Housing Strategies for Growth in Neepawa, Manitoba: a Planning Perspective on Preparing for New Immigrants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Plum Coulee, Rural Municipality of Rhineland and Town

As of 27 Sep 2021, this is the most current version available. It is current Le texte figurant ci-dessous constitue la codification la plus récente en for the period set out in the footer below. It is the first version and has not date du 27 sept. 2021. Son contenu était à jour pendant la période been amended. indiquée en bas de page. Il s'agit de la première version; elle n’a fait l'objet d'aucune modification. THE MUNICIPAL AMALGAMATIONS ACT LOI SUR LA FUSION DES MUNICIPALITÉS (C.C.S.M. c. M235) (c. M235 de la C.P.L.M.) Town of Plum Coulee, Rural Municipality of Règlement sur la fusion de la ville de Plum Rhineland and Town of Gretna Amalgamation Coulee, de la municipalité rurale de Regulation Rhineland et de la ville de Gretna Regulation 135/2014 Règlement 135/20014 Registered May 2, 2014 Date d'enregistrement : le 2 mai 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE DES MATIÈRES Section Article 1 Definitions 1 Définitions 2 New municipality established 2 Constitution d'une nouvelle municipalité 3 Boundaries 3 Limites 4 Status of new municipality 4 Statut de la nouvelle municipalité 5 Composition of council 5 Composition du conseil 6 Voters list 6 Liste électorale 7 Appointment of senior election official 7 Nomination du fonctionnaire électoral 8 Election expenses and contributions principal by-law 8 Règlement municipal sur les dépenses et 9 Application les contributions électorales 10 Term of office for members of first 9 Application council 10 Mandat des membres du premier conseil 11 Extension of term of office of old 11 Prolongation du mandat des -

Order No. 43/20 MUNICIPALITY of RHINELAND AMALGAMATION OF

Order No. 43/20 MUNICIPALITY OF RHINELAND AMALGAMATION OF THE RHINELAND, PLUM COULEE AND GRETNA WATER AND WASTEWATER UTILITIES REVISED WATER AND WASTEWATER RATES March 27, 2020 BEFORE: Shawn McCutcheon, Panel Chair Irene A. Hamilton, Q.C., Panel Member Room 400 – 330 Portage Avenue 330, avenue Portage, pièce 400 Winnipeg, MB R3C 0C4 Winnipeg (Manitoba) Canada R3C 0C4 www.pubmanitoba.ca www.pubmanitoba.ca Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ............................................................................................ 4 2.0 Background ......................................................................................................... 6 Water Supply/Distribution ..................................................................................... 6 Wastewater Collection and Treatment .................................................................. 6 3.0 Board Methodology ............................................................................................. 7 Review Process .................................................................................................... 7 Interim ex parte Approval ...................................................................................... 7 Contingency Allowance and Utility Reserves ........................................................ 7 Working Capital .................................................................................................... 8 Operating Deficits ................................................................................................ -

Neepawa, Manitoba

Neepawa, Manitoba Developed By Welcome to Sunrise Manor in the Heart of Neepawa Reserve your unit today! The overall purpose of the corporation is to support and Maintenance Free enhance independent and healthy living for seniors in the Town Affordable Living of Neepawa, Manitoba. Sunrise Manor will be located on the Quiet and Peaceful CN Land, for active adults which is on the Yellowhead Highway 16 at the intersection with Highway 5. This three-story development is perfect for active older adults seeking a simplified lifestyle — one that is engaging, social, and free from daily responsibilities like housekeeping and home maintenance. The building consists of one and two-bedroom apartment units. All Developed, owned and operated by Stone Cliff Builders Inc. apartments are spacious and fully equipped with a private balcony. If you or someone you know are seeking secure and affordable July 2018 retirement living in a supportive and home-like environment, plan to make Sunrise Manor your new home. Contents subject to change without notice. Ready to make Sunrise Features & Amenities Manor your new home? The Building • Private dining room for family • Beautifully designed 3-story building occasions with brick and acrylic stucco • Proximity card “key” system at main Accessible • Covered canopy at front entrances entrance for ease of access to the Design of the building and living unites building capable of accomodating the special • Quiet hydraulic elevator • On-site staff for building administration mobility needs of seniors. • Professionally landscaped grounds and maintenance • Parking for residents and guests • Smoke detectors system throughout suites and building with central Suites monitoring • Spacious 1 and 2-bedroom apartments with private balconies Added Conveniences / Activities A | One Bedroom Unit • Modern galley style kitchen with Additional Options Available Social and recreational activities help approx. -

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the Period 2002 to 2012

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the period 2002 to 2012 The following list identifies the RHAs and RHA Districts in Manitoba between the period 2002 and 2012. The 11 RHAs are listed using major headings with numbers and include the MCHP - Manitoba Health codes that identify them. RHA Districts are listed under the RHA heading and include the Municipal codes that identify them. Changes / modifications to these definitions and the use of postal codes in definitions are noted where relevant. 1. CENTRAL (A - 40) Note: In the fall of 2002, Central changed their districts, going from 8 to 9 districts. The changes are noted below, beside the appropriate district area. Seven Regions (A1S) (* 2002 changed code from A8 to A1S *) '063' - Lakeview RM '166' - Westbourne RM '167' - Gladstone Town '206' - Alonsa RM 'A18' - Sandy Bay FN Cartier/SFX (A1C) (* 2002 changed name from MacDonald/Cartier, and code from A4 to A1C *) '021' - Cartier RM '321' - Headingley RM '127' - St. Francois Xavier RM Portage (A1P) (* 2002 changed code from A7 to A1P *) '090' - Macgregor Village '089' - North Norfolk RM (* 2002 added area from Seven Regions district *) '098' - Portage La Prairie RM '099' - Portage La Prairie City 'A33' - Dakota Tipi FN 'A05' - Dakota Plains FN 'A04' - Long Plain FN Carman (A2C) (* 2002 changed code from A2 to A2C *) '034' - Carman Town '033' - Dufferin RM '053' - Grey RM '112' - Roland RM '195' - St. Claude Village '158' - Thompson RM 1 Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area -

Endowment Funds 1921-2020 the Winnipeg Foundation September 30, 2020 (Pages 12-43 from Highlights from the Winnipeg Foundation’S 2020 Year)

Endowment Funds 1921-2020 The Winnipeg Foundation September 30, 2020 (pages 12-43 from Highlights from The Winnipeg Foundation’s 2020 year) Note: If you’d like to search this document for a specific fund, please follow these instructions: 1. Press Ctrl+F OR click on the magnifying glass icon (). 2. Enter all or a portion of the fund name. 3. Click Next. ENDOWMENT FUNDS 1921 - 2020 Celebrating the generous donors who give through The Winnipeg Foundation As we start our centennial year we want to sincerely thank and acknowledge the decades of donors from all walks of life who have invested in our community through The Winnipeg Foundation. It is only because of their foresight, commitment, and love of community that we can pursue our vision of “a Winnipeg where community life flourishes for all.” The pages ahead contain a list of endowment funds created at The Winnipeg Foundation since we began back in 1921. The list is organized alphabetically, with some sub-fund listings combined with the main funds they are connected to. We’ve made every effort to ensure the list is accurate and complete as of fiscal year-end 2020 (Sept. 30, 2020). Please advise The Foundation of any errors or omissions. Thank you to all our donors who generously support our community by creating endowed funds, supporting these funds through gifts, and to those who have remembered The Foundation in their estate plans. For Good. Forever. Mr. W.F. Alloway - Founder’s First Gift Maurice Louis Achet Fund The Widow’s Mite Robert and Agnes Ackland Memorial Fund Mr. -

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload Updated December 17, 2019 Serviced Out Of City Prov Routing City Carrier Name ADAM LAKE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ALEXANDER MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ALONSA MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ALTAMONT MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ALTONA MB WINNIPEG, MB Direct Service Point AMARANTH MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ANGUSVILLE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ANOLA MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARBORG MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARDEN MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARGYLE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARNAUD MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARNES MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARROW RIVER MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ASHERN MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ATIKAMEG LAKE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point AUBIGNY MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point AUSTIN MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BADEN MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BADGER MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BAGOT MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BAKERS NARROWS MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BALDUR MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BALMORAL MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BARROWS MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BASSWOOD MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BEACONIA MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BEAUSEJOUR MB WINNIPEG, MB Direct Service Point BELAIR MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BELMONT MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BENITO MB YORKTON, SK Interline Point BERESFORD MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BERESFORD LAKE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BERNIC LAKE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BETHANY MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BETULA MB WINNIPEG, -

Pdfs GST-HST Municipal Rebates 2019 E Not Finished.Xlsx

GST/HST Incremental Federal Rebate for Municipalities Report - January 1 to December 31, 2019 Manitoba PAYMENT LEGAL NAME CITY NAME FSA AMOUNT 2625360 MANITOBA ASSOCIATION INC. NEEPAWA R0J $2,993.73 285 PEMBINA INC WINNIPEG R2K $10,624.47 4508841 MANITOBA ASSOCIATION INC WINNIPEG R2K $517.02 474 HARGRAVE CORPORATION WINNIPEG R3A $2,504.76 6869166 MANITOBA LTD. SANFORD R0G $7,370.38 ACADEMY ROAD BUSINESS IMPROVMENT ZONE WINNIPEG R3N $1,389.15 AGASSIZ WEED CONTROL DISTRICT BEAUSEJOUR R0E $549.30 ALTONA RURAL WATER SERVICES CO-OP LTD ALTONA R0G $1,860.62 ARBORG BI-FROST PARKS & RECREATION COMMISSION ARBORG R0C $5,326.89 ARGYLE-LORNE-SOMERSET WEED CONTROL DISTRICT BALDUR R0K $553.10 ARLINGTONHAUS INC. WINNIPEG R2K $11,254.49 ARTEMIS HOUSING CO-OP LTD WINNIPEG R3A $2,784.09 ASTRA NON-PROFIT HOUSING CORPORATION WINNIPEG R2K $2,993.66 AUTUMN HOUSE INC. WINNIPEG R3E $3,532.89 B&G UTILITIES LTD BRANDON R7B $3,643.38 BAPTIST MISSION APARTMENTS INC. WINNIPEG R3E $2,224.34 BARROWS COMMUNITY COUNCIL BARROWS R0L $3,837.41 BEAUSEJOUR BROKENHEAD DEVELOPMENT CORP BEAUSEJOUR R0E $3,583.19 BETHANIAHAUS INC. WINNIPEG R2K $17,881.45 BIBLIOTHÉQUE MONTCALM LIBRARY SAINT-JEAN-BAPTISTE R0G $180.01 BIBLIOTHÉQUE REGIONALE JOLYS REGIONAL LIBRARY SAINT-PIERRE-JOLYS R0A $267.88 BIBLIOTHÉQUE TACHÉ LIBRARY LORETTE R0A $851.71 BISSETT COMMUNITY COUNCIL BISSETT R0E $2,919.53 BLUMENFELD HOCHFELD WATER CO-OP LTD WINKLER R6W $770.13 BLUMENORT SENIOR CITIZENS HOUSING INC. STEINBACH R5G $515.67 BOISSEVAIN - MORTON LIBRARY AND ARCHVIES BOISSEVAIN R0K $784.80 BOISSEVAIN AND MORTON -

The Community Living Funding Crisis in Westman and Parkland a REPORT on 15 AGENCIES

The Community Living Funding Crisis in Westman and Parkland A REPORT ON 15 AGENCIES An analysis of systemic problems and recommendations to address these concerns April 2014 Dr. Megan McKenzie, Conflict Specialist Table of Contents Contents Executive Summary __________________________________________________________ 1 Summary of Recommendations _________________________________________________ 3 The Funding Crisis ___________________________________________________________ 6 ACL Swan River ____________________________________________________________ 31 ACL Virden ________________________________________________________________ 33 Brandon Community Options __________________________________________________ 36 Community Respite Services (Brandon) __________________________________________ 39 COR Enterprises Inc. (Brandon) ________________________________________________ 42 Frontier Trading Company Inc. (Minnedosa) ______________________________________ 45 Grandview Gateways Inc. _____________________________________________________ 47 Parkland Residential and Vocational Services Inc. (Dauphin) _________________________ 51 Prairie Partners (Boissevain) __________________________________________________ 54 ROSE Inc. (Ste. Rose du Lac) _________________________________________________ 56 Rolling Dale Enterprises Inc.(Rivers) ____________________________________________ 59 Southwest Community Options (Ninette) _________________________________________ 61 Touchwood Park (Neepawa) ___________________________________________________ 65 Westman -

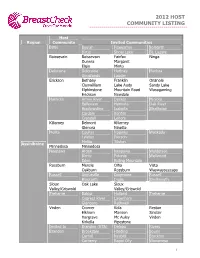

2012 Host Community Listing

2012 HOST COMMUNITY LISTING Host Region Community Invited Communities Birtle Beulah Foxwarren Solsgirth Birtle Shoal Lake St. Lazare Boissevain Boissevain Fairfax Ninga Dunrea Margaret Elgin Minto Deloraine Deloraine Hartney Medora Goodlands Lauder Erickson Bethany Franklin Onanole Clanwilliam Lake Audy Sandy Lake Elphinstone Mountain Road Wasagaming Erickson Newdale Hamiota Arrow River Decker Miniota Belleview Hamiota Oak River Bradwardine Isabella Strathclair Cardale Kenton Crandall Lenore Killarney Belmont Killarney Glenora Ninette Melita Coulter Napinka Waskada Lyleton Pierson Melita Tilston Assiniboine Minnedosa Minnedosa Neepawa Arden Neepawa Waldersee Birnie Polonia Wellwood Eden Riding Mountain Rossburn Menzie Olha Vista Oakburn Rossburn Waywayseecapo Russell Angusville Dropmore Russell Binscarth Inglis Shellmouth Sioux Oak Lake Sioux Valley/Griswold Valley/Griswold Treherne Baldur Holland Treherne Cypress River Lavenham Glenboro Rathwell Virden Cromer Kola Reston Elkhorn Manson Sinclair Hargrave Mc Auley Virden Kirkella Pipestone Invited to Brandon (R7A) Deleau Rivers Brandon Brookdale Harding Souris Carroll Nesbitt Stockton Carberry Rapid City Wawanesa 1 2012 HOST COMMUNITY LISTING Host Region Community Invited Communities Invited to Cartwright Holmfield Mather Assiniboine Crystal City (cont.) Invited to Glenella Kelwood McCreary Churchill Churchill Cross Lake Cross Lake Gillam Gillam Ilford Shamattawa Leaf Rapids Leaf Rapids South Indian Lake Lynn Lake Brochet Lynn Lake Lac Brochet Tadoule Lake Burntwood Nelson House Nelson -

Guide to Manitoba Memorial Types

GUIDE TO MANITOBA MEMORIAL TYPES War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy GUIDE TO MANITOBA MEMORIAL TYPES he memorials honouring Manitoba’s dead of World War I are a profound historical legacy. They are also a major artistic achievement. This section of the study of Manitoba war memorials explores the Tmost common types of memorials with an eye to formal considerations – design, aesthetics, materials, and craftsmanship. For those who look to these objects primarily as places of memory and remembrance, this additional perspective can bring a completely different level of understanding and appreciation, and even delight. Six major groupings of war memorial types have been identified in Manitoba: Tablets Cairns Obelisks Cenotaphs Statues Architectural Monuments Each of these is reviewed in the following entries, with a handful of typical or exceptional Manitoba examples used to illuminate the key design and material issues and attributes that attend the type. Guide to Manitoba Memorial Types 1 War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy Tablets The apparently simple and elemental form of the tablet, also known as a stele (from the ancient Greek, with stelae as the plural), is the most common form of gravesite memorial. Given its popularity and cultural and historical resonance, its use for war memorials is understandable. The tablet is economical—in form and often in cost—but also elegant. And while the simple planar face is capable of conveying a great deal of inscribed information, the very form itself can be seen as a highly abstracted version of the human body – and thus often has a mysterious attractive quality. -

Winnipeg Western Northern Eastern

Department o f Families – Regio nal So cial Services Bo undaries Churchill Lynn Lake Gillam Leaf Rapids Thompson Mystery Lake Snow Lake Flin Flon Manitoba Winnipeg Bo undaries The Pas Seven Oaks Kelsey River East Grand Rapids Inkster Po int Do uglas St. James Do wnto wn Transco na Assinibo ia River Heights St. Bo niface Minitonas-Bowsman Swan River Assinibo ine Swan Valley So uth West Mountain Mossey River St. Vital Ethelbert Ft. Garry Hillsburg-Roblin-Shell Lakeshore River Grahamdale Dauphin Grandview Gilbert Plains Dauphin Fisher Bifrost-Riverton Alonsa Riding Ste. Rose West Mountain Interlake West Arborg Russell-Binscarth McCreary Victoria Rossburn Beach Armstrong Gimli Coldwell Department o f Families Regio ns Harrison Park Powerview-Pine Falls Glenella-Lansdowne Winnipeg Clanwilliam-Erickson Yellowhead Beach Alexander Dunnottar Rosedale St. Laurent Teulon Winnipeg Lac du Bonnet Prairie View St. Clements St. Rockwood Lac du Bonnet Westlake-Gladstone Andrews Ellice-Archie Minnedosa Neepawa Woodlands Hamiota Oakview Pinawa Selkirk Western Minto-Odanah Stonewall Brokenhead Portage La Beausejour Prairie North Rosser West St. Paul St. François Riverdale Cypress-Langford East St. Paul Elton Portage La Xavier Whitemouth Wallace-Woodworth Prairie North Norfolk Northern Springfield Cartier Winnipeg Virden Carberry Brandon Headingley Whitehead Cornwallis Taché Glenboro-South Cypress Grey Ste. Anne Eastern Pipestone Sifton Norfolk Macdonald Ritchot Reynolds Victoria Ste. Anne Souris-Glenwood Treherne Oakland-Wawanesa Niverville Dufferin Hanover Steinbach Carman Morris Grassland St. La Lorne Pierre-Jolys Broquerie Prairie Lakes Thompson Roland Morris De Salaberry Argyle Melita Brenda-Waskada Rhineland Montcalm Piney Boissevain-Morton Pembina Morden Winkler Two Borders Louise Emerson-Franklin Stuartburn Deloraine-Winchester Killarney-Turtle 0 50 100 200 300 400 Cartwright-Roblin Mountain Stanley Altona Kilometers Edited by Fran Picoto, EMO August 27, 2020. -

Municipal Officials Directory 2021

MANITOBA MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Municipal Officials Directory 21 Last updated: September 23, 2021 Email updates: [email protected] MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Room 317 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3C 0V8 ,DPSOHDVHGWRSUHVHQWWKHXSGDWHGRQOLQHGRZQORDGDEOH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\7KLV IRUPDWSURYLGHVDOOXVHUVZLWKFRQWLQXDOO\XSGDWHGDFFXUDWHDQGUHOLDEOHLQIRUPDWLRQ$FRS\ FDQEHGRZQORDGHGIURPWKH3URYLQFH¶VZHEVLWHDWWKHIROORZLQJDGGUHVV KWWSZZZJRYPEFDLDFRQWDFWXVSXEVPRGSGI 7KH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\FRQWDLQVFRPSUHKHQVLYHFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQIRUDOORI 0DQLWRED¶VPXQLFLSDOLWLHV,WSURYLGHVQDPHVRIDOOFRXQFLOPHPEHUVDQGFKLHI DGPLQLVWUDWLYHRIILFHUVWKHVFKHGXOHRIUHJXODUFRXQFLOPHHWLQJVDQGSRSXODWLRQV,WDOVR SURYLGHVWKHQDPHVDQGFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQRIPXQLFLSDORUJDQL]DWLRQV0DQLWRED([HFXWLYH &RXQFLO0HPEHUVDQG0HPEHUVRIWKH/HJLVODWLYH$VVHPEO\RIILFLDOVRI0DQLWRED0XQLFLSDO 5HODWLRQVDQGRWKHUNH\SURYLQFLDOGHSDUWPHQWV ,HQFRXUDJH\RXWRFRQWDFWSURYLQFLDORIILFLDOVLI\RXKDYHDQ\TXHVWLRQVRUUHTXLUH LQIRUPDWLRQDERXWSURYLQFLDOSURJUDPVDQGVHUYLFHV ,ORRNIRUZDUGWRZRUNLQJLQSDUWQHUVKLSZLWKDOOPXQLFLSDOFRXQFLOVDQGPXQLFLSDO RUJDQL]DWLRQVDVZHZRUNWRJHWKHUWREXLOGVWURQJYLEUDQWDQGSURVSHURXVFRPPXQLWLHV DFURVV0DQLWRED +RQRXUDEOHDerek Johnson 0LQLVWHU TABLE OF CONTENTS MANITOBA EXECUTIVE COUNCIL IN ORDER OF PRECEDENCE ............................. 2 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA – DEPUTY MINISTERS ..................................................... 5 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ............................................................ 7 MUNICIPAL RELATIONS ..............................................................................................