Canoe Nation Nature, Race, and the Making of a Canadian Icon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sleeping Giant (2007)

The Sleeping Giant (2007) For orchestra By Abigail Richardson Duration: 5 minutes. 2222 4231 timpani +2, strings Percussion I: Crotales, Glockenspiel, Slapstick, Thundersheet Percussion II: Feng Luo, North American Tom Tom (or appropriate substitute), Bass Drum, Triangle, Suspended Cymbal After CBC's recent "Seven Wonders of Canada" competition, I was quite taken with the support of the Thunder Bay community for the Sleeping Giant. I decided to write this piece for the legend. Here is the story: Nanabosho the giant and son of the West wind was a hero to the Ojibwe tribe for saving them from the Sioux. One day he scratched a rock and discovered silver. Nanabosho knew the white men would take over the land for this silver so he swore his tribe to secrecy and buried the silver. One of the chieftains decided to make himself silver weapons and was soon after killed by the Sioux. He must have passed along the silver secret as several days later a Sioux warrior was spotted in a canoe leading two white men towards the silver. Nanabosho disobeyed the Great Spirit and raised a storm which killed the men. As punishment he was turned to stone and lies watching over his silver secret. Abigail Richardson was born in Oxford, England and moved to Canada as a child. Ironically, she was diagnosed completely and incurably deaf at the age of five. Upon moving to Canada, her hearing was fully intact within months. She received her Bachelor of Music from the University of Calgary and her Masters and Doctorate degrees from the University of Toronto. -

Paul Heintzman University of Ottawa Conference Travel Funded by The

The Ecological Virtues of Bill Mason Paul Heintzman University of Ottawa Conference Travel Funded by the Reid Trust Introduction ■ Although much has been written in the last few decades about ecological virtue ethics, very little has been written on this topic from a Christian perspective (Bouma-Prediger, 2016; Blanchard & O’Brien, 2014; Melin, 2013). ■ Virtue Ethics: What type of person should I be? ■ Cultivation of certain virtues are necessary to address ecological problems (Bouma-Prediger, 2016) ■ Sometimes we see practices embodied in a person who displays what a life of virtue concretely looks like (Bouma-Prediger, 2016) ■ E.g., Mother Teresa ■ “Such people are ethical exemplars or models of virtue who inspire us to live such a life ourselves.” (Bouma-Prediger, 2016, p. 24) ■ Doesn’t give an example ■ This paper explores whether Bill Mason is an Christian exemplar of ecological virtues Bill Mason: Canoeist, Filmmaker, Artist 1929-1988 Mason Films (most National Film Board of Canada films) ■ Wilderness Treasure ■ Paddle to the Sea ■ Rise and Fall of the Great Lakes ■ Blake ■ Death of a Legend ■ Wolf Pack ■ In Search of the Bowhead Whale ■ Cry of the Wild ■ Face of the Earth ■ Path of the Paddle Series (4 films) ■ Song of the Paddle ■ Coming Back Alive ■ Pukaskwa National Park ■ Where the Buoys Are ■ The Land That Devours Ships ■ Waterwalker Ongoing Influence ■ Postage Stamp ■ 2009: Inducted posthumously into the International Whitewater Hall of Fame Writings on Mason: ■ Biography ■ Raffan (1995). Fire in the bones. ■ Canoeing ■ Raffan (1999). Being there: Bill Mason and the Canadian canoeing tradition. ■ Art ■ Buck (2005). Bill Mason: Wilderness artist from heart to hand. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

Bill Mason Bill Mason Bill Mason Canadian Canoeing to Capture a Shot, Mason Would Often Invent Ways to Legend Get the Camera Into Position

Bill Mason Bill Mason Bill Mason Canadian Canoeing To capture a shot, Mason would often invent ways to Legend get the camera into position. This homemade raft and waterproof case allowed the camera to float while A Life on the Water Bill Mason was passionate about telling a story through Mason filmed himself after capsizing in rapids. film. He often used this camera, Born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Mason (1929-1988) first taking the shot again and again to get it right. Pour prendre des vues, Mason inventait souvent des worked as a commercial artist and canoe instructor. moyens de mettre la caméra en position. Ce radeau Bill Mason avait une passion pour le cinéma comme artisanal et cet étui imperméable permettaient à After moving to the Ottawa region in 1958, Mason began moyen de raconter une histoire. Il a souvent utilisé cette la caméra de flotter pendant que Mason se filmait après caméra, une , et répétait les prises his career as a filmmaker. Working on camera and behind it, avoir chaviré dans des rapides. de vues jusqu’à ce qu’il obtienne exactement ce qu’il voulait. One of his earliest films was Paddle to the Sea (1966), a project for the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) Bill Mason was an iconic Canadian filmmaker that was nominated for an Academy Award in 1968. His other NFB films were also highly acclaimed, notably Bill Mason loved the outdoors and had a keen eye the Path of the Paddle series (1977), which teaches the in more ways than one. His canoeing and for the effects of light on a scene. -

Bill Mason and the Canadian Canoeing Tradition Review

When Bill Mason set off alone into the wilderness in his red canoe, many people went with him, if only in their imaginations. Now, James Raffan leads us into the heart of the vast landscape that was Bill Mason's own brilliant imagination, on a biographical journey that is entertaining, enriching and inspiring.Bill Mason was a filmmaker who gave us classics such as Cry of the Wild and Paddle to the Sea he was author of the canoeist's bible, Path of the Paddle he was the consummate outdoorsman. But few Canadians know that his gentleness and rugged self-sufficiency masked a life of great physical struggles. James Raffan reveals the private, sometimes anguished, man behind the legend. [Doc] Fire in the Bones: Bill Mason and the Canadian Canoeing Tradition Full version Get : https://seeyounexttime22.blogspot.com/?book=0006386555 When Bill Mason set off alone into the wilderness in his red canoe, many people went with him, if only in their imaginations. Now, James Raffan leads us into the heart of the vast landscape that was Bill Mason's own brilliant imagination, on a biographical journey that is entertaining, enriching and inspiring.Bill Mason was a filmmaker who gave us classics such as Cry of the Wild and Paddle to the Sea he was author of the canoeist's bible, Path of the Paddle he was the consummate outdoorsman. But few Canadians know that his gentleness and rugged self-sufficiency masked a life of great physical struggles. James Raffan reveals the private, sometimes anguished, man behind the legend. Full version Fire in the Bones: Bill Mason and the Canadian Canoeing Tradition Review Description When Bill Mason set off alone into the wilderness in his red canoe, many people went with him, if only in their imaginations. -

Beck Mason Interview, Final Copy

-The Becky Mason Interview- April 2013 The Canadian Canoe Foundation was very fortunate to recently interview one of our Canadian canoeing heroes, Becky Mason. Becky comes by her love of paddling and painting honestly. She is the highly accomplished daughter of Bill Mason, Canada’s most beloved canoeist, who also achieved great success as a commercial artist, animator, filmmaker, author and painter. Becky lives in Chelsea Quebec, and her lifestyle and art are steeped in the singular beauty of that area. We asked Becky a few questions about her art, her love of the canoe, and her thoughts on what the Canadian Canoe Foundation is doing to educate youth about the importance of our Canadian Watersheds. CCF- You are seen as a modern ambassador for canoeing, and your passion for classic solo canoeing has taken you far and wide for speaking engagements and paddling workshops. Tell us about your exciting Spring Tour of 2010, and where it took you. Becky- Our 2010 UK Tour took my husband Reid and I to Scotland, Ireland and England for 5 weeks with a final week in Sweden. It was a fabulous experience and we spent our time teaching, doing demonstrations and giving talks on canoeing. This trip really made us aware of how international "Canadian" canoeing has become and that we have the same passion for paddling as our friends across the ocean and can share our knowledge with them and vice versa. We were so enthralled with our trip that the next year, as soon as I had finished editing my Advanced Classic Solo Canoeing DVD we went back, this time to continental Europe, and did a tour of the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and then England again. -

The CBC's "Seven Wonders of Canada" : Exclusionary Aspects of A

\ ^ s ? 1 § v THE CBC'S "SEVEN WONDERS OF CANADA": EXCLUSIONARY ASPECTS OF A PROJECT OF NATIONAL IDENTITY ^ ^ A i^T J By Debbie Starzynski, BA, University of New Hampshire, 1973 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Immigration and Settlement Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2009 Debbie Starzynski 2009 PROPERTY OF RYERSON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY r Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this major research paper. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this paper by photocopying or by other means, in total or part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature 11 THE CBC'S "SEVEN WONDERS OF CANADA: EXCLUSIONARY ASPECTS OF A PROJECT OF NATIONAL IDENTITY A major research paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in Immigration and Settlement Studies, Ryerson University, 2009 By Debbie Starzynski ji ABSTRACT The topic of my major research paper is national identity in the context of cultural pluralism. The paper has as its goal a socio-cultural analysis of national belonging. Immigration policy as gateway has, historically, excluded certain groups from entry to the country; nationalisms have prevented some of those who have gained entry to the country from gaining entry to the nation. I argue that the CBC's "Seven Wonders of Canada" campaign is one such nationalism, revealing nationalist tropes which include the cultural centre's longstanding tradition of identifying with the landscape and its more recent tradition of identifying with multicultural ideology - in its construction of national identity. -

Negotiating with Oral Histories at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

Negotiating with Oral Histories at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Ashley Clarkson A Thesis in The Department Of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada January 2015 © Ashley Clarkson, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Ashley Clarkson Entitled: Negotiating with Oral Histories at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) Complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Shannon McSheffrey Chair Elena Razlogova Examiner Erica Lehrer Examiner Steven High Supervisor Approved by: Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director Dean of Faculty Abstract This thesis explores the transition of Pier 21 from a local heritage group to its designation as a national museum in 2009. How it is balancing its role as national historic site, with a large source community, and its mandate to represent the national history of Canadian immigration. The emphasis on intangible cultural heritage, or people’s recorded stories, rather than material artifacts, places Pier 21 in the position to adopt new technologies and to connect on-and offline interpretation. In the beginning Pier 21 brought together a community of immigrants and it was oral histories that helped activate that community in order to bring the institution to life. When Pier 21 is referred to as the ‘museum of memories,’ it invokes not only the memories rooted in the exhibits but in the memories that permeate the site itself. -

Nfb Film Club Program

NFB FILM CLUB PROGRAM FALL 2017 A TURN-KEY INITIATIVE CREATED SPECIFICALLY FOR PUBLIC LIBRARIES, THE NFB FILM CLUB GRANTS FREE, PRIVILEGED ACCESS TO NEW, RELEVANT, AND THOUGHT-PROVOKING DOCUMENTARIES AS WELL AS AWARD-WINNING AND ENTERTAINING ANIMATION FOR THE WHOLE FAMILY. CONTACT Marianne Di Domenico 514-283-8953 | [email protected] PROGRAM A MARKING CANADA’S 150TH ANNIVERSARY LOG DRIVER’S WALTZ WATERWALKER 3 MIN 28 S 86 MIN 38 S A young girl who loves to dance and is ready to marry chooses Follow naturalist Bill Mason on his journey by canoe into the a log driver over his more well-to-do, land-loving competition. Ontario wilderness. The filmmaker begins on Lake Superior, Driving logs down the river has made him the best dancing then explores winding and sometimes tortuous river waters to partner around. This lighthearted, animated tale is based on the meadowlands of the river’s source. Along the way, Mason Wade Hemsworth’s song “The Log Driver’s Waltz,” sung by Kate muses about his love of the canoe, his artwork and his own and Anna McGarrigle to the music of the Mountain City Four. relationship to the land. Features breathtaking visuals and a musical score by one of Canada’s most renowned musicians, Bruce Cockburn. PROGRAM B MARKING CANADA’S 150TH ANNIVERSARY (TOTAL RUNTIME: 89 MIN) BIG DRIVE GONE CURLING 9 MIN 15 S 10 MIN 13 S From Anita Lebeau, director of the award-winning film Louise, Hockey has its fans, but on the Canadian prairies curling is comes the story of a family road trip across the Canadian prai- almost a cult. -

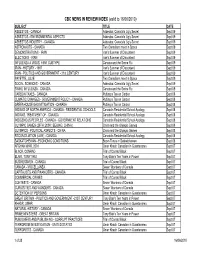

CBC NEWS in REVIEW INDEX (Valid to 16/06/2010)

CBC NEWS IN REVIEW INDEX (valid to 16/06/2010) SUBJECT TITLE DATE ASBESTOS - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASBESTOS - ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASBESTOS INDUSTRY - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASTRONAUTS - CANADA Two Canadians meet in Space Sept.09 DEMONSTRATIONS - IRAN Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 ELECTIONS - IRAN Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 INFLUENZA A VIRUS, H5N1 SUBTYPE Canada and the Swine Flu Sept.09 IRAN - HISTORY - 1997 Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 IRAN - POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT - 21st CENTURY Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 PAYETTE, JULIE Two Canadians meet in Space Sept.09 SOCIAL SCIENCES - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 SWINE INFLUENZA - CANADA Canada and the Swine Flu Sept.09 CARBON TAXES - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 CLIMATIC CHANGES - GOVERNMENT POLICY - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 GREENHOUSE GAS MITIGATION - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 INDIANS OF NORTH AMERICA - CANADA - RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 INDIANS, TREATMENT OF - CANADA Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES - CANADA - GOVERNMENT RELATIONS Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 OLYMPIC GAMES (29TH :2008 : BEIJING, CHINA) China and the Olympic Games Sept.08 OLYMPICS - POLITICAL ASPECTS - CHINA China and the Olympic Games Sept.08 RECONCILIATION (LAW) - CANADA Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 SASKATCHEWAN - ECONOMIC CONDITIONS Boom Times in Saskatchewan -

Canoe Pedagogy and Colonial History: Exploring Contested Spaces of Outdoor Environmental Education

Canoe Pedagogy and Colonial History: Exploring Contested Spaces of Outdoor Environmental Education Liz Newbery, University of Toronto, Canada Abstract In this paper, I explore how histories of colonialism are integral to the Euro-Western idea of wilderness at the heart of much outdoor environmental education. In the context of canoe tripping, I speculate about why the politics of land rarely enters into teaching on the land. Finally, because learning from difficult knowledge often troubles the learner, I consider the pedagogical value of emotional responses to curricula that address colonial implication. Résumé Dans le présent article, je me penche sur la mesure dans laquelle l’histoire du colonialisme fait partie intégrante de la conception occidentale de la nature sauvage au sein de programmes d’éducation environnementale intensive. Dans un contexte d’excursions en canot, je spécule sur l’omission fréquente des politiques territoriales dans l’enseignement environnemental. Enfin, puisque l’apprentissage à partir de connaissances complexes peut déconcerter l’élève, j’examine la valeur pédagogique de la réaction émotive dans les programmes d’enseignement se penchant sur le facteur colonial. Keywords: wilderness, colonialism, difficult knowledge, canoe trip, outdoor environmental education, Canada Part of the work of environmental education must be to confront the traumatic traces lingering in a nation born through colonization. For years as an environ- mental educator working in a primarily canoe trip based context, I put an emphasis on the land, tried to slow down and be quiet enough for students to develop a sense of place, a respect for this more-than-human world. But the trickiness of the place—the contested histories of space, the ambivalent role that the canoe played in Canada’s origins, the very context for all of this learning— tended to go unacknowledged in my pedagogies. -

2012 World Holstein Conference Unifies Dairy Industry in Canada

infoHolstein infoHolsteinDecember/January 2013 issue no. 119 A Holstein Canada publication providing informative, challenging, and topical news. Remembering the Event of a Lifetime: 2012 World Holstein Conference Unifies Dairy Industry in Canada & Abroad Thank You! The conclusion of the 2012 World Holstein Conference bringsMerci! a multitude of sincere thanks to all those who made the Conference a success! Thank you to Holstein Canada members who shared in this momentous event and to the following host farms who opened their doors to Conference participants: La fin du Congrès mondial Holstein 2012 suscite une multitude de sincères remerciements à l’intention de tous ceux et celles qui ont fait du Congrès un succès! Merci aux membres de Holstein Canada qui ont partagé cet événement historique et aux fermes hôtes suivantes qui ont ouvert leurs portes aux participants au Congrès : Altona Lea Farms Gillette Armstrong Manor J & L Walker Dairy Astonic La Présentation Bosdale Maple Keys Cityview Mapel Wood Claynook Quality Cranholme Stantons Fradon Summitholm Gen-Com Wikkerink World Level Sponsors / Commanditaires du niveau monde infoHolstein December/January 2013 12 Thank You! No. 119 EditorHolstein Christina Crowley infoChief Executive Ann Louise Carson The conclusion of the 2012 World Holstein Conference bringsMerci! a multitude of sincere Officer thanks to all those who made the Conference a success! Thank you to Holstein Canada Board of Directors members who shared in this momentous event and to the following host farms who President Glen