Please Scroll Down for Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORT PH List Numerical

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People Jerusalem (CAHJP) ORT PHOTO COLLECTION – ORT/Ph ORT (organization for rehabilitation and training) was founded in 1880 as a Russian, Jewish organization to promote vocational training of skilled trades and agriculture and functioned there until the outbreak of World War I, which together with the Bolshevik Revolution caused a virtual cessation of its activities. In 1920 ORT was reestablished in Berlin as an international organization and began operating in Russia and the countries that had formerly been part of Russia – Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Bessarabia – as well as in Germany, France, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the offices were moved from Berlin to Paris and subsequently to Marseilles after the capture of Paris by the Germans in 1940. After World War II the headquarters of World ORT Union were set up in Genève, from which they later moved to London, where they reside to this day. The list below is arranged according to serial numbers each of which represents a country. The sequencing is based on the original order of photos inside the former metal binders, hence towns within a country are listed randomly, not alphabetically. Displaying the photo collection of the ORT files from the headquarters in London, most of the descriptions are the original captions from the former binders. LIST OF REFERENCE CODES NUMERICAL ORT/PH 1 Algeria ORT/PH 13 Tunisia ORT/PH 2 Germany ORT/PH 14 South Africa ORT/PH 3 Austria ORT/PH 1 5 Uruguay ORT/PH 4 -

Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I

JEWISH REVIEW Number 2, Summer 2010 $6.95 OF BOOKS Ruth R. Wisse The Poet from Vilna Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I. Cohen on Camondo Treasure David Sorkin on Steven J. Moses Zipperstein Montefiore The Spy who Came from the Shtetl Anita Shapira The Kibbutz and the State Robert Alter Yehuda Halevi Moshe Halbertal How Not to Pray Walter Russell Mead Christian Zionism Plus Summer Fiction, Crusaders Vanquished & More A Short History of the Jews Michael Brenner Editor Translated by Jeremiah Riemer Abraham Socher “Drawing on the best recent scholarship and wearing his formidable learning lightly, Michael Publisher Brenner has produced a remarkable synoptic survey of Jewish history. His book must be considered a standard against which all such efforts to master and make sense of the Jewish Eric Cohen past should be measured.” —Stephen J. Whitfield, Brandeis University Sr. Contributing Editor Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-14351-4 July Allan Arkush Editorial Board Robert Alter The Rebbe Shlomo Avineri The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson Leora Batnitzky Samuel Heilman & Menachem Friedman Ruth Gavison “Brilliant, well-researched, and sure to be controversial, The Rebbe is the most important Moshe Halbertal biography of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson ever to appear. Samuel Heilman and Hillel Halkin Menachem Friedman, two of the world’s foremost sociologists of religion, have produced a Jon D. Levenson landmark study of Chabad, religious messianism, and one of the greatest spiritual figures of the twentieth century.” Anita Shapira —Jonathan D. Sarna, author of American Judaism: A History Michael Walzer Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-13888-6 J. -

Laws of the State of Israel

LAWS OF THE STATE OF ISRAEL VOL 16 5722—1961/62 FROM 30th TISHRI, 5722 — 10.10.61 TO 8th AV, 5722 — 8.8.62 Authorised Translation from the Hebrew Prepared at the Ministry of Justice PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER LAWS OF THE STATE OF ISRAEL VOL. 16 5722—1961/62 FROM 30th TISHRI, 5722 — 10.10.61 TO 8th AV, 5722 — 8.8.62 Authorised Translation from the Hebrew Prepared at the Ministry of Justice PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER CONTENTS Page Laws ••< *•• ••• ••• ,•••< • • •i !••« !• • •. 3 Budget Laws 122 Index of Laws in the Order of the Dates of Their Adoption by the Knesset 146 Alphabetical Index of Laws 149 Index of Budget Laws 151 EXPLANATIONS l.R. (Iton Rishmi) The Official Gazette during the tenure of the Provisional Council of State Reshumot The Official Gazette since the inception of the Knesset Sections of Reshumot referred to in this translation : Yalkut Ha-Pirsumim — Government Notices Sefer Ha-Chukkim — Principal Legislation Chukkei Taktziv — Budgetary Legislation Kovetz Ha-Takkanot — Subsidiary Legislation Hatza'ot Chok — Bills Chukkei Taktziv (Hatza'ot) — Budget Bills Dinei Yisrael (from No. 2: -— The revised, up-to-date and binding Dinei Medinat Yisrael) Hebrew text of legislation enacted (Nusach Chadash) before the establishment of the State P.G. (Palestine Gazette) — The Official Gazette of the Man• datory Government Laws of Palestine — The 1934 revised edition of Pales• tine legislation (Drayton) LSI Laws of the State of Israel LAWS (No. 1) ABSORPTION LOAN LAW, 5722—1961* 1. In this Law — (1) every term shall have -

The Knesset Building in Giv'at Ram: Planning and Construction

The Knesset Building in Giv’at Ram: Planning and Construction Originally published in Cathedra Magazine, 96th Edition, July 2000 Written by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef Introduction Already in the early days of modern Zionism, it was clear to those who envisioned the establishment of a Jewish State, and those who acted to realize the vision, that once it was established, it would be a democracy, in which a parliament would be built. In his book Altneuland (written in 1902), Theodor Herzl, described the parliament of the Jewish state in Jerusalem in the following words: “[A] great crowd was massed before (the Congress House). The election was to take place in the lofty council chamber built of solid marble and lighted from above through matte glass. The auditorium seats were still empty, because the delegates were still in the lobbies and committee rooms, engaged in exceedingly hot discussion…" 1 In his book Yerushalayim Habnuya (written in 1918), Boris Schatz, who had established the Bezalel school of arts and crafts, placed the parliament of the Jewish State on Mount Olives: "Mount Olives ceased to be a mountain of the dead… it is now the mountain of life…the round building close to [the Hall of Peace] is our parliament, in which the Sanhedrin sits".2 When in the 1920s the German born architect, Richard Kaufmann, presented to the British authorities his plan for the Talpiot neighborhood, that was designed to be a Jerusalem garden neighborhood, it included an unidentified building of large dimensions. When he was asked about the meaning of the building he relied in German: "this is our parliament building". -

Peace, Peace, When There Is No Peace (Israel and the Arabs 1948–1961)

Peace, Peace, When There Is No Peace (Israel and the Arabs 1948–1961) N. Israeli (Akiva Orr and Moshé Machover) Translated from Hebrew by Mark Marshall ii Introduction [to the first edition]................................................................................... xv Chapter 1: “Following Clayton’s Participation in the League’s Meetings”................ 1 Chapter 2: Borders and Refugees ................................................................................. 28 Map: How the Palestinian state was divided............................................................ 42 Chapter 3: Israel and the Powers (1948-1955)............................................................. 83 Chapter 4: Israel and Changes in the Arab World ................................................... 141 Chapter 5: Reprisal Actions......................................................................................... 166 Chapter 6: “The Third Kingdom of Israel” (29/11/56 – 7/3/57).............................. 225 Chapter 7: Sinai War: Post-Mortem........................................................................... 303 Chapter 8: After Suez................................................................................................... 394 Chapter 9: How is the Problem to be Solved?............................................................ 420 Appendices (1999) ......................................................................................................... 498 Appendix 1: Haaretz article on the 30th anniversary of “Operation Qadesh” -

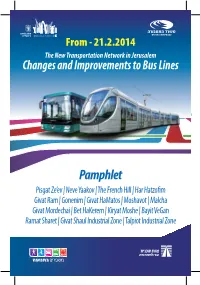

Changes and Improvements to Bus Lines

From - 21.2.2014 The New Transportation Network in Jerusalem Changes and Improvements to Bus Lines Pamphlet Pisgat Ze’ev | Neve Yaakov | The French Hill | Har Hatzofim Givat Ram | Gonenim | Givat HaMatos | Moshavot | Malcha Givat Mordechai | Bet HaKerem | Kiryat Moshe | Bayit VeGan Ramat Sharet | Givat Shaul Industrial Zone | Talpiot Industrial Zone Public transportation in Jerusalem continues to make progress towards providing faster, more efficient and better service Dear passengers, On 21.2.14 the routes of several lines operating in Jerusalem will be changed as part of the continuous improvement of the city’s public transportation system. Great emphasis was put on improving the service and accessibility to the city’s central employment areas: Talpiot, Givat Shaul, the Technological Garden, Malcha and the Government Complex. From now on there will be more lines that will lead you more frequently and comfortably to and from work. The planning of the new lines is a result of cooperation between the Ministry of Transport, the Jerusalem Municipality and public representatives, through the Jerusalem Transport Master Plan team (JTMT). This pamphlet provides, for your convenience, all the information concerning the lines included in this phase: before you is a layout of the new and improved lines, station locations and line changes on the way to your destination. We wish to thank the public representatives who assisted in the planning of the new routes, and to you, the passengers, for your patience and cooperation during the implementation -

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] POLITICAL PARTIES IN A NEW SOCIETY (THE CASE OF ISRAEL) Ovadia Shapiro PhD. Thesis University of Glasgow 1971. ProQuest Number: 10647406 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uesL ProQuest 10647406 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. ProQuest LLO. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.Q. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to acknowledge debts of gratitude to; 1. -

RESOLUTIONS of the 25Th ZIONIST CONGRESS

RESOLUTIONS of the 25th ZIONIST CONGRESS with A Summary of the Proceedings and the Composition of the Congress Jerusalem December 27, 1960-January 11, 1961 <JS( PUBLISHED BY THE ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE RESOLUTIONS of the 25th ZIONIST CONGRESS with A Summary of the Proceedings and the Composition of the Congress Jerusalem December 27,1960-January 11,1961 PUBLISHED BY THE ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE Printed under the supervision of the Publishing Department of the Jewish Agency by The Jerusalem Post Press, Jerusalem Translated from the Hebrew Original Printed in Israel CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Summary of Proceedings 5 Composition of the Congress 12 RESOLUTIONS OF THE CONGRESS A. Political Problems 17 B. Immigration 21 C. Youth Aliyah 24 D. Absorption 25 E. Agricultural Settlement 28 F. Education and Culture in the Diaspora 30 G. Organization 34 H. Legal Matters 38 I. Youth and Hechalutz 39 J. Information 45 K. Economic Affairs 47 L. Finance and Budget 49 M. Funds and Campaigns 50 N. Further Representatives on the General Council and the Executive 53 O. Elections 53 APPENDICES List of Members of the 25th Zionist Congress 60 I. SUMMARY OF PROCEEDINGS The 25th Zionist Congress convened in Jerusalem from December 27, 1960, to January 11, 1961. Like the 23rd and 24th Congresses it was held in the National Conventions Building. The ceremonial Inaugural Session was held on Tuesday, December 27, 1960, at 8.45 in the evening in the presence of a large and dis- tinguished gathering, numbering more than three thousand, and in- eluding the President, the Prime Minister, Cabinet Ministers, the Acting Chairman of the Zionist General Council, the Speaker and Deputy- Speakers of the Knesset, the Chief Justice and Judges of the Supreme Court, Rabbi Yitzchak Nissim, the Mayor and City Councillors of Jerusalem, and veteran members of the Zionist Movement. -

Landtagswahl in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern - Was Nu? DR

Baumgarten und die Ajatollahs ISSN 2199-3572 Nr. 9 (25) September 2016/ Av – Elul 5776 RU NDSCHA U 3,70 € JÜDISCHEUNABHÄNGIGE MONATSZEITUNG · H EraUSGEGEBEN VON DR. R. KORENZECHER ver.di und der Eine offene Wunde Die Knesseth Antisemitismus im Körper des feiert jüdischen Volkes Geburtstag Erschreckende Innenansichten Zum 75. Jahrestag Das Parlamentsgebäude aus der Welt der des Massakers des Staates Israel „Intellektuellen“ in Babij Jar wird 50 seite 14-15 seite 9 seite 19 KOLUMNE DES HERAUSGEBERS Landtagswahl in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern - was nu? DR. R. KORENZECHER Liebe Leserinnen und liebe Leser, überschattet von weltweiter, besonders auch in Europa nahezu Alltag gewordener blutiger islamischer Gewalt, von Terror und Gräueltaten des sogennanten Islamischen Staates und von Michal Cizek, AFP Michal blutigen Islam-generierten kriegerischen Aus- einandersetzungen im Mittleren Osten, beson- ders in und um Syrien, geht der Sommer 2016 in dem vor uns liegenden September seinem Ende entgegen. Selbst der völkerverbindende olympische Gedanke, der schon in der Antike das hehre Ziel hatte, die Waffen ruhen und die Jugend nur im friedlichen Wettstreit ihre Kräfte messen zu lassen, musste auch bei der diesjährigen Som- mer-Olympiade von Rio ohne hinreichende Ahndung durch die olympische Völkerfamilie mehrfach Islam-getragenem Judenhass gegen israelische Olympioniken weichen. Gerade angesichts des niemals zu vergessen- den islamischen Mord-Terrors gegen die israe- lische Olympiamannschaft von München 1972 wären nicht nur wie in der politischen Doping- Ahndung gegen Russland eine entschiede- nere Reaktion der Olympia-Verantwortlichen gegenüber den muslimischen Sport-Funkti- onären und ein Ausschluss der islamischen Israel-Diffamierungs-Verbände sicher ein wün- schenswertes, wenn auch versäumtes Signal Von Ramiro Fulano einen Blumenstrauß, weil er seinen Job Gabi freute sich über seine Drei vorm in Richtung einer Aufrechterhaltung der wirkli- nicht verliert – scheitern muss sich wie- Komma (wie beim Abi von der IGS) chen olympischen Idee. -

THE MIDDLE Eash NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961-1963

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY NATIONAL SECURITY FILES THE MIDDLE EASh NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961-1963 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of The John F. Kennedy National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring THE MIDDLE EAST National Security Files, 1961-1963 Microfilmed from the holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Blair Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files. The Middle East [microform]: national security files, 1961-1963. microfilm reels "Microfilmed from the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts; project coordinator, Robert E. Lester." Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick. ISBN 1-55655-013-8 (microfilm) ISBN 1-55655-014-6 (printed guide) 1. Middle East-Politics and government-1945-1979-Sources. 2. Middle East-Foreign relations-United States-Sources. 3. United States-Foreign relations-Middle East-Sources. I. Lester, Robert. II. Hydrick, Blair. III. John F. Kennedy Library. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) [DS63.1.J65 1991] 327.73056-dc20 91-14019 CIP Copyright © 1987 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-014-6. TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction—The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: "Country Files," 1961-1963 v Introduction—The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: Middle East, 1961-1963 ix Scope and Content Note xiii Source Note xv Editorial Note xv Security Classifications xvii Key to Names xix Initialism List xxv Reel Index Reel 1 Afghanistan 1 Cyprus 12 India 17 Reel 2 India conl 24 Iran 29 Israel 49 Reels Israel cont 50 Saudi Arabia 73 United Arab Republic 79 Yemen 85 Author Index 87 Subject Index 91 GENERAL INTRODUCTION The John F. -

Yehuda Amichai

JRB ISRAEL JEWisH REVieW of BOOKS History, Politics, Religion & Culture Edited by Allan Arkush & Abraham Socher JRB ISRAEL JEWisH REVieW of BOOKS History, Politics, Religion & Culture Edited by Allan Arkush Abraham Socher JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly print publication with an active online presence for serious readers with Jewish interests published by Bee.Ideas, LLC. New York, NY Copyright © by Bee.Ideas, LLC. www.jewishreviewofbooks.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Bee.Ideas, LLC. ISBN 13: 978-1-941678-00-8 Contents 5 Introduction 7 Rereading Herzl’s Old-New Land by Shlomo Avineri 13 The Kibbutz and the State by Anita Shapira, translated from the Hebrew by Evelyn Abel 22 Athens or Sparta? by Benny Morris 31 The Poet from Vilna by Ruth R. Wisse 39 Walkers in the City by Stuart Schoffman 47 Moses Mendelssohn Street by Allan Arkush 50 Walking the Green Line by Shmuel Rosner 57 One State? by Peter Berkowitz 61 Fathers & Sons by Yehudah Mirsky 67 Yehuda Amichai: At Play in the Fields of Verse by Robert Alter 75 Israel’s Arab Sholem Aleichem by Alan Mintz 79 Riding Leviathan: A New Wave of Israeli Genre Fiction by Michael Weingrad 87 Hope, Beauty, and Bus Lanes in Tel Aviv by Noah Efron Introduction ere at the Jewish Review of Books our job is to read books, not make them, but we’ve been looking back at the last 18 issues and looking forward—as always, whatever “the matzav”—to celebrating Yom Ha’atzmaut, and we find, to our delight, that we have, more or less (or rather more and less), a book. -

STUDENT El AI

,. \ ". '"'"'\, " .", ~,., ·1 Thursday, July. '10, 1969 Page ;Eight THE' JEWiIS H.P.OST Flight C"US~S Fight 283 Portage Ave~,. ()l;.. ~e- ALIYAH INFORMATION this public seminar may contact Ipany, Jerusalem - A stormy parliamen- , stopPed. making these abominable I Generation Life Assurance Com- phone 942~0651. ., NOTICE TO' HOMEOWNERS' Everyone seriously considering Aulhor Speaker . (,: . tary sesssion ensued here when accusationst a remark for .We· are' prepared to give you the in Israel within the next Thomas C. Hill, author of "The Agudat Yisrael attempte<;i to set off the Speaker. rebuked him. .1 best quality and performance. to Ittrre,e years is invited' to contact the Case for New Life Companies:' 'will a full-dress debate in the Knesset Camel said the. ultra-Orthodox . ! • Tepairs that you may require. Wtie~ ·ther small or big; Painting, concrete Winnipeg branch of the AACA - be the guest speaker at. a public .. over alleged Sabbath desecration by tion was talking hypocrisy and 'walls patching. ,etc. Quality and Association of Americans and Cana- meeting taking place on Wednesday, STUDENT El AI. ing to impose religious satisfaction gUaranteed. dians for Aliyah.·- for information. July 16, at 7. p:ni. at the Interna • GIMPY'S HOME HANDYMAN The executilfe' ~i1I make every effort tional lnn. .Transport~.~~~~~ Minister' Moshe . Camel bathfu~mN~_~HS~-~~C~~~~~i~~---~~~~~~ij~~~~i~~~~ij~f~~~~~------~~~ flight to and ttom Lydda except I WINNIPEG, THURSDAY, JUDY 17, 1969 No. 29 SmVj:CE, FHONE.715-711>9 to as'Sijf;:p;~spective Olim to make Mr. Hill has served as an advisor OPENINGS "8 liar" when the Cabinet official where security is involved or to arrangements or to channel required and consultant to' ov,er 100 life in .