The Wind Music of Steve Danyew: a Discussion and Analysis of Three Significant Wind Compositions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Ore Sacre Del Giorno Le Ore Dell’Ufficio Divino Nelle Basiliche Ravennati

Le ore sacre del giorno le ore dell’ufficio divino nelle basiliche ravennati The Tallis Scholars Le ore sacre del giorno le ore dell’ufficio divino nelle basiliche ravennati The Tallis Scholars Eni Partner Principale del Festival di Ravenna 2019 Basiliche della città 16 giugno, dalle ore 00.00 ringrazia Sotto l’Alto Patronato del Presidente della Repubblica Italiana con il patrocinio di Associazione Amici di Ravenna Festival Senato della Repubblica Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Apt Servizi Emilia Romagna Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mare Adriatico Centro-Settentrionale Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale BPER Banca Classica HD Cna Ravenna Confartigianato Ravenna Confindustria Romagna con il sostegno di Consar Group Contship Italia Group Consorzio Integra COOP Alleanza 3.0 Corriere Romagna DECO Industrie Eni Federazione Cooperative Provincia di Ravenna Federcoop Romagna Fondazione Cassa dei Risparmi di Forlì Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Ravenna Fondazione del Monte di Bologna e Ravenna Gruppo Hera con il contributo di Gruppo Mediaset Publitalia ’80 Gruppo Sapir GVM Care & Research Hormoz Vasfi Koichi Suzuki Italdron LA BCC - Credito Cooperativo Ravennate, Forlivese e Imolese La Cassa di Ravenna SpA Legacoop Romagna Mezzo PubbliSOLE Comune di Forlì Comune di Lugo Comune di Russi Publimedia Italia Quick SpA Quotidiano Nazionale Koichi Suzuki Rai Uno Hormoz Vasfi Ravennanotizie.it Reclam Romagna Acque Società delle Fonti Setteserequi partner principale -

Armenian State Chamber Choir

Saturday, April 14, 2018, 8pm First Congregational Church, Berkeley A rm e ni a n State C h am b e r Ch oir PROGRAM Mesro p Ma s h tots (362– 4 40) ༳ཱུའཱུཪཱི འཻའེཪ ྃཷ I Knee l Be for e Yo u ( A hym n f or Le nt) Grikor N ar e k a tsi ( 9 51–1 0 03) གའཽཷཱཱྀུ The Bird (A hymn for Easter) TheThe Bird BirdBir d (A (A(A hymn hymnhym forn for f oEaster) rEaster) East er ) The Bird (A hymn for Easter) K Kom itas (1869–1 935) ཏཷཱྀཿཡ, ོཷཱྀཿཡ K K K Holy, H oly གའཿོའཱུཤའཱུ ཤཿརཤཿ (ཉའཿ ༳) Rustic Weddin g Son g s (Su it e A , 1899 –1 90 1) ༷ཿཱུཪྀ , རཤཾཱུཪྀ , P Prayer r ayer ཆཤཿཪ ེའཱུ འཫའཫ 7KH%UL The B ri de’s Farewell ༻འརཽཷཿཪ ཱིཤཿ , ལཷཛཱྀོ འཿཪ To the B ride g room ’s Mo th er ༻འརཽཷཿ ཡའཿཷཽ 7KH%ULGH The Bridegroom’s Blessing ཱུ༹ ལཪཥའཱུ , BanterB an te r ༳ཱཻུཤཱི ཤཿཨའཱི ཪཱི ུའཿཧ , D ance ༷ཛཫ, ཤཛཫ Rise Up ! (1899 –190 1 ) གཷཛཽ འཿཤྃ ོའཿཤཛྷཿ ེའཱུ , O Mountain s , Brin g Bree z e (1913 –1 4) ༾ཷཻཷཱྀ རཷཱྀཨའཱུཤཿར Plowing Song of Lor i (1902 –0 6) ༵འཿཷཱཱྀུ Spring Song(190 2for, P oAtheneem by Ho vh annes Hovh anisyan) Song for Athene Song for Athene A John T a ve n er (19 44–2 013) ThreeSongSong forfSacredor AtheneAth Hymnsene A Three Sacred Hymns A Three Sacred Hymns A Three Sacred Hymns A Alfred Schn it tke (1 934–1 998) ThreeThree SacredSacred Hymns H ymn s Богородиц е Д ево, ра д уйся, Hail to th e V irgin M ary Господ и поми луй, Lord, Ha ve Mercy MissaОтч Memoriaе Наш, L ord’s Pra yer MissaK Memoria INTERMISSION MissaK Memoria Missa Memoria K K Lullaby (from T Lullaby (from T Sure on This Shining Night (Poem by James Agee) Lullaby (from T SureLullaby on This(from Shining T Night (Poem by James Agee) R ArmenianLullaby (from Folk TTunes R ArmenianSure on This Folk Shining Tunes Night (Poem by James Agee) Sure on This Shining Night (Poem by James Agee) R Armenian Folk Tunes R Armenian Folk Tunes The Bird (A hymn for Easter) K Song for Athene A Three Sacred Hymns PROGRAM David Haladjian (b. -

History of the Stetson University Concert Choir Gregory William Lefils Jr

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 History of the Stetson University Concert Choir Gregory William Lefils Jr. Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC HISTORY OF THE STETSON UNIVERSITY CONCERT CHOIR By GREGORY WILLIAM LEFILS, JR. A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2014 Gregory William LeFils, Jr. defended this dissertation on July 10, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Kevin Fenton Professor Directing Dissertation Christopher Moore University Representative Judy Bowers Committee Member André J. Thomas Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank the many individuals who helped me in the creation of this document. First I would to thank Gail Grieb for all of her help. Her tireless dedication as Stetson University Archives Specialist has been evident in my perusal of the many of thousands of documents and in many hours of conversation. I would also like to thank Dr. Suzanne Byrnes whose guidance and editorial prowess was greatly appreciated in putting together the final document. My thanks go to Dr. Timothy Peter, current director of the Concert Choir, and Dr. Andrew Larson, Associate Director of Choral activities, for their continued support and interest throughout this long process. -

May 2019 New Release Book

May 2019 New Release Book . Contact: Clay Pasternack Gary Davis Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Phone: 440-333-2208 | Fax: 440-333-2280 Phone: 206-972-7257 | Fax: 425-671-0193 21258 Maplewood Avenue Rocky River, Ohio 44116-1244 WRECKLESS ERIC TRANSIENCE KEY SELLING POINTS: SOUTHERN DOMESTIC Eric Goulden, the man everyone knows as Wreckless Eric, is a rare example of an older and established artist who RECORDS hasn't lapsed into comfortable formulas. Exactly a year after his last album, the well-received Construction Time & Demolition, he's back with a new album, Transience. For every song of Wreckless Eric's you remember from his early days on Stiff Records, he's recorded 10 more that you've probably never heard. The early DIY British indie label may have been his entry-level position into the music business, but Eric Goulden didn't stop making music after the novelty of Stiff Records - and his being known as Wreckless Eric - wore off. Forty years on, Goulden is still making insightful music while the original label is but a footnote in music history. On Transience, Eric is joined by friends including acoustic 12-string guitar player Alexander Turnquist, Cheap Trick bassist, Tom Petersson, Amy Rigby on piano and backing TRACK LISTING vocals, jazz horn player Artie Barbato, and on drums Steve Goulding, late of Graham Parker & the Rumour - the first 1. FATHER TO THE MAN time he and Eric have recorded together since Eric's 2. STRANGE LOCOMOTION enduring hit "Whole Wide World" back in 1976. He wrote the songs on the move, alone in grubby rooms, in 3. -

Ausglass Magazine a Quarterly Publication of the Australian Association of Glass Artists Aus Ass

Ausglass Magazine A Quarterly Publication of the Australian Association of Glass Artists aus ass POST CONFERENCE EDITION Registered by Australia Post Publication No. NBG1569 1991 CONTENTS Introduction 3 An Historical Context - by Sylvia Kleinert 5 ausglass The Contemporary Crafts Industry: magazine Its Diversity - by John Odgers u Contemporary Glass - Are We Going the Right Way? - by Robert Bell 15 Dynamic Learning - A Quality Approach to Quality Training - by Richard Hames 17 POST CONFERENCE The Getting of Wisdom: the gaining of EDmON 1991 skills and a philosophy to practice Session 1 - Cedar Prest 20 Session 2 - Bridget Hancock 22 Session 3 - Richard Morrell 23 Session 4 - Anne Dybka 24 New Editorial Committee: Fostering the Environment for Professional Practice - by Noel Frankham 27 Editor Technique and Skill: its use. development Bronwyn Hughes and importance in contemporary glass Letters and correspondence to by Klaus Moje 32 Challenges in Architectural Glass - by Maureen Cahill 35 50 Two Bays Road, Ethics and Survival - by WtuTen Langley 42 Mt. Eliza, VIC. 3930. When is a Chihuly a Billy Morris? - by Tony Hanning 43 Phone: Home - (03) 787 2762 Production Line: A Means to an End - by Helen Aitken-Kuhnen 47 The Artist and the Environment - by Graham Stone 49 Editorial Committee Working to a Brief- Bronwyn Hughes Chairperson Working to a Philosophy - by Lance Feeney 51 Jacinta Harding Secretary A Conflict of Interest - by Elizabeth McClure 53 Mikaela Brown Interstate & The Gift - Contemporary Making - by Brian Hirst 55 O.S. Liaison Meeting Angels: Reconciling Craft Practice Carrie Westcott and Theory - by Anne Brennan 57 Advertising Kim Lester Function? - by Grace Cochrane 6S Juliette Thornton Internationalism in Glass Distnbution Bronwyn Hughes Too Much Common Ground - by Susanne Frantz 67 David Hobday Board Gerie Hermans Members Graham Stone President: Elizabeth McClure FRoNT COVER: C/o Glass Workshop, The Crowning of the new President. -

MISSA WELLENSIS MISSA WELLENSIS Duration, None Longer Than 25 Minutes

MISSA WELLENSIS MISSA WELLENSIS duration, none longer than 25 minutes. These JOHN TAVENER (1944-2013) late-flowering pieces marked a step away from Death came close to John Tavener in December the expansive gestures present in much Missa Wellensis * 2007. The composer, in Switzerland for the of his music of the early 2000s; they also 1 Kyrie [6.06] first performance of his Mass of the encompassed a refinement of Tavener’s 2 Gloria [5.42] Immaculate Conception, was struck by a heart universalist outlook, part of a personal quest 3 Sanctus and Benedictus [3.01] 4 Agnus Dei [2.15] attack that knocked him into a coma for Sophia perennis or the perennial wisdom and demanded emergency surgery. When he common to all religious traditions. 5 The Lord’s Prayer [2.19] regained consciousness, Tavener the convalescent 6 Love bade me welcome [6.02] discovered that the familiar fervour of his The works of Tavener’s final years, including 7 Preces and Responses Part One * [2.07] faith in God was no longer there; he had the Missa Wellensis and Preces and Responses Cantor: Iain MacLeod-Jones (tenor) also lost his desire to write music. Tavener’s for Wells Cathedral, were driven by an intention 8 Psalm 121: I Will Lift up Mine Eyes unto the Hills [5.17] long recovery at home, a trial endured for to recover the essence of sacred or spiritual Magnificat and Nunc dimittis ‘Collegium Regale’ three years, was marked by physical weakness texts, to renew their vitality and immediacy, 9 Magnificat [7.25] and extreme pain and their correlates, to connect with their deepest claims to truth. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

A Celebration of Women in Song Music By, About & for Women

PRESENTS A CELEBRATION OF WOMEN IN SONG Music By, About & For Women Directed by Paul Thompson Sunday, November 15th, 2015 at 1:00 pm Mount Calvary Lutheran Church | Boulder CantabileSingers.org A CELEBRATION OF WOMEN IN SONG PROGRAM A Song by Anna Amalia Herzogen von Sachsen Regina Coeli Laetare Amalia Herzogen von Sachen (1739-1807) Soloists: Jenifer Burks, Lucy Kelly, Ben Herbert, Tom Voll Cellist: Libby Murphy Songs for Queen Elizabeth I Triumphs of Oriana All Creatures Now Are Merry-Minded John Bennet (1575–1614) As Vesta Was Thomas Weelkes (1576–1623) Fair Nymphs, I Heard One Telling John Farmer (1570?–1601) Songs by Fanny Hensel Gartenlieder, Op. 3 Fanny Hensel (1805–1847) No. 2 Schöne Fremde No. 5 Abendlich Schon Rauscht Der Wald No. 4 Morgengruß A Song about Mary the Mother Totus Tuus Henryk Górecki (1933–2010) INTERMISSION A Song about the Feminine Imbolc from Wheel of the Year, a Pagan Song Cycle Leanne Daharja Veitch (b. 1970) Soloist: Hari Baumbach Cellist: Libby Murphy Songs for Athene, the goddess, princess, and companion Song for Athene John Tavener (1944–2013) Songs about St. Cecilia, the muse Hymn to St. Cecelia, Op. 27 Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) Soloists: SusanWiersema, Katja Stokley, Julien Salmon, Brian Underhill Songs by Gwynthyn Walker How Can I Keep from Singing? Gwyneth Walker (b. 1947) CantabileSingers.org A CELEBRATION OF WOMEN IN SONG TEXTS Regina Coeli Laetare Regina Coeli Laetare Regina coeli, laetare, alleluja. Queen of heaven rejoice! Alleluia! Quia quem meruisti portare, alleluja. For He whom Thou didst merit to bear, alleluia, Resurexit, sicut dixit alleluja. -

2016 SDF 5.5X8.5 NFA Book.Pdf 1 6/24/16 7:56 AM

National Flute Association 44th Annual Convention SanSan Diego,Diego, CACA August 11–14, 2016 SDF_5.5x8.5_NFA_Book.pdf 1 6/24/16 7:56 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K YOUR VOICE ARTISTRY TOOLS SERVICES unparalleled sales, repair, & artistic services for all levels BOOTH 514 www.flutistry.com 44th ANNUAL NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION CONVENTION, SAN DIEGO, 2016 3 nfaonline.org 4 44th ANNUAL NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION CONVENTION, SAN DIEGO, 2016 nfaonline.org 44th ANNUAL NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION CONVENTION, SAN DIEGO, 2016 5 nfaonline.org INSURANCE PROVIDER FOR: ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT FLUTE INSURANCE www.fluteinsurance.com Located in Florida, USA or a Computer Near You! FL License # L054951 • IL License # 100690222 • CA License# 0I36013 6 44th ANNUAL NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION CONVENTION, SAN DIEGO, 2016 nfaonline.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Coordinators ............................................................... 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2016 Awards ..................................................................................... 23 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Award Recipients ....................................................................................... 26 Instrument Security Room Information and Rules and Policies .......... 28 General Hours and Information ........................................................ -

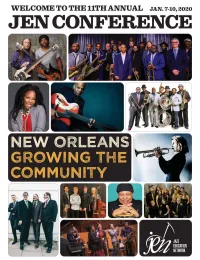

The 2020 Jazz Education Network Conference

THE 2020 JAZZ EDUCATION NETWORK CONFERENCE JEN FEATURES ADONIS ROSE’S NEW ORLEANS! When Adonis Rose took over as artis- tic director of the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra, the group was on the verge of collapse. Through sweat, hard work and lots of faith, the drum- mer/bandleader has the 18-piece group cooking again. Witness them at the JEN Scholarship Concert on Friday night! 38 MEET THE 98 CHECKING IN ARTISTS! WITH ROXY COSS Meet the Artists is a new fea- The wicked good tenor player ture at this year’s JEN con- is also a staunch advocate for ference. During dedicat- equity in jazz. She discusses ed exhibit hours this week, how she founded the Women attendees have an opportu- In Jazz Organization, serves nity to say hello to dozens of on JEN’s Women In Jazz stars from jazz and jazz edu- Committee and strives to help cation. Just head down to create more opportunities for Elite Hall (Level 1)! women on the bandstand! WELCOME TO JEN! JEN CONFERENCE SCHEDULE 10 JEN President’s Welcome 36 Meet the Artists 12 Mayor of New Orleans’ Welcome 38 Hyatt Regency New Orleans Map 14 Meet the Sponsors 40 Tuesday, Jan. 7, Jazz Industry/Music 16 The JEN Board of Directors Business Symposium Schedule 18 JEN Initiatives 42 Tuesday, Jan. 7, JEN Conference Schedule 44 Wednesday, Jan. 8, JEN Conference Schedule 60 Thursday Jan. 9, JEN Conference Schedule Friday, Jan. 10, JEN HONOREES 78 JEN Conference Schedule 22 Scholarship Recipients 24 Composer Showcase Honorees VISIT OUR JEN EXHIBITORS! 26 Sisters In Jazz Honorees 92 Exhibitor List 28 JEN Commissioned Charts 93 Exhibition Hall Map 30 JEN Distinguished Award Honorees 94 JEN Guide Advertiser Index On the cover, clockwise from top left: Bass Extremes with Steve Bailey and Victor Wooten, The New Orleans Jazz Orchestra, the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Bria Skonberg, Western Michigan University’s Gold Company, Chucho Valdés, the ChiArts Jazz Combo, Carmen Bradford and RJAM, Brubecks Play Brubeck, Tia Fuller and Mark Whitfield.