La Traviata’ Makes for a Chilly Evening in LA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sold-Out Sessions to Tan Dun's the First Emperor Even Before Opera

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE More Shows for The Metropolitan Opera in HD Digital at Golden Village VivoCity Sold-out Sessions to Tan Dun’s The First Emperor even before Opera premieres tomorrow Singapore, 19 September 2007 – Due to popular and overwhelming demand, Golden Village has added 7 more shows for The Metropolitan Opera: Tan Dun’s The First Emperor in High-Definition (HD) Digital exclusively at GV VivoCity from 20 September to 3 October 2007 daily. 5 out of the original 9 sessions for The First Emperor have been fully sold out before the opera premieres tomorrow. Remaining sessions are left with tickets on the first two rows from the screen. Golden Village is now adding new sessions in response to the great demand. Opera fans who were not able to catch The Metropolitan Opera in HD Digital at GV VivoCity will now be given another chance to experience the phenomenon. Screening details: 20 – 26 September 2007 – 7pm daily and 3.30pm on the weekends 4 sessions remaining and tickets are selling fast! Golden Village Seats only available in the first two rows from the screen . VivoCity 27 September – 3 October 2007 – 7pm daily 7 new sessions added Tickets to The First Emperor are at $15 per ticket. Tickets are available at GV Box Offices and at www.gv.com.sg . Staged by world-renown film director Zhang Yimou, written by acclaimed Academy Award winner Tan Dun, The First Emperor stars Plácido Domingo (one of the Three Tenors ) as Qin Shi Huang. Please visit www.gv.com.sg for more information. -

Plácido Domingo – a Short Biography

Plácido Domingo – a short biography Plácido Domingo was born in the Barrio de Salamanca district of Madrid on January 21, 1941. He is the son of Plácido Domingo Ferrer and Pepita Embil Echaníz, two Spanish Zarzuela performers, who nurtured his early musical abilities. Domingo's father, a violinist performing for opera and zarzuela orchestra, was half Catalan and half Aragonese, while his mother, an established singer, was a Basque. After moving to Mexico at the age of 8, Plácido Domingo went to Mexico City’s Conservatory of Music to study piano and conducting, but eventually was sidetracked into vocal training after his voice was discovered. The highly gifted singer had his first professional engagement as accompanist to his mother in a concert at Mérida, Yucatan, in 1957. He soon achieved great acclaim at international level. Challenged by cosmopolitan groups and new roles In 1961, Domingo made his operatic debut in a leading role as Alfredo in La Traviata at Monterrey. The performance of La Traviata included a baritone singing in Hungarian, a soprano in German, a tenor in Italian, and the chorus in Hebrew. Domingo credits this cosmopolitan group for improving his abilities in several languages. At the end of 1962, he signed a six month contract with the Israel National Opera in Tel Aviv but later extended the contract and stayed for two and a half years, singing in 280 performances and incorporating 12 different roles. Domingo has sung and continues to sing in every important Opera House in the world including the Metropolitan Opera in New York, Milan’s La Scala, the Vienna State Opera, London's Covent Garden, Paris' Bastille Opera, the San Francisco Opera, Chicago's Lyric Opera, the Washington National Opera, the Los Angeles Opera, the Teatro del Liceu in Barcelona, Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires, the Real in Madrid, and at the Bayreuth and Salzburg Festivals. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

A Season of Thrilling Intrigue and Grand Spectacle –

A Season of Thrilling Intrigue and Grand Spectacle – Angel Blue as MimÌ in La bohème Fidelio Rigoletto Love fuels a revolution in Beethoven’s The revenger becomes the revenged in Verdi’s monumental masterpiece. captivating drama. Greetings and welcome to our 2020–2021 season, which we are so excited to present. We always begin our planning process with our dreams, which you might say is a uniquely American Nixon in China Così fan tutte way of thinking. This season, our dreams have come true in Step behind “the week that changed the world” in Fidelity is frivolous—or is it?—in Mozart’s what we’re able to offer: John Adams’s opera ripped from the headlines. rom-com. Fidelio, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. Nixon in China by John Adams—the first time WNO is producing an opera by one of America’s foremost composers. A return to Russian music with Musorgsky’s epic, sweeping, spectacular Boris Godunov. Mozart’s gorgeous, complex, and Boris Godunov La bohème spiky view of love with Così fan tutte. Verdi’s masterpiece of The tapestry of Russia's history unfurls in Puccini’s tribute to young love soars with joy a family drama and revenge gone wrong in Rigoletto. And an Musorgsky’s tale of a tsar plagued by guilt. and heartbreak. audience favorite in our lavish production of La bohème, with two tremendous casts. Alongside all of this will continue our American Opera Initiative 20-minute operas in its 9th year. Our lineup of artists includes major stars, some of whom SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS we’re thrilled to bring to Washington for the first time, as well as emerging talents. -

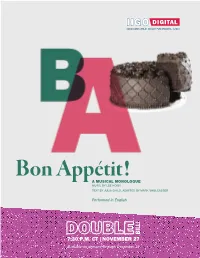

Bon Appétit!A MUSICAL MONOLOGUE MUSIC by LEE HOIBY TEXT by JULIA CHILD, ADAPTED by MARK SHULGASSER

Bon Appétit!A MUSICAL MONOLOGUE MUSIC BY LEE HOIBY TEXT BY JULIA CHILD, ADAPTED BY MARK SHULGASSER Performed in English 7:30 P.M. CT |NOVEMBER 27 Available on demand through December 26 Bon Appétit! Background Cast Lee Hoiby’s one-woman, one-act opera Bon Julia Child Jamie Barton ‡ Appétit! premiered in 1989 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, with Jean Stapleton performing the role ‡ Former Houston Grand Opera Studio artist of Julia Child. It was presented as a curtain raiser for Hoiby’s The Italian Lesson, also a musical monodrama. Creative Team The Story Pianist Jonathan Easter* Co-Directors Ryan McKinny ‡ Bon Appétit is a conflation of two episodes of Julia and Tonya McKinny * Child’s cooking show, The French Chef, in which she narrates—with all her wit, antics, and charisma—the * Houston Grand Opera debut baking of the perfect chocolate cake, Le gâteau au ‡ Former Houston Grand Opera Studio artist chocolat l’éminence brune. The entire staff of HGO contributed to the success of this production. For a full listing of the company’s staff, Fun Fact please visit HGO.org/about-us/people. Houston favorite, HGO Studio alumna, and beloved Performing artists, stage directors, and choreog- mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton portrays Child in a role raphers are represented by the American Guild of she has made her own, performing in venues including Musical Artists, the union for opera professionals in New York’s Carnegie Hall. the United States. Underwriters Video and Audio Production Streaming Partner Produced in association Jennifer and Benjamin Fink Keep the Music Going Productions with Austin Opera Bon Appétit! RYAN MCKINNY Richard Tucker Award, both Main and Song Prizes at the BBC Cardiff (United States) Singer of the World Competition, Metropolitan Opera National Council CO-DIRECTOR Auditions, and a Grammy nominee. -

Soprano Eglise Gutiérrez Returns to Florida Grand Opera in Donizetti's

Media Contact: Justin Moss, [email protected] , 305-854-1643 ext. 1600 Soprano Eglise Gutiérrez returns to Florida Grand Opera in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor Miami, FL – January 4, 2010. Florida Grand Opera’s 2009-10 season continues in January with the return of soprano Eglise Gutiérrez in the title role of a new production of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. This bell-canto masterpiece is based on Sir Walter Scott’s historical novel, The Bride of Lammermoor, and tells the story of a wedding where celebration turns to horror as the young bride enters in her bloodstained nightgown clutching the knife with which she has killed her new husband. The ensuing mad scene is arguably the most famous in all of opera, and has served as a showcase for the world’s leading coloratura sopranos. This new Florida Grand Opera production is designed by André Barbe, and directed by Renaud Doucet. Eglise Gutiérrez’s highly acclaimed performances of Violetta in FGO’s 2008 production of La traviata were a highlight of the season, and she is becoming internationally recognized as one of the leading bel canto sopranos. The months prior to her FGO appearance as Lucia will find her in productions at Opéra de Montréal, the Savonlinna Festival, the Ravinia Festival, the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Seattle Opera, and the Dresden Opera. The up and coming Mexican soprano María Alejandres will perform the title role of Lucia di Lammermoor on January 27 and 30, prior to her performances of Juliette in Roméo et Juliette at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden. -

Enrique Ferrer

Enrique Ferrer Nace en Madrid. Comienza sus estudios en el Real Conservatorio Superior de Música de Madrid, donde estudia bajo la dirección de la Mª Luisa Castellanos en la Cátedra de Pedro Lavirgen. En 1989 es contratado por José Tamayo en su compañía La Antología de la Zarzuela para una tourne mundial. En 1993 fue premiado en el Concurso Nacional de Canto “Ciudad de Logroño”. Un año más tarde gana una beca de estudios en la academia The Academy of Vocal Arts de Filadelfia, Estados Unidos, donde estudia con los maestros Cristopher Macatsoris y Bill Shuman. Protagoniza las óperas, “Falstaff “,“Don Giovanni”, “Così fan tutte” y “Don Pasquale”, El Mesías y varios conciertos en el Carnegie Hall de New York. Obtiene grandes sucesos de público y de crítica que lo califica como “unas de las grandes promesas jóvenes de la lirica”. Es finalista en el Concurso Internacional de Canto en Philadelphia “Luciano Pavarotti”. El Maestro se muestra entusiasmado por las dotes vocales y artística del joven tenor. Premiado en el Concurso Internacional de Canto Jaime Aragall en Barcelona. Durante 1995 formó parte de una producción de “Luisa Fernanda” en el Teatro Colón de Bogotá. En 1997 debuta en el Teatro Lírico Nacional de la Zarzuela “El Rey que Rabió” de R. Chapí, “La Fama del Tartanero” del mismo Teatro, “La Canción del Olvido”, “Don Gil de Alcalá” en producción del Teatro de la Zarzuela. Ha participado en varias grabaciones para televisión de zarzuelas como “Los Gavilanes” y “La del Manojo de Rosas”. Desde el 2004 participa en todas las galas de zarzuela de año nuevo que se realizan en el Auditorio Nacional de Música de Madrid. -

Don Pasquale

Gaetano Donizetti Don Pasquale CONDUCTOR Dramma buffo in three acts James Levine Libretto by Giovanni Ruffini and the composer PRODUCTION Otto Schenk Saturday, November 13, 2010, 1:00–3:45 pm SET & COSTUME DESIGNER Rolf Langenfass LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler This production of Don Pasquale was made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund. The revival of this production was made possible by a gift from The Dr. M. Lee Pearce Foundation. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 129th Metropolitan Opera performance of Gaetano Donizetti’s Don Pasquale Conductor James Levine in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Don Pasquale, an elderly bachelor John Del Carlo Dr. Malatesta, his physician Mariusz Kwiecien* Ernesto, Pasquale’s nephew Matthew Polenzani Norina, a youthful widow, beloved of Ernesto Anna Netrebko A Notary, Malatesta’s cousin Carlino Bernard Fitch Saturday, November 13, 2010, 1:00–3:45 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, the Neubauer Family Foundation. Bloomberg is the global corporate sponsor of The Met: Live in HD. Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera Mariusz Kwiecien as Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Dr. Malatesta and Musical Preparation Denise Massé, Joseph Colaneri, Anna Netrebko as Carrie-Ann Matheson, Carol Isaac, and Hemdi Kfir Norina in a scene Assistant Stage Directors J. Knighten Smit and from Donizetti’s Don Pasquale Kathleen Smith Belcher Prompter Carrie-Ann Matheson Met Titles Sonya Friedman Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs by Metropolitan Opera Wig Department Assistant to the costume designer Philip Heckman This performance is made possible in part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. -

La Traviata Dido and Aeneas / Bluebeard's Castle Sondra

La Traviata GIUSEPPE VERDI September 13 – 28, 2014 Production made possible by generous gifts from The Milan Panic Family and Barbara Augusta Teichert. Special underwriting support from Joyce and Aubrey Chernick. HENRY PURCELL / Dido and Aeneas / Bluebeard’s Castle BÉLA BARTÓK October 25 – November 15, 2014 Production made possible by the generous support of the Tarasenka Pankiv Fund (Tara Colburn). Support for the guest conductor provided by the Beatrix F. Padway and Nathaniel W. Finston Conductors Fund. Sondra Radvanovsky in Recital November 8, 2014 DANIEL CATÁN / Florencia en el Amazonas MARCELA FUENTES-BERAIN November 22 – December 20, 2014 Underwriting support from the Jane and Peter Hemmings Production Fund, a gift from the Flora L. Thornton Trust. Original production supported by Edward E. and Alicia Garcia Clark, an Anonymous Donor, AT&T, and Drs. Dennis and Susan Carlyle. THE FIGARO TRILOGY JOHN CORIGLIANO / The Ghosts of Versailles WILLIAM M. HOFFMAN February 7 – March 1, 2015 Production made possible in part by a generous gift from the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation. T H E F I G A R O T R I L O G Y The Barber of Seville GIOACHINO ROSSINI February 28 – March 22, 2015 Production made possible by generous funding from The Seaver Endowment and from The Alfred and Claude Mann Fund, in honor of Plácido Domingo. Noah’s Flood BENJAMIN BRITTEN March 6 – 7, 2015, at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels Production made possible with generous underwriting support from the Dan Murphy Foundation. T H E F I G A R O T R I L O G Y The Marriage of Figaro WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART March 21 – April 12, 2015 Production made possible by a generous gift from The Carol and Warner Henry Production Fund for Mozart Operas. -

Angela Maria Blasi Email: [email protected]

Angela Maria Blasi Email: [email protected] Biography Hailed by the New York Times for her 'deeply moving' interpretation of Cio Cio San in Madama Butterfly at the Los Angeles Opera, Angela Maria Blasi is regarded as one of the most important and most celebrated lyric sopranos of our time. She has performed regularly with the most prestigious international opera companies and festivals of the world including the Bavarian State Opera, Vienna Staatsoper, Salzburger Festspiele, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, La Scala Milan, Brussels La Monnaie, Maggio Musicale Firenze, Hamburgische Staatsoper, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Teatro Colon, Los Angeles Opera, Washington National Opera, New York City Opera, Palm Beach Opera, Opera Orchestra of New York and the Metropolitan Opera. Impeccable musicianship and phrasing, a seamless vocal technique, and an engaging stage presence are just some of the trademarks of her highly-acclaimed performances. A long-time member of the Bavarian State Opera, Angela carries the title of Bavarian Kammersaengerin and is the winner of numerous awards for her performances in Europe. She relocated from Germany to the U.S. in 2006 to teach privately and joined Columbia Artists Management in 2008, as an assistant to Matthew Epstein, former CAMI Artist Manager and Head of CAMI Vocal, LLC. She quickly advanced to Vice President and Artist Manager of the Epstein artist roster and other rising stars while maintaining a private vocal studio in the greater New York area. Fluent in three foreign languages, knowledgeable in the operatic and concert repertoire, Angela brings a unique and valuable perspective to her students with her passion for singing, first-hand knowledge of the physical, vocal, and emotional demands of an operatic career, her knowledge of opera as a 'business', as well as a keen understanding of the artistic temperament. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Summer Quarter 2017 (July - September) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more.