Language in Contact Yesterday—Today—Tomorrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0. Introduction L2/12-386

Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Revised Proposal to Encode Additional Old Italic Characters Source: UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative (Universal Scripts Project) Author: Christopher C. Little ([email protected]) Status: Liaison Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N4046 (L2/11-146R) Date: 2012-11-06 0. Introduction The existing Old Italic character repertoire includes 31 letters and 4 numerals. The Unicode Standard, following the recommendations in the proposal L2/00-140, states that Old Italic is to be used for the encoding of Etruscan, Faliscan, Oscan, Umbrian, North Picene, and South Picene. It also specifically states that Old Italic characters are inappropriate for encoding the languages of ancient Italy north of Etruria (Venetic, Raetic, Lepontic, and Gallic). It is true that the inscriptions of languages north of Etruria exhibit a number of common features, but those features are often exhibited by the other scripts of Italy. Only one of these northern languages, Raetic, requires the addition of any additional characters in order to be fully supported by the Old Italic block. Accordingly, following the addition of this one character, the Unicode Standard should be amended to recommend the encoding of Venetic, Raetic, Lepontic, and Gallic using Old Italic characters. In addition, one additional character is necessary to encode South Picene inscriptions. This proposal is divided into five parts: The first part (§1) identifies the two unencoded characters (Raetic Ɯ and South Picene Ũ) and demonstrates their use in inscriptions. The second part (§2) examines the use of each Old Italic character, as it appears in Etruscan, Faliscan, Oscan, Umbrian, South Picene, Venetic, Raetic, Lepontic, Gallic, and archaic Latin, to demonstrate the unifiability of the northern Italic languages' scripts with Old Italic. -

![Mission: New Guinea]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4485/mission-new-guinea-804485.webp)

Mission: New Guinea]

1 Bibliography 1. L. [Letter]. Annalen van onze lieve vrouw van het heilig hart. 1896; 14: 139-140. Note: [mission: New Guinea]. 2. L., M. [Letter]. Annalen van onze lieve vrouw van het heilig hart. 1891; 9: 139, 142. Note: [mission: Inawi]. 3. L., M. [Letter]. Annalen van onze lieve vrouw van het heilig hart. 1891; 9: 203. Note: [mission: Inawi]. 4. L., M. [Letter]. Annalen van onze lieve vrouw van het heilig hart. 1891; 9: 345, 348, 359-363. Note: [mission: Inawi]. 5. La Fontaine, Jean. Descent in New Guinea: An Africanist View. In: Goody, Jack, Editor. The Character of Kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1973: 35-51. Note: [from lit: Kuma, Bena Bena, Chimbu, Siane, Daribi]. 6. Laade, Wolfgang. Der Jahresablauf auf den Inseln der Torrestraße. Anthropos. 1971; 66: 936-938. Note: [fw: Saibai, Dauan, Boigu]. 7. Laade, Wolfgang. Ethnographic Notes on the Murray Islanders, Torres Strait. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 1969; 94: 33-46. Note: [fw 1963-1965 (2 1/2 mos): Mer]. 8. Laade, Wolfgang. Examples of the Language of Saibai Island, Torres Straits. Anthropos. 1970; 65: 271-277. Note: [fw 1963-1965: Saibai]. 9. Laade, Wolfgang. Further Material on Kuiam, Legendary Hero of Mabuiag, Torres Strait Islands. Ethnos. 1969; 34: 70-96. Note: [fw: Mabuiag]. 10. Laade, Wolfgang. The Islands of Torres Strait. Bulletin of the International Committee on Urgent Anthropological and Ethnological Research. 1966; 8: 111-114. Note: [fw 1963-1965: Saibai, Dauan, Boigu]. 11. Laade, Wolfgang. Namen und Gebrauch einiger Seemuscheln und -schnecken auf den Murray Islands. Tribus. 1969; 18: 111-123. Note: [fw: Murray Is]. -

Culture E Studi Del Sociale Cussoc ISSN: 2531-3975

Culture e Studi del Sociale CuSSoc ISSN: 2531-3975 Movement to Another Place. Cultural Expressions of Migration as Source of Reflection Contributing to Social Theory PAICH SLOBODAN DAN Come citare / How to cite Paich, S.D. (2017). Movement to Another Place. Cultural Expressions of Migration as Source of Ref- lection Contributing to Social Theory. Culture e Studi del Sociale, 2(2), 129-141. Disponibile / Retrieved from http://www.cussoc.it/index.php/journal/issue/archive 1. Affiliazione Autore / Authors’ information The Artship Foundation, San Francisco-USA 2. Contatti / Authors’ contact Slobodan Dan Paich: [email protected] Articolo pubblicato online / Article first published online: Dicembre/December 2017 - Peer Reviewed Journal Informazioni aggiuntive / Additional information Culture e Studi del Sociale Movement to Another Place. Cultural Expressions of Migration as Source of Reflection Contributing to Social Theory Slobodan Dan Paich The Artship Foundation – San Francisco, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Methodologies are explored to enriching migration theory, with an inter-disciplinary look into cultural expressions resulting from migration. Cultural and migration maps offer a comparative and diachronic insight into migration impulses and waves.Migration of ideas and techniques is also examined through artifacts resulting from forced or intended move- ment of people and experts. Two contemporary plays evolved from the stories of mi- grants/refugees offer probing and open-ended speculation about itinerancy, vagrancy, reset- tlement and economic emigration as part of social plurality. The tangible, visceral qualities of expression may shed light on issues too complex for verbal theory only. Approached is comparative examination of stylization in art and abstraction in theoretical inquiry. -

Languages in Sicily Between the Classical Age and Late Antiquity: a Case of Punctuated Equilibrium? Marta Capano (Università Degli Studi Di Napoli L’Orientale)

Languages in Sicily between the Classical Age and Late Antiquity: a case of punctuated equilibrium? Marta Capano (Università degli Studi di Napoli L’Orientale) Abstract Although late Roman Sicily is clearly represented by the ancient authors as a multilingual environment, the 20th–century scientific debate has proposed two divergent descriptions of the Sicilian linguistic landscape. While some scholars denied a deep Latinization under the Roman Empire, the increasing evidence of Latin inscriptions led others to hypothesize the decline of Greek. In the last decades, new approaches to bilingualism and linguistic contact, applied to antiquity, have demonstrated that many languages frequently coexist for a long time. Multilingualism has always characterized Sicily, but, before the Roman conquest, all minority languages had gradually disappeared, and the diatopic and dialectal variation of Greek converged towards a slightly Doric κοινά. As we can see from the epigraphic evidence, Roman Sicily was fully Greek–Latin bilingual until the end of the 5th century, and the two languages influenced each other. Latin and Greek epigraphs show similar onomastic material and phonological and morphological features, as well as a number of shared set phrases (mostly from Latin). These data are consistent with the first phase of Dixon’s theory of “punctuated equilibrium”, namely the equilibrium, since the two populations had a similar population, lifestyle and religious beliefs and, although Romans ruled over Sicily, Greek language and culture never lost their prestige. Even though the quantity of Greek evidence is not stable over the course of the 5th century, Sicily ultimately displays a situation of equilibrium until the end of the 5th century. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

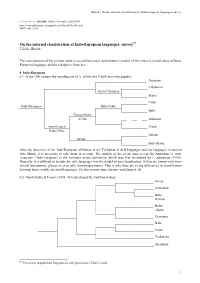

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3. -

Encountering Environments

ENCOUNTERING ENVIRONMENTS ENCOUNTERING ENCOUNTERING ENVIRONMENTS Natural conditions for subsistence and trade at Monte Polizzo, Sicily 650-550 BC Cecilia Sandström Cecilia Sandström ENCOUNTERING ENVIRONMENTS ENCOUNTERING ENVIRONMENTS Natural conditions for subsistence and trade at Monte Polizzo, Sicily 650-550 BC Cecilia Sandström Doctoral dissertation in Classical archaeology and Ancient history, University of Gothenburg 20210924 © Cecilia Sandström, 2021 Cover Photo: Cecilia Sandström Printed by: Kompendiet, Göteborg 2021 isbn: 978-91-8009-406-1 (print) isbn: 978-91-8009-407-8 (pdf) Distribution: Historiska institutionen Göteborgs universitet Box 200 SE-405 30 Göteborg To my beloved mother in memoriam, and to my wonderful daughter – the light of my life Map of Sicily. Showing indigenous, Phoenician and Greek settlements mentioned in this thesis. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the following founda- however, with a work-life balance in disequilibrium, tions for their generous support during the course you literally scared me into start writing after a time of this work: of non-activity. I had received the SIR fellow in Ar- Helge Ax:son Johnsons Stiftelse, Stiftelsen Enboms chaeology in 2018, when you ordered me to set up donationsfond, Stiftelsen Ingrid och Torsten Gihls a Gantt chart. There is no other way for you to get fond för Svenska Institutet i Rom, Johan och Jakob this work done, you said. I was reluctant I admit Söderbergs Stiftelse, Fondazione Famiglia Rausing, it. I had nightmares about Gantt charts. I realised Adlerbertska Stipendiestiftelsen, and Svenska Insti- though, that structure – as well as holistic balance- is tutet i Rom. truly essential. You have constantly encouraged me to improve. -

Taraka Rama Studies in Computational Historical Linguistics

i “slut_seminar_thesis” — 2015/5/7 — 17:04 — page 1 — #1 i i i Taraka Rama Studies in computational historical linguistics i i i i i “slut_seminar_thesis” — 2015/5/7 — 17:04 — page 2 — #2 i i i Data linguistica <http://www.svenska.gu.se/publikationer/data-linguistica/> Editor: Lars Borin Språkbanken Department of Swedish University of Gothenburg 27 • 2015 i i i i i “slut_seminar_thesis” — 2015/5/7 — 17:04 — page 3 — #3 i i i Taraka Rama Studies in computational historical linguistics Models and analysis Gothenburg 2015 i i i i i “slut_seminar_thesis” — 2015/5/7 — 17:04 — page 4 — #4 i i i Data linguistica 27 ISBN ISSN 0347-948X Printed in Sweden by Reprocentralen, Campusservice Lorensberg, University of Gothenburg 2015 Typeset in LATEX 2e by the author Cover design by Kjell Edgren, Informat.se Front cover illustration: Author photo on back cover by Kristina Holmlid i i i i i “slut_seminar_thesis” — 2015/5/7 — 17:04 — page i — #5 i i i ABSTRACT Computational analysis of historical and typological data has made great progress in the last fifteen years. In this thesis, we work with vocabulary lists for ad- dressing some classical problems in historical linguistics such as discriminat- ing related languages from unrelated languages, assigning possible dates to splits in a language family, employing structural similarity for language clas- sification, and providing an internal structure to a language family. In this thesis, we compare the internal structure inferred from vocabulary lists with the family trees inferred given in Ethnologue. We also explore the ranking of lexical items in the widely used Swadesh word list and compare our ranking to another quantitative reranking method and short word lists com- posed for discovering long-distance genetic relationships. -

Contatti Di Scritture Multilinguismo E Multigrafismo Dal Vicino

Filologie medievali e moderne 9 Serie occidentale 8 — Contatti di lingue - Contatti di scritture Multilinguismo e multigrafismo dal Vicino Oriente Antico alla Cina contemporanea a cura di Daniele Baglioni, Olga Tribulato Edizioni Ca’Foscari Contatti di lingue - Contatti di scritture Filologie medievali e moderne Serie occidentale Serie diretta da Eugenio Burgio 9 | 7 Edizioni Ca’Foscari Filologie medievali e moderne Serie occidentale Direttore Eugenio Burgio (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Comitato scientifico Massimiliano Bampi (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Saverio Bellomo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Marina Buzzoni (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Serena Fornasiero (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Lorenzo Tomasin (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Tiziano Zanato (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Serie orientale Direttore Antonella Ghersetti (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Comitato scientifico Attilio Andreini (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Giampiero Bellingeri (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Paolo Calvetti (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Marco Ceresa (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Daniela Meneghini (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Antonio Rigopoulos (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Bonaventura Ruperti (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) http://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/col/exp/36/FilologieMedievali Contatti di lingue - Contatti di scritture Multilinguismo e multigrafismo dal Vicino Oriente Antico alla Cina -

Tri-Nodal Social Entanglements in Iron Age Sicily: Material and Social Transformation

Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology Volume 3 Article 4 2012 Tri-Nodal Social Entanglements in Iron Age Sicily: Material and Social Transformation William Balco Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldnotes Recommended Citation Balco, William (2012) "Tri-Nodal Social Entanglements in Iron Age Sicily: Material and Social Transformation," Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology: Vol. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldnotes/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tri-Nodal Social Entanglements in Iron Age Sicily: Material and Social Transformation William Balco Abstract: Indigenous Iron Age Sicilian populations underwent a series of complex social transformations following the establishment of neighboring Greek and Phoenician trade posts in the eighth through fifth centuries BC. This paper employs the theory of cultural hybridity to explore indigenous Iron Age Elymian responses to the socially entangled atmosphere. Prolonged contact and interaction with foreigners fostered numerous alterations to Elymian pottery, architecture, and language. Such archaeologically visible changes are discussed, accounting for the development of a complex social middle ground encompassing the Elymi, Greeks, and Phoenicians. Additionally, this paper offers an agenda for future research focusing on the development of mixed-style material culture within complex social entanglements. Key words: Cultural Hybridity, Sicily, Elymi, Iron Age, Social Transformation Social Interaction Theory Sophisticated contact and interaction between different populations remains the object of intense research and debate among contemporary social theorists. -

Advances in the Study of Siouan Languages and Linguistics

Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics Edited by Catherine Rudin Bryan J. Gordon language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 10 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath Consulting Editors: Fernando Zúñiga, Peter Arkadiev, Ruth Singer, Pilar Valen zuela In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. ISSN: 2363-5568 Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics Edited by Catherine Rudin Bryan J. Gordon language science press Catherine Rudin & Bryan J. Gordon (eds.). 2016. Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics (Studies in Diversity Linguistics 10). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/94 © 2016, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-946234-37-1 (Digital) 978-3-946234-38-8 (Hardcover) 978-3-946234-39-5 (Softcover) -

Kodikologie Und Paläographie Im Digitalen Zeitalter 4

Schriften des Instituts für Dokumentologie und Editorik — Band11 Kodikologie und Paläographie im digitalen Zeitalter 4 Codicology and Palaeography in the Digital Age 4 herausgegeben von | edited by Hannah Busch, Franz Fischer, Patrick Sahle unter Mitarbeit von | in collaboration with Bernhard Assmann, Philipp Hegel, Celia Krause 2017 BoD, Norderstedt Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de/ abrufbar. Diese Publikation wurde im Rahmen des Projektes eCodicology (Förderkennzeichen 01UG1350A-C) mit Mitteln des Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) gefördert. Publication realised within the project eCodicology (funding code 01UG1350A-C) with financial resources of the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF). 2017 Herstellung und Verlag: Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt ISBN: 978-3-7448-3877-1 Einbandgestaltung: Julia Sorouri, basierend auf Vorarbeiten von Johanna Puhl und Katharina Weber; Coverbild nach einer Vorlage von Swati Chandna. Satz: LuaTEX und Bernhard Assmann Phenetic Approach to Script Evolution Gábor Hosszú Abstract Computational palaeography, as a branch of applied computer science, investigates the evolution of graphemes, explores relationships between scripts, and provides support for deciphering ancient inscriptions, among others. The author applied methods often used to describe evolutionary processes in phylogenetics to analyse the development of scripts. Unlike in the clear evolution of phylogenetics, graphemes used to describe the evolution of scripts are sometimes indistinguishable from their glyph variants. Moreover, the historical background is at times incomplete. In order to reduce uncertainty, the author developed an exploratory data analysis method that combines phenetic analysis methods with a cladistic approach.