When Privileges Are Demanded As Elite Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

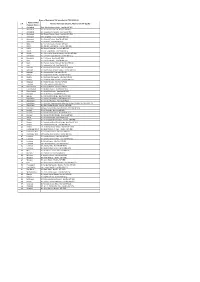

S N. Name of TAC/ Telecom District Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms

Name of Nominated TAC members for TAC (2020-22) Name of TAC/ S N. Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms] Hon’ble MP (LS/RS) Telecom District 1 Allahabad Prof. Rita Bahuguna Joshi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 2 Allahabad Smt. Keshari Devi Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 3 Allahabad Sh. Vinod Kumar Sonkar, Hon’ble MP (LS) 4 Allahabad Sh. Rewati Raman Singh, Hon’ble MP (RS) 5 Azamgarh Smt. Sangeeta Azad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 6 Azamgarh Sh. Akhilesh Yadav, Hon’ble MP (LS) 7 Azamgarh Sh. Rajaram, Hon’ble MP (RS) 8 Ballia Sh. Virendra Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 9 Ballia Sh. Sakaldeep Rajbhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 10 Ballia Sh. Neeraj Shekhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 11 Banda Sh. R.K. Singh Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 12 Banda Sh. Vishambhar Prasad Nishad, Hon’ble MP (RS) 13 Barabanki Sh. Upendra Singh Rawat, Hon’ble MP (LS) 14 Barabanki Sh. P.L. Punia, Hon’ble MP (RS) 15 Basti Sh. Harish Dwivedi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 16 Basti Sh. Praveen Kumar Nishad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 17 Basti Sh. Jagdambika Pal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 18 Behraich Sh. Ram Shiromani Verma, Hon’ble MP (LS) 19 Behraich Sh. Brijbhushan Sharan Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 20 Behraich Sh. Akshaibar Lal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 21 Deoria Sh. Vijay Kumar Dubey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 22 Deoria Sh. Ravindra Kushawaha, Hon’ble MP (LS) 23 Deoria Sh. Ramapati Ram Tripathi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 24 Faizabad Sh. Ritesh Pandey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 25 Faizabad Sh. Lallu Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 26 Farrukhabad Sh. -

Life-Members

Life Members SUPREME COURT BAR ASSOCIATION Name & Address Name & Address 1 Abdul Mashkoor Khan 4 Adhimoolam,Venkataraman Membership no: A-00248 Membership no: A-00456 Res: Apartment No.202, Tower No.4,, SCBA Noida Res: "Prashanth", D-17, G.K. Enclave-I, New Delhi Project Complex, Sector - 99,, Noida 201303 110048 Tel: 09810857589 Tel: 011-26241780,41630065 Res: 328,Khan Medical Complex,Khair Nagar Fax: 41630065 Gate,Meerut,250002 Off: D-17, G.K. Enclave-I, New Delhi 110048 Tel: 0120-2423711 Tel: 011-26241780,41630065 Off: Apartment No.202, Tower No.4,, SCBA Noida Ch: 104,Lawyers Chamber, A.K.Sen Block, Supreme Project Complex, Sector - 99,, Noida 201303 Court of India, New Delhi 110001 Tel: 09810857589 Mobile: 9958922622 Mobile: 09412831926 Email: [email protected] 2 Abhay Kumar 5 Aditya Kumar Membership no: A-00530 Membership no: A-00412 Res: H.No.1/12, III Floor,, Roop Nagar,, Delhi Res: C-180,, Defence Colony, New Delhi 110024 110007 Off: C-13, LGF, Jungpura, New Delhi 110014 Tel: 24330307,24330308 41552772,65056036 Tel: 011-24372882 Tel: 095,Lawyers Chamber, Supreme Court of India, Ch: 104, Lawyers Chamber, Supreme Court of India, Ch: New Delhi 110001 New Delhi 110001 23782257 Mobile: 09810254016,09310254016 Tel: Mobile: 9911260001 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 3 Abhigya 6 Aganpal,Pooja (Mrs.) Membership no: A-00448 Membership no: A-00422 Res: D-228, Nirman Vihar, Vikas Marg, Delhi 110092 Res: 4/401, Aganpal Chowk, Mehrauli, New Delhi Tel: 22432839 110030 Off: 704,Lawyers Chamber, Western Wing, Tis Hazari -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic Vs Nationalism

VERDICT 2019 Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic vs Nationalism SMITA GUPTA Samajwadi Party patron Mulayam Singh Yadav exchanges greetings with Bahujan Samaj Party supremo Mayawati during their joint election campaign rally in Mainpuri, on April 19, 2019. Photo: PTI In most of the 26 constituencies that went to the polls in the first three phases of the ongoing Lok Sabha elections in western Uttar Pradesh, it was a straight fight between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that currently holds all but three of the seats, and the opposition alliance of the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Rashtriya Lok Dal. The latter represents a formidable social combination of Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims and Jats. The sort of religious polarisation visible during the general elections of 2014 had receded, Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, discovered as she travelled through the region earlier this month, and bread and butter issues had surfaced—rural distress, delayed sugarcane dues, the loss of jobs and closure of small businesses following demonetisation, and the faulty implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The Modi wave had clearly vanished: however, BJP functionaries, while agreeing with this analysis, maintained that their party would have been out of the picture totally had Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his message of nationalism not been there. travelled through the western districts of Uttar Pradesh earlier this month, conversations, whether at district courts, mofussil tea stalls or village I chaupals1, all centred round the coming together of the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD). -

Visitor Analytics Report

PMINDIA website (pmindia.gov.in) Visitor Analytics Report 30th April, 2016 – 13th May, 2016 The new website of PM India was launched on May 26, 2015. This report, highlighting the visitor analytics data of the website, has been prepared for submission to the Prime Minister’s Office by the National Informatics Centre (NIC). The purpose of this report is to understand the usage pattern of the website’s visitors as an input for the continual improvement of the website. Prepared by: National Informatics Centre May 13, 2016 pmindia.gov.in: Visitor Analytics Report 30 Apr to 13 May, 2016 Executive Summary • The total number of sessions for this time period are 1,58,785. • The average visit duration for this time period is 2 minute 05 seconds. • The website is being accessed across all three types of devices (Desktop/laptop, mobile and tablet); however, desktop was the most popular device used for visiting the website. • The most popular news update: 1. PM launches Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana at Ballia; 5 crore beneficiaries to be provided cooking gas connections • The most popular speech: 1. Simhasth Kumbh Mahaparv 2016: Some Glimpses • The most popular image: The Chief Minister of U.P, Shri Akhilesh Yadav meets the Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi to discuss drought situation, in New Delhi on May 07, 2016. Prepared by: National Informatics Centre May 13, 2016 pmindia.gov.in: Visitor Analytics Report 30 Apr to 13 May, 2016 Statistics at a glance 1,58,785 1,23,822 Total visits Number of unique visitors 20 May 06th Maximum pages Highest number -

A Report on (Findings, Mismanagment, Criminality

TO HON. CHAIRMAN & Secretary CENTRAL WAQF COUNCIL, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA, NEW DELHI A REPORT ON FINDINGS, MISMANAGMENT, CRIMINALITY, CORRUPTION & SUGGESTION IN U.P. SHIA CENTRAL WAQF BOARD, LUCKNOW, UP By Hand/courier/ SPEED POST/ Email CONFIDENCIAL /MOST URGENT “Once a waqf , always a waqf” Section 56 of Waqf Act 1995 By Adv. Dr. Syed Ejaz Abbas, LL.M., Ph.D. (Law) (Report/observations pursuant to section 9 and 96 of wakf Act 1995,) Mumbai 1 A REPORT ON (FINDINGS, MISMANAGMENT, CRIMINALITY, CORRUPTION, SUGGESTIONS & CONCLUSION ) ABOUT U.P. SHIA CENTRAL WAQF BOARD, LUCKNOW, UP I-N-D-E-X Pages & Relevant Enclosures/Exhibit S.N. Particulars/Details of Complaints, FIR pending, and un- Pages in Report investigated by CB-CID UP/ Status of few more Complaints & Relevant Enclosures/Exhibit 1 Complaint of Shri Shaukat Bharati, Allahabad, 3 --13 & Ex-“A” 2 List of Serious cases /FIR against Waseem Rizvi 14 --15 3 Criminal Case No. 716/2013 under sections 420, 467, 468, 16 471, 120 B, and 509 of IPC registered by C.B. –CID UP, pertaining to P.S. Shahganj, Agra, Waqf No. 37 & Exhibit-“B” 4 Case Crime no. 217/2013 u/s 420/467/468/471/120b I.P.C. 17 --18 P.S. Swarup Nagar Dist. Kanpur nagar, UP & Ex-“C”(Page to ) 5 FIR No. 244/2017 Hazaratganj Kotwali P.S. under section 19 --21 & 420, 120B, 419, 468 etc. the complaint is of one Muttawalli of the Waqf No. 2704 Ex-“D” ”(Page to ) 6 Case Crime No. 349/2013 & 347 Thana Qutubsher Dist. 21 & Saharanpur. -

In the Supreme Court of India Criminal Appellate

WWW.LIVELAW.IN 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. OF 2021 (Arising out of SLP(Crl.)No.2717 of 2021) MOHAMMAD AZAM KHAN Appellant(s) VERSUS THE STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH Respondent(s) WITH CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. OF 2021 (Arising out of SLP(Crl.)No. 2655 of 2021) O R D E R Leave granted. These appeals take exception to the judgment and order dated 26.11.2020 passed by the High Court of Judicature at Allahabad in Criminal Misc. Bail Application Nos. 27852 and 27990 of 2020 concerning the FIR No.980 of 2019 dated 06.12.2019 registered at P.S: Civil Lines, District Rampur, Uttar Pradesh for offences punishable under Sections 420, 467, 468, 471 and 120 of Indian Penal Code and FIR No. 04 dated 03.01.2019 registered at P.S: Ganj, District Rampur, Uttar Pradesh for offence punishable under Sections 193, 420, 467, 468, and 471 of Indian Penal Code. WWW.LIVELAW.IN 2 After hearing learned counsel for the parties and considering the fact that the investigation in connection with the stated offences has been completed and chargesheet has been filed on 27.05.2020 and that the Trial Court has taken cognizance of the offence, the continued custody of the appellants may not be necessary for the purpose of further investigation and trial. Indeed, if the appellants are to be released on bail in connection with stated offences, they must abide by all strict conditions as may be imposed by the Trial Court for releasing them on bail in terms of this order, including not to influence the witnesses or tamper with the prosecution evidence, in any manner. -

October 2016 Dossier

INDIA AND SOUTH ASIA: OCTOBER 2016 DOSSIER The October 2016 Dossier highlights a range of domestic and foreign policy developments in India as well as in the wider region. These include analyses of the ongoing confrontation between India and Pakistan, the measures by the government against black money and terrorism as well as the scenarios in India's mega-state Uttar Pradesh on the eve of crucial state elections in 2017, the 17th India-Russia Annual Summit and the Eighth BRICS Summit. Dr Klaus Julian Voll FEPS Advisor on Asia With Dr. Joyce Lobo FEPS STUDIES OCTOBER 2016 Part I India - Domestic developments • Confrontation between India and Pakistan • Modi: Struggle against black money + terrorism • Uttar Pradesh: On the eve of crucial elections • Pollution: Delhi is a veritable gas-chamber Part II India - Foreign Policy Developments • 17th India-Russia Annual Summit • Eighth BRICS Summit Part III South Asia • Outreach Summit of BRICS Leaders with the Leaders of BIMSTEC 2 Part I India - Domestic developments Dr. Klaus Voll analyses the confrontation between India and Pakistan, the measures by the government against black money and terrorism as well as the scenarios in India's mega-state Uttar Pradesh on the eve of crucial state elections in 2017 and the extreme pollution crisis in Delhi, the National Capital ReGion and northern India. Modi: Struggle against black money + terrorism: 500 and 1000-Rupee notes invalidated Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed on the 8th of November 2016 the nation in Hindi and EnGlish. Before he had spoken to President Pranab Mukherjee and the chiefs of the army, navy and air force. -

Salient Points of Speech by BJP National President, Shri Amit Shah Addressing a Public Meeting at Ramleela Maidan, Mahavidya

Salient Points of Speech by BJP National President, Shri Amit Shah Addressing a Public Meeting at Ramleela Maidan, Mahavidya Saraswati Kund Road, Mathura (Uttar Pradesh) Saturday, 04 February 2017 Salient Points of Speech Given by BJP National President Shri Amit Shah In Mathura, UP This election of UP is not an election to choose MLA or to change the Chief Minister, it is the election for changing the fate of the state, this election is for development and to bring change in the UP: Amit Shah ********** Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi led central government of Bharatiya Janata Party within two and half years has brought more than 100 public-welfare schemes and through these plans, we have worked to raise every poor lives: Amit Shah ********** Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi implements several schemes for the development of Uttar Pradesh but Akhilesh Yadav government, do not let these plans to reach the people of UP: Amit Shah ********** Akhilesh Yadav, is asking Prime Minister when will the good days come in UP, I am telling you, Akhilesh ji when you will go, then immediately the good days will come, you have blocked the good days: Amit Shah ********** One has looted the country and the other has looted the state both these princes cannot develop UP, UP development can only be done by the BJP led by Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi: Amit Shah ********** Within a week after the formation of the BJP government the illegal occupation on the land of the government and poor will be freed from the land mafia and they will be chased outside UP: Amit Shah ********** Now Akhilesh Yadav and Rahul Gandhi are promising of good governance in Uttar Pradesh I want to ask them that the promise that you are making here then what did you do in the last five years, you should give the answer: Amit Shah ********** The government which cannot stop murder and rape, such deplorable events, they have no right to rule in UP: Amit Shah ********** Politics should not be based on caste or religion, There will be rule of law in UP after the formation of the BJP government. -

Rahul Regrets Misquoting SC

Follow us on: facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 @TheDailyPioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 WORLD 12 SPORT 15 Published From MONEY RULES US TO SANCTION NATIONS FOR NEYMAR RETURNS AS DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL BHUBANESWAR IMPORTING IRANIAN OIL RANCHI RAIPUR CHANDIGARH THE ROOST PSG BEAT MONACO 3-1 DEHRADUN HYDERABAD VIJAYWADA Late City Vol. 155 Issue 109 LUCKNOW, TUESDAY APRIL 23, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable ARSHAD IS UNDERSTATED: VIDYA} BALAN } 14 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com Rahul regrets misquoting SC But Cong president repeats ‘Chowkidar chor’ hai in Amethi PNS n NEW DELHI/AMETHI formation campaign” being led of executive power and a lead- by senior BJP functionaries as ing example of the corruption ongress president Rahul well as the Government that of the BJP Government led by CGandhi on Monday the December 14 last year Prime Minister Modi, which expressed regret in the judgment gave a “clean chit” to deserves to be investigated Supreme Court over his the Modi Government on the thoroughly by a Joint remarks attributing certain Rafale deal. Parliamentary Committee and comments against Prime He also referred to a media proceeded against thereafter”. Minister Narendra Modi on the interview by Prime Minister Away from the SC pro- basis of a recent order of the top Narendra Modi in which he ceedings, Rahul once again court in the Rafale deal case, had said the apex court had raked up his often-repeated but wasted no time in repeat- given a clean chit to the poll theme of alleged corrup- ing his “Chowkidar chor” jibe Government in the Rafale deal. -

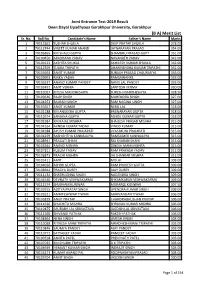

(B A) Merit List Sr

Joint Entrance Test-2019 Result Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur (B A) Merit List Sr. No. Roll No. Candidate's Name Father's Name Marks 1 70112362 TUSHAR SHUKLA DILIP PRATAP SHUKLA 378.00 2 70112744 VINEET KUMAR ANAND JAYNARAYAN PRASAD 354.00 3 70106865 KM SHALU GUPTA SHAMBHU PRASAD GUPT 351.00 4 70100450 ARADHANA YADAV NAVANATH YADAV 342.00 5 70100123 AKSHITA SHUKLA AKHILESH KUMAR SHUKLA 342.00 6 70112359 TULIKA TRIPATHI DHARMENDRA KUMAR TRIPATHI 342.00 7 70103663 ANKIT KUMAR SUBASH PRASAD CHAURASIYA 336.00 8 70109993 RINKA YADAV RAMSAWANRE 333.00 9 70103537 ANAND KUMAR PANDEY NAND LAL PANDEY 333.00 10 70103492 AMIT VERMA SANTOSH VERMA 330.00 11 70110057 RITESH MADDHESHIYA SURESH MADDHESHIYA 328.50 12 70109646 RAJIV SINGH MAHENDRA SINGH 327.00 13 70104253 BALRAM SINGH RAM NAGINA SINGH 327.00 14 70103657 ANKIT KUMAR NEBU LAL 318.00 15 70101188 KM ANGEERA GUPTA BRIJNARAYAN GUPTA 318.00 16 70110574 SANJANA GUPTA ASHOK KUMAR GUPTA 318.00 17 70101984 KM KAJAL MISHRA SHAILESH PRASAD MISHRA 315.00 18 70104164 AVNISH KUMAR YADAV VINOD KUMAR 315.00 19 70104188 AYUSH KUMAR PRAJAPATI VYAS MUNI PRAJAPATI 315.00 20 70104259 BASHISHTHA KANNAUJIYA RAMSUMER KANNAUJIYA 315.00 21 70108941 PRAGATI SHAHI RAJ SHARAN SHAHI 315.00 22 70103544 ANAND MISHRA DINESH MANI MISHRA 315.00 23 70107811 KUSUM YADAV RAM PRAKASH YADAV 312.00 24 70108873 PRACHI MISHRA JAI SHANKAR MISHRA 312.00 25 70103411 AMIT MOLAI 309.00 26 70104026 ASHOK GUPTA RAM PRAVESH GUPTA 309.00 27 70108944 PRAGYA DUBEY AJAY DUBEY 309.00 28 70111134 SHATRUGHNA SINGH NAGENDRA -

Lok Sabha ___ Bulletin – Part I

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN – PART I (Brief Record of Proceedings) ___ Tuesday, June 18, 2019/Jyaistha 28, 1941(Saka) ___ No. 2 11.00 A.M. 1. Observation by the Speaker Pro tem* 11.03 A.M. 2. Oath or Affirmation The following members took the oath or made the affirmation, signed the Roll of Members and took their seats in the House:- Sl. Name of Member Constituency State Oath/ Language No. Affirmation 1 2 3 4 5 6 1. Shri Santosh Pandey Rajnandgaon Chhattisgarh Oath Hindi 2. Shri Krupal Balaji Ramtek(SC) Maharashtra Oath Marathi Tumane 3. Shri Ashok Mahadeorao Gadchiroli-Chimur Maharashtra Oath Marathi Nete (ST) 4. Shri Suresh Pujari Bargarh Odisha Oath Odia 5. Shri Nitesh Ganga Deb Sambalpur Odisha Oath English 6. Shri Er. Bishweswar Mayurbhanj (ST) Odisha Oath English Tudu 7. Shri Ve. Viathilingam Puducherry Puducherry Oath Tamil 8. Smt. Sangeeta Kumari Bolangir Odisha Oath Hindi Singh Deo 9. Shri Sunny Deol Gurdaspur Punjab Oath English *Original in Hindi, for details, please see the debate of the day. 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 10. Shri Gurjeet Singh Aujla Amritsar Punjab Oath Punjabi 11. Shri Jasbir Singh Gill Khadoor Sahib Punjab Affirmation Punjabi (Dimpa) 12. Shri Santokh Singh Jalandhar (SC) Punjab Oath Punjabi Chaudhary 13. Shri Manish Tewari Anandpur Sahib Punjab Oath Punjabi 14. Shri Ravneet Singh Bittu Ludhiana Punjab Oath Punjabi 15. Dr. Amar Singh Fatehgarh Sahib Punjab Oath Punjabi (SC) 16. Shri Mohammad Faridkot (SC) Punjab Oath Punjabi Sadique 17. Shri Sukhbir Singh Badal Firozpur Punjab Oath Punjabi 18. Shri Bhagwant Mann Sangrur Punjab Oath Punjabi 19.