Tese De Doutorado (2.927Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphological and Molecular Identification of Isospora

Acta Protozool. (2019) 58: 17–23 www.ejournals.eu/Acta-Protozoologica ACTA doi:10.4467/16890027AP.19.007.10838 PROTOZOOLOGICA Morphological and Molecular Identification of Isospora sepetibensis (Chromista: Miozoa: Eimeriidae) from a New Host, Trichothraupis melanops (Passeriformes: Thraupidae: Tachyphoninae) in South America Jhon Lennon GENOVEZ-OLIVEIRA1, Sergian V. CARDOZO2, Águida A. de OLIVEIRA3, Viviane M. de LIMA3, Ildemar FERREIRA3, Bruno P. BERTO3 1 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), Brazil 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biomedicina Translacional, Universidade do Grande Rio, Rua Professor José de Souza Herdy 1160, 25071-202 Duque de Caxias, RJ, Brazil 3 Departamento de Biologia Animal, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, UFRRJ, RJ, Brazil Abstract. Isospora sepetibensis Berto, Flausino, Luz, Ferreira and Lopes, 2008 is a protozoan coccidian parasite (Chromista: Miozoa: Coc- cidiomorphea: Coccidia) that was originally described from Brazilian tanagers Ramphocelus bresilius (Linnaeus, 1766) in the Marambaia Island in the Coast of the State of Rio de Janeiro. In the current work, this species was identified from black-goggled tanagersTrichothraupis melanops (Vieillot, 1818) in the Itatiaia National Park, which is a protected area with a high degree of vulnerability in the interior of the State of Rio de Janeiro, distant in more than 100 km of the type-locality. Its oocysts are sub-spherical to elongate ovoidal, 25.9 × 20.7 µm with smooth, bi-layered wall, ~ 1.3 µm and length/width ratio of 1.1–1.4 (1.26). Micropyle and oocyst residuum absent, but one or two polar granules are present. -

Southeastern Brazil: Best of the Atlantic Forest

SOUTHEASTERN BRAZIL: BEST OF THE ATLANTIC FOREST OCTOBER 8–22, 2017 A trip first, the rarely seen Buff-fronted Owl – Photo: Andrew Whittaker LEADER : ANDREW WHITTAKER LIST COMPILED BY : ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS , INC . 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE , SUITE 1003 AUSTIN , TEXAS 78746 WWW .VENTBIRD .COM SOUTHEASTERN BRAZIL: BEST OF THE ATLANTIC FOREST OCTOBER 8–22, 2017 By Andrew Whittaker Once again, our Brazilian flagship tour visiting the lovely southeast rocked, delivering a bonanza of Atlantic Forest endemics, spectacular scenery, all-around great birding, and wonderful Brazilian cuisine that we have come to expect from this fantastic biologically rich region. First and foremost we tallied 391 species , a whopping 140 of which were regional and/or Brazilian endemics! These figures become all the more impressive when you consider that many of the wider ranging species not included as “endemics” in the preceding tallies are represented in southeast Brazil by distinctive subspecies endemic to the Atlantic Forest region, and that at least 15–25 of these subspecies that we recorded during our tours are likely to be elevated to separate species status in the near future! Beginning in São Paulo, our first destination was Intervales State Park, my own personal favorite among the many great birding spots included in our southeast Brazil trip. Intervales never fails to deliver a huge serving of Atlantic Forest endemics and just plain fantastic birding experiences, and such was the case again this trip. We began the first evening with one of my personal highlights, the fabulous and incredibly cooperative male Long-trained Nightjar . In fact, the male Long-trained Nightjars put on a show for us on two consecutive nights, treating us to multiple close passes, with two males chasing each other just above our heads. -

Adrenal and Thyroid Weights in Birds

July• 397 1961] ADRENAL AND THYROID WEIGHTS IN BIRDS FRANK A. I•ARTMAN AND t•ATItARINE A. BROWNELL LITTLE studyhas beenmade of the relative sizesof adrenaland thy- roid glandsin different speciesof birds. One of us (Hartman, 1946) reported such a study on birds collectedin the United States some years ago. In this paper, resultson birds collectedin Panamainclude a numberof familiesand speciesnot found in the United States, some migrants from the United States, and two domesticspecies, Gallus gallus and Coturnix coturnix. Data from 249 speciesin 49 familiesare reported. Specimenswere obtained during Decemberand January near sea level on the Rio Chagresand during February and March at 1,300 meters elevation near the villageof E1 VolcAnin the Provinceof Chiriqui. This material was also usedto study the musclesof locomotionas well as to furnish skins of the rare forms. METHODS All specimenswere kept in plastic,waterproof bags to preventdrying until weighed at the field station. Small birds were weighed on a torsionbalance of 120 gramscapacity. Larger oneswere weighedon Chatilion spring balances,the most sensitiveone for the weight in- volved being used: 6,000 grams capacitywith 24 grams sensitivity; 500 gramscapacity with 10 gramssensitivity; and 250 gramscapacity with 5 grams sensitivity. The adrenalsand thyroids were carefully dissectedfree of extraneoustissue with the aid of a binocularloupe and promptlyweighed on a Roller-Smith balanceof either 30 mg. or 1,500 mg. capacity,depending upon the size of the specimen.The thorough- ness of the dissectionis extremely important becausemore or less extraneoustissue may adhereto the gland,especially the adrenal,thus contributingto the error. Only birdsof healthyappearance were used. Most birds were collected between 0700 and 1100. -

TOP BIRDING LODGES of PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society

TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA WITH IOS: JUNE 26 – JULY 5, 2018 TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society June 26-July 5, 2018 Guides: Adam Sell and Josh Engel with local guides Check out the trip photo gallery at www.redhillbirding.com/panama2018gallery2 Panama may not be as well-known as Costa Rica as a birding and wildlife destination, but it is every bit as good. With an incredible diversity of birds in a small area, wonderful lodges, and great infrastructure, we tallied more than 300 species while staying at two of the best birding lodges anywhere in Central America. While staying at Canopy Tower, we birded Pipeline Road and other lowland sites in Soberanía National Park and spent a day in the higher elevations of Cerro Azul. We then shifted to Canopy Lodge in the beautiful, cool El Valle de Anton, birding the extensive forests around El Valle and taking a day trip to coastal wetlands and the nearby drier, more open forests in that area. This was the rainy season in Panama, but rain hardly interfered with our birding at all and we generally had nice weather throughout the trip. The birding, of course, was excellent! The lodges themselves offered great birding, with a fruiting Cecropia tree next to the Canopy Tower which treated us to eye-level views of tanagers, toucans, woodpeckers, flycatchers, parrots, and honeycreepers. Canopy Lodge’s feeders had a constant stream of birds, including Gray-cowled Wood-Rail and Dusky-faced Tanager. Other bird highlights included Ocellated and Dull-mantled Antbirds, Pheasant Cuckoo, Common Potoo sitting on an egg(!), King Vulture, Black Hawk-Eagle being harassed by Swallow-tailed Kites, five species of motmots, five species of trogons, five species of manakins, and 21 species of hummingbirds. -

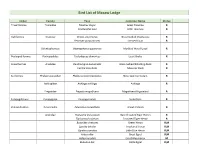

Bird List of Macaw Lodge

Bird List of Macaw Lodge Order Family Taxa Common Name Status Tinamiformes Tnamidae Tinamus major Great Tinamou R Crypturellus soul Little Tinamou R Galliformes Cracidae Ortalis cinereiceps Gray-headed Chachalaca R Penelope purpurascens Crested Guan R Odontophoridae Odontophorus gujanensis Marbled Wood-Quail R Podicipediformes Podicipedidae Tachybaptus dominicus Least Grebe R Anseriformes Anatidae Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied Whistling-Duck R Cairina moschata Muscovy Duck R Suliformes Phalacrocoracidae Phalacrocorax brasilianus Neotropic Cormorant R Anhingidae Anhinga anhinga Anhinga R Fregatidae Fregata magnificens Magnificent Frigatebird R Eurypygiformes Eurypygidae Eurypyga helias Sunbittern R Pelecaniformes Pelecanidae Pelecanus occidentalis Brown Pelican R Ardeidae Tigrisoma mexicanum Bare-throated Tiger-Heron R Tigrisoma fasciatum Fasciated Tiger-Heron R Butorides virescens Green Heron R,M Egretta tricolor Tricolored Heron R,M Egretta caerulea Little Blue Heron R,M Ardea alba Great Egret R,M Ardea herodias Great Blue Heron M Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret R,M Egretta thula Snowy Egret R,M Nyctanassa violacea Yellow-crowned Night-Heron R,M Cochlearius cochlearius Boat-billed Heron R Threskiornithidae Eudocimus albus White Ibis R Mesembrinibis cayennensis Green Ibis R Platalea ajaja Roseate Sponbill R Charadriiformes Charadriidae Vanellus chilensis Southern Lapwing R Charadrius semipalmatus Semipalmated Plover M Recurvirostridae Himantopus mexicanus Black-necked Stilt R,M Scolopacidae Tringa semipalmata Willet M Tringa solitaria -

Panama's Canopy Tower and El Valle's Canopy Lodge

FIELD REPORT – Panama’s Canopy Tower and El Valle’s Canopy Lodge January 4-16, 2019 Orange-bellied Trogon © Ruthie Stearns Blue Cotinga © Dave Taliaferro Geoffroy’s Tamarin © Don Pendleton Ocellated Antbird © Carlos Bethancourt White-tipped Sicklebill © Jeri Langham Prepared by Jeri M. Langham VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DR., AUSTIN, TX 78746 Phone: 512-328-5221 or 800-328-8368 / Fax: 512-328-2919 [email protected] / www.ventbird.com Myriads of magazine articles have touted Panama’s incredible Canopy Tower, a former U.S. military radar tower transformed by Raúl Arias de Para when the U.S. relinquished control of the Panama Canal Zone. It sits atop 900-foot Semaphore Hill overlooking Soberania National Park. While its rooms are rather spartan, the food is Panama’s Canopy Tower © Ruthie Stearns excellent and the opportunity to view birds at dawn from the 360º rooftop Observation Deck above the treetops is outstanding. Twenty minutes away is the start of the famous Pipeline Road, possibly one of the best birding roads in Central and South America. From our base, daily birding outings are made to various locations in Central Panama, which vary from the primary forest around the tower, to huge mudflats near Panama City and, finally, to cool Cerro Azul and Cerro Jefe forest. An enticing example of what awaits visitors to this marvelous birding paradise can be found in excerpts taken from the Journal I write during every tour and later e- mail to participants. These are taken from my 17-page, January 2019 Journal. On our first day at Canopy Tower, with 5 of the 8 participants having arrived, we were touring the Observation Deck on top of Canopy Tower when Ruthie looked up and called my attention to a bird flying in our direction...it was a Black Hawk-Eagle! I called down to others on the floor below and we watched it disappear into the distant clouds. -

Annual Patterns of Molt and Reproductive Activity of Passerines

Annual Patterns of Molt and Reproductive Activity of Passerines in South-Central Brazil Author(s) :Miguel  Marini and Renata Durães Source: The Condor, 103(4):767-775. 2001. Published By: Cooper Ornithological Society DOI: URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1650/0010-5422%282001%29103%5B0767%3AAPOMAR %5D2.0.CO%3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. The Condor 103:767±775 q The Cooper Ornithological Society 2001 ANNUAL PATTERNS OF MOLT AND REPRODUCTIVE ACTIVITY OF PASSERINES IN SOUTH-CENTRAL BRAZIL MIGUEL Aà .MARINI1 AND RENATA DURAÄ ES Departamento de Biologia Geral, ICB-Instituto de CieÃncias BioloÂgicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, C.P. 486, 30161-970, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil Abstract. We analyzed the occurrence of molt and brood patches in resident passerines from four localities in south-central Brazil. -

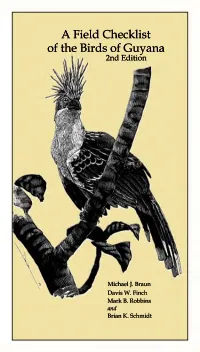

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2Nd Edition

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition Michael J. Braun Davis W. Finch Mark B. Robbins and Brian K. Schmidt Smithsonian Institution USAID O •^^^^ FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition by Michael J. Braun, Davis W. Finch, Mark B. Robbins, and Brian K. Schmidt Publication 121 of the Biological Diversity of the Guiana Shield Program National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC, USA Produced under the auspices of the Centre for the Study of Biological Diversity University of Guyana Georgetown, Guyana 2007 PREFERRED CITATION: Braun, M. J., D. W. Finch, M. B. Robbins and B. K. Schmidt. 2007. A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana, 2nd Ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. AUTHORS' ADDRESSES: Michael J. Braun - Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD, USA 20746 ([email protected]) Davis W. Finch - WINGS, 1643 North Alvemon Way, Suite 105, Tucson, AZ, USA 85712 ([email protected]) Mark B. Robbins - Division of Ornithology, Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 66045 ([email protected]) Brian K. Schmidt - Smithsonian Institution, Division of Birds, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC, USA 20013- 7012 ([email protected]) COVER ILLUSTRATION: Guyana's national bird, the Hoatzin or Canje Pheasant, Opisthocomus hoazin, by Dan Lane. INTRODUCTION This publication presents a comprehensive list of the birds of Guyana with summary information on their habitats, biogeographical affinities, migratory behavior and abundance, in a format suitable for use in the field. It should facilitate field identification, especially when used in conjunction with an illustrated work such as Birds of Venezuela (Hilty 2003). -

Threatened Birds of the Americas

RUSSET-WINGED SPADEBILL Platyrinchus leucoryphus V/R10 Although now being found fairly widely in Rio de Janeiro state following the identification of its call, this Atlantic Forest flycatcher of south-east Brazil, eastern Paraguay and northern Argentina occurs at very low densities and remains very poorly known. It has suffered from habitat destruction and is in urgent need of study. DISTRIBUTION The Russet-winged Spadebill is endemic to the Atlantic Forest region of south-east South America, from Espírito Santo south to northern Rio Grande do Sul (no records from Santa Catarina) in Brazil into eastern Paraguay and north-eastern Argentina. Brazil In the following account, localities are listed from north to south. Espírito Santo The species was included in the state bird list by Ruschi (1953), and a specimen, formerly in MNRJ but now missing, was collected in the state (J. F. Pacheco in litt. 1991, LPG). Recent records are from the Santa Lucia Reserve (700 ha, kept by MNRJ: see Oliver and Santos 1991: 82), Santa Teresa, October 1986 (J. Vielliard verbally 1986), and the Augusto Ruschi (Nova Lombardia) Biological Reserve, 900 m, 1984-1990 (C. E. Carvalho in litt. 1987, TAP), and October 1989 (M. Kessler in litt. 1989). Rio de Janeiro Four old skins in BMNH are labelled “Rio de Janeiro”. This state holds the bulk of modern records, all from the late 1980s and early 1990s (and all supplied by J. F. Pacheco in litt. 1987, 1991): Desengano State Park, at three sites, 500-1,000 m: Morumbeca do Imbé, February to April, October 1987 to 1989, Marreiros, April 1989, and ribeirão Macapá, April 1989; Mata da Cicuta, Volta Redonda, October 1987; Caiçara, Piraí, July 1989, May 1990; Piraí Ecological Station, December 1987; Serra do Mendanha (north of Campo Grande), August 1988; rio Florestão, Angra dos Reis, December 1990; Horto Florestal (adjacent to Tijuca National Park), September 1988; and Sítio Palmeiras, Parati, September 1989, April and November 1990. -

Belize and Mesoamerica Edition) by Victoria D

The Birds Without Borders – Aves Sin Fronteras® Recommendations for Landowners: (Belize and Mesoamerica edition) By Victoria D. Piaskowski, Mario Teul, Reynold N. Cal, Kari M. Williams and David Tzul Dr. Gil Boese, President, Foundation for Wildlife Conservation, Inc. President emeritus, Zoological Society of Milwaukee Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S.A. About the Authors Birds Without Borders - Aves Sin Gil Boese, Ph.D., was president of the Zoological Fronteras® Contact Information Society of Milwaukee for 16 years. He has been president of the Foundation for Wildlife Conservation, Belize: Inc., since its inception in 1993. Dr. Boese initiated Birds Without Borders - Aves Sin Fronteras® the Birds Without Borders - Aves Sin Fronteras® Forest Drive (BWB-ASF) project in 1996 and continues to oversee Help for Progress Building the project. He has supervised the management of P.O. Box 97 Runaway Creek Nature Preserve since its purchase Belmopan City, Cayo District in 1998. Dr. Boese has a Ph.D in pathobiology from Belize, Central America Johns Hopkins University and has done extensive Phone: 501-822-0236 field work in zoology. Fax: 501-822-0241 E-mail: [email protected] Victoria Piaskowski has been the international Wisconsin: coordinator of BWB-ASF since it began in 1996. Birds Without Borders - Aves Sin Fronteras® Throughout the project, she has managed the Foundation for Wildlife Conservation, Inc. research and field work and conducted staff Zoological Society of Milwaukee training. Piaskowski has a master of science 1421 N. Water St. degree in biological sciences from the Milwaukee, WI 53202 University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. USA Phone: 414-276-0339 Mario Teul has been the Belize national coordinator Fax: 414-276-0886 since 2003 and has been with the project since it E-mail: [email protected] started in Belize in 1997. -

Name That Animal Matching Common Names with Scientific Names

Name that animal Matching common names with scientific names High School Objectives Students will learn that all living things are given a two-part Latin or Greek scientific name to avoid Key Words confusion among scientists from different areas of the country and world. genus Students will learn that scientists separate living things into different groups so that they may study species them more easily. Students will learn that the more closely related two animals are the more taxonomic ranks they will both be found in. Standards EL.11.1.2 Background information Scientific names are usually formed from descriptive Latin or Greek words. Scientific names consist of the animal’s genus and species. The genus is the first part of the scientific name. A genus is a group of closely related animals within a family. The genus should start with a capital letter and be italicized or underlined. The species is the second part of the scientific name. A species is the most specialized division. A species name is never capitalized. Procedure Have students determine which scientific names belong with which common names using the Latin and Greek root words sheet. Recommended assessment Ensure that students have the correct answers. Extensions Make flash cards with pictures of animals on one side and their taxonomy on the other. Key 1. Y 2. L 3. J 4. M 5. Q 6. W 7. O 8. K 9. H 10.G 11. P 12. I 13. U 14. S 15.N 16. S 17.R 18. V 19. D 20.E 21. -

On the Standardization of Nest Descriptions of Neotropical Birds

OrnitologiaAA.qxd 15/12/2005 17:40 Page 7 Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 13 (2):143-154 Dezembro 2005 On the standardization of nest descriptions of neotropical birds José Eduardo Simon 1, 2 and Sergio Pacheco 3 1 Museu de Biologia Mello Leitão. R. José Ruschi, 4, Santa Teresa, ES. Brasil. CEP 29650-000. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas/Zoologia. Museu Nacional-UFRJ, Quinta da Boa Vista s/n, Rio de Janeiro, RJ. Bra- sil. CEP 20940-040. 3 Departamento de Biologia Geral, Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Viçosa, MG. Brasil. CEP 36570-000. Recebido em 22 de novembro de 2004; aceito em 11 de agosto de 2005 ABSTRACT. Different authors have used different methods and nomenclatures to describe bird nests of the Neotropical region, leading to mud- dled terminology which makes comparisons among published data difficult. The present study suggests a standardization and a hierarchy of cri- teria which make easier to understand nest structures and allow direct comparisons among data from different authors in reports on bird evolu- tion, conservation, phylogeny, etc. For that, the nest has been defined as any place where the eggs are laid. Four elementary nest standards are proposed: simple (when eggs rest on an unlined or roughly lined floor), cup (any basket or bowl-like form), closed (when the walls completely cover the incubatory chamber), and cavity (when they are placed inside natural or artificial cavities). The simple standard has two variants: un- lined and platform. The cup standard has two variants: high cup and low cup; the closed standard has six variants: long, globular, furnace, irre- gular, ovoid and retort.