjonen ………………………………………36 2.2. Tradisjonalismen i norsk opera ………………………………….39 2.2.1. Tradisjonsbrudd i norsk musikkdramatikk …………………43 Kapittel 3: Sjangerproblemet …………………………………………………..45 3.1. Tilnærming til sjangerstudier …………………………………….49 3.1.1. Hybriden ………………………………………………………53 3.1.2. Det operatiske ………………………………………………..54 3.2. Postludium …………………………………………………………..58 Kapittel 4: The Glassmenagerie ……………………………………………….61 4.1. Litteraturoperabegrepet …………………………………………..61 4.1.1. Presentasjon av problemstillinger for analysen …………..65 4.2. Operaens handling …………………………………………………68 4.3. Memory play……………………………………………….………...72 4.3.1. Besetning og instrumentasjon ……………………………...73 4.4. Tidsproblemet ……………………………………………………....77 -

Raining Stones Raining Stones

HOMMAGE RAINING STONES RAINING STONES Ken Loach Um seiner Tochter ein Kleid zur Erstkommunion kaufen zu können, Großbritannien 1993 nimmt der arbeitslose Bob jeden Gelegenheitsjob an. Als ihm während 90 Min. · DCP · Farbe des Verkaufs von selbst erjagtem Hammelfleisch der Lieferwagen ge- stohlen wird, bleibt ihm ohnehin keine Wahl: Er reinigt Kloaken, wird Regie Ken Loach als Rausschmeißer schon am ersten Arbeitstag in der Disco verprügelt Buch Jim Allen Kamera Barry Ackroyd und beteiligt sich schließlich gemeinsam mit seinem Kumpel Tommy Schnitt Jonathan Morris an einem Diebstahl von Rasensoden aus dem Klub der Konservativen. Musik Stewart Copeland of SixteenCourtesy Films Wirklich ernst wird Bobs Lage allerdings, als ein Schuldschein in den Mischung Kevin Brazier Besitz des Kredithais Tansey gerät und der brutale Gangster Bobs Frau “Es geht um Menschen, die niedergeknüppelt, Ton Ray Beckett aber nicht gebrochen werden. Das und Tochter gewaltsam bedrängt … Geschickt verbindet RAINING Production Design Martin Johnson Entscheidende an Bob ist, dass er nicht STONES – nach einem Drehbuch von Jim Allen (1926–1999), der selbst Art Director Fergus Clegg untergeht und verzweifelt versucht, seine viele Jahre lang in Middlestone bei Manchester lebte – die Darstellung Kostüm Anne Sinclair Selbstachtung zu bewahren. Außerdem der regionalen wirtschaftlichen Krise unter der Regierung Thatcher mit Maske Louise Fisher behandelt der Film verschiedene Arten von Thriller-Elementen. Dabei lässt Ken Loach (neben burlesken Extempo- Produzentin Sally Hibbin Moral. Es ist nichts Falsches daran, auf dem res) an authentischen Schauplätzen wie einem Nachbarschaftsverein Darsteller Moor ein Schaf zu klauen und es an einen immer wieder Hinweise auf prekäre Wohnsituationen, die ausweglose Metzger zu verkaufen oder Rasensoden von Bruce Jones (Bob Williams) Lage arbeitsloser Jugendlicher und die enge Verbindung von Armut, Julie Brown (Anne Willams) der Rasenbowling-Bahn der Konservativen Verschuldung und Gewalt einfließen. -

Robert Bresson: Pickpocket Besetzung: Michel: Martin Lassalle

Robert Bresson: Pickpocket Besetzung: Michel: Martin Lassalle Jeanne: Marika Green Jacques: Pierre Leymarie Inspector: Jean Pelegri Thief: Kassagi Michel's mother: Dolly Scal Regie: Robert Bresson Buch: Robert Bresson Kamera: L.H.Burel Inhalt : Paris. Michel ist der Ansicht, dass es bestimmten Menschen erlaubt ist zu stehlen um sich am Leben zu halten und zu entfalten. So treibt ihn sein Hochmut dazu Taschendieb zu werden. Diese Ansicht vertritt er auch vor einem Kommissar, der wiederum ihm klarmachen will, das man irgendwann ihn dieser Welt des Stehlens gefangen ist. Zudem hält ihn sein Verhalten von Jeanne fern, zu der er sich hingezogen fühlt. Als seine Komplizen gefasst werden flieht er aus Paris. Zwei Jahre später kehrt er zurück. Von nun an möchte er Jeanne, die mittlerweile ein Kind hat helfen und arbeitet. Doch schließlich kann er der Versuchung nicht widerstehen und klaut erneut. Dabei wird er jedoch überführt. Im Gefängnis kommt ihm schließlich die Erkenntnis, dass Jeanne seine Rettung ist und entfaltet die Liebe zu ihr. Robert Bresson (1901- 1999) Filmographie: Les Affaires publiques (1934) Les Anges du péché (1943) Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945) Journal d'un curé de campagne (1950) Un condamné à mort s'est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut (1956) . Pickpocket (1959) Le Procès de Jeanne d'Arc (1962) Au hasard Balthazar (1966) Mouchette (1967) Une femme douce (1969) Quatre nuits d'un rêveur (1971) Lancelot du Lac (1974) Le Diable probablement (1977) L'Argent (1983) Bresson bringt schon früh seinen eigenen Stil in seine Filme. Karge Bilder, immer nah an der Figur.