African American Historic Context CH V-IX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Historic Landmark Nomination New

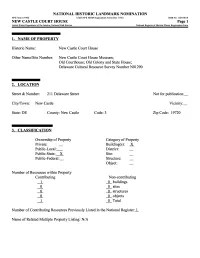

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: New Castle Court House Other Name/Site Number: New Castle Court House Museum; Old Courthouse; Old Colony and State House; Delaware Cultural Resource Survey Number NO 1290 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 211 Delaware Street Not for publication: City/Town: New Castle Vicinity:_ State: DE County: New Castle Code: 3 Zip Code: 19720 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): JL Public-Local:__ District: _ Public-State:_X. Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Non-contributing 1 0 buildings 0 0 sites 0 0 structures 0 0 objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, N ational Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Imperial Tobacco Australia Limited

Imperial Tobacco Australia Limited Submission to the House Standing Committee on Health and Ageing regarding the Inquiry into Plain Tobacco Packaging 22 July 2011 www.imperial-tobacco.com An IMPERIAL TOBACCO GROUP company Registered Office: Level 4, 4-8 Inglewood Place, Norwest Business Park, Baulkham Hills NSW 2153 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2 COMPANY BACKGROUND 6 3 NO CREDIBLE RESEARCH TO SUPPORT THE INTRODUCTION OF PLAIN PACKAGING 7 4 INCREASED TRADE IN ILLICIT TOBACCO 10 4.1 Combating counterfeit product 11 4.2 Illicit trade impact from unproven regulations 14 4.3 Plain Packaging is not an FCTC obligation 15 4.4 Plain Packaging will place Australia in breach of FCTC obligations 16 5 PLAIN PACKAGING WILL BREACH THE LAW AND INTERNATIONAL TREATIES 19 5.1 Specific Breaches of the TRIPS Agreement 20 5.2 Plain Packaging will breach the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade 25 5.3 Breaches of Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral Investment Treaties 27 5.4 Threat to Australia’s reputation 28 6 THE BILL IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL 29 7 NEGATIVE IMPACT ON COMPETITION, CONSUMERS AND RETAILERS 32 7.1 Adverse effects on consumers and retailers 32 7.2 Known effects on businesses and retailers 34 8 INADEQUATE TIME FOR COMPLIANCE 36 8.1 Uncertainty created by incomplete draft Regulations 38 8.2 Previous timelines at introduction of Graphic Health Warnings 2005/6 40 8.3 The Bill and draft Regulations omit important consumer information 41 8.4 Strict Liability and Criminal Penalties 42 9 AUSTRALIA the “NANNY STATE” 43 9.1 Over regulation 43 -

Daguerreian Annual 1990-2015: a Complete Index of Subjects

Daguerreian Annual 1990–2015: A Complete Index of Subjects & Daguerreotypes Illustrated Subject / Year:Page Version 75 Mark S. Johnson Editor of The Daguerreian Annual, 1997–2015 © 2018 Mark S. Johnson Mark Johnson’s contact: [email protected] This index is a work in progress, and I’m certain there are errors. Updated versions will be released so user feedback is encouraged. If you would like to suggest possible additions or corrections, send the text in the body of an email, formatted as “Subject / year:page” To Use A) Using Adobe Reader, this PDF can be quickly scrolled alphabetically by sliding the small box in the window’s vertical scroll bar. - or - B) PDF’s can also be word-searched, as shown in Figure 1. Many index citations contain keywords so trying a word search will often find other instances. Then, clicking these icons Figure 1 Type the word(s) to will take you to another in- be searched in this Adobe Reader Window stance of that word, either box. before or after. If you do not own the Daguerreian Annual this index refers you to, we may be able to help. Contact us at: [email protected] A Acuna, Patricia 2013: 281 1996: 183 Adams, Soloman; microscopic a’Beckett, Mr. Justice (judge) Adam, Hans Christian d’types 1995: 176 1995: 194 2002/2003: 287 [J. A. Whipple] Abbot, Charles G.; Sec. of Smithso- Adams & Co. Express Banking; 2015: 259 [ltr. in Boston Daily nian Institution deposit slip w/ d’type engraving Evening Transcript, 1/7/1847] 2015: 149–151 [letters re Fitz] 2014: 50–51 Adams, Zabdiel Boylston Abbott, J. -

Supplementary Table 10.7

Factory-made cigarettes and roll-your-own tobacco products available for sale in January 2019 at major Australian retailers1 Market Pack Number of Year Tobacco Company segment2 Brand size3 variants Variant name(s) Cigarette type introduced4 British American Super-value Rothmans5 20 3 Blue, Gold, Red Regular 2015 Tobacco Australia FMCs 23 2 Blue, Gold Regular 2018 25 5 Blue, Gold, Red, Silver, Menthol Green Regular 2014 30 3 Blue, Gold, Red Regular 2016 40 6 Blue, Gold, Red, Silver, Menthol Green, Black6 Regular 2014 50 5 Blue, Gold, Red, Silver, Menthol Green Regular 2016 Rothmans Cool Crush 20 3 Blue, Gold, Red Flavour capsule 2017 Rothmans Superkings 20 3 Blue, Red, Menthol Green Extra-long sticks 2015 ShuangXi7 20 2 Original Red, Blue8 Regular Pre-2012 Value FMCs Holiday 20 3 Blue, Gold, Red Regular 20189 22 5 Blue, Gold, Red, Grey, Sea Green Regular Pre-2012 50 5 Blue, Gold, Red, Grey, Sea Green Regular Pre-2012 Pall Mall 20 4 Rich Blue, Ultimate Purple, Black10, Amber Regular Pre-2012 40 3 Rich Blue, Ultimate Purple, Black11 Regular Pre-2012 Pall Mall Slims 23 5 Blue, Amber, Silver, Purple, Menthol Short, slim sticks Pre-2012 Mainstream Winfield 20 6 Blue, Gold, Sky Blue, Red, Grey, White Regular Pre-2012 FMCs 25 6 Blue, Gold, Sky Blue, Red, Grey, White Regular Pre-2012 30 5 Blue, Gold, Sky Blue, Red, Grey Regular 2014 40 3 Blue, Gold, Menthol Fresh Regular 2017 Winfield Jets 23 2 Blue, Gold Slim sticks 2014 Winfield Optimum 23 1 Wild Mist Charcoal filter 2018 25 3 Gold, Night, Sky Charcoal filter Pre-2012 Winfield Optimum Crush 20 -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPSForm10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) . ^ ;- j> United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. _X_New Submission _ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________________ The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts 1783-1865______________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) C. Form Prepared by_________________________________________ name/title Kathrvn Grover and Neil Larson. Preservation Consultants, with Betsy Friedberg and Michael Steinitz. MHC. Paul Weinbaum and Tara Morrison. NFS organization Massachusetts Historical Commission________ date July 2005 street & number 220 Morhssey Boulevard________ telephone 617-727-8470_____________ city or town Boston____ state MA______ zip code 02125___________________________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National -

ITA APC Annual Report & Action Plan

Imperial Tobacco Australia Limited Australian Packaging Covenant Annual Report and Action Plan 2016-17 Annual Report 2017-18 Action Plan Company Profile STATEMENT OF COMMITMENT This year, Imperial Tobacco Australia has renewed its support for the Australian Packaging Covenant and is enthusiastic to support the new strategy and direction of the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation. ITA is a long-term signatory to the APC, first signing to the Covenant in 2002, and has remained committed to address sustainable packaging in ways relevant for our business. Packaging sustainability is a key pillar in our environment sustainability approach to minimise our environmental impact. This Annual Report is the first report under the APCO’s new strategy and reporting framework. The Report covers our financial reporting period - October 2016 to September 2017. In FY 2017, we worked to set a new baseline to measure packaging sustainability against the packaging sustainability framework reporting tool. Our key achievements to date include: Reviewed 100% of our packaging using the Sustainable Packaging Guidelines to identify opportunities which could improve the sustainability of our packaging Introduced 2 new packaging formats which have improved product and packaging sustainability, however unfortunately these have since been withdrawn from market. Introduced a new packaging sustainability assessment process for new packaging or packaging changes Set a baseline for renewable packaging – 86% by weight of packaging is made from renewable materials - and working towards setting a baseline for packaging optimisation and recoverability Commenced review of our business to business packaging to understand opportunities to reduce single use business to business packaging. Maintained best practice recycling systems at head office – 78% of our waste was recycled in the reporting period. -

Uncle Tom's Cabin

Revised Pages Excerpted from Tracy C. Davis and Stefka Mihaylova, eds., Journal of Transnational American Studies 11.2 (2020) Uncle Tom’s Cabins: A Transnational History of America’s Most Mutable Book (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018). Copyright 2018 by Tracy C. Davis and Stefka Mihaylova. Reprinted with permission from University of Michigan Press. Kahlil Chaar- Pérez The Bonds of Translation: A Cuban Encounter with Uncle Tom’s Cabin Trough numerous translations, adaptations, and performances, mid- nineteenth- century sentimental communities across the world embraced Harriet Beecher Stowe’s plea in Uncle Tom’s Cabin to “feel right” in op- posing chattel slavery as “a system which confounds and confuses every principle of Christianity and morality” (452– 53). Although the British and French governments had already abolished it, slavery was still rampant in the United States, Brazil, and the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico during the 1850s, while serfdom subsisted in Russia. Moved by the novel’s afecting depiction of the horrors of enslavement, a transatlantic public coalesced around the universalist moral values through which Stowe ex- pressed her call for abolition: “See, then, to your sympathies in this mat- ter! Are they in harmony with the sympathies of Christ? or [sic] are they swayed and perverted by the sophistries of world policy?” (452). In the Protestant brand of sentimentalism found throughout Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the experience of sympathizing with the enslaved other is circumscribed within a pre- ideological order of feelings. In the pursuit of a “right” feeling determined by the universal spirit of “Christianity,” the ideal sympathetic subject is able to transcend the artifcial divisions fostered by the politi- cal sphere (“world policy”). -

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

Underground Railroad Byway Delaware

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway Delaware Chapter 3.0 Intrinsic Resource Assessment The following Intrinsic Resource Assessment chapter outlines the intrinsic resources found along the corridor. The National Scenic Byway Program defines an intrinsic resource as the cultural, historical, archeological, recreational, natural or scenic qualities or values along a roadway that are necessary for designation as a Scenic Byway. Intrinsic resources are features considered significant, exceptional and distinctive by a community and are recognized and expressed by that community in its comprehensive plan to be of local, regional, statewide or national significance and worthy of preservation and management (60 FR 26759). Nationally significant resources are those that tend to draw travelers or visitors from regions throughout the United States. National Scenic Byway CMP Point #2 An assessment of the intrinsic qualities and their context (the areas surrounding the intrinsic resources). The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway offers travelers a significant amount of Historical and Cultural resources; therefore, this CMP is focused mainly on these resource categories. The additional resource categories are not ignored in this CMP; they are however, not at the same level of significance or concentration along the corridor as the Historical and Cultural resources. The resources represented in the following chapter provide direct relationships to the corridor story and are therefore presented in this chapter. A map of the entire corridor with all of the intrinsic resources displayed can be found on Figure 6. Figures 7 through 10 provide detailed maps of the four (4) corridors segments, with the intrinsic resources highlighted. This Intrinsic Resource Assessment is organized in a manner that presents the Primary (or most significant resources) first, followed by the Secondary resources. -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress

ANNUAL REPO R T O F THE LIBR ARIAN OF CONGRESS ANNUAL REPORT OF T HE L IBRARIAN OF CONGRESS For the Fiscal Year Ending September , Washington Library of Congress Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC For the Library of Congress on the World Wide Web visit: <www.loc.gov>. The annual report is published through the Public Affairs Office, Office of the Librarian, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -, and the Publishing Office, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -. Telephone () - (Public Affairs) or () - (Publishing). Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Copyediting: Publications Professionals LLC Indexer: Victoria Agee, Agee Indexing Design and Composition: Anne Theilgard, Kachergis Book Design Production Manager: Gloria Baskerville-Holmes Assistant Production Manager: Clarke Allen Library of Congress Catalog Card Number - - Key title: Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP Washington, DC - A Letter from the Librarian of Congress / vii Library of Congress Officers and Consultants / ix Organization Chart / x Library of Congress Committees / xiii Highlights of / Library of Congress Bicentennial / Bicentennial Chronology / Congressional Research Service / Copyright Office / Law Library of Congress / Library Services / National Digital Library Program / Office of the Librarian / A. Bicentennial / . Steering Committee / . Local Legacies / . Exhibitions / . Publications / . Symposia / . Concerts: I Hear America Singing / . Living Legends / . Commemorative Coins / . Commemorative Stamp: Second-Day Issue Sites / . Gifts to the Nation / . International Gifts to the Nation / v vi Contents B. Major Events at the Library / C. The Librarian’s Testimony / D. Advisory Bodies / E. Honors / F. Selected Acquisitions / G. Exhibitions / H. Online Collections and Exhibitions / I. -

Ever Faithful

Ever Faithful Ever Faithful Race, Loyalty, and the Ends of Empire in Spanish Cuba David Sartorius Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Tyeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sartorius, David A. Ever faithful : race, loyalty, and the ends of empire in Spanish Cuba / David Sartorius. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5579- 3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5593- 9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Blacks— Race identity— Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba— Race relations— History—19th century. 3. Spain— Colonies—America— Administration—History—19th century. I. Title. F1789.N3S27 2013 305.80097291—dc23 2013025534 contents Preface • vii A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s • xv Introduction A Faithful Account of Colonial Racial Politics • 1 one Belonging to an Empire • 21 Race and Rights two Suspicious Affi nities • 52 Loyal Subjectivity and the Paternalist Public three Th e Will to Freedom • 94 Spanish Allegiances in the Ten Years’ War four Publicizing Loyalty • 128 Race and the Post- Zanjón Public Sphere five “Long Live Spain! Death to Autonomy!” • 158 Liberalism and Slave Emancipation six Th e Price of Integrity • 187 Limited Loyalties in Revolution Conclusion Subject Citizens and the Tragedy of Loyalty • 217 Notes • 227 Bibliography • 271 Index • 305 preface To visit the Palace of the Captain General on Havana’s Plaza de Armas today is to witness the most prominent stone- and mortar monument to the endur- ing history of Spanish colonial rule in Cuba. -

Black Evangelicals and the Gospel of Freedom, 1790-1890

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 Alicestyne Turley University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Turley, Alicestyne, "SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890" (2009). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 79. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/79 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Alicestyne Turley The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2009 SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 _______________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _______________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Alicestyne Turley Lexington, Kentucky Co-Director: Dr. Ron Eller, Professor of History Co-Director, Dr. Joanne Pope Melish, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2009 Copyright © Alicestyne Turley 2009 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 The true nineteenth-century story of the Underground Railroad begins in the South and is spread North by free blacks, escaping southern slaves, and displaced, white, anti-slavery Protestant evangelicals. This study examines the role of free blacks, escaping slaves, and white Protestant evangelicals influenced by tenants of Kentucky’s Second Great Awakening who were inspired, directly or indirectly, to aid in African American community building.