Colocviu Internaţional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Abstracts

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 1 Institute of Archaeology Belgrade, Serbia 24. LIMES CONGRESS Serbia 02-09 September 2018 Belgrade - Viminacium BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Belgrade 2018 PUBLISHER Institute of Archaeology Kneza Mihaila 35/IV 11000 Belgrade http://www.ai.ac.rs [email protected] Tel. +381 11 2637-191 EDITOR IN CHIEF Miomir Korać Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade EDITORS Snežana Golubović Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade Nemanja Mrđić Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade GRAPHIC DESIGN Nemanja Mrđić PRINTED BY DigitalArt Beograd PRINTED IN 500 copies ISBN 979-86-6439-039-2 4 CONGRESS COMMITTEES Scientific committee Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology (director) Snežana Golubović, Institute of Archaeology Miroslav Vujović, Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Archaeology Stefan Pop-Lazić, Institute of Archaeology Gordana Jeremić, Institute of Archaeology Nemanja Mrđić, Institute of Archaeology International Advisory Committee David Breeze, Durham University, Historic Scotland Rebecca Jones, Historic Environment Scotland Andreas Thiel, Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart, Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, Esslingen Nigel Mills, Heritage Consultant, Interpretation, Strategic Planning, Sustainable Development Sebastian Sommer, Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Lydmil Vagalinski, National Archaeological Institute with Museum – Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Mirjana Sanader, Odsjek za arheologiju Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Organization committee Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology (director) Snežana Golubović, Institute of Archaeology -

The Landscape and Biodiversity Gorj - Strengths in the Development of Rural Tourism

Annals of the „Constantin Brancusi” University of Targu Jiu, Engineering Series , No. 2/2016 THE LANDSCAPE AND BIODIVERSITY GORJ - STRENGTHS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF RURAL TOURISM Roxana-Gabriela Popa, University “Constantin Brâncuşi”, Tg-Jiu, ROMANIA Irina-Ramona Pecingină, University “Constantin Brâncuşi”, Tg-Jiu, ROMANIA ABSTRACT:The paper presents the context in which topography and biodiversity Gorj county represent strengths in development of rural tourism / ecotourism. The area is characterized by the diversity of landforms, mountains , hills, plateaus , plains, meadows , rivers , natural and artificial lakes, that can be capitalized and constitute targets attraction. KEY WORDS: landscape, biodiversity, tourism, rural 1. PLACING THE ENVIRONMENT Gorj County has a significant tourism GORJ COUNTY potential, thanks to a diversified natural environment , represented by the uniform Gorj County is located in the south - west of distribution of relief items , dense river Romania, in Oltenia northwest. It borders the network , balanced and valuable resources for counties of Caras Severin , Dolj, Hunedoara, climate and landscape area economy. Mehedinţi and Vâlcea. Gorj county occupies an area of 5602 km2, which represents 2.3% 2. GORJ COUNTY RELIEF of the country. Overlap almost entirely of the middle basin of the Jiu , which crosses the The relief area includes mountain ranges, hills county from north to south. From the and foothill extended a hilly area in the administrative point of view , Gorj county is southern half of the county. Morphologically, divided into nine cities, including 2 cities Gorj county has stepped descending from (Targu- Jiu- county resident and Motru), cities north to south. Bumbeşti -Jiu, Novaci, Rovinari, Targu Mountains are grouped in the north of the Cărbuneşti, Tismana, Turceni, Ticleni, 61 county and occupies about 29 % of the common and 411 village (Figure 1.) county. -

Situație Cu Obiectivele Autorizate Din Punct De Vedere Al

MINISTERUL AFACERILOR INTERNE Exemplar nr. 1 DEPARTAMENTUL PENTRU SITUAŢII DE URGENŢĂ Nr. 40212 din INSPECTORATUL GENERAL PENTRU SITUAŢII DE URGENŢĂ Târgu Jiu INSPECTORATUL PENTRU SITUAŢII DE URGENŢĂ “LT.COL. DUMITRU PETRESCU” AL JUDEŢULUI GORJ OBIECTIVE AUTORIZATE DIN PUNCT DE VEDERE AL SECURITĂŢII LA INCENDIU PE ANUL 2009 NR. NR. AUTORIZAŢIE DENUMIREA ADRESA/DENUMIREA CONSTRUCŢIEI CRT DE SECURITATE TITULARULUI PENTRU CARE A FOST EMISĂ LA INCENDIU AUTORIZAŢIEI AUTORIZAŢIA DE SECURITATE LA INCENDIU 1 898001 SC. DUDU SRL Cabana turistica montana 04.02.2009. 0251/471021 NOVACI, RINCA, STR. I ROIBU, NR.23 2 898002 SC. RODNA SRL Spatiu comercial P+1 04.02.2009. 0253/321607 TG-JIU, ALEEA PIETII, NR. 1. 3 898003 SC. TDG VILCEA Spatiu de depozitare 04.02.2009. SRL TG-JIU, STR. E. TEODOROIU, NR. 516 0722/207977 4 898004 SC. DUDU SRL Cabana turistica montana 05.02.2009. 0251/471021 NOVACI, RINCA, STR. I ROIBU, NR.23 5 898005 SC. EDILTERA SRL Pensiune turistica 15.02.2009 0353/806421 TG-JIU, STR. GRIVITEI, NR.26. 6 898006 SC. COLGORJ SRL Motel 20.02.2009. 0724/459974 TG-JIU, STR.JIULUI, NR. 3. 7 898007 SC. VEOLARIS SRL Pensiune turistica 20.02.2009. 0723/519369 RINCA, STR. I ROIBU, NR. 74 8 898008 SC. NAZIRA SRL Sp. Comercial 02.04.2009. 0253/223966 TG-JIU, STR.BARAJELOR. 9 898009 SC. ALEX Pensiune turistica 02.04.2009 &ANDREEA RINCA, NR 116 10 898010 SC. EVRIKASA Pensiune Agroturistica 09.04.2009. 0740/275554 COM. POLOVRAGI 11 898011 ZERNOVEANU Pensiune turistica 24.04.2009. LAVINIA COM. BAIA DE FIER, SAT. -

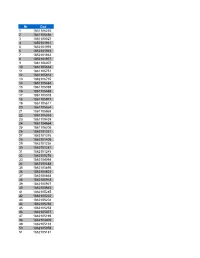

Retea Scolara

Nr Cod 1 1831106235 2 1841105456 3 1861100027 4 1852101941 5 1852101959 6 1852101923 7 1852101932 8 1852101977 9 1881106007 10 1861105638 11 1861105751 12 1861105914 13 1882106735 14 1861105484 15 1861105398 16 1861105588 17 1861100018 18 1861105977 19 1861105611 20 1861105864 21 1861105968 22 1861105353 23 1861105439 24 1861104664 25 1861106205 26 1862101331 27 1862101376 28 1862101408 29 1862101236 30 1862101281 31 1862101245 32 1862105276 33 1862104094 34 1862100488 35 1862100895 36 1862100823 37 1862100868 38 1862100918 39 1862100927 40 1862100945 41 1862105285 42 1862105222 43 1862105204 44 1862105294 45 1862105258 46 1862105077 47 1862105199 48 1862104809 49 1862105163 50 1862105059 51 1862105181 52 1861104596 53 1861105543 54 1862104777 55 1862102938 56 1862102567 57 1862103586 58 1862102635 59 1862106431 60 1862102047 61 1862105136 62 1862103134 63 1862100497 64 1862104058 65 1862102671 66 1862103835 67 1862104203 68 1862100606 69 1862103826 70 1862102282 71 1862103785 72 1862100651 73 1862103966 74 1862100122 75 1862102083 76 1862100434 77 1862101679 78 1862104239 79 1862101661 80 1862103283 81 1862103844 82 1862100981 83 1862103238 84 1862103912 85 1862103618 86 1862100407 87 1862100303 88 1862102133 89 1862100416 90 1862101091 91 1862103179 92 1862103532 93 1862103627 94 1862103609 95 1862103306 96 1862104379 97 1862102531 98 1862103107 99 1862104402 100 1862104483 101 1862101584 102 1862101566 103 1862102617 104 1862105095 105 1862104013 106 1862104949 107 1862103342 108 1862106485 109 1862102196 110 1862103021 111 1862104456 -

The Catalogue of the Freshwater Crayfish (Crustacea: Decapoda: Astacidae) from Romania Preserved in “Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History of Bucharest

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © Décembre Vol. LIII pp. 115–123 «Grigore Antipa» 2010 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-010-0008-5 THE CATALOGUE OF THE FRESHWATER CRAYFISH (CRUSTACEA: DECAPODA: ASTACIDAE) FROM ROMANIA PRESERVED IN “GRIGORE ANTIPA” NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY OF BUCHAREST IORGU PETRESCU, ANA-MARIA PETRESCU Abstract. The largest collection of freshwater crayfish of Romania is preserved in “Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History of Bucharest. The collection consists of 426 specimens of Astacus astacus, A. leptodactylus and Austropotamobius torrentium. Résumé. La plus grande collection d’écrevisses de Roumanie se trouve au Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle «Grigore Antipa» de Bucarest. Elle comprend 426 exemplaires appartenant à deux genres et trois espèces, Astacus astacus, A. leptodactylus et Austropotamobius torrentium. Key words: Astacidae, Romania, museum collection, catalogue. INTRODUCTION The first paper dealing with the freshwater crayfish of Romania is that of Cosmovici, published in 1901 (Bãcescu, 1967) in which it is about the freshwater crayfish from the surroundings of Iaºi. The second one, much complex, is that of Scriban (1908), who reports Austropotamobius torrentium for the first time, from Racovãþ, Bahna basin (Mehedinþi county). Also Scriban made the first comment on the morphology and distribution of the species Astacus astacus, A. leptodactylus and Austropotamobius torrentium, mentioning their distinctive features. Also, he published the first drawings of these species (cephalothorax). Entz (1912) dedicated a large study to the crayfish of Hungary, where data on the crayfish of Transylvania are included. Probably it is the amplest paper dedicated to the crayfish of the Romanian fauna from the beginning of the last century, with numerous data on the outer morphology, distinctive features between species, with more detailed figures and with the very first morphometric measures, and also with much detailed data on the distribution in Transylvania. -

P. Serafimov ETYMOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of THRACIAN TOPONYMS and HYDRONYMS

134 P. Serafimov ETYMOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THRACIAN TOPONYMS AND HYDRONYMS Abstract This paper offers an etymological analysis of more than 60 Thracian toponyms, hydronyms and oronyms. It presents the evidence that the Slavs were the indigenous population in the region, in agreement to the testimony of Simokatta, who equated Thracians (called Getae) with the Old Slavs: «Sclavos sive Getas hoc enim nomine antiquitus appellati sunt” – “Slavs or Getae, because this is the way they were called in the antiquity”. Introduction The toponyms, hydronyms and oronyms can provide very valuable information about the inhabitants of certain lands, because every ethnic group has their own names for moun- tain, valley, lake, and village more or less different from these of the other people. Slavic Bela Gora (White mountain) corresponds to German Weiss Berg, the Greek Λέύκος Oρος and Latin Albus Mons. Judging by these differences and peculiarities we can determine the ethnic affiliation of people who lived a long time ago in a certain geographical area. In this paper the attention is given to the Old Thracian lands: from the Carpathian Mountains to Asia Minor and from Black Sea till Dardania (Serbia). But I have to clarify that these regions do not represent the totality of the Thracian domain, in reality it continued to the Hercynian forest (Schwarzwald in Germany), Map 1, where according to Strabo the country of the Getae began [1], VII-2-III-1. Facts and discussion The terms for different types of settlements in the Thracian lands were: DABA (DAVA), PARA (PHARA), BRIA, DIZA, MIDNE, OSS (VIS), and DAMA. -

Gorj, Săptămâna 13 Mai – 19 Mai 2019

ÎNTRERUPERI PROGRAMATE – JUDEŢUL GORJ, SĂPTĂMÂNA 13 MAI – 19 MAI 2019 Distribuţie Oltenia execută lucrări programate în reţelele electrice pentru creşterea gradului de siguranţă şi continuitate în alimentarea cu energie electrică a consumatorilor, precum şi a îmbunătăţirii parametrilor de calitate ai energiei electrice distribuite. Distribuţie Oltenia anunţă întreruperea furnizării energiei electrice la consumatorii casnici şi agenţii economici, astfel: Interval orar Data Localitatea Zona de întrerupere de întrerupere 09:00 - 15:00 Stejari PTA Hurezanii de Stejari nr. 2 - sat Hurezanii de Stejari 08:00 - 15:00 Stoina PTA Stoina nr. 1 - Sat Stoina - parțial 13.05 09:00 - 15:00 Turburea PTA Sipot - sat Sipot, PTA Turburea de Sus - sat Turburea de Sus 09:00 - 15:00 Țînțăreni PTA Florești nr. 5 - sat Florești - parțial 09:00 - 15:00 Telești PTA Telești nr. 2 - sat Telești - parțial 14.05 08:00 - 15:00 Tismana PTA Vînăta - sat Vînăta PTAB 36, PTA 260, PTA 52, Cartier Tișmana, stăzile: Merilor, Microcolonie, Călăraș, Meteor și Aleea Călăraș, PTA 09:00 - 17:00 Târgu Jiu 230, străzile: Barajelor și Jiului 09:00 - 15:00 Alimpești PTA Alimpești nr 1 - sat Alimpești - parțial 15.05 09:00 - 15:00 Baia de Fier PTA Baia de Fier nr. 1 - sat Baia de Fier - parțial 09:00 - 15:00 Țînțăreni PTA Florești nr. 6 - sat Florești - parțial 16.05 PTAB 36, PTA 260, PTA 52, Cartier Tișmana, stăzile: Merilor, Microcolonie, Călăraș, Meteor și Aleea Călăraș, PTA 09:00 - 17:00 Târgu Jiu 230, străzile: Barajelor și Jiului 09:00 - 15:00 Mătăsari PTA Brădet nr. 2 - sat Brădet 17.05 09:00 - 15:00 Stănești PTA Polata - sat Polata 09:00 - 15:00 Stănești PTAB Obreja - sat Obreja, PTAB Călești - sat Călești, PTA Măzăroi - sat Măzăroi, PTA Crețu (terț) Lucrările pot fi reprogramate în situaţia în care condiţiile meteo sunt nefavorabile. -

Elements of Specificity Regarding the Technical State of Historical Constructions with Defense Role

BULETINUL INSTITUTULUI POLITEHNIC DIN IAŞI Publicat de Universitatea Tehnică „Gheorghe Asachi” din Iaşi Volumul 65 (69), Numărul 2, 2019 Secţia CONSTRUCŢII. ARHITECTURĂ ELEMENTS OF SPECIFICITY REGARDING THE TECHNICAL STATE OF HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTIONS WITH DEFENSE ROLE BY ANDREI-VICTOR ANDREI* and LIVIA INGRID DIACONU Technical University “Gh. Asachi” of Iasi, Faculty of Civil Engineering and Building Services, Received: May 17, 2019 Accepted for publication: June 27, 2019 Abstract. Historical defensive construction is a term that defines a construction designed to provide protection, capable of serving military action and having implications for local, national and universal history, culture and civilization. The construction of the fortifications, their type and strategic positioning required a special architecture, special siege weapons, the choice and adoption of a strategy and tactics appropriate for conquest or defense. For a proper assessment of the technical state of a historic building with a defense role, particular attention should be paid to specific architectural elements such as: defense walls built of earth or stone, defense towers that can have shapes, ramparts, firing holes, guard roads, water supply, cellars, the reserve of building materials, made up for the reconstruction of the enemy's destruction, not least, these elements with a strategic, technical and tactical role are added to the living quarters, the care of the wounded, the preparation of the food and the rest. Keywords: historical defensive construction; fortifications; technical state; degradation, stone. *Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] 102 Andrei-Victor Andrei and Livia Ingrid Diaconu 1. Introduction In particular, in the case of historical constructions, knowledge and assessment of constructive features is an important source of information for establishing the course of the rehabilitation. -

Epigraficeiscylptyral1

MONVMENTELE EPIGRAFICEISCYLPTYRAL1 ALE -AryzEviNT NATIONAL DE ANTICHITATI DIN BVCVRETI PVBLICATE SVI3 AVSPICIILE ACADEMIEI ROMANE DE GR.G. TOCILESCV Membru al Academiei Romano, al Institutelor archeologice din Roma si Viena, al Sccietiltilor archeologice din Paris, Orleans, Bruxelles, Roma, Atena, Odesa gi Moscova, al Societatii geografice, numismaticei istorice din Bucuresti, al Societatii istorice din Moscova, al Societatii de etnograflesiantropologie din Paris, etc., Vice-preseclinte al Ateneului Roman, Prof..la Universitatea din Bucuresti, Director al Muzeului national de antichitati, etc. 1 PARTEA II COLECTIVNEA SCVLPTVRALA. A MVZEVLVI PA.N.A. IN ANVL 1881. IBUCURETI NOIJA TIPOGRAFIE PROFESIONALA DIM. C. IONESCIT io.-STRADA SELARE. Jo. r 1908 a ..NicoLAe BALCESCU" PARTEA II MONVMENTELE SCVLPTVRALI I RELIEFURI ANTICE N.. 1 Capul in relief al unui rege al Assyriei, (pate Aur- nasir-pal), sail al until resbornic assyrian. Relieful oblu neinfatiseza,intr'omarime superiors Desoriptinnea. naturel, capul until rege al Assyriel, pate al lul Aur- nasir- pal, sail al unui resboinic assyrian. Perul capulul este acoperit pang la frunte§icefa de o legatura fa'cuta in chip de tichie §i fixata cu o curea latti pe dupa, urechY. Barba cea lungs, ca ipletele lasate pe spate, sunt frisate in carliontl. Monumentul provine din ruinele anticuluY ora§ Niniveh,Proveninta unde a fost gasit de d. Cocio Cohen impreuna cu fragmentul din inscriptiunea analelor lul A§ur-nasir-pal, regale Assyriel, publicat inacesta opera sub nr. 97 (pag. 479)§i avand aceia§1 proveninta 1). Faptul acesta al unel proveninteco- 1) Proveninta dela Niniveh a ambelor monumente se atesti prin raportul nr. 13 din 12 Maiti 1869 adresat Ministerukil instructiunki publice de clitre con- servatorul Musgulul de AntichitAtI. -

Unitati Afiliate GORJ 25.03.2021

LISTA UNITATILOR CARE PREGATESC SI SERVESC/ LIVREAZA MESE CALDE SI CARE ACCEPTA TICHETE SOCIALE PENTRU MESE CALDE JUDETUL GORJ Nr. crt. Localitate Denumire unitate partenera Adresa unitatii partenere/punctului de lucru care ofera mese calde Nr. telefon 1 ALBENI RESTAURANT & CATERING LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 2 ALBENI ARINDIRAZ SRL -RESTAURANT ALBENI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 3 ALBENI FAIGRASSO COM SRL livrare ALBENI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0733422422 4 ALIMPESTI RESTAURANT& CATERING ALIMPESTI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 5 ALIMPESTI 3 AXE RESTAURANT ALIMPESTI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0722684062 6 ALIMPESTI 3 AXE RESTAURANT CIUPERCENI DE OLTET LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 722684062 7 ALIMPESTI ARINDIRAZ SRL -RESTAURANT ALIMPESTI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 8 ANINOASA RESTAURANT & CATERING ANINOASA LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 9 ANINOASA DKD INFINITI GROUP SRL CATERING ANINOASA LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0765885500 10 ANINOASA FAIGRASSO COM SRL livrare ANINOASA LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0733422422 11 ARCANI PENSIUNEA LUMINITA TRAVEL RESTAURANT ARCANI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0765275015 12 ARCANI PENSIUNEA LA MOARA CATERING ARCANI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0747377377/0726696633 PENSIUNEA LUMINITA TRAVEL RESTAURANT 13 ARCANI SANATESTI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0765275015 14 ARCANI RESTAURANT LA MARCEL STR. PRINCIPALA NR.328, 217025 0720245414 15 BAIA DE FIER PENSIUNE TURISTICA SUPER PANORAMIC ZONA RANCA, CORNESUL MARE 0732281990/0733998811 16 BAIA DE FIER RESTAURANT HOTEL ONIX STATIUNEA RANCA STATIUNEA RANCA, CORNESUL MARE 0744614743 17 BAIA DE FIER TOBO PENSIUNE -

Cercetările Arheologice in Dava De La Răcătău-Tamasidava, Intre Anii 19.92-1996 De Viorel Căpitanu

Cercetările arheologice in Dava de la Răcătău-Tamasidava, intre anii 19.92-1996 de Viorel Căpitanu În anul 1992 au fost reluate cercetările arheologice în staţiunea de la Răcătău, pe acropolă, trasându-se o nouă secţiune, S XXXV, cu lungimea de 26 m, şi lăţimea de 6 m , amplasată în partea de E faţă de S 1/1968, într-o zonă intens locuită în secolele 1 î.d.H. - 1 d.H. Începând de la -0,30 m şi-au făcut apariţia locuintele de suprafaţă, în carou riie 1 ,3,7,8,9 şi 10, cu care ocazie au fost identificate un număr de 14 1ocuinţe din care 12 aparţin civilizaţiei geto-dacice şi 2 epocii bronzului, cultura Monteoru. Mai menţionăm o locuinţă adâncită, care se datează în secolul li î.de.H. Din punct de vedere stratigrafic situaţia este identică cu cea întâlnită în celelalte sectiuni. Astfel primul nivel de locuire aparţine epocii bronzului, cultura Monteoru cu cele două faze, lc2 şi lc3. Al doilea nivel de locuire aparţine civilizaţiei geto-dacice şi aparţine secolelor IV-III î.de H-şi până la începutul sec. li d.H. Şi în această sectiune au fost surprinse un mare număr de gropi, începând de la - 0,60 m, cu adâncimile cuprinse între 1,80 - 2, 00 m şi chiar până la 3 m. Stratul de cultură dacic este foarte bogat în material arheologic cu o mare cantitate de ceramică geto - dacică şi de import, lucrată cu mâna şi la roată, din pastă fină, dar şi de aspect poros, simplă sau ornamentată cu decor alveolar, incizat sau lustruit la vasele borcan sau ceştile dacice, cu pe cu două torţi, fructiere, urcioare, chiupuri, vase de provizii etc. -

1907 in Judeţul Gorj 67

1907 IN JUDEŢUL GORJ RADESCU NICOLINA .Istoria socială a României la începutul secolului al XX lea înscrie una din cele mai puternice lupte pe care le-a dus de-a lungul veacurilor ţărănimea : marea răscoală din anul 1907. Ridiearea la luptă a ţărănimii in primăvara anului 1907 a reliefat cu o deosebită forţă, curajul, cutezanţa, spiritul de sacrificiu al „truditorilor ogoarelor" pentru libertate şi dreptate socială, hotărîrea lor de a înlătura exploatarea, nă zuinţa de a-şi făuri o viaţă demnă. Prin proporţiile şi inten sitateâ ei, răscoala ţărănimii din 1907 a scos în evidenţă n~cesitatea imperioasă a rezolvării problemei agrare. Ea a dezvăluit marile energii revoluţionare ale ţărănimii, repre zentînd „una din paginile glorioase ale luptei sociale a po porului român".1 Răscoala din 1907 nu a apărut spontan, nu a fost o în• tîmplare ci produsul contradicţiilor societăţii româneşti în epocă, expresia setei de libertate a ţărănimii. A fost conse cinţa unui regim ce se cerea înlăturat odată pentru totdea una. Secret.arul general al partidului tovarăşul Nicolae Ceauşeşcu, vorbind despre însemnătatea memorabilului e· veniment din. 1907 Sublinia : „Unul din momentele istorice de neuitat, care va vorbi peste veacuri de uriaşa energie revoluţionară a ţărănimii este anul 1907, anul ce a făcut s~ se cutremure clasele exploatatoare din România".2 Marele nostru istoric Nicolae Iorga, la debutul său în Parlament, în toamna anului 1907, vorbind despre ridicarea la luptă a ţărănimii spunea: „„.ţărănimea aceasta, dacă s-ar fi resemnat a trăi în