Judgment Altamas Kabir, Cji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

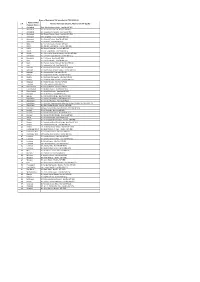

S N. Name of TAC/ Telecom District Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms

Name of Nominated TAC members for TAC (2020-22) Name of TAC/ S N. Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms] Hon’ble MP (LS/RS) Telecom District 1 Allahabad Prof. Rita Bahuguna Joshi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 2 Allahabad Smt. Keshari Devi Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 3 Allahabad Sh. Vinod Kumar Sonkar, Hon’ble MP (LS) 4 Allahabad Sh. Rewati Raman Singh, Hon’ble MP (RS) 5 Azamgarh Smt. Sangeeta Azad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 6 Azamgarh Sh. Akhilesh Yadav, Hon’ble MP (LS) 7 Azamgarh Sh. Rajaram, Hon’ble MP (RS) 8 Ballia Sh. Virendra Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 9 Ballia Sh. Sakaldeep Rajbhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 10 Ballia Sh. Neeraj Shekhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 11 Banda Sh. R.K. Singh Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 12 Banda Sh. Vishambhar Prasad Nishad, Hon’ble MP (RS) 13 Barabanki Sh. Upendra Singh Rawat, Hon’ble MP (LS) 14 Barabanki Sh. P.L. Punia, Hon’ble MP (RS) 15 Basti Sh. Harish Dwivedi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 16 Basti Sh. Praveen Kumar Nishad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 17 Basti Sh. Jagdambika Pal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 18 Behraich Sh. Ram Shiromani Verma, Hon’ble MP (LS) 19 Behraich Sh. Brijbhushan Sharan Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 20 Behraich Sh. Akshaibar Lal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 21 Deoria Sh. Vijay Kumar Dubey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 22 Deoria Sh. Ravindra Kushawaha, Hon’ble MP (LS) 23 Deoria Sh. Ramapati Ram Tripathi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 24 Faizabad Sh. Ritesh Pandey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 25 Faizabad Sh. Lallu Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 26 Farrukhabad Sh. -

You Have Made It to Phase 3 of ET Campus Stars 4.0. Now Get Ready

CONGRATULATIONS TO THE SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES You have made it to Phase 3 of ET Campus Stars 4.0. Now get ready for an exciting online assessment. Phase 3 is a Group Exercise and Leadership Competency Index Test that will evaluate you on your inter-personal abilities, group dynamics skills, leadership traits, and personality attributes. Please note the next steps: The online session details (including date & time) for Phase 3 assessment would be shared with you directly over the email. The shortlisted candidates have to share their details for verification, such as: •Name •Registered mobile number •College name •College ID card photo •Engineering batch •Current engineering year Please mail the above details at [email protected] latest by 29 June 2021. The list is in alphabetical order and does not endorse/promote any rank/marks Name College City A Benjimen BV Raju Institute of Technology Narsapur Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam - College A.Divija Sri Tirupati of Engineering Gautam Buddha University - College of Aadarsh Kumar Shrivastav Greater Noida Engineering Aadya Srivastava Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology Bhubaneshwar Oriental Institute of Science & Technology - Aakarsh Nema Bhopal Bhopal Aakash Garg Maharaja Agrasen Institute of Technology Delhi Aakash Ravindra Shinde NBN sinhgad school of Engineering - Pune Pune Aakash Yadav IMS Engineering College Ghaziabad Cummins College of Engineering for Women - Aaliyah Ahmed Pune Pune Chandigarh Group of Colleges - College of Aarju Tripathi Greater Mohali Engineering Lovely -

29 April Page 1

Evening daily Imphal Times Regd.No. MANENG /2013/51092 Volume 6, Issue 432 Sunday, April 28, 2019 Maliyapham Palcha kumsing 3416 Cyclone FANI likely to hit North Chief Minister N. Biren inspect Chadong East including Manipur tomorrow incident site; announces ban on unauthorized IT News boat at tourism related spot (with inputs from PIB) Imphal, April 29, IT News Imphal, April 29, The Cyclonic Storm FANI, which has its root at Bay of Chief Minister N. Birenshing Bengal is likely to hit the today announced banned to North Eastern states of India the use of unauthorized local including Manipur by the made boat at lakes which are evening of May 1, PIB report tourism related sites of the says as per notification by the state. The announcement was Ministry of Earth Science. A made after inspecting the freak storm possibly an impact Ramrei/Chadong Village today of the Cyclonic FANI morning where three persons yesterday killed 3 persons including a woman were killed including a woman while in yesterday freak storm while enjoying Boat ride at Chadong they were enjoying boat ride. artificial lake. Many trees and The fierce storm that lasted for houses were also destroyed at Bengal & neighbourhood hours and into a Very Severe around 30 minutes blown the various places in the nearly 30 moved northwards with a Cyclonic Storm duringboats that the three were riding minutes deadly storm. Report speed of about 04 kmph in last subsequent 24 hours. It is very and as it turn upside-down said that wind speed reached six hours and lay centred at likely to move bodies the trio could not be 50-60 km per hour and came 0830 hrs IST of 29th April, 2019 northwestwards till May 1 found till today morning. -

Paper Teplate

Volume-03 ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) Issue-09 RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary September-2018 www.rrjournals.com [UGC Listed Journal] Succession planning in Politics: A Study in Indian context 1Dr. Ella Mittal & *2Parvinder Kaur 1Assistant professor, Department of Basic & Applied sciences, Punjabi university Patiala (India) *2Research scholar, Department of Basic & Applied sciences, Punjabi university Patiala (India) ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History The present study is about the succession planning in politics. The study traced the dynasty Published Online: 07 September 2018 of succession in various political parties. Political parties at central and state level are discussed in order to examine the succession planning among the political families. Politics is Keywords considered as business rather than a profession. BJP and regional parties are seen as legacy, Political dynasty, Political blaming Congress for family succession as their culture but have also proliferated their parties, Succession planning families in heading chief positions. Nowadays politics of India is passing through the *Corresponding Author transition and „promoting the family‟ appears to be a consistent part of their life. Leaders need Email: saini.parvinder80[at]gmail.com to change their behaviour of selfishness in order to boost the country to grow and prosper without any hindrance of corruption. 1. Introduction responsibility to ensure the „stability of tenure of personnel‟. Fayol believed that key positions would end being occupied by Succession planning is a process of thinking and unskilled or ill-prepared people if the need is ignored earlier at assuming new incumbent as a successor of the key position in proper time (Rothwell 2001). -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic Vs Nationalism

VERDICT 2019 Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic vs Nationalism SMITA GUPTA Samajwadi Party patron Mulayam Singh Yadav exchanges greetings with Bahujan Samaj Party supremo Mayawati during their joint election campaign rally in Mainpuri, on April 19, 2019. Photo: PTI In most of the 26 constituencies that went to the polls in the first three phases of the ongoing Lok Sabha elections in western Uttar Pradesh, it was a straight fight between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that currently holds all but three of the seats, and the opposition alliance of the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Rashtriya Lok Dal. The latter represents a formidable social combination of Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims and Jats. The sort of religious polarisation visible during the general elections of 2014 had receded, Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, discovered as she travelled through the region earlier this month, and bread and butter issues had surfaced—rural distress, delayed sugarcane dues, the loss of jobs and closure of small businesses following demonetisation, and the faulty implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The Modi wave had clearly vanished: however, BJP functionaries, while agreeing with this analysis, maintained that their party would have been out of the picture totally had Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his message of nationalism not been there. travelled through the western districts of Uttar Pradesh earlier this month, conversations, whether at district courts, mofussil tea stalls or village I chaupals1, all centred round the coming together of the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD). -

Visitor Analytics Report

PMINDIA website (pmindia.gov.in) Visitor Analytics Report 30th April, 2016 – 13th May, 2016 The new website of PM India was launched on May 26, 2015. This report, highlighting the visitor analytics data of the website, has been prepared for submission to the Prime Minister’s Office by the National Informatics Centre (NIC). The purpose of this report is to understand the usage pattern of the website’s visitors as an input for the continual improvement of the website. Prepared by: National Informatics Centre May 13, 2016 pmindia.gov.in: Visitor Analytics Report 30 Apr to 13 May, 2016 Executive Summary • The total number of sessions for this time period are 1,58,785. • The average visit duration for this time period is 2 minute 05 seconds. • The website is being accessed across all three types of devices (Desktop/laptop, mobile and tablet); however, desktop was the most popular device used for visiting the website. • The most popular news update: 1. PM launches Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana at Ballia; 5 crore beneficiaries to be provided cooking gas connections • The most popular speech: 1. Simhasth Kumbh Mahaparv 2016: Some Glimpses • The most popular image: The Chief Minister of U.P, Shri Akhilesh Yadav meets the Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi to discuss drought situation, in New Delhi on May 07, 2016. Prepared by: National Informatics Centre May 13, 2016 pmindia.gov.in: Visitor Analytics Report 30 Apr to 13 May, 2016 Statistics at a glance 1,58,785 1,23,822 Total visits Number of unique visitors 20 May 06th Maximum pages Highest number -

Page11.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU SATURDAY, AUGUST 6, 2016 (PAGE 11) Sonia Gandhi Mulayam in poll mode, asks Akhilesh, US, allies to ‘aggressively’ steadily recuperating other leaders to pull up socks go after ISIS: Obama WASHINGTON, Aug 5: ment to pull the situation back NEW DELHI, Aug 5: LUCKNOW, Aug 5: birth anniversary of SP leader government. Two parties are from the brink. late Jnaneshwar Mishra. trying to orchestrate riots in the US President Barack Obama Congress Chief Sonia Gandhi was making steady progress, two In a stern message to party “The US remains prepared Referring to youth workers state." has asserted that America and its days after she underwent a surgery to repair a shoulder injury, Sir workers, Samajwadi Party chief to work with Russia to try to in the party, Mulayam said the He stressed the need for giv- allies will continue to target the Ganga Ram Hospital, where she has been admitted, said today. Mulayam Singh Yadav today reduce the violence and new breed of party workers did ing special emphasis on youths Islamic State “aggressively” asked them to pull up their socks strengthen our efforts against "Mrs Sonia Gandhi has been shifted out of the ICU and is mak- not know the foundation of and farmers and said women for the 2017 Uttar Pradesh across all fronts, as he vowed to ISIS and Al-Qaeda in Syria, but ing steady progress in the hospital. 'samajwad' (socialism). should also be included in the Assembly polls and stop "grab- be relentless in the fight against so far Russia has failed to take "She was admitted under Dr Arup Basu and his team from "I have asked (chief minis- party working. -

October 2016 Dossier

INDIA AND SOUTH ASIA: OCTOBER 2016 DOSSIER The October 2016 Dossier highlights a range of domestic and foreign policy developments in India as well as in the wider region. These include analyses of the ongoing confrontation between India and Pakistan, the measures by the government against black money and terrorism as well as the scenarios in India's mega-state Uttar Pradesh on the eve of crucial state elections in 2017, the 17th India-Russia Annual Summit and the Eighth BRICS Summit. Dr Klaus Julian Voll FEPS Advisor on Asia With Dr. Joyce Lobo FEPS STUDIES OCTOBER 2016 Part I India - Domestic developments • Confrontation between India and Pakistan • Modi: Struggle against black money + terrorism • Uttar Pradesh: On the eve of crucial elections • Pollution: Delhi is a veritable gas-chamber Part II India - Foreign Policy Developments • 17th India-Russia Annual Summit • Eighth BRICS Summit Part III South Asia • Outreach Summit of BRICS Leaders with the Leaders of BIMSTEC 2 Part I India - Domestic developments Dr. Klaus Voll analyses the confrontation between India and Pakistan, the measures by the government against black money and terrorism as well as the scenarios in India's mega-state Uttar Pradesh on the eve of crucial state elections in 2017 and the extreme pollution crisis in Delhi, the National Capital ReGion and northern India. Modi: Struggle against black money + terrorism: 500 and 1000-Rupee notes invalidated Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed on the 8th of November 2016 the nation in Hindi and EnGlish. Before he had spoken to President Pranab Mukherjee and the chiefs of the army, navy and air force. -

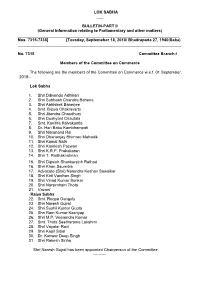

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6. -

Existence of Glass Ceiling in India

International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management 120 Volume-3, Issue-3, March-2020 www.ijresm.com | ISSN (Online): 2581-5792 Existence of Glass Ceiling in India Niraj Bharambe1, Sanjana Bhangale2 1Assistant Professor, Department of Human Resource, Shri D. D. Vispute College of Science Commerce and Management, Panvel, India 2Assistant Professor, Dept. of IT & CS, Pillai’s College of Arts Commerce and Management, Panvel, India Abstract: India is that the country within which unity within the towards family and career. Firstly, prime management diversity exits twenty-nine states with completely different concentrates on the on top of problems relating to ladies when religions, completely different customs, and completely different searching for the performance of the ladies at the geographical languages however the standing of girls in each state rather like similar in every term. the current standing ladies in Bharat is point at the time of the appraisal or promotion that is immoral. extremely sophisticated wherever some women are on the list of Since 1970, the definition of the ladies has been incessantly prime CEOs and politics. But, on the opposite hand, no correct dynamic in each field like politics, corporate, public sector, etc. facilities on the market for continued their education. Bharat still, Male invariably dominates the feminine. There ar could be a country wherever men and ladies are equal in rights distinguishes between male {and feminine and feminine} as an however in some cases, ladies bring home the bacon but a person example rather like that pink is that the color of female and blue below identical parameter. -

Modi's New India

Kolkata Seminar Invitation On 17th August, 2019 at 2 p.m. at Bharat Sabha Hall (Indian Association Hall, B. B. Ganguli Street, near its Crossing with Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata) Dear Friends, Indian Renaissance Institute and Indian Radical Humanist Association, West Bengal Unit are going to jointly organise a seminar on: 1. 2019 Election: BJP's Victory - A Challenge to Secular Polity, & 2. Party-less Democracy at Bharat Sabha Hall, Kolkata. The Speakers include Mr. Jahar Sarkar, IAS (Retd.) & former CEO, Doordarshan, Prof. Apurba Mukhopadhyay, former Prof. Bardhaman University & was attached to the Netaji Research Bureau, Mr. Pravin Patel, a social activist of fame, Dr. Bhabani Dikshit, journalist & IRI Member, Mr. N.D. Pancholi, well known Civil Rights lawyer & one of the Vice-Chairmen, IRI, Mr. Ajit Bhattacharyya, Life Trustee, IRI and Ms. Sangeeta Mall, former Managing Editor, The Radical Humanist. Prof. Miratun Nahar will preside over the 1st Session & Prof. Manju Ray over the 2nd. You are cordially invited to attend the seminar. For more details, please contact: Mr. Ajit Bhattacharyya. (M) 9433224517 Mahi Pal Singh Secretary, IRI In Memory of George Fernandes: His write up ‘On the threshold of a fascist state’: Preface: On the threshold of a fascist state George Fernandes (The recent 3rd June was remembered as privilege of associating with him in trade birth anniversary of veteran political leader unions movements as part of HMS (Hind George Fernandes who recently died this Mazdoor Sabha) during seventies. Generally year. Many friends paid glowing tributes to he came forcefully in support of civil liberties him. The eminent journalist Shri Jaishankar and democratic movements.