Fringed Myotis Myotis Thysanodes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter Number 29 November 2007 ABS Website: http://abs.ausbats.org.au ABS Listserver: http://listserv.csu.edu.au/mailman/listinfo/abs ISSN 1448-5877 The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 29, November 2007 – Instructions for contributors – The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter will accept contributions under one of the following two sections: Research Papers, and all other articles or notes. There are two deadlines each year: 31st March for the April issue, and 31st October for the November issue. The Editor reserves the right to hold over contributions for subsequent issues of the Newsletter, and meeting the deadline is not a guarantee of immediate publication. Opinions expressed in contributions to the Newsletter are the responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australasian Bat Society, its Executive or members. For consistency, the following guidelines should be followed: • Emailed electronic copy of manuscripts or articles, sent as an attachment, is the preferred method of submission. Manuscripts can also be sent on 3½” floppy disk, preferably in IBM format. Please use the Microsoft Word template if you can (available from the editor). Faxed and hard copy manuscripts will be accepted but reluctantly! Please send all submissions to the Newsletter Editor at the email or postal address below. • Electronic copy should be in 11 point Arial font, left and right justified with 16 mm left and right margins. Please use Microsoft Word; any version is acceptable. • Manuscripts should be submitted in clear, concise English and free from typographical and spelling errors. Please leave two spaces after each sentence. -

Species Assessment for Fringed Myotis (Myotis Thysanodes ) in Wyoming

SPECIES ASSESSMENT FOR FRINGED MYOTIS (MYOTIS THYSANODES ) IN WYOMING prepared by DOUGLAS A. KEINATH Zoology Program Manager, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave, Dept. 3381, Laramie, Wyoming 82071; 307-766-3013; [email protected] prepared for United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office Cheyenne, Wyoming December 2003 Keinath - Myotis thysanodes December 2003 Table of Contents SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 3 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................................... 5 Morphological Description ...................................................................................................... 5 Taxonomy and Distribution ..................................................................................................... 6 Taxonomy .......................................................................................................................................6 Range...............................................................................................................................................7 Abundance.......................................................................................................................................8 -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Chiropterology Division BC Arizona Trial Event 1 1. DESCRIPTION: Participants Will Be Assessed on Their Knowledge of Bats, With

Chiropterology Division BC Arizona Trial Event 1. DESCRIPTION: Participants will be assessed on their knowledge of bats, with an emphasis on North American Bats, South American Microbats, and African MegaBats. A TEAM OF UP TO: 2 APPROXIMATE TIME: 50 minutes 2. EVENT PARAMETERS: a. Each team may bring one 2” or smaller three-ring binder, as measured by the interior diameter of the rings, containing information in any form and from any source. Sheet protectors, lamination, tabs and labels are permitted in the binder. b. If the event features a rotation through a series of stations where the participants interact with samples, specimens or displays; no material may be removed from the binder throughout the event. c. In addition to the binder, each team may bring one unmodified and unannotated copy of either the National Bat List or an Official State Bat list which does not have to be secured in the binder. 3. THE COMPETITION: a. The competition may be run as timed stations and/or as timed slides/PowerPoint presentation. b. Specimens/Pictures will be lettered or numbered at each station. The event may include preserved specimens, skeletal material, and slides or pictures of specimens. c. Each team will be given an answer sheet on which they will record answers to each question. d. No more than 50% of the competition will require giving common or scientific names. e. Participants should be able to do a basic identification to the level indicated on the Official List. States may have a modified or regional list. See your state website. -

Anatomical Diversification of a Skeletal Novelty in Bat Feet

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.13786 Anatomical diversification of a skeletal novelty in bat feet Kathryn E. Stanchak,1,2 Jessica H. Arbour,1 and Sharlene E. Santana1 1Department of Biology and Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 2E-mail: [email protected] Received December 21, 2018 Accepted May 18, 2019 Neomorphic, membrane-associated skeletal rods are found in disparate vertebrate lineages, but their evolution is poorly under- stood. Here we show that one of these elements—the calcar of bats (Chiroptera)—is a skeletal novelty that has anatomically diversified. Comparisons of evolutionary models of calcar length and corresponding disparity-through-time analyses indicate that the calcar diversified early in the evolutionary history of Chiroptera, as bats phylogenetically diversified after evolving the capac- ity for flight. This interspecific variation in calcar length and its relative proportion to tibia and forearm length is of functional relevance to flight-related behaviors. We also find that the calcar varies in its tissue composition among bats, which might affect its response to mechanical loading. We confirm the presence of a synovial joint at the articulation between the calcar and the cal- caneus in some species, which suggests the calcar has a kinematic functional role. Collectively, this functionally relevant variation suggests that adaptive advantages provided by the calcar led to its anatomical diversification. Our results demonstrate that novel skeletal additions can become integrated into vertebrate body plans and subsequently evolve into a variety of forms, potentially impacting clade diversification by expanding the available morphological space into which organisms can evolve. -

Characterizing Summer Roosts of Male Little Brown Myotis (Myotis Lucifugus)

CHARACTERIZING SUMMER ROOSTS OF MALE LITTLE BROWN MYOTIS (MYOTIS LUCIFUGUS) IN LODGEPOLE PINE-DOMINATED FORESTS by Shannon Lauree Hilty A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Fish and Wildlife Management MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana May 2020 ©COPYRIGHT by Shannon Lauree Hilty 2020 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my mentors, Andrea Litt, Bryce Maxell, Lauri Hanauska- Brown, and Amie Shovlain, as well as my committee members Claire Gower and Robert Garrott, for guiding me through this process. Andrea, thank you for providing direction through the Spartan course that is graduate school and for introducing me to my lab family. Bryce, Amie, and Lauri, thank you for being some of the biggest cheerleaders for Montana’s smallest wildlife groups. Thank you to everyone that helped me in the field, including Brandi Skone, Heather Harris, Cody Rose Brown, Erin Brekstad, Kathi and Hazel Irvine, Wilson and Jane Wright, Katie Carroll, Michael Yarnall, Michael Forzley, Autumn Saunders, Katie Geraci, Rebecca Hamlin-Sharpe, Devin Jones, Olivia Bates, Emma Grusing, and my primary technicians, Jacob Melhuish, Scott Hollis, and Monique Metza. I am grateful to my current employer, Westech Environmental Services. You are a phenomenal group of people, and I am so happy to call you family. I want to thank Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, Montana Natural Heritage Program, USDA Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and MPG Ranch for providing funding for this project. I am especially thankful to Alexis McEwan, Boaz Crees, Scott Blum, Dan Bachen, Braden Burkholder, and Karen Coleman for offering expertise, gear, and logistical support to my field team. -

Hammerson-Bat-Conservation-2017.Pdf

Biological Conservation 212 (2017) 144–152 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Strong geographic and temporal patterns in conservation status of North MARK American bats ⁎ G.A. Hammersona, M. Klingb, M. Harknessc, M. Ormesd, B.E. Younge, a NatureServe, Port Townsend, WA 98368, USA b Dept. of Integrative Biology, 3040 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3140, USA c NatureServe, 2108 55th St., Suite 220, Boulder, CO 80301, USA d NatureServe, University of Massachusetts, c/o Biology Department, 100 Morrissey Boulevard, Boston, MA 02125-3393, USA e NatureServe, Escazu, Costa Rica ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Conservationists are increasingly concerned about North American bats due to the arrival and spread of the Bats White-nose Syndrome (WNS) disease and mortality associated with wind turbine strikes. To place these novel Conservation status threats in context for a group of mammals that provides important ecosystem services, we performed the first Disease comprehensive conservation status assessment focusing exclusively on the 45 species occurring in North America Geographic patterns north of Mexico. Although most North American bats have large range sizes and large populations, as of 2015, Wind energy 18–31% of the species were at risk (categorized as having vulnerable, imperiled, or critically imperiled NatureServe conservation statuses) and therefore among the most imperiled terrestrial vertebrates on the con- tinent. Species richness is greatest in the Southwest, but at-risk species were more concentrated in the East, and northern faunas had the highest proportion of at-risk species. Most ecological traits considered, including those characterizing body size, roosting habits, migratory behavior, range size, home range size, population density, and tendency to hibernate, were not strongly associated with conservation status. -

Table of Contents

XIII. SPECIES ACCOUNTS The majority of the following species accounts were originally written by various members of the Western Bat Working Group in preparation for the WBWG workshop in Reno, Nevada, February 9-18, 1998. They have been reviewed and updated by various members of the Colorado Bat Working Group for the 2018 revision of the Colorado Bat Conservation Plan. Several species accounts were newly developed for the second edition of the plan and authorship reflects this difference. The status of Colorado bat species as ranked by NatureServe and the Colorado Natural Heritage Program (NatureServ/CNHP), The Colorado Parks and Wildlife State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) rankings and state threatened and endangered list, Colorado Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Region 2 of the US Forest Service (USFS), and the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) as of December 2017 is included in each species account. Conservation status of bat species, as defined by NatureServe, is ranked on a scale of 1–5 as follows: critically imperiled (G1), imperiled (G2), vulnerable (G3), apparently secure (G4), and demonstrably secure (G5). Assessment and documentation of status occurs at 3 geographic scales: global (G), national (N), and state/province (S). The CPW State Wildlife Action Plan ranks include Tier 1 for species of highest conservation priority and Tier 2 for species whose listing status is of concern but the urgency of action is deemed to be less. BLM and USFS rankings are given for sensitive species (SS) only as no threatened or endangered bat species currently exist in their management boundaries. Colorado Bat Conservation Plan 3/28/2018 Western Bat Working Group, Colorado Committee Page 126 of 204 ALLEN’S BIG-EARED BAT (IDIONYCTERIS PHYLLOTIS) Prepared by Michael J. -

Appendix J Wildlife Reports

Appendix J Wildlife Reports To: Linda Cope, Wyoming Game and Fish Department From: Kim Chapman & Genesis Mickel, Applied Ecological Services Date: June 14, 2017 Re: Memo on new surveys requested by Wyoming Game & Fish Department _____________________________________________________________________________________ AES biologists have been collecting baseline biological data and recording incidental observations for the Boswell Springs Wind Project between 2011 and 2016 in consultation with Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). During a Project meeting on May 26, 2017 and follow-up letter dated June 5, 2017, staff at the WGFD requested targeted surveys for four species of interest to better assess their presence or absence in the Project area. The four species are black-footed ferret, swift fox, mountain plover, and long-billed curlew. The purpose of this memo is to summarize the survey methodology presented and accepted by WGFD on a June 12, 2017 conference call. 1. White-tailed prairie dog activity areas. Incidental sightings or evidence for black-footed ferret, swift fox, and mountain plover, have been isolated to areas identified as high-density for prairie dog burrows. As a result, the first task is to refine the mapping of the prairie dog colonies and field verify the high- activity areas. The resulting high-activity areas will then be used to survey for presence or absence of these species. Prairie dog burrow densities were originally mapped in the Project area from aerial photos, which were then ground-truthed along transects. The resulting map indicated areas of burrows at high, moderate, and low densities, but did not pinpoint the areas where prairie dogs were most active. -

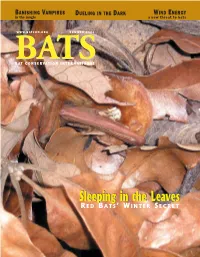

Sleeping in the Leaves

BANISHING VAMPIRES DUELING IN THE DARK WIND ENERGY in the jungle a new threat to bats WWW.BATCON.ORG SUMMER 2004 BATSBAT CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL SleepingSleeping inin thethe LeavesLeaves R ED B ATS’ WINTER S ECRET Vo lume 22, No. 2, Summer 2004 BATS P.O. Box 162603, Austin, Texas 78716 (512) 327-9721 • Fax (512) 327-9724 Publications Staff D i rector of Publications: Robert Locke Photo Editor: Kristin Hay FEATURES Copyeditors: Angela England, Valerie Locke B AT S welcomes queries from writers. Send your article proposal with a brief outline and a description of any photos to the address 1 Banishing the Vampires of the Jungle above or via e-mail to: [email protected]. A remote village finds a new appreciation for bats M e m b e r s : Please send changes of address and all correspondence by Sandra Peters to the address above or via e-mail to [email protected]. Please include your label, if possible, and allow six weeks for the change 4 Wind Energy & the Threat to Bats of address. BCI, industry and government join to resolve a new danger facing Founder & Pre s i d e n t : Dr. Merlin D. Tuttle Associate Executive Director: Elaine Acker A m e r i c a ’s bats B o a rd of Tru s t e e s : Andrew Sansom, Chair by Merlin D. Tuttle John D. Mitchell, Vice Chair Verne R. Read, Chairman Emeritus 6 Hibernation: Red Bats do it in the Dirt Peggy Phillips, Secretary Elizabeth Ames Jones, Treasurer by Brad Mormann, Miranda Milam and Lynn Robbins Jeff Acopian; Mark A. -

Terrestrial Mammal Species of Special Concern in California, Bolster, B.C., Ed., 1998 54

Terrestrial Mammal Species of Special Concern in California, Bolster, B.C., Ed., 1998 54 Fringed myotis, Myotis thysanodes Elizabeth D. Pierson & William E. Rainey Description: Myotis thysanodes is one of the larger Myotis species, with a forearm length of 40-47 mm, and an adult weight of 5.3-7.6 g. It can be distinguished from all other California bat species by a well-developed fringe of hair on the posterior edge of the tail membrane. It has relatively large ears, and can most readily be confused with the long-eared myotis, Myotis evotis. M. evotis is smaller (forearm = 36-41 mm), with longer ears (22-25 mm in M. evotis vs. 16-20 mm in M. thysanodes). Although M. evotis sometimes has a scant fringe of hairs on its tail membrane, it is never as distinct as that in M. thysanodes. M. thysanodes varies in color from yellowish brown to a cinnamon brown, with more northern populations tending to have darker coloration. Taxonomic Remarks: M. thysanodes is in the Family Vespertilionidae. The type locality for M. thysanodes is Old Fort Tejon (at Tejon Pass) in the Tehachapi Mountains, Kern County, California (Miller 1897). Four subspecies are recognized (Hall 1981, Manning and Jones 1988), M. t. aztecus, M. t. thysanodes, M. t. pahasapensis, and M. t. vespertinus. Most M. thysanodes in California are referable to M. t. thysanodes; populations in the northwestern part of the state (Humboldt, Siskiyou and Shasta counties) have recently been placed in the new subspecies, M. t. vespertinus (Manning and Jones 1988), although relatively few specimens have been examined and the boundary between subspecies has not been clearly delineated. -

Region 1 Acoustic Bat Inventory: National Wildlife Refuges in Eastern Oregon, Eastern Washington, and Idaho

Region 1 Acoustic Bat Inventory: National Wildlife Refuges in Eastern Oregon, Eastern Washington, and Idaho BY Jenny K. Barnett Zone Inventory and Monitoring Biologist US Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Region Portland, OR September 2014 INTRODUCTION Bats are an important species group, comprising almost one-fifth of all land mammal species world- wide. They provide important ecological services by consuming large quantities of nocturnal insects, many of which are forest and crop pests (Boyles et al. 2011). They also face unprecedented threats from numerous factors, including wind power development, habitat loss, climate change, and the novel disease White-nose Syndrome (Rodhouse et al. 2012). However, they are difficult to monitor due to their nocturnal habits and secretive nature (Rodhouse et al. 2012; Manley et al. 2006). There have been recent calls for increased monitoring of bat populations by several land management agencies (Manley et al 2006; Rainey et al. 2009; Bucci et al. 2010), for large-scale monitoring of bat populations status and trend (Rodhouse et al. 2012), and for gathering baseline data on activity patterns of western bats before White-nose Syndrome arrives in the region (Schwab and Mabee 2014). Bats are under-surveyed species on National Wildlife Refuges (refuges). A total of 8 east of the Cascade Mountains in Region 1 identified a need for bat inventories in the objectives of their Comprehensive Conservation Plans (CCP). Yet, few refuges had surveyed for bats although they were included as potential species on refuge species lists based on range maps. No information on rates of bat activity or species composition of the bat community was available.