World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rn2 Rehabilitation (Section Ndioum-Bakel) and Construction and Maintenance of Roads on the Morphil Island

THE AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : RN2 REHABILITATION (SECTION NDIOUM-BAKEL) AND CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF ROADS ON THE MORPHIL ISLAND COUNTRY : SENEGAL SUMMARY OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Project Team A.I. MOHAMED, Senior Transport Economist, OITC1/SNFO M. A. WADE, Infrastructure Specialist, OITC/SNFO M.L. KINANE, Senior Environmentalist, ONEC.3 S. BAIOD, Environmentalist Consultant, ONEC.3 P.H. SANON, Socio-economist Consultant, ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Manager: A. OUMAROU Regional Manager: A. BERNOUSSI Resident Representative : M. NDONGO Division Head: J.K. KABANGUKA 1 Rehabilitation of the RN2 (Ndioum-Bakel section ) and roads SUMMARY OF the ESIA enhancement and asphalting in the Morphil Island Project title : RN2 REHABILITATION (SECTION NDIOUM-BAKEL) AND CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF ROADS ON THE MORPHIL ISLAND Country : SENEGAL Project number : P-SN-DB0-021 Department : OITC Division : OITC.1 1 INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for the RN2 and RR40 Roads Development and Pavement Project on the Morphil Island. This summary has been prepared in accordance with the environmental and social assessment guidelines and procedures of the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the Senegalese Government for Category 1 projects. The ESIA was developed in 2014 for all road projects and updated in 2015. This summary has been prepared based on environmental and social guidelines and procedures of both countries and the Integrated Backup System of the African Development Bank. It begins with the project description and rationale, followed by the legal and institutional framework in Senegal. A brief description of the main environmental conditions of the project and comparative technical, economic, environmental and social feasibility are then presented. -

Progress Report for Processing Part of Mali/USAID-INTSORMIL Project

Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Annual Report October 1, 2010 – September 30, 2011 USAID/EGAT/AG/ATGO/Mali Cooperative Agreement # 688-A-00-007-00043-00 Submitted to the USAID Mission, Mali by Management Entity Sorghum, Millet and Other Grains Collaborative Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) Leader with Associates Award: EPP-A-00-06-00016-00 INTSORMIL University of Nebraska 113 Biochemistry Hall P.O. Box 830748 Lincoln, NE 68583-0748 USA [email protected] Table of Contents Page 1. Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 2. Introduction 5 3. Executive Summary of Achievements 8 4. Project component description and intermediate results 9 5. Achievements 11 Production-Marketing 11 Food Processing 12 Décrue Sorghum 14 Training 15 6. Indicators 19 7. Gender related achievements 23 8. Synergic activities 24 9. Other important activities 26 10. Problems/challenges and solutions 27 11. Success stories 32 12. Lessons learned 33 13. Annexes 34 2 Production-Marketing Décrue sorghum Processing Training 3 1. Acronyms and Abbreviations Acronym Description AMEDD Association Malienne d’Eveil au Developpement BNDA Banque Nationale de développement Agricole Mali CONFIGES NGO/ Gao CRRA Centre regional de Recherche Agronomique DRA Division de la Recherche Agronomique FCFA Franc CFA Ha Hectare IER Institut d’Economie Rurale IICEM Integrated Initiatives for Economic Growth In Mali LTA Laboratoire d’Tecnologie Alimentaire (IER) MOU Memorandum of Understanding MT Metric tonne NGO Non Governmental Organization RCGOP NGO/ Tomboctou SAA Sasakawa Foundation WFP World Food Program WTAMU West Texas A&M University 4 The goal of this project is to raise farmers’ incomes in a sustainable way. -

Evaluation of the Project to Strengthen Mother and Child Health and Health Information Systems (Pasmesiss) Government-To-Governm

PERFORMANCE EVALUATION EVALUATION OF THE PROJECT TO STRENGTHEN MOTHER AND CHILD HEALTH AND HEALTH INFORMATION SYSTEMS (PASMESISS) GOVERNMENT-TO-GOVERNMENT FIXED-AMOUNT REIMBURSEMENT AGREEMENT FEBRUARY 2018 This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by Peter Cleaves, Lisa Slifer Mbacké, Mamadou Fall, Ndaté Guèye, Déguène Pouye and Mame Aïssatou Mbaye of Management Systems International, A Tetra Tech Company, for the USAID/Senegal Monitoring and Evaluation Project. EVALUATION OF THE PROJECT TO STRENGTHEN MOTHER AND CHILD HEALTH AND HEALTH INFORMATION SYSTEMS (PASMESISS) GOVERNMENT-TO- GOVERNMENT FIXED-AMOUNT REIMBURSEMENT AGREEMENT Revised February 2018 Contracted under AID-685-C-15-00003 USAID Senegal Mission-Wide Monitoring and Evaluation Project Cover Photo: A mother with her child in Kaffrine Regional Hospital for a consultation. Credit: USAID/Senegal Monitoring and Evaluation Project DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................................................ii Acronyms .......................................................................................................................................iii Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions

Government of Senegal COMPREHENSIVE FOOD SECURITY AND VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS (CFSVA) Livelihood Zone Descriptions WFP/FAO/SE-CNSA/CSE/FEWS NET Introduction The WFP, FAO, CSE (Centre de Suivi Ecologique), SE/CNSA (Commissariat National à la Sécurité Alimentaire) and FEWS NET conducted a zoning exercise with the goal of defining zones with fairly homogenous livelihoods in order to better monitor vulnerability and early warning indicators. This exercise led to the development of a Livelihood Zone Map, showing zones within which people share broadly the same pattern of livelihood and means of subsistence. These zones are characterized by the following three factors, which influence household food consumption and are integral to analyzing vulnerability: 1) Geography – natural (topography, altitude, soil, climate, vegetation, waterways, etc.) and infrastructure (roads, railroads, telecommunications, etc.) 2) Production – agricultural, agro-pastoral, pastoral, and cash crop systems, based on local labor, hunter-gatherers, etc. 3) Market access/trade – ability to trade, sell goods and services, and find employment. Key factors include demand, the effectiveness of marketing systems, and the existence of basic infrastructure. Methodology The zoning exercise consisted of three important steps: 1) Document review and compilation of secondary data to constitute a working base and triangulate information 2) Consultations with national-level contacts to draft initial livelihood zone maps and descriptions 3) Consultations with contacts during workshops in each region to revise maps and descriptions. 1. Consolidating secondary data Work with national- and regional-level contacts was facilitated by a document review and compilation of secondary data on aspects of topography, production systems/land use, land and vegetation, and population density. -

Les Resultats Aux Examens

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT B.P. 5005 - Dakar-Fann – Sénégal Tél. : (221) 338593660 - (221) 338249592 - (221) 338246581 - Fax (221) 338646739 Serveur vocal : 886281212 RESULTATS DU BACCALAUREAT SESSION 2017 Janvier 2018 Babou DIAHAM Directeur de l’Office du Baccalauréat 1 REMERCIEMENTS Le baccalauréat constitue un maillon important du système éducatif et un enjeu capital pour les candidats. Il doit faire l’objet d’une réflexion soutenue en vue d’améliorer constamment son organisation. Ainsi, dans le souci de mettre à la disposition du monde de l’Education des outils d’évaluation, l’Office du Baccalauréat a réalisé ce fascicule. Ce fascicule représente le dix-septième du genre. Certaines rubriques sont toujours enrichies avec des statistiques par type de série et par secteur et sous - secteur. De même pour mieux coller à la carte universitaire, les résultats sont présentés en cinq zones. Le fascicule n’est certes pas exhaustif mais les utilisateurs y puiseront sans nul doute des informations utiles à leur recherche. Le Classement des établissements est destiné à satisfaire une demande notamment celle de parents d'élèves. Nous tenons à témoigner notre sincère gratitude aux autorités ministérielles, rectorales, académiques et à l’ensemble des acteurs qui ont contribué à la réussite de cette session du Baccalauréat. Vos critiques et suggestions sont toujours les bienvenues et nous aident -

Z I G U I N C H O R 2 0

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi ------------------ MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN Z ------------------ AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE I ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE ----------------- G Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Ziguinchor U I N C H O R 2 0 SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET SOCIALE REGIONALE 1 2016 6 Octobre 2019 COMITE DE DIRECTION Directeur Général BABACAR NDIR Directeur Général Adjoint ALLÉ NAR DIOP Conseiller à l’Action Régionale MAMADOU DIENG Président du CLV SECKENE SENE COMITE DE REDACTION Chef du Service Régional Jean Rodrigue MALOU Adjoint au Chef du Service Régional Alassane AW Le point focal du siège qui a aidé à la rédaction de Bintou Diack Ly la SESR COMITE DE LECTURE ET DE VALIDATION SECKENE SENE DIRECTION GENERALE AMADOU FALL DIOUF CPCCI SERGE MANEL DSDS IDRISSA DIAGNE ENSAE MAMADOU BALDE ENSAE OMAR SENE ENSAE AWA CISSOKHO FAYE DSDS MM. RAMLATOU DIALLO DSECN MANDY DANSOKHO ENSAE MAMADOU DIENG CAR NDEYE BINTA DIEME COLY DSDS MAMADOU AMOUZOU OPCV ADJIBOU OPPAH BARRY OPCV BINTOU DIACK LY DSECN MAMADOU BAH DMIS EL HADJI MALICK GUEYE DMIS ABDOULAYE TALL OPCV MOMATH CISSE CGP MAHMOUTH DIOUF DSDS MORY DIOUSS DSDS ATOUMANE FALL DSDS ALAIN FRANCOIS DIATTA DMIS SES de Ziguinchor, Ed. 2016 AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE Rocade Fann –Bel-air–Cerf-volant – Dakar Sénégal. B.P. 116 Dakar R.P. - Sénégal Téléphone (221) 33 869 21 39 - Fax (221) 33 824 36 15 Site web : www.ansd.sn ; Email: [email protected] Distribution : Division de la Documentation, de la Diffusion et des Relations avec les Usagers Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Ziguinchor Adresse : Tilene Complémentaire Tél : 33 991 12 58 B.P. -

An Introduction Into Primary School Education in Senegal

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gönsch, Iris; Graef, Steffen Working Paper Education for all and for life? An introduction into primary school education in Senegal Discussion Paper, No. 55 Provided in Cooperation with: Justus Liebig University Giessen, Center for international Development and Environmental Research (ZEU) Suggested Citation: Gönsch, Iris; Graef, Steffen (2011) : Education for all and for life? An introduction into primary school education in Senegal, Discussion Paper, No. 55, Justus-Liebig- Universität Gießen, Zentrum für Internationale Entwicklungs- und Umweltforschung (ZEU), Giessen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/74445 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents -

Productive Strategies for Poor Rural Households to Participate

Productive Strategies for Poor Households to Participate Successfully in Global Economic Processes First draft Country Report for Senegal to the IDRC By Bara Gueye1 1 INTRODUCTION Objective The overall objective of the study is to prepare an agenda of priority research for the IDRC Rural Poverty and Environment Programme Initiative (RPE) within the theme “productive strategies for poor households to participate successfully in the global economic process”. The RPE’s mission is to contribute to the development of networks, partnerships and communities of practices, in order to strengthen institutions, policies and practices that enhance the food, water and income security of the poor, including those living in fragile or degraded uplands and coastal ecosystems. Short description of the methodology; The methodological process used to carry out this study combined a set of 4 complementary phases: 1 An inception phase aimed at refining the conceptual framework of the study, defining the research scope, carrying out a literature review and drafting an inception report to inform the following phases 2 Six regional scans carried through desk reviews to have an overview of socio-economic development issues of relevance of the study and to identify relevant themes that can potentially feed into regional research agendas. Identification of current research and potential partner institutions was also part of the regional scans. 3 Country level investigations carried in the pilot countries selected in each one of the six sub- regions. Country case studies were based on participatory stakeholders’ analysis with the aim of validating the regional scans reviews. An important component of the country case studies was to make an assessment of the relevance of the research themes and if necessary to propose new themes. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURE GLOBAL PRACTICE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized SENEGAL AGRICULTURAL SECTOR RISK ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized Stephen D’Alessandro, Amadou Abdoulaye Fall, George Grey, Simon Simpkin, and Abdrahmane Wane WORLD BANK GROUP REPORT NUMBER 96296-SN AUGUST 2015 Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURE GLOBAL PRACTICE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PAPER SENEGAL Agricultural Sector Risk Assessment Stephen D’Alessandro, Amadou Abdoulaye Fall, George Grey, Simon Simpkin, and Abdrahmane Wane © 2015 World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org Email: [email protected] All rights reserved This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank Group. The fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank Group or the governments they represent. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank Group concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. World Bank Group encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone: 978-750-8400, fax: 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. -

Senegal: the National Infrastructure Project

INTEGRATING GENDER INTO WORLD BANK FINANCED TRANSPORT PROGRAMS CASE STUDY SENEGAL THE NATIONAL RURAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT (NRIP) PREPARED BY: CODOU BOP JUNE 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The National Rural Infrastructure Project (NRIP) is one component of the rural poverty alleviation strategies implemented by the Senegalese government since the 1990s. In order to put en end to the isolation of rural areas, rural transport has become a priority defined in the rural decentralized development. NRIP is funded by the World Bank, IFAD, the Senegalese State and the beneficiaries. The total amount of the funding is USD 238,900.000 with 63% (USD 151,700 000) brought by the Bank. Its long-term objectives are to reduce poverty in rural areas, improve living conditions of rural populations, promote decentralized rural development and promote good management of local issues. The program concentrates its efforts on building the capacities of collectivities to provide populations with services they themselves have identified. Another goal of the Program is to enable the collectivity in planning and managing their own development programs, collecting funds and generating benefits. As a poverty reduction strategy, the National Rural Infrastructure Programme includes in its first phase a component on rural community roads. NRIP is a twelve-year program from 1998 and to 2011. However, although the implementing phase was scheduled to begin in 2001, the pilot phase is not yet complete due to delays in finance processing in the World Bank as well as the Ministry of Finance in Senegal. GENDER DIFFERENCES IN THE PROJECT’S OUTCOMES In rural areas mobility is an important issue for women. -

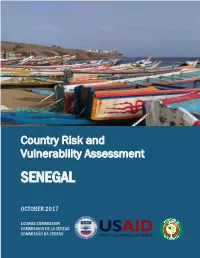

CRVA Report – Senegal

Country Risk and Vulnerability Assessment SENEGAL OCTOBER 2017 ECOWAS COMMISSION COMMISSION DE LA CEDEAO COMMISSÃO DA CEDEAO Country Risk and Vulnerability Assessment: Senegal | 1 DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Cover photo by Pshegubj, accessed via Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fishing_boats_in_Dakar.jpg). Reproduced under Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0. Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations .....................................................................................................................................5 Message from the President of the ECOWAS Commission ........................................................................................7 Statement from the Vice President of the ECOWAS Commission .............................................................................8 Preface ........................................................................................................................................................................9 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 Research Process ................................................................................................................................................ -

Report on Language Mapping in the Regions of Fatick, Kaffrine and Kaolack Lecture Pour Tous

REPORT ON LANGUAGE MAPPING IN THE REGIONS OF FATICK, KAFFRINE AND KAOLACK LECTURE POUR TOUS Submitted: November 15, 2017 Revised: February 14, 2018 Contract Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00055/AID-685-TO-16-00003 Activity Start and End Date: October 26, 2016 to July 10, 2021 Total Award Amount: $71,097,573.00 Contract Officer’s Representative: Kadiatou Cisse Abbassi Submitted by: Chemonics International Sacre Coeur Pyrotechnie Lot No. 73, Cite Keur Gorgui Tel: 221 78585 66 51 Email: [email protected] Lecture Pour Tous - Report on Language Mapping – February 2018 1 REPORT ON LANGUAGE MAPPING IN THE REGIONS OF FATICK, KAFFRINE AND KAOLACK Contracted under AID-OAA-I-14-00055/AID-685-TO-16-00003 Lecture Pour Tous DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publicapublicationtion do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States AgenAgencycy for International Development or the United States Government. Lecture Pour Tous - Report on Language Mapping – February 2018 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 2. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 12 3. STUDY OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 14 3.1. Context of the study ............................................................................................................. 14 3.2.