The Antigua and Barbuda Review of Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother/Motherland in the Works of Jamaica Kincaid

027+(5027+(5/$1' ,1 7+( :25.6 2) -$0$,&$ .,1&$,' 7pVLVÃGRFWRUDOÃSUHVHQWDGDÃSRU 6DEULQDÃ%UDQFDWR SDUDÃODÃREWHQFLyQÃGHOÃWtWXORÃGH 'RFWRUDÃHQÃ)LORORJLDÃ$QJOHVDÃLÃ$OHPDQ\D 'LULJLGDÃSRUÃODÃ'UDÃ.DWKOHHQÃ)LUWKÃ0DUVGHQ 3URJUDPDÃGHÃGRFWRUDGR 5HOHFWXUHVÃGHOÃ&DQRQÃ/LWHUDUL ELHQLRÃ 8QLYHUVLWDWÃGHÃ%DUFHORQD )DFXOWDWÃGHÃ)LORORJLD 'HSDUWDPHQWÃGHÃ)LORORJLDÃ$QJOHVDÃLÃ$OHPDQ\D 6HFFLyÃG¶$QJOpV %DUFHORQDÃ A Matisse, con infinito amore &RQWHQWV $&.12:/('*0(176 &+5212/2*< ,1752'8&7,21 &+$37(5Ã $WÃWKHÃ%RWWRPÃRIÃWKHÃ5LYHU: M/othering and the Quest for the Self &+$37(5Ã $QQLHÃ-RKQ: Growing Up Under Mother Empire &+$37(5Ã $Ã6PDOOÃ3ODFH: The Legacy of Colonialism in Post-Colonial Antigua &+$37(5Ã /XF\: Between Worlds &+$37(5Ã 7KHÃ$XWRELRJUDSK\ÃRIÃ0\Ã0RWKHU: The Decolonisation of the Body &+$37(5Ã 0\Ã%URWKHU: The Homicidal Maternal Womb Revisited &21&/86,21 %,%/,2*5$3+< $FNQRZOHGJPHQWV I give endless thanks to my dear friend and supervisor, Professor Kathleen Firth, for having encouraged the writing of this work and carefully revised it, as well as for suggestions that always respected my intentions. To Isabel Alonso I owe heavy doses of optimism in difficult times. Thanks for having been my best friend in my worst moments. I am infinitely grateful to Matteo Ciccarelli for the help, love and protection, the spiritual sustenance as well as the economic support during all these years, for preventing me from giving up and for always putting my needs before his. During the years I have been preparing this thesis, many people have accompanied me on the voyage to discovery of the wonderful mysteries of books. Thanks to Raffaele Pinto, Annalisa Mirizio and the other friends of the seminar on writing and desire for the enlightening discussions over shared drinks and crisps. -

The Choral Music of Noel Dexter

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-1-2015 A Jamaican Voice: The Choral Music of Noel Dexter Desmond A. Moulton University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, Music Theory Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Moulton, Desmond A., "A Jamaican Voice: The Choral Music of Noel Dexter" (2015). Dissertations. 112. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi A JAMAICAN VOICE: THE CHORAL MUSIC OF NOEL DEXTER by Desmond Moulton Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts August 2015 ABSTRACT A JAMAICAN VOICE: THE CHORAL MUSIC OF NOEL DEXTER by Desmond Moulton August 2015 As we approach the 21st-century, the world generally is moving away from the dominance of the European aesthetic toward a world music that owes much to the musical resources of the African-American tradition. Jamaica’s social and philosophical music belong mainly to that tradition, which includes the use of rhythms, timbral, and melodic resources that exist independently of harmony. Already in this century, Jamaicans have created two totally new music - nyabinghi, which performs a philosophical function and reggae, which performs a social function. -

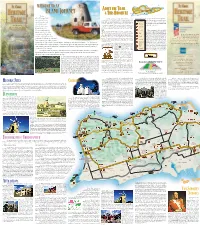

Island Journey Island Journey

WELCOME TO AN CHRISTIANSTED About the trail ST. CROIX ISLAND JOURNEY & this brochure FREDERIKSTED The St. Croix Heritage Trail As with many memorable journeys, there is no association with each site represent attributes found there, traverses the entire real beginning or end of the trail. You may want to start such as greathouse, windmill, nature, Key to Icons 28 mile length of St. your drive at either Christiansted or Frederiksted as a or viewscape. All St. Croix roads are not portrayed, so do not consider this Croix, linking the point of reference, or you can begin at a point close to Greathouse Your Guide to the where you’re staying. If you want to take it easy, you can a detailed road map. historic seaports of History, Culture, and Nature cover the trail in segments by following particular Sugar Mill of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands Frederiksted and subroutes, such as the “East End Loop,” delineated on the Christiansted with the map. Chimney Please remember to drive on the left, fertile central plain, the The Heritage Trail will take you to three levels of sites: a remnant traffic rule bequeathed by our full-service Attractions that can be toured: Visitation Ruin Danish past. The speed limit along the mountainous Northside, Sites, like churches, with irregular hours; and Points of Trail ranges between 25 and 35 mph, We are proud that the St. Croix Church unless otherwise noted. Seat belts are Heritage Trail has been designated and the arid East End. The r e Interest, which you can view, but are not open to the tl u B one of fifty Millennium Legacy Trails by public. -

Installation Ceremony Programme

Many scholars and activists, and many movements and moments, have shaped his mentality. Professor Sir Hilary Beckles shares a glimpse into this world of gestation and generosity with ten celebrations. CELEBRATION Symbol of liberty and freedom in the Caribbean and beyond...universal declaration of commitment to human rights. The Unknown Maroon, Port-Au-Prince, Haiti The Installation OF Professor Sir Hilary Beckles as Vice-Chancellor Of The University of the West Indies Professor Sir Hilary Beckles assumed office as Vice-Chancellor on May 1, 2015 Before assuming the office of been staged to popular acclaim. Vice-Chancellor of The University In the corporate community his of the West Indies on May footprint is well established. He is 1, 2015, Professor Sir Hilary a long serving director of Sagicor was Principal and Pro Vice- Financial Corporation, and has Chancellor of The University served as a director of its principal of the West Indies, Cave Hill subsidiaries Sagicor Jamaica Ltd, Campus, Barbados for thirteen and Sagicor Barbados Ltd. He is years(2002-2015). Sir Hilary a director of Cable and Wireless has emerged as a distinguished Barbados Ltd, and is Chairman of university administrator, The University of the West Indies internationally reputed Economic Press. Historian, and transformational leader in higher education.He Sir Hilary received his higher has had a spectacular journey education in the United Kingdom within the UWI, entering as a and graduated with a BA (Hons) temporary assistant lecturer in degree in Economic and Social 1979 at the Mona campus. In History from Hull University short time he was promoted to in 1976, and a PhD from the senior lecturer and then to the same university in 1980. -

The Antigua and Barbuda Review of Books Volume 8 Number 1 Fall 2015

THE ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA REVIEW OF BOOKS VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 FALL 2015 Tim Hector on Gregson Davis Gregson Davis on Tim Hector Lawrence Jardine on Tim Hector Tim Hector on Jamaica Kincaid Dorbrene O’Marde on Tim Hector Joanne Hillhouse on Dorbrene O’marde Hazra Medica on Marie-Elena John Tim Hector on Novelle Richards Edgar Lake on Henry Redhead Yorke Charles Ephraim on Tim Hector Lowell Jarvis on Tim Hector Tim Hector at Brown University And Much Much More ... THE ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA REVIEW OF BOOKS A Publication of the Antigua and Barbuda Studies Association Volume 8 • Number 1 • Fall 2015 Copyright © 2015 Antigua and Barbuda Studies Association Editorial Board: Ian Benn, Joanne Hillhouse, Paget Henry, Edgar Lake, Adlai Murdoch, Ermina Osoba, Elaine Olaoye, Mali Olatunji, Vincent Richards Paget Henry, Editor The Antigua and Barbuda Studies Association was founded in 2006 with the goal of raising local intellectual awareness by creating a field of Antigua and Barbuda Studies as an integral part of the larger field of Caribbean Studies. The idea for such an interdisciplinary field grew out of earlier “island conferences” that had been organized by the University of the West Indies, School of Continuing Edu- cation, in conjunction with the Political Culture Society of Antigua and Barbuda. The Antigua and Barbuda Review of Books is an integral part of this effort to raise local and regional intellectual awareness by generating conversations about the neglected literary traditions of Antigua and Barbuda through reviews of its texts. Manuscripts: the manuscripts of this publication must be in the form of short reviews of books or works of art dealing with Antigua and Barbuda. -

Unique-Expressions-Magazine-2016

The 7th Annual Multicultural Showcase Elizabeth Burns Once again, we have successfully brought together the members of our Caribbean-American Commu- nity in South Florida for these events celebrating National Caribbean-American Heritage Month. Events started with the Kick-Off Meet & Greet held in Miramar, followed by the Caribbean American Heritage Awards Banquet & Gala and now with the grand finale, the 7Th Annual Caribbean American Exhibition & Festival, a showcase of entrepreneurs, entertainers, and family enjoyment. The Exhibition & Festival is attended and supported by not only the Caribbean Community, but also by the general community from Palm Beach, Broward, Miami-Dade counties and from the Caribbean Islands. It provides a platform for businesses on which to promote and market their products and ser- vices to the local community, it also allows many entertainers to showcase their talents, thereby leading to booking opportunities. As you can see, we are moving in leaps and bounds and adding new elements to the events each year. There is a full-fledged Island Food Pavilion and a Kid’s Zone. We also now have a larger stage, so that in the future we can have more entertainment and even some big name entertainers. The future looks very bright for our events. You will enjoy next year’s Exhibition & Festival even more, so make sure that you save the date, June 25, 2017 and keep in touch with our website CAHMUSA.com or join us on Facebook or other social media. Congratulations to the 8 individuals who were chosen to receive the Caribbean-American Heritage Awards for their outstanding service to their community and country. -

NOTE 160P.; Title in English and French, but Text All in English

DOCUMENT RESUME . ED 402 216 SO 025 716 TITLE Learning about Folklife: The U.S. Virgin Islands and Senegal. A Guide for Teachers and Students = Apprenons A Propos Des Traditions Culturelles: Les Iles Vierges Des Etats Unis Et Le Senegal. INSTITUTION Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies. PUB DATE [92] NOTE 160p.; Title in English and French, but text all in English. Accompanying videotape not included with ERIC copy. AVAILABLE FROM Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies, Smithsonian Institution, 955 L'Enfant Plaza, Suite 2600, Washington, DC 20560. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides.(For Teacher)(052) Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bands (Music); *Cultural Education; Dance; *Folk Culture; Food; Foreign Countries; Geography; Intermediate Grades; Musical Composition; Music Education; Oral Tradition; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Story Telling IDENTIFIERS Festivals; Folk Music; *Senegal; *Virgin Islands ABSTRACT Developed as part of an educational kit that includes a four-part videotape, maps, photographs, and audio tapes, this guide gives teacher preparation information, objectives, teaching strategies, and student activities for each of 3 lessons in 4 units: Unit 1, "Introduction to Folklife," presents a definition in lesson 1, "What is Folklife?" In lesson 2 students examine photographs to further their understanding of folklife. Lesson 3 offers interviewing techniques for collecting cultural data. Unit 2, "Geography & Cultural History," uses maps, written descriptions of the Virgin Islands, recipes, and 6 student activity sheets as resources for lessons on "Map Study"; "Traditional Foodways"; and "Cooking Up Your Own Heritage." Unit 3, "Music & Storytelling," asks students to watch a video segment and listen to a Sengalese storytelling tape as a basis for discussions and related activities. -

J. Gerstin Tangled Roots: Kalenda and Other Neo-African Dances in the Circum-Caribbean

J. Gerstin Tangled roots: Kalenda and other neo-African dances in the circum-Caribbean In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 78 (2004), no: 1/2, Leiden, 5-41 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl JULIAN GERSTIN TANGLED ROOTS: KALENDA AND OTHER NEO-AFRICAN DANCES IN THE CIRCUM-CARIBBEAN In this article I investigate the early history of what John Storm Roberts (1972:26, 58) terms "neo-African" dance in the circum-Caribbean. There are several reasons for undertaking this task. First, historical material on early Caribbean dance and music is plentiful but scattered, sketchy, and contradic- tory. Previous collections have usually sorted historical descriptions by the names of dances; that is, all accounts of the widespread dance kalenda are treated together, as are other dances such as bamboula, djouba, and chica. The problem with this approach is that descriptions of "the same" dance can vary greatly. I propose a more analytical sorting by the details of descrip- tions, such as they can be gleaned. I focus on choreography, musical instru- ments, and certain instrumental practices. Based on this approach, I suggest some new twists to the historical picture. Second, Caribbean people today remain greatly interested in researching their roots. In large part, this article arises from my encounter, during eth- nographic work in Martinique, with local interpretations of one of the most famous Caribbean dances, kalenda.1 Martinicans today are familiar with at least three versions of kalenda: (1) from the island's North Atlantic coast, a virtuostic dance for successive soloists (usually male), who match wits with drummers in a form of "agonistic display" (Cyrille & Gerstin 2001; Barton 2002); (2) from the south, a dance for couples who circle one another slowly and gracefully; and (3) a fast and hypereroticized dance performed by tourist troupes, which invented it in the 1950s and 1960s. -

Inside Is Caribbean Today’S Special 15-Member Caricom Group, Outlining His Priorities As Supplement, Marking Jamaica’S 52Nd Incoming Chairman

PRESORTED JULy 2014 STANDARD ® U.S. POSTAGE PAID MIAMI, FL PERMIT NO. 7315 Tel: (305) 238-2868 1-800-605-7516 [email protected] [email protected] We cover your world Vol. 25 No. 8 www.caribbeantoday.com THE MULTI AWARD WINNING NEWS MAGAZINE WITH THE LARGEST PROVEN CIRCULATION IN FLORIDA GUARANTEED On his last day in office Thursday, United States Ambassador to Guyana, Brent Hardt, took time to address the recent verbal assault unleashed on him by Guyana’s Minister of Education Priya Manickchand and the country’s acting minister of foreign affairs. Page 11A Haitian Prime Minister embarks on an ambitious plan to become an “emerging coun - try” by 2030. Page 2A Newly elected Antigua and Barbuda Prime Minister Gaston Browne, addresses the InsIde Is CarIbbean Today’s speCIal 15-member Caricom group, outlining his priorities as supplemenT, markIng JamaICa’s 52nd incoming chairman. Page 7A annIversary of IndependenCe. INSIDE News ........................................................2A Bahamas ................................................12A Health ....................................................16A Feature ......................................................7A Entertainment ........................................13A Classifieds ............................................17A Viewpoint ................................................9A Food ........................................................14A Sports ......................................................18A Read CaRibbean Today onLine aT CaRibbeanToday.Com 2A -

The Resonance Report

THE RESONANCE REPORT CARIBBEAN TOURISM QUALITY INDEX About Resonance Resonance Consultancy Ltd. creates marketing Our future-focused visions, reports and strategies strategies, development plans, and tourism help our clients find their way forward, provide brands that shape the future of destinations and plans for action, and give officials, investors and developments around the world. the public reasons to believe. Our team has advised destinations, communities, The principals of Resonance have more than a half- cities and governments in more than 15 states century of development and tourism experience, and 70 countries. We provide leading public and have completed more than 100 visioning, and private sector organizations with visioning, strategy, planning, policy and branding projects for trend forecasting, marketing strategy, stakeholder destinations and communities around the world. engagement, economic development strategy, and Together, we’ve created an integrated process that tourism policy to help realize the full potential of helps both public and private sector clients look communities. ahead – ahead of the curve, around the corner or a decade from now. To learn more about Resonance From Bucharest to Brasilia, Hawai‘i to Haiti, we Consultancy and our services, please visit: have helped clients understand consumer trends, www.resonanceco.com influence policy, engage their communities, plan for the future, and market their unique destination. Chris Fair Richard Cutting-Miller Dianna Carr President and CEO Executive Vice-President Vice-President Contents 04 | INTRODUCTION 05 | A CONSUMER VIEW OF THE CARIBBEAN 07 | DESTINATIONS: REVIEWED, DISSECTED, SHARED 09 | KEY TENDS TAKEAWAY 12 | EXAMINING THE RANKINGS 13 | METHODOLOGY: THE SUPPLY SIDE ANALYSIS 14 | absoLUTE RANKINGS. -

2012-2013-Guide-To-The-Caribbean

COVER.pdf 1 12-04-26 3:16 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K WELCOME WHETHER YOU’RE LOOKING FOR A ROMANTIC FEATURES getaway, a fun family adventure, a culinary excursion or a cultural experience, the majes- Welcome 3 tic islands of the Caribbean cater to every One Big Kid’s Club 4-5 traveller‘s needs. The Caribbean Tourism Mother Nature Rocks 6-7 Organization welcomes you to explore and Love Blooms in the Caribbean 8 enjoy all that its 33 member countries have to Gal Pals in the Tropics 10-11 offer. Life’s a Beach 12-13 Each Caribbean country has its own soul Spa-tacular in the Caribbean 14-15 and flavour that attracts visitors from all over Rum – The Spirit of the Caribbean 16-18 the world. Boasting four languages - English, Top 10 Reasons to Visit the Caribbean 19-20 Dutch, French, and Spanish - travellers can strike up a conversation What’s Happening 21-23 with locals while strolling down streets filled with remarkable history Caribbean Map 32-33 or walking along the pink, black, white, or golden sandy beaches. They lose themselves in the smooth rich tones of reggae, the DESTINATIONS rhythmic sounds of the steel pan, and dance with passion to salsa, calypso, merengue, compas, or zouk! Anguilla 24 If trying innovative cuisine is a must on vacation, then entice Antigua & Barbuda 25 your palate with traditional Caribbean dishes such as shark and Aruba 26 bake, oil-down, pepperpot, souse, jerk chicken, goat water, The Islands of the Bahamas 27 calaloo or mouth-watering tropical treats such as coconut water, Barbados 28 mangoes, star-apples and guavas. -

The Hummingbird

The Hummingbird Volume 2 Issue 2 February 2015 The ECLAC Port of Spain Newsletter It’s Carnival! During the four-day holiday of carnival festivities in Martinique, activ- ity on the island nearly comes to a standstill. The parades and parties start on Big Sunday (Dimanche Gras) and finish on Ash Wednesday when the car- nival effigy, the ―Vaval‖ King, is burned. In Puerto Rico, one of the tradi- tions of carnival is the appearance of the "vejigantes", which is a colourful cos- tume traditionally representing the devil or, simply, evil. Vejigantes carry blown cow bladders with which they make sounds and hit people throughout the processions. Masqueraders on the stage at Queen’s Park Undoubtedly the largest in the Savannah, Port of Spain. region, Trinidad and Tobago carnival is an annual event held on the Monday and ONCE again there is a special vibe in time, expect to participate in dance Tuesday before Ash Wednesday. the air across the Caribbean, as coun- parties around the city, and see colour- The ―mas‖ tradition started in tries gear-up for pre-Lenten carnival ful costumes. the late 18th century with French plan- celebrations. Aruba, Haiti, Cuba, Cura- Curacao carnival is one of the tation owners organizing masquerades cao, Dominica, Dominican Republic, oldest in the Caribbean (starting since and balls before beginning the Lenten Guadeloupe, Guyana, Martinique, the 19th century in private clubs as fast. Indentured labourers and slaves, Puerto Rico and – chief among them – masquerade parties), and features fan- who could not take part in Carnival, Trinidad and Tobago will be looking to tastic parades, floats, costumes and formed their own parallel celebration.