Challenges in the Cost Structure of Browser Tab Usage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineering Accessible Web Applications

Universidad Nacional de La Plata Facultad de Informática Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor (Ph.D.) in Informatics Science Engineering Accessible Web Applications. An Aspect-Oriented Approach Author: Mg. Adriana E. Martín Supervisor: Ph.D. Alejandra Cechich Co-Supervisor: Ph.D. Gustavo Rossi September 2011 ABSTRACT Building Accessible Web applications is nowadays a must. Every day more and more users with different abilities and/or temporally or permanent disabilities are accessing the Web, and many of them have special difficulties in reaching the desired information. However, the development of this kind of Web software is complicated for several reasons. Though some of them are technological, the majority are related with the need to compose different and, many times, unrelated design concerns which may be functional as in the case of most of the specific application’s requirements, or non- functional such as Accessibility itself. Even though, today there is a huge number of tools and proposals to help developers assess Accessibility of Web applications, looking from the designer perspective, there is no such a similar situation. It seems that creating accessible Web sites is more expensive and complicated than creating Web sites and then assessing/modifying them. Although this feeling may be largely true, the benefits of modelling Accessibility at early design stages outweigh the needs of a developer to implement that Accessibility. In this thesis, we present a novel approach to conceive, design and develop Accessible Web applications in an Aspect-Oriented manner. In order to reach our goal, we provide some modeling techniques that we specifically developed for handling the non- functional, generic and crosscutting characteristics of Accessibility as a quality factor concern. -

![[MS-HTML401]: Internet Explorer HTML 4.01 Standards Support](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4493/ms-html401-internet-explorer-html-4-01-standards-support-234493.webp)

[MS-HTML401]: Internet Explorer HTML 4.01 Standards Support

[MS-HTML401]: Internet Explorer HTML 4.01 Standards Support Document Intellectual Property Rights Notice for Open Specifications Documentation . Technical Documentation. Microsoft publishes Open Specifications documentation (“this documentation”) for protocols, file formats, data portability, computer languages, and standards support. Additionally, overview documents cover inter-protocol relationships and interactions. Copyrights. This documentation is covered by Microsoft copyrights. Regardless of any other terms that are contained in the terms of use for the Microsoft website that hosts this documentation, you can make copies of it in order to develop implementations of the technologies that are described in this documentation and can distribute portions of it in your implementations that use these technologies or in your documentation as necessary to properly document the implementation. You can also distribute in your implementation, with or without modification, any schemas, IDLs, or code samples that are included in the documentation. This permission also applies to any documents that are referenced in the Open Specifications documentation. No Trade Secrets. Microsoft does not claim any trade secret rights in this documentation. Patents. Microsoft has patents that might cover your implementations of the technologies described in the Open Specifications documentation. Neither this notice nor Microsoft's delivery of this documentation grants any licenses under those patents or any other Microsoft patents. However, a given Open Specifications document might be covered by the Microsoft Open Specifications Promise or the Microsoft Community Promise. If you would prefer a written license, or if the technologies described in this documentation are not covered by the Open Specifications Promise or Community Promise, as applicable, patent licenses are available by contacting [email protected]. -

The Technical Specification for Content Development Is for General Information Purposes Only

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION FOR CONTENT DEVELOPMENT VERSION: 6.0 DATE: 22 DECEMBER, 2009 Commercial in Confidence © Curriculum Corporation, 2009 Technical Specification for Content Development Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Purpose ........................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Obligations of The Le@rning Federation .................................................... 2 1.3 Monitoring and usage .................................................................................... 2 1.4 Conformance .................................................................................................. 2 1.5 Conventions used in this document ............................................................ 2 2 PRINCIPLES ................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Accessibility ................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Useability ........................................................................................................ 3 2.3 Interoperability ............................................................................................... 3 2.4 Flexibility ......................................................................................................... 3 2.5 Durability ........................................................................................................ -

Technical Specification Guide for Online Resources

Technical specification guide for online resources Version 7.3 March 2012 Technical specification guide for online resources Disclaimer The material contained in the Technical specification guide for online resources is for general information purposes only. Any use of the Technical specification guide for online resources is at your own risk. To the extent permitted by law, Education Services Australia will not be liable for any loss or damage suffered as a result of any party relying upon the Technical specification guide for online resources. © Education Services Australia 2012 Version 7.3 Page 2 of 28 Technical specification guide for online resources Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Obligations of Education Services Australia .................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Development, monitoring and usage ............................................................................................................ 5 1.4 Associated standards .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Conformance ............................................................................................................................................... -

Viewing Books in the Bible Collection 34 Comparing Versions of the Bible 35

WordCruncher User Guide For General Users Last updated August 24, 2020 Copyright © 1991–2020 Brigham Young University Provo, Utah, USA. All rights reserved. WordCruncher® Copyright © 1991–2020 Brigham Young University Provo, Utah, USA. All rights reserved. WordCruncher User Guide for General Users © First Edition March 2020 WordCruncher Version 7.1.100, Build 100 as of March 24, 2020 WordCruncher® and the WordCruncher logo are registered trademarks of Brigham Young University. WordCruncher is a closed source program. While WordCruncher Development tries to give the best resources to users, we reserve the right to make changes to any of the features, reports, and datasets within WordCruncher. Suggestions for improvements are welcome but will be evaluated based on current priorities. The use of WordCruncher is free. Books that are purchased through the bookstore are connected to a user account. The WordCruncher Support team keeps a record of all book purchases. If there is any loss of data, please contact [email protected] with your user information. Licensor makes no warranties, whether express or implied, including the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, and specifically no warranties or representations are made with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the data. 2 Table of Contents About WordCruncher 3 General Purposes of WordCruncher 4 Studying Texts Analyzing Linguistic Features 4 Getting Started 5 Downloading Books 5 Downloading a Free Book Available on WordCruncher 5 Downloading the -

Web Browsers Namely Mozilla Firefox, Internet Explorer, Google Chrome, Opera

12 ABSTRACT Web browser is the most commonly used client applicationWeb and speedBrowsers and efficiency of our online work depends on browser to a great extent. As the market is flooding with new browsers there is a lot of confusion in everyone’s mind as to which is the best browser.Our project aims to answer this question. We have done a comparative study of the four most popular web browsers namely Mozilla Firefox, Internet Explorer, Google Chrome, Opera. In the first phase of our project v arious comparison parameters are selected which can be broadly cat egorized into -General Features, Security features and browser extensibility features. Using the selected benchmarking tools each browser is tested. We have also use our own test scripts for some parameters .Depending on the performance of the browser points are assignedSubmitted to each browser by .Public opinion is considered for usability issue and finally we have come to a conclusion t hat opera and firefox are leading the browser war. firefox has finished first scoring 49.84 and opera has scored the next highest 48.90 Our other contributions include a K-chromium browserAmogh ,addon Kulkarni for firefox and (05CO05) scripts showing the major browser attacks. Jaison Salu John (05CO29) The report gives details of work done by our team from Jan 6 th 2008 till March 29 th 2008. Yohan John Thampi (05CO67) Shravan Udaykumar (05CO59) I. INTRODUCTION Gaurav Prasad(08IS03F) The World Wide Web has come a long way in itsVrinda short existence. Halarnkar Without it, (08IS04F) many people wouldn’t know what to do with their day. -

Development and Functioning of Expert Systems As Illustrated by Selected Examples

Anna Golik, Eng., Maciej Golik, Eng., Rafał Dreżewski, PhD, Eng. The School of banking and Management [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTIONING OF EXPERT SYSTEMS AS ILLUSTRATED BY SELECTED EXAMPLES Introduction In many areas of human activity a person with theoretical knowledge and practical experience (i.e. an expert) is usually an indispensable element of a decision making process. However, it often happens that an expert in a given field is not available or difficult to contact. The idea of expert systems appeared as a solution to such problems. In some cases, an expert system is able to replace a human expert in a given field or to function as a system supporting his/her decision making processes by providing alternative solutions to problems under investigation. The practical aim of developing expert systems is to support key human decisions (to provide expert opinion) by drawing conclusions from the expert’s knowledge that is introduced to the system. In some cases it is even aimed to replace the human thinking process by a machine’s reasoning algorithm1. Currently, an immense amount of data is collected that comes from various sources (statistics, medical files, seismographs, Large Hadron Collider, etc.). In order to draw conclusions from data, the assistance of the computing power of computers is required and expert systems can be applied, which provide the opportunity of reliable reasoning from historical data 2 (i.e. from the data collected before). The term expert systems may also include self-learning expert systems, i.e. -

Techniques for User Agent Accessibility Guidelines

Techniques for User Agent Accessibility Guidelines W3C WD-WAI-USERAGENT-TECH-19980309 Techniques for User Agent Accessibility Guidelines W3C Working Draft 9-Mar-1999 This version: http://www.w3.org/WAI/UA/WD-WAI-USERAGENT-19990309/wai-useragent-tech Latest version: http://www.w3.org/WAI/UA/WD-WAI-USERAGENT/wai-useragent-tech Latest public version: http://www.w3.org/TR/WD-WAI-USERAGENT/wai-useragent-tech Previous version: http://www.w3.org/WAI/UA/WD-WAI-USERAGENT-19990210/wai-useragent-tech Latest "User Agent Accessibility Guidelines": http://www.w3.org/WAI/UA/WD-WAI-USERAGENT Latest public version of "User Agent Accessibility Guidelines": http://www.w3.org/TR/WD-WAI-USERAGENT Editors: Jon Gunderson <[email protected]> Ian Jacobs <[email protected]> Copyright W3C (MIT, INRIA, Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C liability, trademark, document use and software licensing rules apply. Abstract This document describes techniques that user agent developers may use to satisfy the checkpoints listed in "User Agent Accessibility Guidelines." Techniques relate to the accessibility of user interfaces, content rendering, program interfaces, and accessibility features of languages such as HTML, CSS and SMIL. Like "User Agent Accessibility Guidelines", the current document emphasizes the accessibility of interoperability between two important classes of user agents - graphical desktop browsers and dependent assistive technologies (including screen readers, screen magnifiers, and voice input software). However, it is meant to be applicable to user agents in general, including text and voice browsers, and multimedia players. While "User Agent Accessibility Guidelines" has been designed to be a stable document of principles, the current document will continue to evolve as technologies change and user agent manufacturers discover more effective techniques for designing accessible user agents. -

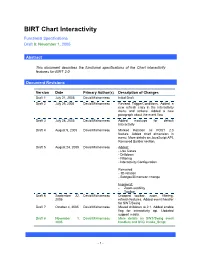

BIRT Chart Interactivity Functional Specifications Draft 8: November 1 , 2005

BIRT Chart Interactivity Functional Specifications Draft 8: November 1 , 2005 Abstract This document describes the functional specifications of the Chart interactivity features for BIRT 2.0 Document Revisions Version Date Primary Author(s) Description of Changes Draft 1 July 21, 2005 David Michonneau Initial Draft Draft 2 July 26, 2005 David Michonneau Revised TriggerConditions. Added a new refresh entry in the interactivity menu and actions. Added a new paragraph about the event flow Draft 3 July 28, 2005 David Michonneau Added mockups for default interactivity Draft 4 August 5, 2005 David Michonneau Marked Rotation as POST 2.0 feature. Added chart dimension in menu. More details on JavaScript API. Removed Builder section. Draft 5 August 24, 2005 David Michonneau Added: - Use Cases - Drilldown - Filtering - Interactivity Configuration Removed: - 3D rotation - Subtype/Dimension change Improved: - Zoom usability - Toolbar Draft 6 September 22, David Michonneau Dropped toolbar, zoom, filtering, 2005 refresh features. Added event handler for SWT/Swing Draft 7 October 4, 2005 David Michonneau Moved drilldown to 2.1. Added enable flag for interactivity api. Updated support matrix. Draft 8 November 1, David Michonneau More details on SWT/Swing event 2005 handlers and SVG Invoke_Script - 1 - Functional Specification (Chart Interactivity) Contents 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................................................3 2. Use Cases.................................................................................................................................................3 -

Javascript (Part 1)

Session 6 – JavaScript (Part 1) Session 6 JavaScript Part 1 Reading ] Reading \ Wikipedia en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Javascript \ Web Developers Notes www.webdevelopersnotes.com/tutorials/javascript/ \ JavaScript Debugging www.w3schools.com/js/js_debugging.asp ] jQuery-DOM http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/xml/tutorials/x- processxmljquerytut/index.html We cover jQuery later in the course 2 Robert Kelly, 2018 9/18/2018 Robert Kelly, 2001-2018 1 Session 6 – JavaScript (Part 1) References ] Reference \ ECMAScript www.ecma-international.org/publications/files/ECMA-ST/Ecma-262.pdf \ Mozilla Guide https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference \ W3C www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40/interact/scripts.html 3 Robert Kelly, 2018 Reference Book ] JavaScript: The Definitive Guide by David Flanagan, O’Reilly Press, 6th Edition (might be available through Safari Books On-Line and Google Books) the only complete JavaScript book I have seen that is written from a CS perspective 4 Robert Kelly, 2018 9/18/2018 Robert Kelly, 2001-2018 2 Session 6 – JavaScript (Part 1) Background Reading ] Also possibly available through CS Library using Safari Books On-line \ Head First HTML5 Programming: Building Web Apps with JavaScript by Eric Freeman and Elisabeth Robson, O’Reilly Press \ XML In a Nutshell, Chapter 19 (DOM) Not written for CS majors, but reasonably correct 5 Robert Kelly, 2018 Learning Goals ] Understand differences of JavaScript as compared with Java ] Understand syntactic and semantic structure of JavaScript ] Understand use of events 6 -

Creating Online Content for Pocket PC Pocket Internet Explorer HTML

Creating Online Content for Pocket PC Seite 1 von 120 Pocket PC Development Guide Creating Online Content for Pocket PC What did you think of this topic? Send us feedback Built on Wednesday, May 07, 2003 Pocket PC Development Guide Pocket Internet Explorer HTML Element Reference This reference specifies the HTML elements that are supported for Microsoft® Windows® Powered Pocket PC with their attributes, values, and descriptions. What did you think of this topic? Send us feedback Built on Wednesday, May 07, 2003 Pocket PC Development Guide A Designates the start or destination of a hypertext link. The A element is an inline element and requires a closing tag. Attributes Attribute Value Description ACCESSKEY 0…9, #, * A method of giving access or focus to an active HTML element by using a keypad number. Not supported for Pocket PC 2000 or Pocket PC 2002. CLASS Associates the element with a cascading style sheets style. Not supported for Pocket PC 2000 or Pocket PC 2002. HREF URL A string that specifies a destination URL or anchor point. For example, #bookmark, mailto: or tel: Not supported for Pocket PC 2000 or Pocket PC 2002. ID Uniquely identifies the element within a document. Not supported for Pocket PC 2000 or Pocket PC 2002. NAME String Specifies a name or bookmark for the current section of the document. ONCLICK An event that occurs when the user chooses the A element. file://C:\Temp\~hh1E96.htm 08.04.2005 Creating Online Content for Pocket PC Seite 2 von 120 Not supported for Pocket PC 2000. STYLE Provides the definition of the cascading style sheets styles used for this element. -

Extending the Web3d: Design of Conventional GUI Libraries in X3D Ivan Sopin Felix G

Extending the Web3D: Design of Conventional GUI Libraries in X3D Ivan Sopin Felix G. Hamza-Lup Computer Science Computer Science Armstrong Atlantic State University Armstrong Atlantic State University 11935 Abercorn Street 11935 Abercorn Street Savannah, GA 31419 Savannah, GA 31419 +1 (912) 401-1407 +1 (912) 344-2680 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT graphics standard with wide recognition among professional Extensible 3D (X3D) modeling language is one of the leading organizations, researchers, 3D designers, and Web3D enthusiasts Web3D technologies. Despite the rich functionality, the language around the globe. Yet one important feature that the language still does not currently provide tools for rapid development of lacks is a toolset for creating conventional user interfaces (UIs). conventional graphical user interfaces (GUIs). Every X3D author Typically, to provide a UI for each new application, the X3D is responsible for building—from primitives—a purpose-specific author has to design an entirely different set of interface set of required interface components, often for a single use. components. Most of these implementations are very limited in functionality and only serve their ad-hoc purpose. We address the challenge of creating consistent, efficient, interactive, and visually appealing GUIs by proposing the X3D We address the challenge of creating consistent, efficient, easily User Interface (X3DUI) library. This library includes a wide range controllable, and visually appealing interfaces by proposing the of cross-compatible X3D widgets, equipped with configurable Extensible 3D User Interface (X3DUI) library. This library is a appearance and behavior. With this library, we attempt to wide range of cross-compatible X3D widgets with configurable standardize the GUI construction across various X3D-driven appearance and behavior.