Dear Rene Romo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3Rd Quarter 2017

Stagecoach Property Owners Association Stagecoach Express A Quarterly Newsletter www.Stage-Coach.com № 3rd Quarter • 2017 President’s Message Meet the Association’s New Membership Survey 2017 Property Valuations Stagecoach Real Estate Board Members on Potential Covenant Activity Amendments Page 1-2 Page 2 Page 3-4 Page 5 Page 6 Out with the old, in with the Wildfire Mitigation - Now Common Area Trail Construction Board Meeting Minutes new... you see it, now you don’t... Improvements... Continues... May 13, 2017 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 13-19 Board Meeting Minutes July 1, 2017 Page 20-26 While there are still many unknowns, this is a critical issue for all members of the Association. The Board and the President’s Association’s legal counsel are closely monitoring events and communications on this issue and we have been in contact Message with the State, County and district officials regarding our concerns. By John Troka You can find more information about this issue on our website at www.Stage-coach.com. We will also post additional information and updates on the website as appropriate. I As fall begins in Stagecoach, we look forward to the encourage each of you to actively engage in understanding changing colors and cooler, and hopefully, wetter days ahead. and participate with the Association in seeking a positive Unfortunately this year the change in seasons may also bring resolution of this matter with it a significant challenge for our members whose lots are In other Association news, the Association’s annual not currently served by the centralized water and sanitation membership meeting was held in July. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Fort Bowie U.S

National Park Service Fort Bowie U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Bowie National Historic Site The Chiricahua Apaches Introduction The origin of the name "Apache" probably stems from the Zuni "apachu". Apaches in fact referred to themselves with variants of "nde", simply meaning "the people". By 1850, Apache culture was a blend of influences from the peoples of the Great Plains, Great Basin, and the Southwest, particularly the Pueblos, and as time progressed—Spanish, Mexican, and the recently arriving American settler. The Apache Tribes Chiricahua speak an Athabaskan language, relating Geronimo was a member of the Bedonkohe, who them to tribes of western Canada. Migration from were closely related to the Chihenne (sometimes this region brought them to the southern plains by referred to as the Mimbres); famous leaders of the 1300, and into areas of the present-day American band included Mangas Coloradas and Victorio. Southwest and northwestern Mexico by 1500. This The Nehdni primarily dwelled in northern migration coincided with a northward thrust of Mexico under the leadership of Tuh. the Spanish into the Rio Grande and San Pedro Valleys. Cochise was a Chokonen Chiricahua leader who rose to leadership around 1856. The Chockonen Chiricahuas of southern Arizona and New primarily resided in the area of Apache Pass and Mexico were further subdivided into four bands: the Dragoon Mountains to the west. Bedonkohe, Chokonen, Chihenne, and Nehdni. Their total population ranged from 1,000 to 1,500 people. Organization and Apache population was thinly spread, scattered of Apache government and was the position that Family Life into small groups across large territories, tribal chiefs such as Cochise held. -

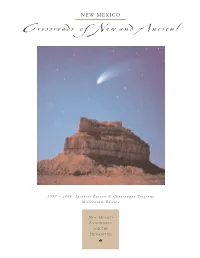

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century

Hannigan 1 “Overrun All This Country…” Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century “José Francisco Chavez.” Library of Congress website, “General Nicolás Pino.” Photograph published in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, The History of the Military July 15 2010, https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/congress/chaves.html Occupation of the Territory of New Mexico, 1909. accessed March 16, 2018. Isabel Hannigan Candidate for Honors in History at Oberlin College Advisor: Professor Tamika Nunley April 20, 2018 Hannigan 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2 I. “A populace of soldiers”, 1819 - 1848. ............................................................................................... 10 II. “May the old laws remain in force”, 1848-1860. ............................................................................... 22 III. “[New Mexico] desires to be left alone,” 1860-1862. ...................................................................... 31 IV. “Fighting with the ancient enemy,” 1862-1865. ............................................................................... 53 V. “The utmost efforts…[to] stamp me as anti-American,” 1865 - 1904. ............................................. 59 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 72 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

42 New Mexico //May 2017

The Wild Heart of the Gila 42 NEW MEXICO // MAY 2017 Geronimo Trail Guest Ranch gives dudes (and dudettes!) a way into the history of the very Old West. by WILL GRANT photos by GABRIELLA MARKS HIRTEEN MILES NORTH of Truth or Consequences, exit 89 on Interstate 25 is a lonely, windy place. The landscape is devoid of trees. Elephant Butte Reservoir, the largest in the state at 40 miles long, sits to the east, so dwarfed by the knobby Fra Cristóbal Range that it looks like a puddle in a sandbox. To the west, the faint blue profile of the Gila country sits low to the horizon, barely a suggestion of its three million acres of wilderness. And that’s where I’m headed—the Tlargest patch of wildland in the lower 48. Call us when you leave the interstate so we know when to expect you, wrote my hosts, Seth and Meris Stout, owners of the Geronimo Trail Guest Ranch, in an email the previous week. The message was laden with caution- ary advice—a dearth of GPS or cellular service, the dangers of washboard dirt roads, open range for cattle grazing, wildlife everywhere. They advised against making the two-hour drive from the interstate at night and, in a bold font, said to bring along a printed copy of the directions. Parked at exit 89, I feel a little like I’m calling my parents. But the call is brief and painless. I hang up with Meris and start west toward a serrated ridgeline in the far distance. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 87 Number 3 Article 4 7-1-2012 Boots on the Ground: A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley James Blackshear Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Blackshear, James. "Boots on the Ground: A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley." New Mexico Historical Review 87, 3 (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol87/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Boots on the Ground a history of fort bascom in the canadian river valley James Blackshear n 1863 the Union Army in New Mexico Territory, prompted by fears of a Isecond Rebel invasion from Texas and its desire to check incursions by southern Plains Indians, built Fort Bascom on the south bank of the Canadian River. The U.S. Army placed the fort about eleven miles north of present-day Tucumcari, New Mexico, a day’s ride from the western edge of the Llano Estacado (see map 1). Fort Bascom operated as a permanent post from 1863 to 1870. From late 1870 through most of 1874, it functioned as an extension of Fort Union, and served as a base of operations for patrols in New Mexico and expeditions into Texas. Fort Bascom has garnered little scholarly interest despite its historical signifi cance. -

Major Gifts Help Cather Group Secure Grant on Saturday, Made the Conference Unique in the History of the Hastings Tribune, Aug

"The Cather Foundation’s success in meeting the NEH Endowment Challenge marks a new stage in our evolution as a society," said Charles Peek of Kearney, President of the Foundation Board of Governors. With the grant money in hand, the Foundation now has an endowment of $1.1 million for the Opera House. Interest revenue will be used to support cultural and educational programming, provide some money for a part-time archivist, and help maintain the building. Fundraising for the endowment challenge began even before the 1885 Opera House reopened to the public in May 2003 following a $1.68 million renovation. In fact, about $300,000 already had been raised by the time of the grand reopening. Originally, the Foundation had faced a deadline of July 2004 to finish its fundraising for the match. That deadline was extended twice. "[NEH] went out on a limb for us," said Betty Kort, Foundation Executive Director. "We understand that they have never extended a significant NEH Challenge Grant to so small an organization as the Cather Foundation. It is difficult for (Continued on page 10) The 2006 Willa Cather Spring Conference focused on Willa Cather’s French Connections and featured the novel Shadows on the Rock. The Scholars’ Symposium, a new feature of the Conference, necessitated a third day. This, along with Photograph by Dee Yost. the dedication of the newly acquired Willa Cather Memorial Prairie and the international ambiance of the traditional events Major Gifts Help Cather Group Secure Grant on Saturday, made the Conference unique in the history of the Hastings Tribune, Aug. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

Hell on Wheels

MercantileEXCITINGSee section our NovemberNovemberNovember 2001 2001 2001 CowboyCowboyCowboy ChronicleChronicleChronicle(starting on PagepagePagePage 90) 111 The Cowboy Chronicle~ The Monthly Journal of the Single Action Shooting Society ® Vol. 21 No. 11 © Single Action Shooting Society, Inc. November 2008 . HELL ON WHEELS . THE SASS HIGH PLAINS REGIONAL By Captain George Baylor, SASS Life #24287 heyenne, Wyoming – The HIGHLIGHTS on pages 70-73 very name conjures up images of the Old West. chief surveyor for the Union Pacific C Wyoming is a very big state Railroad, surveyed a town site at with very few people in it. It has what would become Cheyenne, only 500,000 people in the entire Wyoming. He called it Cow Creek state, but about twice as many ante- Crossing. His friends, however, lope. A lady at Fort Laramie told me thought it would sound better as Cheyenne was nice “if you like big Cheyenne. Within days, speculators cities.” Cheyenne has 55,000 people. had bought lots for a $150 and sold A considerable amount of history them for $1500, and Hell on Wheels happened in Wyoming. For example, came over from Julesburg, Colorado— Fort Laramie was the resupply point the previous Hell on Wheels town. for travelers going west, settlers, and Soon, Cheyenne had a government, the army fighting the Indian wars. but not much law. A vigilance com- On the far west side of the state, mittee was formed and banishments, Buffalo Bill built his dream town in even lynchings, tamed the lawless- Cody, Wyoming. ness of the town to some extent. Cheyenne, in a way, really got its The railroad was always the cen- start when the South seceded from tral point of Cheyenne.