Allen (1823-1903), Provides a Major Phases: (1) 182-1844, Covering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horace Mann, Sr

HORACE MANN, SR.: ACCELERATING “THE AGENDA OF THE ALMIGHTY” “I look upon Phrenology as the guide of Philosophy, and the handmaid of Christianity; whoever disseminates true Phrenology, is a public benefactor.” — Horace Mann, Sr. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Horace Mann, Sr. HDT WHAT? INDEX HORACE MANN, SR. HORACE MANN, SR. 1796 May 4, Wednesday: Friend Elias Hicks surveyed the land of Thomas Titus and John Titus. Horace Mann was born in Franklin, Massachusetts, son of Thomas Mann and Rebecca Stanley Mann.1 NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT 1. (You’re to understand he wasn’t addressed as “Sr.” when born.) HDT WHAT? INDEX HORACE MANN, SR. HORACE MANN, SR. 1809 June 9, Friday: Horace Mann, Sr.’s father made his will. He left Horace enough to finance a college education, although later, in the grip of the “log cabin” school of greatness, the great Mann would assert that he had been provided only with an “example of an upright life” and a “hereditary thirst for knowledge.” – Since he was encouraging everyone to be like him and rise like him, it would hardly do to tell the truth. Carl Axel Trolle-Wachtmeister became Prime Minister for Justice of Sweden, while Lars von Engeström became Prime Minister for Foreign Affairs. Friend Stephen Wanton Gould wrote in his journal: 6th day 9 of 6 Mo // Early this morning a Packet arrived from NYork & brought the Melancholy intelligence of the Sudden departure out of time of Francis Mallone at the City of Washington he died the 4th of this Mo dropt down in the Street as he was walking to Church with his brother Senator E R Potter & died without a Struggle - My mind has through the day been much occupied on the above melancholy acct, I hope it may prove a solemn warning & help to keep me in rememberance of my final change - ————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— RELIGIOUS SOCIETY OF FRIENDS June 20, Monday: Horace Mann’s father Thomas Mann died. -

Daguerreian Annual 1990-2015: a Complete Index of Subjects

Daguerreian Annual 1990–2015: A Complete Index of Subjects & Daguerreotypes Illustrated Subject / Year:Page Version 75 Mark S. Johnson Editor of The Daguerreian Annual, 1997–2015 © 2018 Mark S. Johnson Mark Johnson’s contact: [email protected] This index is a work in progress, and I’m certain there are errors. Updated versions will be released so user feedback is encouraged. If you would like to suggest possible additions or corrections, send the text in the body of an email, formatted as “Subject / year:page” To Use A) Using Adobe Reader, this PDF can be quickly scrolled alphabetically by sliding the small box in the window’s vertical scroll bar. - or - B) PDF’s can also be word-searched, as shown in Figure 1. Many index citations contain keywords so trying a word search will often find other instances. Then, clicking these icons Figure 1 Type the word(s) to will take you to another in- be searched in this Adobe Reader Window stance of that word, either box. before or after. If you do not own the Daguerreian Annual this index refers you to, we may be able to help. Contact us at: [email protected] A Acuna, Patricia 2013: 281 1996: 183 Adams, Soloman; microscopic a’Beckett, Mr. Justice (judge) Adam, Hans Christian d’types 1995: 176 1995: 194 2002/2003: 287 [J. A. Whipple] Abbot, Charles G.; Sec. of Smithso- Adams & Co. Express Banking; 2015: 259 [ltr. in Boston Daily nian Institution deposit slip w/ d’type engraving Evening Transcript, 1/7/1847] 2015: 149–151 [letters re Fitz] 2014: 50–51 Adams, Zabdiel Boylston Abbott, J. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University M crct. rrs it'terrjt onai A Be" 4 Howe1 ir”?r'"a! Cor"ear-, J00 Norte CeeD Road App Artjor mi 4 6 ‘Og ' 346 USA 3 13 761-4’00 600 sC -0600 Order Number 9238197 Selected literary letters of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, 1842-1853 Hurst, Nancy Luanne Jenkins, Ph.D. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPSForm10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) . ^ ;- j> United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. _X_New Submission _ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________________ The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts 1783-1865______________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) C. Form Prepared by_________________________________________ name/title Kathrvn Grover and Neil Larson. Preservation Consultants, with Betsy Friedberg and Michael Steinitz. MHC. Paul Weinbaum and Tara Morrison. NFS organization Massachusetts Historical Commission________ date July 2005 street & number 220 Morhssey Boulevard________ telephone 617-727-8470_____________ city or town Boston____ state MA______ zip code 02125___________________________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National -

Worcester Lunatic Asylum Records, 1833

AILEICAN .AiTIQUAPJAr SOCIETY Manuscript Collections same of collection: Location; Worcester Lunatic Asylum. Records, 1833—192)3 Octavo vols. “W” i Folio vols. “W” Size of collection: N.U.C,M,C. number: - 1 octave vol., 166 leaves (151 blank); 2 folio vols. N.A. Finding aids For ioation concerning the hospital, see Reports...relatjn to the State I Lunatic Hosnital at Worce Mass. (Boston: State Senate, and Charles (New York Lewis Historical Publishing curce of collection: Qift of Worcester ‘tate Hospital, 198)3 Collection Dcscription: In 1830, in order to provide care for the mentally- ill in Worcester County, the governor of Massachusetts ordered the erection of a hospital on Summer Street- in Worcester. Commissioners appointed to oversee the new building were Horace Mann (1796—1859), Bezaleel Taft, Jr. (1780—18)36), and William Barron Calhoun (1795— 1865). Dr. Samuel Bay-and Woodward (1787-1850) served as the first superintendent/; physician of the Worcester Lunatic Asylum. The hospital was enlarged in 1835 and was considered one of the best institutions in the country for the treatment of insanity. Its successor was Worcester State Hospital, located on Belmont Street. The majority of the records of the asylm to 1870 apparently were sent to the Countway Library of Harvard University. This collection contains one octavo volume, 1912—192L, and two folio vol umes, 1833—1873, and 873—1902, recording trustees’ visits to the Worcester Lunatic Asylum. The octavo volume consists of brief comments concerning the satisfactory conditiono at the -

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

Renewing the American Commitment to the Common School Philosophy: School Choice in the Early Twenty-First Century

4 Global Education Review 3(2) Renewing the American Commitment to The Common School Philosophy: School Choice in the Early Twenty-First Century Brian L. Fife Indiana University-Purdue University Abstract The common school philosophy of the nineteenth century in the United States is revisited from a contemporary perspective. Is the basic ethos of the philosophy of Horace Mann and others still relevant today? This question is examined and applied to the conservative advocacy of free markets, individual freedom, and school choice in order to assess the extent to which the delivery of government-supported education is done in a way that upholds the values of the past while simultaneously addressing paramount issues related to social equity, diversity, and social cohesion today. Keywords common school philosophy; Horace Mann; school choice; education vouchers; conservatism; public good; charter schools; accountability; individualism; libertarianism; communitarianism Introduction exists on Mann’s education philosophy (e.g., The idea of free public education for all students Makechnie, 1937; Foster, 1960; and Litz (1975), did not begin with the leader of the nineteenth- the central purpose of this article is to highlight century common school movement, Horace the pertinence and relevance of Mann’s ideals to Mann. Prominent Americans such as Benjamin contemporary debates over school choice, Rush, Thomas Jefferson, and Noah Webster, charter schools, and education vouchers. among others, espoused the notion in their writings long before the 1830s (Fife, 2013, pp. 2- Brief Biographical Sketch of 8; Spring, 2014, pp. 78-79). Yet as Downs (1974) Horace Mann noted: “The impact of Horace Mann’s ideas and Horace Mann was born in Franklin, achievements has been profoundly felt in the Massachusetts on May 4, 1796. -

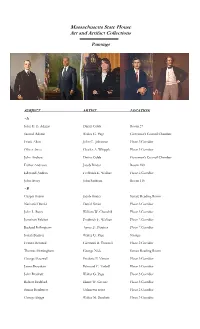

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress

ANNUAL REPO R T O F THE LIBR ARIAN OF CONGRESS ANNUAL REPORT OF T HE L IBRARIAN OF CONGRESS For the Fiscal Year Ending September , Washington Library of Congress Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC For the Library of Congress on the World Wide Web visit: <www.loc.gov>. The annual report is published through the Public Affairs Office, Office of the Librarian, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -, and the Publishing Office, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -. Telephone () - (Public Affairs) or () - (Publishing). Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Copyediting: Publications Professionals LLC Indexer: Victoria Agee, Agee Indexing Design and Composition: Anne Theilgard, Kachergis Book Design Production Manager: Gloria Baskerville-Holmes Assistant Production Manager: Clarke Allen Library of Congress Catalog Card Number - - Key title: Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP Washington, DC - A Letter from the Librarian of Congress / vii Library of Congress Officers and Consultants / ix Organization Chart / x Library of Congress Committees / xiii Highlights of / Library of Congress Bicentennial / Bicentennial Chronology / Congressional Research Service / Copyright Office / Law Library of Congress / Library Services / National Digital Library Program / Office of the Librarian / A. Bicentennial / . Steering Committee / . Local Legacies / . Exhibitions / . Publications / . Symposia / . Concerts: I Hear America Singing / . Living Legends / . Commemorative Coins / . Commemorative Stamp: Second-Day Issue Sites / . Gifts to the Nation / . International Gifts to the Nation / v vi Contents B. Major Events at the Library / C. The Librarian’s Testimony / D. Advisory Bodies / E. Honors / F. Selected Acquisitions / G. Exhibitions / H. Online Collections and Exhibitions / I. -

Melrose-1921.Pdf (11.99Mb)

ANGIER L. GOODWIN, MAYOR CITY OF MELROSE MASSACHUSETTS Annual Reports 1921 WITH Mayor’s Inaugural Address Delivered January 3rd, 1921 PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OP ALDERMEN UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CITY CLERK AND SPECIAL COMMITTEE MBUOSB, MAM. THS MBI«ROSE FREE PRESS. Ibc. 1922 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Boston Public Library https://archive.org/details/cityofmelroseann1921melr r f I HO :* • • ) . •i. : . J 1 \ J * Y n f ^ . CrM “3 5 Z 52 c_ Inaugural Address Mayor of Melrose HON. ANGIER L GOODWIN DELIVERED JANUARY 3. 1921 Mr. President, Members of the Board of Aldermen: To us has been intrusted the responsibility of directing the affairs of the city during the current year. It is my privilege to address the Board of Aldermen, at this, the commencement of our duties, on general conditions. Further communications and recommendations will be ad- dressed to the legislative branch from time to time as occasion may arise. The fiscal condition of the city is good. Our total net debt on Dec. 31, 1920, is .$608,203.90. Our taxable valuation is $21,085,400,001. Our borrow- ing capacity is $152,603.33. While our financial condition remains satisfactory, giving us a credit and financial rating far above the average of the cities of the Common- wealth, yet we should exercise the utmost vigilance in our appropriations and expenditures. We begin our labors at a period in our national economic life which is most unsettled. I have grave hesitation in suggesting various public improvements of a major character which I would gladly recom« mend if general economic conditions were normal. -

Supplement to the History and Social Science Curriculum Framework

Resources for History and Social Science Draft Supplement to the 2018 Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Framework Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education May 15, 2018 Copyediting incomplete This document was prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Members Mr. Paul Sagan, Chair, Cambridge Mr. Michael Moriarty, Holyoke Mr. James Morton, Vice Chair, Boston Mr. James Peyser, Secretary of Education, Milton Ms. Katherine Craven, Brookline Ms. Mary Ann Stewart, Lexington Dr. Edward Doherty, Hyde Park Dr. Martin West, Newton Ms. Amanda Fernandez, Belmont Ms. Hannah Trimarchi, Chair, Student Advisory Ms. Margaret McKenna, Boston Council, Marblehead Jeffrey C. Riley, Commissioner and Secretary to the Board The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, an affirmative action employer, is committed to ensuring that all of its programs and facilities are accessible to all members of the public. We do not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, national origin, race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation. Inquiries regarding the Department’s compliance with Title IX and other civil rights laws may be directed to the Human Resources Director, 75 Pleasant St., Malden, MA, 02148, 781-338-6105. © 2018 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Permission is hereby granted to copy any or all parts of this document for non-commercial educational purposes. Please credit the “Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.” Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, MA 02148-4906 Phone 781-338-3000 TTY: N.E.T. Relay 800-439-2370 www.doe.mass.edu Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, Massachusetts 02148-4906 Telephone: (781) 338-3000 TTY: N.E.T. -

City of Melrose Annual Report

ANGIER L. GOODWIN. MAYOR CITY OF MELROSE MASSACHUSETTS Annual Reports 1922 WITH Mayor’s Inaugural Address Delivered January 2nd, 1922 PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF ALDERMEN UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CITY CLERK AND SPECIAL COMMITTEE THE COPLEY PRESS, Melrose. Mass. 1923 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Boston Public Library https://archive.org/details/cityofmelroseann1922mel INAUGURAL ADDRESS OF Hon. Angier L. Goodwin Mayor of Melrose, Massachusetts JANUARY SECOND NINETEEN HUNDRED TWENTY-TWO Mr. President and Members of the Board of Aldermen: We start today a new year in the civic life of Melrose. Problems of considerable moment are calling for consideration. There has never been a time in the history of the city when it has been more essential for its officials to exercise their highest judgment. The tax payers look to us to keep the tax rate down, and yet we know that there are certain automatic increases in some city departments, and we are also confronted with the fact that there will be a decrease in the amount we shall receive from the State for corporation taxes. The conclusion is inevitable that we must make every effort to keep at a minimum the amount to be raised by taxation for current expenses. But our responsibility is not only to the tax-payer of today; it is also to the citizen of tomorrow. We must go forward as a munici- pality. If we try to stand still, we shall go backward. We must be progressive. Many public improvements have been foregone in the past few years, which are now crying for attention.