Canoe Pedagogy and Colonial History: Exploring Contested Spaces of Outdoor Environmental Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sleeping Giant (2007)

The Sleeping Giant (2007) For orchestra By Abigail Richardson Duration: 5 minutes. 2222 4231 timpani +2, strings Percussion I: Crotales, Glockenspiel, Slapstick, Thundersheet Percussion II: Feng Luo, North American Tom Tom (or appropriate substitute), Bass Drum, Triangle, Suspended Cymbal After CBC's recent "Seven Wonders of Canada" competition, I was quite taken with the support of the Thunder Bay community for the Sleeping Giant. I decided to write this piece for the legend. Here is the story: Nanabosho the giant and son of the West wind was a hero to the Ojibwe tribe for saving them from the Sioux. One day he scratched a rock and discovered silver. Nanabosho knew the white men would take over the land for this silver so he swore his tribe to secrecy and buried the silver. One of the chieftains decided to make himself silver weapons and was soon after killed by the Sioux. He must have passed along the silver secret as several days later a Sioux warrior was spotted in a canoe leading two white men towards the silver. Nanabosho disobeyed the Great Spirit and raised a storm which killed the men. As punishment he was turned to stone and lies watching over his silver secret. Abigail Richardson was born in Oxford, England and moved to Canada as a child. Ironically, she was diagnosed completely and incurably deaf at the age of five. Upon moving to Canada, her hearing was fully intact within months. She received her Bachelor of Music from the University of Calgary and her Masters and Doctorate degrees from the University of Toronto. -

The CBC's "Seven Wonders of Canada" : Exclusionary Aspects of A

\ ^ s ? 1 § v THE CBC'S "SEVEN WONDERS OF CANADA": EXCLUSIONARY ASPECTS OF A PROJECT OF NATIONAL IDENTITY ^ ^ A i^T J By Debbie Starzynski, BA, University of New Hampshire, 1973 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Immigration and Settlement Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2009 Debbie Starzynski 2009 PROPERTY OF RYERSON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY r Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this major research paper. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this paper by photocopying or by other means, in total or part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature 11 THE CBC'S "SEVEN WONDERS OF CANADA: EXCLUSIONARY ASPECTS OF A PROJECT OF NATIONAL IDENTITY A major research paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in Immigration and Settlement Studies, Ryerson University, 2009 By Debbie Starzynski ji ABSTRACT The topic of my major research paper is national identity in the context of cultural pluralism. The paper has as its goal a socio-cultural analysis of national belonging. Immigration policy as gateway has, historically, excluded certain groups from entry to the country; nationalisms have prevented some of those who have gained entry to the country from gaining entry to the nation. I argue that the CBC's "Seven Wonders of Canada" campaign is one such nationalism, revealing nationalist tropes which include the cultural centre's longstanding tradition of identifying with the landscape and its more recent tradition of identifying with multicultural ideology - in its construction of national identity. -

Negotiating with Oral Histories at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

Negotiating with Oral Histories at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Ashley Clarkson A Thesis in The Department Of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada January 2015 © Ashley Clarkson, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Ashley Clarkson Entitled: Negotiating with Oral Histories at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) Complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Shannon McSheffrey Chair Elena Razlogova Examiner Erica Lehrer Examiner Steven High Supervisor Approved by: Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director Dean of Faculty Abstract This thesis explores the transition of Pier 21 from a local heritage group to its designation as a national museum in 2009. How it is balancing its role as national historic site, with a large source community, and its mandate to represent the national history of Canadian immigration. The emphasis on intangible cultural heritage, or people’s recorded stories, rather than material artifacts, places Pier 21 in the position to adopt new technologies and to connect on-and offline interpretation. In the beginning Pier 21 brought together a community of immigrants and it was oral histories that helped activate that community in order to bring the institution to life. When Pier 21 is referred to as the ‘museum of memories,’ it invokes not only the memories rooted in the exhibits but in the memories that permeate the site itself. -

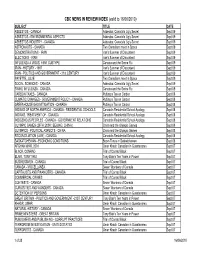

CBC NEWS in REVIEW INDEX (Valid to 16/06/2010)

CBC NEWS IN REVIEW INDEX (valid to 16/06/2010) SUBJECT TITLE DATE ASBESTOS - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASBESTOS - ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASBESTOS INDUSTRY - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASTRONAUTS - CANADA Two Canadians meet in Space Sept.09 DEMONSTRATIONS - IRAN Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 ELECTIONS - IRAN Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 INFLUENZA A VIRUS, H5N1 SUBTYPE Canada and the Swine Flu Sept.09 IRAN - HISTORY - 1997 Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 IRAN - POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT - 21st CENTURY Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 PAYETTE, JULIE Two Canadians meet in Space Sept.09 SOCIAL SCIENCES - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 SWINE INFLUENZA - CANADA Canada and the Swine Flu Sept.09 CARBON TAXES - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 CLIMATIC CHANGES - GOVERNMENT POLICY - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 GREENHOUSE GAS MITIGATION - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 INDIANS OF NORTH AMERICA - CANADA - RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 INDIANS, TREATMENT OF - CANADA Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES - CANADA - GOVERNMENT RELATIONS Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 OLYMPIC GAMES (29TH :2008 : BEIJING, CHINA) China and the Olympic Games Sept.08 OLYMPICS - POLITICAL ASPECTS - CHINA China and the Olympic Games Sept.08 RECONCILIATION (LAW) - CANADA Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 SASKATCHEWAN - ECONOMIC CONDITIONS Boom Times in Saskatchewan -

2012 World Holstein Conference Unifies Dairy Industry in Canada

infoHolstein infoHolsteinDecember/January 2013 issue no. 119 A Holstein Canada publication providing informative, challenging, and topical news. Remembering the Event of a Lifetime: 2012 World Holstein Conference Unifies Dairy Industry in Canada & Abroad Thank You! The conclusion of the 2012 World Holstein Conference bringsMerci! a multitude of sincere thanks to all those who made the Conference a success! Thank you to Holstein Canada members who shared in this momentous event and to the following host farms who opened their doors to Conference participants: La fin du Congrès mondial Holstein 2012 suscite une multitude de sincères remerciements à l’intention de tous ceux et celles qui ont fait du Congrès un succès! Merci aux membres de Holstein Canada qui ont partagé cet événement historique et aux fermes hôtes suivantes qui ont ouvert leurs portes aux participants au Congrès : Altona Lea Farms Gillette Armstrong Manor J & L Walker Dairy Astonic La Présentation Bosdale Maple Keys Cityview Mapel Wood Claynook Quality Cranholme Stantons Fradon Summitholm Gen-Com Wikkerink World Level Sponsors / Commanditaires du niveau monde infoHolstein December/January 2013 12 Thank You! No. 119 EditorHolstein Christina Crowley infoChief Executive Ann Louise Carson The conclusion of the 2012 World Holstein Conference bringsMerci! a multitude of sincere Officer thanks to all those who made the Conference a success! Thank you to Holstein Canada Board of Directors members who shared in this momentous event and to the following host farms who President Glen -

Zone Analysis Branch

Taltson Hydroelectric Expansion Project TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 21. REFERENCES................................................................................................21.1 Chapter 2. Regulatory Process ...................................................................................................................... 21.1 Chapter 4. Community Engagement.............................................................................................................. 21.1 Chapter 5. Purpose and Rationale................................................................................................................. 21.1 Chapter 6. Development Description............................................................................................................. 21.1 Chapter 8. Alternatives ................................................................................................................................... 21.1 Chapter 9. Existing Environment................................................................................................................... 21.1 SECTION 9.1. LOCATION ...................................................................................................................... 21.1 SECTION 9.2. AREAS OF SPECIAL SENSITIVITY...................................................................................... 21.2 SECTION 9.3. TALTSON BASIN HYDROLOGY.......................................................................................... 21.2 SECTION 9.4. PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................... -

Rockwalls and Waterfalls

Rockwalls and Waterfalls Volume # 45 Summer 2010 Saluting our past; celebrating our future 125 years of national parks in Canada ne-hundred and twenty five years is a mere blink of the eye in geologic terms – it can take many millions of Oyears to form mountains as majestic and well-chiselled as our very own Canadian Rockies. Thankfully, in Canada, we’ve been able to create a system of national parks and protected areas in far less time than it takes to build a mountain range. With the 125th anniversary of Banff National Park celebrations scheduled for this November, Parks Canada will recognize more than a century of protecting natural wonders and cultural treasures across this country. We have come a long way from our humble beginnings in 1885 (Banff National Park was originally only 26 square kilometres in size). Today we can look back with pride at the many achievements and highlights realized over the years as we work to maintain our existing protected areas and create new ones. Here are five key achievements accomplished over the past 125 years worthy of remembering in this celebratory period: The National Parks Act (1930) hat makes a protected area a protected area, and to what lengths should we go to ensure that these special places retain their W special character and identity both now and for future generations? These are exactly the kinds of questions that are answered and upheld by law in Canada’s National Parks Act, which was the brainchild of J.B. Harkin, known by some as the father of Canada’s national parks. -

1 Ii Edycja „Ogólnopolskiego Konkursu Wiedzy O Kanadzie

II EDYCJA „OGÓLNOPOLSKIEGO KONKURSU WIEDZY O KANADZIE- DISCOVER CANADA 2015” ETAP SZKOLNY Czas pracy: 90 minut Liczba punktów możliwych do uzyskania: 110 WYNIK IMIĘ I NAZWISKO UCZNIA ………………………………………………………………………………………………… SZKOŁA …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. IMIĘ I NAZWISKO NAUCZYCIELA PROWADZĄCEGO …………………………………………………………… Arkusz liczy 7 stron i zawiera 110 pytań otwartych i zamkniętych. W pytaniach zamkniętych tylko jedna odpowiedź jest poprawna. W pytaniach otwartych wymagana jest pełna poprawność. Test został podzielony na dwie części leksykalno-gramatyczną i kulturową. Prosimy o zaznaczanie prawidłowych odpowiedzi na arkuszu. Test należy rozwiązywać samodzielnie. Good luck! CZĘŚĆ LEKSYKALNO-GRAMATYCZNA I. Choose the correct item. 1. Jenny will soon have this place looking spick and ……………….. a) quiet b) sound c) span d) well 2. Robert, like many children of his age, is prone to throwing a(n) ……………….. a) tantrum b) mood c) outburst d) temper 3. Lucy and Martha are as different as chalk and ……………….. It’s hard to believe that they are sisters. a) chair b) cheese c) chimney d) hair 4. It’s a ……………….. in the dark, but it might work. a) shot b) glow c) glimmer d) shouting 5. She had the ……………….. to speak to her father like that! a) leg b) cheek c) neck d) spine 6. I can’t sleep at night! I think I should ……………….. the amount of coffee and tea I drink. a) cut off b) cut off from c) cut down on d) cut out 7. Sally was dissatisfied with the quality of her new MP3 player and was given a full ……………….. from the shop. a) refund b) return c) replacement d) compensation 8. The hotel we stayed in was completely off the ………………. -

THE SEVEN WONDERS of CANADA Introduction

THE SEVEN WONDERS OF CANADA Introduction In the summer of 2007, the Canadian new. The original Seven Wonders of the Focus In this News in Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) World appeared on a list created around Review story, organized a contest to determine the 300 BCE. This “Ancient Wonders” we investigate Seven Wonders of Canada. Canadians list, as it is commonly called, was used the results of were encouraged to nominate any natural as a benchmark for all future wonders the recent CBC- or human-made wonder in the nation. lists. And it contains some of the most inspired contest Millions of Canadians participated. amazing feats of engineering in human to select the The final selections were made by a history. Seven Wonders of Canada. panel of respected judges. Only two Over the past 20 years, a number of of the final seven selections on the locations and sites have been designated judges’ list were from the top seven list as “Modern Wonders.” But the lists Definition nominated by Canadians. This caused differ depending on the criteria used to The notation quite an outpouring of sentiment. define “wonderfulness.” One of the lists CE stands for Many Canadians felt the final seven focuses on engineering wonders (those Common Era and wonders did not reflect the opinions of created by humans), while another refers reflects the time “average” Canadians who had taken to natural wonders. The most recent list, period that began with the birth the time to vote. The judges, however, released in July 2007, is the result of of Jesus Christ. -

Feasibility Study – Final Report

Kinghorn Rail‐to‐Trail Initiative Feasibility Study – Final Report March 31, 2011 by with Rod Bilz, David Andersen and for Project Contacts Shaun Karsten Kinghorn Trail Project Coordinator Phone: 807‐629‐4817 Email: [email protected] Sarah Lewis Economic Development Officer, Town of Nipigon Phone: 807‐887‐3135 (ext 26) Email: [email protected] Sarah Clowes Economic Development Officer, Town of Red Rock) Phone: 807‐886‐2704 Email: [email protected] John Cameron Tourism Development Officer, City of Thunder Bay Phone: 807‐625‐3231 Email: [email protected] Kirsten Spence Ontario Trails Coordinator, Trans Canada Trail s Phone: 705‐746‐1283 Email: [email protected] Dave Harris Reeve, Dorion Township Phone: 807‐857‐2289 Email: [email protected] Alana Bishop Councillor, Municipality of Shuniah Phone: (807) 977‐1436 Email: [email protected] Rick MacLeod Farley Principal Consultant, MacLeod Farley & Associates Phone: 519‐370‐2332 E‐mail: [email protected] Kinghorn Rail‐to‐Trail Feasibility Study – Final Report March 31, 2011 Contents 1. Executive Summary.......................................................................................................... 1 2. Trail Initiative Context ..................................................................................................... 5 2.1 The Proponents – Nipigon to Thunder Bay ..................................................................... 7 2.2 The Trans‐Canada Trail.................................................................................................. -

The Journal of Canadian Wilderness Canoeing

Spring 2008 The Journal of Canadian Wilderness Canoeing Outfit 132 Lands Reborn photo: George Douglas photo: NOTMAN’S DYKE - A solitary canoe, piercing into a vanishing wilderness untouched by time, heads up the Dease River in the late summer of 1911. GeorgeMEET Douglas Mr. DOUGLAS and August - ThisSandberg 1911 were photo making of George their firstDouglas forway was in sentthese to forlorn us by landsa subscriber. where they We certainlywould meet recognize traditional the Inuit pose and and search forlocation the riches as ofthe the Douglas Coppermine cabin across at the the mouth bounds of the of history. Dease RiverDouglas’ in rarethe northeast 1914 book, corner Lands Forlorn of Great is beingBear Lake,reprinted though with weall thewere photos not and anfamiliar updated withforward this to particular properly place photo this and book the in clothing its unique Douglas moment is ofwearing. history. DouglasThe self-portrait called this byspot the Notman’s author Dyke,of Lands perhaps Forlorn, alluding is one to, William Notman, the famed late 19th century photographer. See page 6. of many great photos from a book that is simply begging to be republished. But by whom? See Editor’s Notebook on Page 3 for www.ottertooth.com/che-mun Spring Packet This is a fabulous resource and I can only im- agine what Eric Morse and his group would think of such incredible technology. Of course the problem is printing them. Only a high scale plotter could print these maps a proper size but there is nothing stopping you from cropping out the sections you need and making smaller one. -

Annotations to Accompany the Many Sides of Robert Legget

ANNOTATIONS to accompany THE MANY SIDES OF ROBERT F. LEGGET Canadian Civil Engineer, Geologist and Historian by Doug VanDine August 2020 Robert F. Legget Page iii Table of Contents Page Ch Legget Memoir VanDine Additional Information Text Annotation Frontispiece and Dedication i - Table of Contents iii - Foreword v - 1 Introduction 1-1 1-4 2 The Legget Family 2-1 2-3 3 Early Years (1904-1922) 3-1 3-4 4 Special Note to the Reader and Apologia 4-1 4-4 5 Early Training (1922-1929) 5-1 5-4 6 University and London Years (1922-1929) 6-1 6-7 7 Canada Pre-ConferenceA (1929-1936) 7-1 7-7 8 First International Conference (1936) 8-1 8-4 9 Early Years in Canada (1929-1936) 9-1 9-9 10 Developments in [Eastern] Canada (1936-1939) 10-1 10-6 11 The War Years (1939-1945) 11-1 11-12 12 The Post-war Years (1945-1947) 12-1 12-8 13 University Years in Canada (1936-1947) 13-1 13-12 14 Ottawa (1947 and On) 14-1 14-8 The Associate Committee B 15-1 15-24 Track Studies 15-8 15-27 Snow Studies 15-10 15-30 Muskeg Studies 15-11 15-33 15 Permafrost Studies 15-12 15-33 Soil Mechanics Studies 15-13 15-34 Associate Committee: Operations 15-14 15-34 Associate Committees in General 15-22 15-38 Division of Building Research Years 16 16-1 16-15 (1947-1969) 17 L’Envoi 17-1 17-3 18 Appendices 18-1 18-13 Appendix A: Account of the First Conference from the 18-2 - Engineering Journal Appendix B: [The Associate Committee; an Outside View] 18-9 - Appendix C: A Note on Early Workers in Canada 18-11 - continued… A International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, held at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, June 22-26, 1936.