Football Academy Model in South Africa. Mark Mcilroy 296212

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And YOU Will Be Paying for It Keeping the Lights On

AFRICA’S BEST READ October 11 to 17 2019 Vol 35 No 41 mg.co.za @mailandguardian Ernest How rugby After 35 Mancoba’s just can’t years, Africa genius give has a new acknowledged racism tallest at last the boot building Pages 40 to 42 Sport Pages 18 & 19 Keeping the lights on Eskom burns billions for coal And YOU will be paying for it Page 3 Photo: Paul Botes Zille, Trollip lead as MIGRATION DA continues to O Visa row in Vietnam Page 11 OSA system is ‘xenophobic’ Page 15 tear itself apart OAchille Mbembe: No African is a foreigner Pages 4 & 5 in Africa – except in SA Pages 28 & 29 2 Mail & Guardian October 11 to 17 2019 IN BRIEF ppmm Turkey attacks 409.95As of August this is the level of carbon Kurds after Trump Yvonne Chaka Chaka reneges on deal NUMBERS OF THE WEEK dioxide in the atmosphere. A safe number Days after the The number of years Yvonne Chaka is 350 while 450 is catastrophic United States Chaka has been married to her Data source: NASA withdrew troops husband Dr Mandlalele Mhinga. from the Syria The legendary singer celebrated the border, Turkey Coal is king – of started a ground and couple's wedding anniversary this aerial assault on Kurdish week, posting about it on Instagram corruption positions. Civilians were forced to fl ee the onslaught. President Donald Trump’s unex- Nigeria's30 draft budget plan At least one person dies every single day so pected decision to abandon the United States’s that we can have electricity in South Africa. -

Sudáfrica México

LA PRENSA GRÁFICA VIERNES 11 DE JUNIO DE 2010 LA TRIBUNA 8 www.laprensagrafica.com SUDÁFRICA PLANTILLA EL TÉCNICO NOMBRE POSICIÓN GRUPO A 1 Itumeleng Khune Arquero CARLOS PARREIRA 2 Moeneeb Josephs Arquero FECHA DE NACIMIENTO: 27 DE ABRIL DE 1947 3 Shu-Aib Walters Arquero LUGAR DE NACIMIENTO: 4 Matthew Booth Defensa RÍO DE JANEIRO, BRASIL 5 Siboniso Gaxa Defensa TRAYECTORIA: 6 Bongani Khumalo Defensa AL DIRIGIR A SUDÁFRICA EN EL MUNDIAL DE 2010, PARREIRA 7 Tsepo Masilela Defensa IGUALARÁ AL SERBIO BORA 8 Aaron Mokoena Defensa MILUTINOVIC COMO LOS 9 Anele Ngcongca Defensa AQUÍ DOS ENTRENADORES CON MÁS 10 Siyabonga Sangweni Defensa PARTICIPACIONES EN MUNDIALES, 11 Lucas Thwala Defensa CON SEIS EDICIONES CADA UNO. 12 Lance Davids Mediocampista 13 Kagisho Dikgacoi Mediocampista LA LISTA DEL ANFITRIÓN 14 Thanduyise Khuboni Mediocampista Sudáfrica espera tener su mejor participación en 15 Reneilwe Letsholonyane Mediocampista TENDRÁN una Copa del Mundo amparada en sus jugadores 16 Teko Modise Mediocampista con experiencia europea. Pese a que Carlos Parreira 17 Surprise Moriri Mediocampista dejó fuera de la lista a Benny McCarthy por sus 18 Steven Pienaar Mediocampista 19 Siphiwe Tshabalala Mediocampista problemas físicos, esta tiene otros jugadores con 20 Macbeth Sibaya Mediocampista experiencia europea, donde el principal referente 21 Katlego Mphela Delantero ahora es Steven Pienaar, quien jugó para el Ajax 22 Siyabonga Nomvete Delantero FRACASO 23 Bernaard Parker Delantero de Holanda, y hoy participa en la Premier League. Dos ex campeones del mundo, Uruguay y ASOC. DE FÚTBOL DE SUDÁFRICA PALMARÉS EN LA COPA MUNDIAL PAÍS: SUDÁFRICA GANADOR: 0 CONTINENTE: ÁFRICA SEGUNDO: 0 Francia, contra el anfitrión del torneo, ABREVIATURA FIFA: RSA PARTICIPACIONES EN LA COPA AÑO DE FUNDACIÓN: 1932 MUNDIAL DE LA FIFA: AFILIADO DESDE: 1932 2 (1998, 2002) Sudáfrica, y como invitado de cierre una de las CONFEDERACIÓN: CAF NOMBRE: STEVEN PIENAAR HISTORIAL: Pienaar será el potencias de CONCACAF, México. -

An Investigation of Best Practices in Youth Development Programmes at Selected Football Academies in the Western Cape

An Investigation of Best Practices in Youth Development Programmes at Selected Football Academies in the Western Cape. By Ashley Ian Jacobs 2444431 A full thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the Degree MAGISTER ARTIUM SPORT, RECREATION AND EXERCISE SCIENCE in the Department of Sport, Recreation and Exercise Science in the Faculty of Community and Health Sciences at the UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE Supervisor: Dr. Simone Titus October 2020 http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ Abstract Football around the globe has been used as a vehicle for youth development initiatives. Youth development programmes foster social change in communities and provide an ideal development context that often results in active sport participation. In South Africa, there are a number of youth development programmes that not only use football, but also other sporting codes to implement and create sustainable youth development programmes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore best practices in youth development programmes of selected football academies in the Western Cape. This study took place in the greater Cape Town area of the Western Cape and focused on selected football academies who administer youth development programmes. A qualitative approach was used to collect and analyse data for the study. Three key informant interviews and three focus group discussions were conducted with a total sample size of twenty-one participants from the three different academies. Focus group participants were purposively selected from the under fourteen, under sixteen and under eighteen teams from each football academy. The data from the study was collected and analysed through the lens of the Positive Youth Development perspective. -

Orlando Pirates V Supersport United

HIGHLANDS PARK VS POLOKWANE CITY Tuesday, September 17 at 19h30 Semifinal, second leg Makhulong Stadium PREVIOUS MEETINGS IN THE MTN8 2019 Semifinal, 1st leg Polokwane 0 Highlands 0 MTN8 RECORD Total Polokwane Highlands Home Home Played 1 1 0 Polokwane Won 0 0 0 Highlands Won 0 0 0 Drawn 1 1 0 Polokwane Goals 0 0 0 Highlands Goals 0 0 0 ALL PREVIOUS MEETINGS 2016/17 Polokwane 3 (Mncwango, Jembula, J. Maluleke) Highlands 2 (Mbesuma pen, Mashumba) Highlands 1 (Shalulile) Polokwane 1 (Jembula) 2018/19 Polokwane 2 (Anas, W. Maluleke) Highlands 2 (Mvala, Sekola) Highlands 0 Polokwane 2 (Musona, Tlolane) 2019/20 MTN8 semifinal, first leg – Polokwane 0 Highlands 0 SUMMARY League matches in brackets Total Polokwane Highlands Home Home Played 5 (2) 3 (2) 2 (2) Polokwane Won 2 (2) 1 (1) 1 (1) Highlands won 0 0 0 Drawn 3 (2) 2 (1) 1 (1) Polokwane Goals 8 (8) 5 (5) 3 (3) Highlands Goals 5 (5) 4 (4) 1 (1) GOALSCORERS Polokwane 2 goals – Jembula 1 – Mncwango, J. Maluleke, Anas, W. Maluleke, Musona, Tlolane Highlands 1 goal – Mbesuma, Mashumba, Shalulile, Mvala, Sekola RECORDS Polokwane Biggest Win: 2-0 (2018/19) Highlands Biggest Win: - Most goal in a match: 5 – Polokwane 3 Highlands 2 (2016/17) HIGHLANDS PARK – 2019 MTN8 STATS NAME MIN ST SI SO B G YC RC M. Heugh 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 T. Ngobeni 180 2 0 0 0 0 1 0 G. Etafia 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 L. Mzava 52 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 B. -

Plus De 9 Millions D'élèves Rejoignent Ce Mercredi Les

MINISTÈRE DE LA JUSTICE LA DÉTENUE MESSOUSSI SAMIRA JOUIT DE TOUS SES DROITS P. 3 MDN GAÏD SALAH EN VISITE DE TRAVAIL ET D’INSPECTION À LA 4ÈME RÉGION MILITAIRE P. 2 Lundi 2 Septembre 2019 - N°7735 - Prix: 20 DA - 13, Cité Djamel Oran - Tél: 041 85 80 48 - Fax: 041 85 82 54 - www.ouestribune-dz.com ENTREPRISES DES PATRONS INCARCÉRÉS Loukal annonce l’imminence du dégel des comptes bancaires Lire page 3 INONDATIONS À M’SILA ET À TEBESSA BELABED ANNONCE DES AMÉLIORATIONS LA PROTECTION CIVILE AU PROFIT DU SECTEUR SAUVE UNE FAMILLE ET UN ENFANT P. 2 ALGÉRIE - BÉNIN PLUS DE 9 MILLIONS D’ÉLÈVES BELMADI DÉVOILE UNE REJOIGNENT CE MERCREDI LISTE DE 23 JOUEURSP. 12 LES BANCS DE L’ÉCOLE P. 2 2 Ouest Tribune Lundi 2 Septembre 2019 EVENEMENT BELABED ANNONCE DES AMÉLIORATIONS AU PROFIT MDN DU SECTEUR Gaïd Salah en visite de Plus de 9 millions d’élèves rejoignent ce mercredi travail et d’inspection à la 4ème Région les bancs de l’école militaire C’est à partir de ce mercredi que plus de 9 millions d’élèves, tous cycles confondus, vont rejoindre les bancs de e général de corps d’Armée, l’école, une date marquant le début de l’année scolaire 2019-2020. LAhmed Gaïd Salah, vice-ministre de la Défense nationale, chef d’état- Samir Hamiche l’ouverture de 8040 nou- élèves à travers l’acquisi- tion, les secteurs de la San- liste des manuels scolaires major de l’Armée nationale veaux postes budgétaires, tion de 1000 nouveaux té, de la Formation profes- «comprend 22 livres pour populaire, effectuera à partir de n termes de chiffres dont 1061 postes pédago- bus», a-t-il fait savoir. -

MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS and HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 Sportbusiness Group All Rights Reserved

THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 SportBusiness Group All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. The information contained in this publication is believed to be correct at the time of going to press. While care has been taken to ensure that the information is accurate, the publishers can accept no responsibility for any errors or omissions or for changes to the details given. Readers are cautioned that forward-looking statements including forecasts are not guarantees of future performance or results and involve risks and uncertainties that cannot be predicted or quantified and, consequently, the actual performance of companies mentioned in this report and the industry as a whole may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Author: David Walmsley Publisher: Philip Savage Cover design: Character Design Images: Getty Images Typesetting: Character Design Production: Craig Young Published by SportBusiness Group SportBusiness Group is a trading name of SBG Companies Ltd a wholly- owned subsidiary of Electric Word plc Registered office: 33-41 Dallington Street, London EC1V 0BB Tel. +44 (0)207 954 3515 Fax. +44 (0)207 954 3511 Registered number: 3934419 THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Author: David Walmsley THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS -

BMO Management Strategies of Football Clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie

BSc-Thesis – BMO Management strategies of football clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie Name Student: Mylan Pouwels Registration Number: 991110669120 University: Wageningen University & Research (WUR) Study: BBC (Business) Thesis Mentor: Jos Bijman Date: 1-23-2020 Chair Group: BMO Course Code: YSS-81812 Foreword From an early age I already like football. I like it to play football by myself, to watch it on television, but also to read articles about football. The opportunity to combine my love for football with a scientific research for my Bachelor Thesis, could not be better for me. During an orientating conversation about the topic for my Bachelor Thesis with my thesis mentor Jos Bijman, I mentioned that I was always interested in the management strategies of organizations. What kind of choices an organization makes, what kind of resources an organization uses, what an organization wants to achieve and its performances. Following closely this process in large organizations is something I like to do in my leisure time. My thesis mentor Jos Bijman asked for my hobbies and he mentioned that there was a possibility to combine my interests in the management strategies of organizations with my main hobby football. In this way the topic Management strategies of football clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie was created. The Bachelor Thesis Management strategies of football clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie is executed in a qualitative research, using a literature study. This Thesis is written in the context of my graduation of the study Business-and Consumer Studies (specialization Business) at the Wageningen University and Research. From October 28 2019 until January 23 I have been working on the research and writing of my Thesis. -

Elite Training Camps at Aspire Academy a Win for Everyone

14 Thursday, January 16, 2020 Sports Milan cruise Elite training camps at Aspire into Italian Cup last eight AFP Academy a win for everyone MILAN EVEN with Zlatan Ibrahimovic TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK They faced former Dutch in- resting on the bench, AC Mi- DOHA Top European clubs like Bayern Munich, ternational and 2010-11 UEFA lan cruised past SPAL 3-0 on Champions League-winner with Wednesday to reach the last THREE years before the first PSV Eindhoven and Club Brugge all FC Barcelona, Ibrahim Affe- eight of the Italian Cup. ball is kicked at the 2022 FIFA lay, and 17-year-old Mohamed Later, Juventus took on World Cup Qatar, the coun- visited Doha for their winter camps Amine Ihattaren, a star on the Udinese without Cristiano try has established itself as a rise, in a crossbar challenge. Ronaldo who the club tweeted leading destination for inter- “It’s always great to share shortly before kick off was suf- national football stars. A major experiences with young play- fering from sinusitis. reason for the success is the ers and these boys are really In Florence, Pol Lirola shot incredible facilities and know- talented,” Affelay praised the 10-man Fiorentina past Atal- how that Aspire Academy of- skills of Afifa and his team- anta 2-1 to set up a quarter-final fers top clubs that choose Doha mates. “I remember with PSV against Inter Milan. for their winter training camps. at the Al Kass International In Milan, Krzysztof Piatek, In early 2020, some of Eu- Cup at Aspire Academy in who is reportedly on the verge of rope’s elite visited the country 2017,” Ihattaren told the boys. -

Thomas Müller - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Thomas Müller - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thom... Thomas Müller From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Thomas Müller (German pronunciation: [ˈtʰoː.mas ˈmʏ.lɐ]; Thomas Müller born 13 September 1989) is a German footballer who plays for Bayern Munich and the German national team. Müller plays as a midfielder or forward, and has been deployed in a variety of attacking roles – as an attacking midfielder, second striker, and on either wing. He has been praised for his positioning, team work and stamina, and has shown consistency in scoring and creating goals. A product of Bayern's youth system, he made his first-team breakthrough in the 2009–10 season after Louis van Gaal was appointed as the main coach; he played almost every game as the club won the league and cup double and reached the Champions League final. This accomplishment earned him an international call-up, and at the end of the season he was named in Germany's squad for the 2010 World Cup, where he scored five goals in six appearances Müller with Germany in 2012 as the team finished in third place. He was named as the Personal information Best Young Player of the tournament and won the Golden [1] Boot as the tournament's top scorer, with five goals and Full name Thomas Müller three assists. He also scored Bayern's only goal in the Date of birth 13 September 1989 Champions League final in 2012, with the team eventually Place of birth Weilheim, West Germany losing on penalties. -

A Perfect Script? Manchester United's Class of '92. Journal of Sport And

Citation: Dart, J and McDonald, P (2017) A Perfect Script? Manchester United’s Class of ‘92. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 41 (2). pp. 118-132. ISSN 1552-7638 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516685272 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/3425/ Document Version: Article (Accepted Version) The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law. The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team. We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Each thesis in the repository has been cleared where necessary by the author for third party copyright. If you would like a thesis to be removed from the repository or believe there is an issue with copyright, please contact us on [email protected] and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. This is the pre-publication version To cite this article: Dart, J. and McDonald, P. (2016) A Perfect Script? Manchester United’s Class of ’92 Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 1-17 Article first published online: December 23, 2016 To link to this article: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516685272 A Perfect Script? Manchester United's Class of ‘92 Abstract The Class of ‘92 is a documentary film which features six Manchester United F.C. -

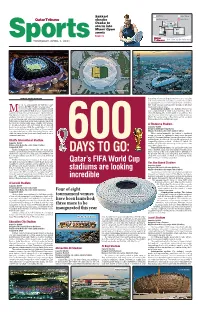

Days to Go: Lation

Sakkari QatarTribune Qatar_Tribune shocks QatarTribuneChannel qatar_tribune Osaka to storm into Miami Open semis PAGE 15 THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2021 Ahmad Bin Ali Stadium Al Janoub Stadium Khalifa International Stadium TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK hospitality. This uniquely Qatari stadium comes complete DOHA with a state-of-the-art retractable roof and is surrounded by 400,000m² of green spaces for the local community. ARCH 31, 2021 marked the 600-day count- The venue will host nine matches through to the semi- down to the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™. finals stage of Qatar 2022. THE first WorldC up in the Middle East and Construction update: The stadium structure has Arab world will kick off on 21 November and been completed and is ready to host matches. This in- Mconclude 28 days later on 18 December – Qatar National cludes the laying of the stadium pitch in record time. This Day. Qatar’s infrastructure plans are well advanced. Four year, the venue achieved a high sustainability rating from stadiums have been inaugurated, the new metro system GSAS. The surrounding Al Bayt Park opened on Qatar is up and running, and a host of expressways have been National Sports Day in February 2020. built. Here’s a closer look at the eight stadiums which will host matches during Qatar 2022. Khalifa International, Al Janoub, Education City and Ahmad Bin Ali have all Al Thumama Stadium hosted major matches, while the construction of Al Bayt Capacity: 40,000 has been completed. Along with Al Bayt, Al Thumama and Designer: Arab Engineering Bureau Ras Abu Aboud are set to be inaugurated during 2021, Distance from Doha city centre: 12km (7 miles) while the venue for the Qatar 2022 final, Lusail, is set to With a design inspired by the ‘gahfiya’, a traditional open early next year. -

1 Day Montessori Football Workshop - Age 3-6

Register NOW 1 DAY MONTESSORI FOOTBALL WORKSHOP - AGE 3-6 “Tennis, football and the like do not have for their sole purpose the accurate moving of a ball but they challenge us to acquire a new skill -something lacking before - and this feeling of enhancing our abilities is the real source of delight in the game” Maria Montessori This workshop is for everyone who (dis)believes that sports and Montessori complement each other. With hundreds of millions of children and adults playing and enjoying the game, football is by far the most popular sports in the world. Since football is universal in its appeal to children, we can tap into it to accelerate learning. It is a scientific fact that sports can enhance physical, psychological, social and academic development of children leading to stronger, healthier and more productive adults. The Montessori environment is the best environment for the development of the child, therefore also for sports development. The Montessori Football program is unique in the sense that it focuses on training (Montessori) teachers, rather than sports trainers. The Montessori Football program places the child central in the sports training, while incorporating Montessori teaching principles and practices. Attend this workshop and learn: • About the benefits of sports and football to the Montessori child (3-6 years) • The concept of connecting Montessori principles to football training • The basic tenets of a prepared football environment • To develop your own ball skills • To observe football training videos Participants will receive an official certificate of attendance provided by Montessori Football and Association Montessori Internationale (AMI).