Are Small Mountainous Tropical Watersheds of Oceanic Islands Important for Carbon Export? E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

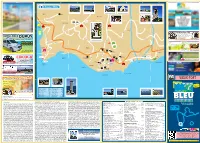

Guadeloupedos 2018 - 2019 Www Guadeloupe Best Of

2018 2019 2018 - 2019 English edition best of guadeloupe Dos best of guadeloupe www.petitfute.uk PUBLISHING Collection Directors and authors: Dominique AUZIAS and Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE Welcome to Authors: Nelly DEFLISQUESTE, SIMAX CONSULTANT-Christine MOREL, Patricia BUSSY, Johann CHABERT, Juliana HACK, Guadeloupe! Faubert BOLIVAR, Yaissa ARNAUD BOLIVAR, Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS and alter Publishing director: Stephan SZEREMETA Of all the "Lesser Antilles", the Guadeloupean Publishing team (France): Elisabeth COL, archipelago is the most surprising when it comes Silvia FOLIGNO, Tony DE SOUSA, Agnès VIZY to the variety of landscapes. A seaside destination Publishing team (World): Caroline MICHELOT, par excellence, Grande-Terre, with its crystal-clear Morgane VESLIN, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET, Jimmy POSTOLLEC, Elvane SAHIN water beaches and blue lagoons, delights lovers of sunbathing. In the coral funds, diving spots are STUDIO multiple, and even beginners, with mask and snorkel, Studio Manager: Sophie LECHERTIER assisted by Romain AUDREN can enjoy the underwater spectacle. But Mother Layout: Julie BORDES, Sandrine MECKING, Nature reserves many other surprises. Large and Delphine PAGANO and Laurie PILLOIS small wild coves for adventurers, lush tropical forest, Pictures and mapping management: vertiginous waterfalls, rivers with refreshing waters, Anne DIOT and Jordan EL OUARDI volcanic land, high limestone plateaus, steep cliffs, WEB fragile and mysterious mangrove… A biodiversity Web Director: Louis GENEAU de LAMARLIERE promising -

Les Communes Du Sud De La Guadeloupe Proprement Dite Gérard Lafleur

Document generated on 09/25/2021 6:35 p.m. Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe Les communes du sud de la Guadeloupe proprement dite Gérard Lafleur Number 150-151, May–August–September–December 2008 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1041708ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1041708ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe ISSN 0583-8266 (print) 2276-1993 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Lafleur, G. (2008). Les communes du sud de la Guadeloupe proprement dite. Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe, (150-151), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.7202/1041708ar Tous droits réservés © Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Les communes du sud de la Guadeloupe proprement dite Gérard Lafleur La création de trois communes distinctes – Basse-Terre, EXtra Muros (devenu Saint-Claude) et Dos-d’Âne (devenu GourbeYre) – par le décret colonial du 20 septembre 1837, est l’aboutissement d’une évolution de la mise en valeur du territoire qui commence dès les débuts de la coloni - sation. Nous traiterons donc des différentes étapes de cette évolution avec l’installation des premiers colons à VieuX-Fort et surtout à Rivière Sence, pour progressivement prendre possession du bord de mer puis très rapi - dement de la campagne environnante. -

Etat Des Lieux Rapport De Phase 2

DIRECTION DEPARTEMENTALE DE L ’E QUIPEMENT DE LA GUADELOUPE SERAU GESTION ET DEVELOPPEMENT EQUILIBRE DU LITTORAL GUADELOUPEEN Etat des lieux Rapport de phase 2 Septembre 2008 -RapportPH2.doc -RapportPH2.doc PG Direction Départementale de l’Equipement de la Guadeloupe - SERAU Page 1 GESTION ET DEVELOPPEMENT EQUILIBRE DU LITTORAL GUADELOUPEEN - PHASE 2 : ETAT DES LIEUX 1. LE MILIEU PHYSIQUE.................................................................... 9 1.1 L’occupation des sols de la bande littorale 9 1.2 Eléments physiques 15 1.2.1 Nature de la côte 15 1.2.2 Trait de côte et point d’érosion 21 1.2.3 Barrière et formations coralliennes 24 1.2.4 Eléments de bathymétrie 25 1.2.5 Courantologie 28 1.2.6 Points clés de l’état des lieux sur les éléments physiques 31 1.3 Le paysage 33 1.3.1 Les paysages emblématiques 33 1.3.1.1 Les côtes de la Basse-Terre 33 1.3.1.2 Les côtes de la Grande-Terre 39 1.3.1.3 Les côtes des « dépendances » : Marie-Galante, la Désirade dont Petite Terre et les Saintes 48 1.3.2 Projet de grand site 54 1.3.3 Paysages artificialisé ou minéral 55 1.3.4 Impact des aménagements liés aux énergies renouvelables sur le paysage 56 1.3.5 Impacts des carrières sur le paysage 58 1.3.6 Synthèse des points clés de l’état des lieux sur les paysages 59 2. LE PATRIMOINE NATUREL ........................................................... 60 2.1 Les principaux écosystèmes 60 2.1.1 Milieu terrestre 60 2.1.2 Milieu aquatique 62 2.1.3 Milieu marin 63 2.2 Biodiversité 67 2.2.1 Milieu terrestre 67 2.2.2 Milieu marin 67 2.3 Inventaires -

A Question That Counts in French West Indies Maritime Archaeology: Linking Historical and Archaeological Sources Jean-Sébastien Guibert

A Question That Counts in French West Indies Maritime Archaeology: Linking Historical and Archaeological Sources Jean-Sébastien Guibert To cite this version: Jean-Sébastien Guibert. A Question That Counts in French West Indies Maritime Archaeology: Linking Historical and Archaeological Sources. ACUA. Underwater Archaeology Proceedings, ACUA, 2014. hal-01443278 HAL Id: hal-01443278 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01443278 Submitted on 23 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A Question That Counts in French West Indies Maritime Archaeology: Linking Historical and Archaeological Sources Tis paper presents part of the results of historical research for a PhD thesis focusing on seafaring and maritime activity in Guadeloupe, French West Indies (FWI). Additionally, it discusses the possible identifcation of fve shipwreck sites that appear to date to the 19th century: Anse à la Barque, Pointe-à-Pitre, Baie des Saintes, Sainte-Anne and Le Moule shipwrecks. Introduction consulted. Archival research focused on records from the 17th century through to the end of the mid-19th Tis paper provides an overview of part of the results century, and research is still ongoing for records dating of a PhD thesis in history (Guibert 2013) focusing on through the end of 19th century. -

3-Histoire Des Antilles-Guyane Guadeloupe 1 BIB Art

Archives départementales de la Guadeloupe ème é 2 semestre 2016 é Réalisé par Anita Bouka, assistant de conservation principal Avec l’aide de Lydie Tania Biabiany Avant – propos Le catalogue des dernières acquisitions recense les documents entrés dans la bibliothèque des Archives départementales de Guadeloupe par achat, don ou dépôt légal. Les documents sont classés par thématique dans le cadre de classement développé à la page suivante. Dans le catalogue, les documents sont identifiés par une cote alphanumérique placée juste avant la notice. Pour consulter les documents, veuillez effectuer une demande de communication en salle de recherche en prenant soin de relever la cote du document qui vous intéresse. En effet, ces ouvrages ne sont pas encore tous accessibles via le système informatique dédié à cela en salle de recherche. 1 - S o m m a i r e - CADRE DE CLASSEMENT 1 – SCIENCES ET TECHNIQUES PROFESSIONNELLES……………………………………… 4 5 Archives, musées, bibliothèques : généralités …………………………………. 2 – HISTOIRE ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 10 11 Esclavage …………………………………………………………………………………………………...….. 15 Mémoire et réparation ………………………………………………………………………..…..…. 16 Colonie ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 17 Guerres ……………………………………………………………………………………………………..……. 18 Histoire générale …………………………………………………………………………………..……. 19 3 – HISTOIRE DES ANTILLES-GUYANE ………………………………………………………..……. ……………………………………………………………………………………………..……. 19 Guadeloupe ………………………………………………………………………………………………..……. 21 Martinique ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Petit Historique Des Grands Recensements Antillo-Guyanais Et En Particulier De La Guadeloupe Guy Stéhlé

Document generated on 10/02/2021 7:51 a.m. Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe Petit historique des grands recensements antillo-guyanais et en particulier de la Guadeloupe Guy Stéhlé Number 115, 1er trimestre 1998 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1043233ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1043233ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe ISSN 0583-8266 (print) 2276-1993 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Stéhlé, G. (1998). Petit historique des grands recensements antillo-guyanais et en particulier de la Guadeloupe. Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe, (115), 3–59. https://doi.org/10.7202/1043233ar Tous droits réservés © Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe, 1999 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Petit historique des grands recensements antillo-guyanais et en particulier de la Guadeloupe par Guy STÉHLÉ L'importance stratégique, militaire et économique des « Isles Fran çaises d'Amérique » conduisit très tôt le pouvoir central à demander aux gouverneurs locaux et au gouverneur général de lui fournir des informa tions détaillées sur l'état de ces colonies. C est Colbert, à son arrivée aux Affaires, qui donne l'impulsion déter minante. -

FEUILLE D'astreinte DU DEPARTEMENT : GUADELOUPE Vendredi 22 Décembre 2017

FEUILLE D'ASTREINTE DU DEPARTEMENT : GUADELOUPE Vendredi 22 Décembre 2017 Date Nom Pharmacie N°secteur villes - secteur Type Heures DES CITES UNIES-GIPHARMA QUARTIER HOTEL DE VILLE 20:00 à 08:00 n°971001 - Centre Grande-Terre 22/12/2017 97110 - POINTE-A-PITRE LE GOSIER - LES ABYMES - POINTE-A-PITRE Nuit Tel Garde Tel 0590837490 0590837490 Fax 0590916066 BERTHELOT-PERIN 65 BOULEVARD ROUGE ANSE BERTRAND - LE MOULE - MORNE A L EAU - 20:00 à 08:00 n°971002 - Nord et Est 22/12/2017 97160 - LE MOULE PETIT CANAL - PORT LOUIS - SAINT FRANCOIS - Nuit Tel Garde Grande-Terre Tel 0590235129 SAINTE ANNE 0690206608 Fax 0590235857 DE LA PLACE 10 RUE VOLCY BASTARD BAIE MAHAULT - BOUILLANTE - DESHAIES - GOYAVE - 20:00 à 08:00 22/12/2017 97170 - PETIT BOURG n°971003 - Nord Basse-Terre LAMENTIN - PETIT BOURG - POINTE NOIRE - Nuit Tel Garde Tel 0590948957 POINTE-A-PITRE - SAINTE ROSE 0690429789 Fax 0590948958 DE MARCO RUE PRINCIPALE BAILLIF - BASSE TERRE - BOUILLANTE - CAPESTERRE 20:00 à 08:00 22/12/2017 97125 - BOUILLANTE n°971004 - Sud Basse-Terre BELLE EAU - GOURBEYRE - SAINT CLAUDE - TROIS Nuit Tel Garde Tel 0590987141 RIVIERES - VIEUX HABITANTS 0590987141 Fax 0590988489 SUN PHARMACIE 2 RUE DE LA REPUBLIQUE 19:00 à 09:00 22/12/2017 97150 - SAINT MARTIN n°971005 - Saint Martin SAINT MARTIN Nuit Tel Garde Tel 0590875168 0590875168 Fax 0590877892 DE SAINT LOUIS RUE RAPHAEL JERPAN 19:00 à 07:30 CAPESTERRE DE MARIE GALANTE - GRAND BOURG - 22/12/2017 97134 - SAINT LOUIS n°971006 - Marie-Galante Nuit Tel Garde SAINT LOUIS Tel 0590970365 0590970365 Fax 0590971318 -

Vieux-Fort Clocher De L’Eglise Saint-Albert BEAUSOLEIL Lotissement Beausoleil Festival De La Broderie D Rue E M a Z

IMMOBILIER A B C D E F G H 1 Anse Dupuy Batterie du Phare Hôtel de Ville Eglise Saint-Albert Monument aux morts DUBOIS EHPAD MATOUBA Voie communale DUPRÉ D 6 5 6 Masques de Vieux-Fort Clocher de l’Eglise Saint-Albert BEAUSOLEIL Lotissement Beausoleil Festival de la Broderie d Rue e M a z a r i Anse n Dupuy 2 é r l p lei u LA CASE so D 5 au e STYLISME - COUTURE Be d de e te ut uy u o p Ro R u LHOMEOdeMICHEL 4 AMBULANCE D STYLISTE - Conseil et création se n ’A l n Fabrication de vêtements sur mesure e d n e Création de modèles destinés aux t AMBULANCE u R o manifestations artistiques o R u DUPUY t n e a é Cours d’artisanat textile b r [email protected] d p e u u o D T t e TRANSPORTS SANITAIRES ib a Route d Atelier Couture Route de Beausoleil 97141 Vieux -Fort 0690 41 04 04 o Buste de Delgrès M i live s e l’O d 6 e e LOCATION TOURISTIQUE lle d t Rue u upuy o STADE nse D R 0590 92 01 81 de l’A SORET MICHINEAU Gîtes 3 gîtes créoles d’exception Route 0690 39 78 05 Racines é Zel Piscine 3 Vue mer er CENTRE DE R erci Table d’hôtes ue M BRODERIE 1 Je TIBOIS BIBLIOTHÈQUE uno an-Franç Br e ois Houelc MUNICIPALE Rue ar he tte Ph LA POSTE rd ole [email protected] 0690 68 79 36 a Rig du g e la Fax : 0590 92 08 15 e 4 o Rue d Route de Beausoleil 97141 Vieux -Fort www.racines - e- zel.com facebook : Racines é Zel u B R in e FORT L’OLIVE l Ruelle in [email protected] ide v 7 P. -

Guide Info-Femmes

1 Sommaire Organismes Sanitaires et Sociaux ........................ 4-5 Information sur le Handicap ................................ 6-7 Prévention et Lutte contre les IST et VIH .............. 8-9 Lutte contre l’Exclusion ....................................... 10-11 Lutte contre les Violences faites aux Femmes ....... 12-17 Lutte contre les Addictions .................................. 18-19 2 Accès au Droit ..................................................... 20-22 Droit à l’Emploi ................................................... 22-24 Droit au Logement ............................................... 25-26 Cohésion sociale, sports santé ............................. 27 3 Organismes Sanitaires et Sociaux ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• CGSS CAF Caisse Générale de Sécurité Sociale Caisse d’Allocations Familiales BP 9 Améliorer le cadre de vie, faciliter les loisirs, ré- 97181 Abymes Cedex pondre aux diffi cultés fi nancières, favoriser l’équi- Tél : 0590 90 57 79 libre familial. Email : wwwcgss-guadeloupe.fr Attribuer des prestations familiales Accueil, prise en charge des demandes des Tél : 0810 25 97 10 (prix d’un appel local) usagers pour les problèmes concernant la Horaire d’appel de 7h30 - 13h30 sécurité sociale: maladie, accident de travail, vieillesse, régime général et agricole. - Zac de Dothémare Parc d’activité de providence 97139 Les Abymes - Quartier de l’hôtel de ville 97159 POINTE-À-PITRE Cedex 4 Centre Communal d’Action Sociale Information de proximité, assistance aux personnes défavorisées, attribution d’aides de pre- mière nécessité, instruction de dossier d’aide sociale. Contact : Mairie du domicile Permanence des Travailleurs Sociaux AGREXAM - CENTRE D’EXAMEN DE SANTE Prévention, bilan de santé gratuit (dépistage d’affections diverses, analyse de sang, d’urine, contrôle de tension artérielle, de vue, d’audition, examen dentaire, questionnaire médical) 512 résidences Ciboneye BP 86 97153 POINTE-A-PITRE Tél : 0590 90 49 96 Plusieurs centres de soins fonctionnent sur le territoire. -

The 2018 Unrest Phase at La Soufrière of Guadeloupe (French West Indies) Andesitic Volcano: Scrutiny of a Failed but Prodromal Phreatic Eruption

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 393 (2020) 106769 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores The 2018 unrest phase at La Soufrière of Guadeloupe (French West Indies) andesitic volcano: Scrutiny of a failed but prodromal phreatic eruption Roberto Moretti a,b,⁎, Jean-Christophe Komorowski a, Guillaume Ucciani a,b,SéverineMounea,b,c, David Jessop a,b,c, Jean-Bernard de Chabalier a, François Beauducel a,d, Magali Bonifacie a,b, Arnaud Burtin a,b, Martin Vallée a, Sebastien Deroussi a,b, Vincent Robert a,b, Dominique Gibert e, Tristan Didier a,b, Thierry Kitou a,b, Nathalie Feuillet a,PatrickAllarda, Giancarlo Tamburello f, Tara Shreve a, Jean-Marie Saurel a, Arnaud Lemarchand a, Marina Rosas-Carbajal a, Pierre Agrinier a, Anne Le Friant a, Marc Chaussidon a a Université de Paris, Institut de physique du globe de Paris, CNRS, F-75005 Paris, France b Observatoire volcanologique et sismologique de Guadeloupe, Institut de physique du globe de Paris, F-97113 Gourbeyre, France c Université Clermont Auvergne, CNRS, IRD, OPGC, Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, F-63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France d Institut des Sciences de la Terre - Institut de Recherche pour le Développement - BPPTKG - PVMBG Badan Geologi, Yogyakarta, Indonesia e Geosciences Rennes UMR 6118 - Univ. Rennes I, Rennes, France f Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia sezione di Bologna, via Donato Creti, Bologna, Italy article info abstract Article history: After 25 years of gradual increase, volcanic unrest at La Soufrière of Guadeloupe reached its highest seismic en- Received 17 June 2019 ergy level on 27 April 2018, with the largest felt volcano-tectonic (VT) earthquake (ML 4.1 or MW 3.7) recorded Received in revised form 3 January 2020 since the 1976–1977 phreatic eruptive crisis. -

Lloret, E., Dessert, C., Buss, HL, Chaduteau, C., Huon, S., Alberic, P

Lloret, E., Dessert, C., Buss, H. L., Chaduteau, C., Huon, S., Alberic, P., & Benedetti, M. F. (2016). Sources of dissolved organic carbon in small volcanic mountainous tropical rivers, examples from Guadeloupe (French West Indies). Geoderma, 282, 129-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.07.014 Peer reviewed version License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.07.014 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Elseiver at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016706116303081. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Sources of dissolved organic carbon in small volcanic mountainous tropical rivers, examples from Guadeloupe (French West Indies). Emily LLORETa,b,*, Céline DESSERTb,c,d, Heather L. BUSSe, Carine CHADUTEAUb, Sylvain HUONf, Patrick ALBERICg, Marc F. BENEDETTIb a Laboratoire de Génie Civil et géo-Environnement (LGCgE), Université Lille 1, 59655 Villeneuve d’Ascq, France. b Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP), Sorbonne Paris Cité, Université Paris- Diderot, UMR 7154, CNRS, 75205 Paris, France. c Observatoire de l’Eau et de l’Erosion aux Antilles (OBSERA), IPGP, UMR 7154, CNRS, 75205 Paris, France. -

La Région Guadeloupe Mène Une Politique Énergétique Volontariste

INAUGURATION DU NOUVEAU PARC D’ÉCLAIRAGE PUBLIC DE LA COMMUNE DE GOURBEYRE MOT DU PRESIDENT Après avoir personnellement lancé les travaux aux côtés de Monsieur le Maire, c'est une grande satisfaction de voir se concrétiser ce beau projet, que nous avons pensé avec les communes, pour que l’éclairage public communal retrouve ses lettres de noblesses. Je suis heureux de pouvoir procéder, à l’inauguration du nouveau parc d’éclairage public de cette belle commune de Gourbeyre, car cette belle opération permet de réduire de 60% les consommations d’électricité des communes. A travers notre engagement, la Région Guadeloupe avec ses partenaires que sont l’ADEME, EDF et l’Etat s’appuie sur ses ressources naturelles, sur son expertise et sur sa capacité d’innovation, pour développer une économie décarbonnée et s’inscrire définitivement dans la transition énergétique fors des technologies performantes que nous déployons, et des grands projets en cours sur le territoire, nous ferons de toute la Guadeloupe, un territoire exemplaire. Cette opération s'inscrit dans un large projet de rénovation de plus de 75 000 points lumineux avec des technologies performantes pour toutes les communes de Guadeloupe pour un investissement de l'Europe de plus de 28 millions d'euros en trois ans. Il nous tient particulièrement à cœur que la transition énergétique se traduise par une amélioration continue des services rendus au Guadeloupéen ! Ary Chalus COMMUNIQUE DE PRESSE MODERNISATION DE L’ÉCLAIRAGE PUBLIC La région Guadeloupe mène une politique énergétique volontariste, visant le développement des énergies renouvelables et une meilleure maîtrise de nos consommations d’énergie.