To: Congressional Aides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muon Tomography Sites for Colombian Volcanoes

Muon Tomography sites for Colombian volcanoes A. Vesga-Ramírez Centro Internacional para Estudios de la Tierra, Comisión Nacional de Energía Atómica Buenos Aires-Argentina. D. Sierra-Porta1 Escuela de Física, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga-Colombia and Centro de Modelado Científico, Universidad del Zulia, Maracaibo-Venezuela, J. Peña-Rodríguez, J.D. Sanabria-Gómez, M. Valencia-Otero Escuela de Física, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga-Colombia. C. Sarmiento-Cano Instituto de Tecnologías en Detección y Astropartículas, 1650, Buenos Aires-Argentina. , M. Suárez-Durán Departamento de Física y Geología, Universidad de Pamplona, Pamplona-Colombia H. Asorey Laboratorio Detección de Partículas y Radiación, Instituto Balseiro Centro Atómico Bariloche, Comisión Nacional de Energía Atómica, Bariloche-Argentina; Universidad Nacional de Río Negro, 8400, Bariloche-Argentina and Instituto de Tecnologías en Detección y Astropartículas, 1650, Buenos Aires-Argentina. L. A. Núñez Escuela de Física, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga-Colombia and Departamento de Física, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida-Venezuela. December 30, 2019 arXiv:1705.09884v2 [physics.geo-ph] 27 Dec 2019 1Corresponding author Abstract By using a very detailed simulation scheme, we have calculated the cosmic ray background flux at 13 active Colombian volcanoes and developed a methodology to identify the most convenient places for a muon telescope to study their inner structure. Our simulation scheme considers three critical factors with different spatial and time scales: the geo- magnetic effects, the development of extensive air showers in the atmosphere, and the detector response at ground level. The muon energy dissipation along the path crossing the geological structure is mod- eled considering the losses due to ionization, and also contributions from radiative Bremßtrahlung, nuclear interactions, and pair production. -

UNHCR Colombia Receives the Support of Private Donors And

NOVEMBER 2020 COLOMBIA FACTSHEET For more than two decades, UNHCR has worked closely with national and local authorities and civil society in Colombia to mobilize protection and advance solutions for people who have been forcibly displaced. UNHCR’s initial focus on internal displacement has expanded in the last few years to include Venezuelans and Colombians coming from Venezuela. Within an interagency platform, UNHCR supports efforts by the Government of Colombia to manage large-scale mixed movements with a protection orientation in the current COVID-19 pandemic and is equally active in preventing statelessness. In Maicao, La Guajira department, UNHCR provides shelter to Venezuela refugees and migrants at the Integrated Assistance Centre ©UNHCR/N. Rosso. CONTEXT A peace agreement was signed by the Government of Colombia and the FARC-EP in 2016, signaling a potential end to Colombia’s 50-year armed conflict. Armed groups nevertheless remain active in parts of the country, committing violence and human rights violations. Communities are uprooted and, in the other extreme, confined or forced to comply with mobility restrictions. The National Registry of Victims (RUV in Spanish) registered 54,867 displacements in the first eleven months of 2020. Meanwhile, confinements in the departments of Norte de Santander, Chocó, Nariño, Arauca, Antioquia, Cauca and Valle del Cauca affected 61,450 people in 2020, as per UNHCR reports. The main protection risks generated by the persistent presence of armed groups and illicit economies include forced recruitment of children by armed groups and gender- based violence – the latter affecting in particular girls, women and LGBTI persons. Some 2,532 cases of GBV against Venezuelan women and girls were registered by the Ministry of Health between 1 January and September 2020, a 41.5% increase compared to the same period in 2019. -

The Mineral Industry of Colombia in 1998

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF COLOMBIA By David B. Doan Although its mineral sector was relatively modest by world foundation of the economic system of Colombia. The standards, Colombia’s mineral production was significant to its constitution guarantees that investment of foreign capital shall gross domestic product (GDP), which grew by 3.2% in 1997. have the same treatment that citizen investors have. The A part of this increase came from a 4.4% growth in the mining constitution grants the State ownership of the subsoil and and hydrocarbons sector.1 In 1998, however, Colombia ended nonrenewable resources with the obligation to preserve natural the year in recession with only 0.2% growth in GDP, down resources and protect the environment. The State performs about 5% from the year before, the result of low world oil supervision and planning functions and receives a royalty as prices, diminished demand for exports, terrorist activity, and a economic compensation for the exhaustion of nonrenewable decline in the investment stream. The 1998 GDP was about resources. The State believes in privatization as a matter of $255 billion in terms of purchasing power parity, or $6,600 per principle. The Colombian constitution permits the capita. Colombia has had positive growth of its GDP for more expropriation of assets without indemnification. than six decades and was the only Latin American country not The mining code (Decree 2655 of 1988) covers the to default on or restructure its foreign debt during the 1980's, prospecting, exploration, exploitation, development, probably owing in no small part to the conservative monetary beneficiation, transformation, transport, and marketing of policy conducted by an independent central bank. -

Indigenous Inclusion/Black Exclusion: Race, Ethnicity and Multicultural Citizenship in Latin America

J. Lat. Amer. Stud. 37, 285–310 f 2005 Cambridge University Press 285 doi:10.1017/S0022216X05009016 Printed in the United Kingdom Indigenous Inclusion/Black Exclusion: Race, Ethnicity and Multicultural Citizenship in Latin America JULIET HOOKER Abstract. This article analyses the causes of the disparity in collective rights gained by indigenous and Afro-Latin groups in recent rounds of multicultural citizenship re- form in Latin America. Instead of attributing the greater success of indians in win- ning collective rights to differences in population size, higher levels of indigenous group identity or higher levels of organisation of the indigenous movement, it is argued that the main cause of the disparity is the fact that collective rights are adjudicated on the basis of possessing a distinct group identity defined in cultural or ethnic terms. Indians are generally better positioned than most Afro-Latinos to claim ethnic group identities separate from the national culture and have therefore been more successful in winning collective rights. It is suggested that one of the potentially negative consequences of basing group rights on the assertion of cultural difference is that it might lead indigenous groups and Afro-Latinos to privilege issues of cultural recognition over questions of racial discrimination as bases for political mobilisation in the era of multicultural politics. Introduction Latin America as a region exhibits high degrees of racial inequality and dis- crimination against Afro-Latinos and indigenous populations. This is true despite constitutional and statutory measures prohibiting racial discrimi- nation in most Latin American countries. In addition to legal proscriptions of racism, in the 1980s and 1990s many Latin American states implemented multicultural citizenship reforms that established certain collective rights for indigenous groups. -

Pdf | 319.67 Kb

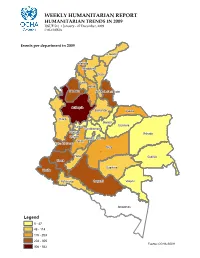

WEEKLY HUMANITARIAN REPORT HUMANITARIAN TRENDS IN 2009 ISSUE 51| 1 January - 27 December, 2009 COLOMBIA Events per department in 2009 La Guajira Atlántico Magdalena Cesar Sucre Bolívar Córdoba Norte de Santander Antioquia Santander Arauca Chocó Boyacá Casanare Caldas Cundinamarca Risaralda Vichada Quindío Bogotá, D.C. To l i m a Valle del Cauca Meta Huila Guainía Cauca Guaviare Nariño Putumayo Caquetá Vaupés Amazonas Legend 5 - 47 48 - 114 115 - 203 204 - 305 Fuente: OCHA-SIDIH 306 - 542 WEEKLY HUMANITARIAN REPORT HUMANITARIAN TRENDS IN 2009 ISSUE 51| 1 January - 27 December, 2009 COLOMBIA Events in 2009 | Weekly trend* 350 325 175 96 132 70 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 0 1 3 5 7 9 111315171921232527293133353739414345474951 Events in 2009 | Total per department Number of events per category Antioquia 542 Nariño 305 Massacres, Displaceme Forced Cauca 296 125 nt events, recruit., 63 Valle del Cauca 261 Road 81 Córdoba 269 blocks, 55 Norte de Santander 250 Caquetá 225 Arauca 203 Atlántico 157 Armed Tolima 160 conf., 825 Bolivar 150 Meta 146 APM/UXO Bogotá D.C. 109 Victims, Huila 106 670 Cesar 114 Sucre 93 Homicide Putumayo 86 of PP, 417 Risaralda 83 Magdalena 85 Santander 78 Chocó 78 Guaviare 71 La Guajira 68 Kidnappin Vaupés 47 g, 157 Attacks on Caldas 36 civ., 1.675 Quindío 27 Cundinamarca 23 Casanare 22 Boyacá 18 Quindío 12 Vichada 7 Guanía 5 0 300 600 WEEKLY HUMANITARIAN REPORT HUMANITARIAN TRENDS IN 2009 ISSUE 51| 1 January - 27 December, 2009 COLOMBIA Main events in 2009 per month • January: Flood Response Plan mobilised US$ 3.1 million from CERF. -

Petrographic and Geochemical Studies of the Southwestern Colombian Volcanoes

Second ISAG, Oxford (UK),21-231911993 355 PETROGRAPHIC AND GEOCHEMICAL STUDIES OF THE SOUTHWESTERN COLOMBIAN VOLCANOES Alain DROUX (l), and MichelDELALOYE (1) (1) Departement de Mineralogie, 13 rue des Maraîchers, 1211 Geneve 4, Switzerland. RESUME: Les volcans actifs plio-quaternaires du sud-ouest de laColombie sontsitues dans la Zone VolcaniqueNord (NVZ) des Andes. Ils appartiennent tous B la serie calcoalcaline moyennement potassique typique des marges continentales actives.Les laves sont principalementdes andesites et des dacites avec des teneurs en silice variant de 53% il 70%. Les analyses petrographiqueset geochimiques montrent que lesphtfnomBnes de cristallisation fractionnee, de melange de magma et de contamination crustale sont impliquesil divers degres dans la gknkse des laves des volcans colombiens. KEY WORDS: Volcanology, geochemistry, geochronology, Neogene, Colombia. INTRODUCTION: This publication is a comparative of petrographical, geochemical and geochronological analysis of six quaternary volcanoes of the Northem Volcanic Zone of southwestem Colombia (O-3"N): Purace, Doiia Juana, Galeras, Azufral, Cumbal and Chiles.The Colombian volcanic arc is the less studied volcanic zone of the Andes despite the fact that some of the volcanoes, whichlie in it, are ones of the most actives inthe Andes, i.e. Nevado del Ruiz, Purace and Galeras. Figure 1: Location mapof the studied area. Solid triangles indicatethe active volcanoes. PU: PuracC; DJ: Doiia Juana; GA: Galeras;AZ :Azufral; CB: Cumbal; CH: Chiles; CPFZ: Cauca-Patia Fault Zone; DRFZ: Dolores-Romeral Fault Zone;CET: Colombia-Ecuador Trench. Second ISAG, Oxford (UK),21 -231911993 The main line of active volcanoes of Colombia strike NNEi. It lies about 300 Km east of the Colombia- Ecuador Trench, the underthrusting of the Nazca plate beneath South America The recent volcanoes are located 150 ICm above a Benioff Zone whichdips mtward at25"-30", as defined by the work ofBaraangi and Isacks (1976). -

Colombia 6 August 2021 Post-Conflict Violence in Cauca KEY FIGURES

Briefing note Colombia 6 August 2021 Post-conflict violence in Cauca KEY FIGURES OVERVIEW KEY FINDINGS In 2016, the Colombian Government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of The demobilisation of the FARC-EP did not end armed violence in Cauca. 5,527 Colombia (FARC-EP) signed a peace agreement. While the demobilisation Several armed groups continue to operate, and new groups have appeared. of the FARC-EP was seen as a first step towards pacifying many regions of In Cauca, as incentives for the continued existence of armed groups remain PEOPLE DISPLACED Colombia, armed groups continued and even escalated the violent attacks in in place – including illegal mining and areas for the cultivation, processing, BETWEEN JANUARY– several regions, including the Cauca department. and transport of coca and marijuana – these groups have entered into APRIL 2021 confrontation to take over these resources. In Cauca, some armed groups remained in the territory, while others were formed after the signing of the peace agreement; additional groups entered Civilians are affected by these confrontations through displacement, the region to occupy territories abandoned by the FARC-EP. Confrontations confinement to their homes, and even death by armed groups in order 497 among these groups have resulted in forced displacement, confinement of to preserve territorial control. Human rights defenders and farmer, Afro- PEOPLE FORCIBLY local populations to their homes, and limited access for humanitarian workers. descendant, and indigenous leaders are at particular risk of being killed or CONFINED BY ARMED These armed groups have also attacked civilians – especially human rights displaced because of their visibility within communities and their rejection of GROUPS BETWEEN defenders and indigenous and Afro-descendant leaders. -

Inter-American Court on Human Rights

INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS ADVISORY OPINION OC-23/17 OF NOVEMBER 15, 2017 REQUESTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF COLOMBIA THE ENVIRONMENT AND HUMAN RIGHTS (STATE OBLIGATIONS IN RELATION TO THE ENVIRONMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF THE PROTECTION AND GUARANTEE OF THE RIGHTS TO LIFE AND TO PERSONAL INTEGRITY: INTERPRETATION AND SCOPE OF ARTICLES 4(1) AND 5(1) IN RELATION TO ARTICLES 1(1) AND 2 OF THE AMERICAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS) the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (hereinafter “the Inter-American Court” or “the Court”), composed of the following judges: Roberto F. Caldas, President Eduardo Ferrer Mac-Gregor Poisot, Vice President Eduardo Vio Grossi, Judge Humberto Antonio Sierra Porto Judge Elizabeth Odio Benito, Judge Eugenio Raúl Zaffaroni, Judge, and L. Patricio Pazmiño Freire, Judge also present, Pablo Saavedra Alessandri, Secretary, and Emilia Segares Rodríguez, Deputy Secretary, pursuant to Article 64(1) of the American Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter “the American Convention” or “the Convention”) and Articles 70 to 75 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court (hereinafter “the Rules of Procedure”), issues the following advisory opinion, structured as follows: - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PRESENTATION OF THE REQUEST ........................................................................................ 4 II. PROCEEDING BEFORE THE COURT ...................................................................................... 6 III. JURISDICTION AND ADMISSIBILITY ............................................................................. -

Plan Para La Atención De Emergencias En El Municipio De Popayán

REPÚBLICA DE COLOMBIA ALCALDÍA DE POPAYÁN DEPARTAMENTO DEL CAUCA PLAN PARA LA ATENCIÓN DE EMERGENCIAS EN EL MUNICIPIO DE POPAYÁN COMITÉ LOCAL PARA LA PREVENCIÓN Y ATENCIÓN DE DESASTRES –CLOPAD– Popayán, Julio de 2003 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 1. OBJETIVOS 1.1. OBJETIVO GENERAL 1.2. OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS 2. MONOGRAFÍA DEL MUNICIPIO DE POPAYÁN 2.1. ASPECTOS FÍSICOS 2.1.3. LOCALIZACIÓN GEOGRÁFICA 2.1.4. LÍMITES 2.1.5. COORDENADAS 2.1.6. CLIMATOLOGÍA 2.1.7. HIDROGRAFÍA 2.1.8. ÁREA DEL MUNICIPIO 2.1.8.1. Suelo Urbano 2.1.8.2. Suelo Rural 2.1.8.3. Suelo de Expansión 2.2. ASPECTOS POLÍTICOS Y ADMINISTRATIVOS 2.2.3. FUNDACIÓN DEL MUNICIPIO 2.2.4. CATEGORIZACIÓN DEL MUNICIPIO 2.2.5. DIVISIÓN POLÍTICA DEL MUNICIPIO 2.2.5.1. Sector Urbano 2.2.5.2. Sector Rural 2.2.6. POBLACIÓN 2.2.7. SERVICIOS PÚBLICOS 2.2.8. SECTOR SALUD 2.2.9. SECTOR EDUCACIÓN 2.2.9.1. Sector Urbano 2.2.9.2. Sector Rural 2.2.9.3. Educación Superior 2.2.10. RECREACIÓN Y DEPORTE 2.2.11. RECREACIÓN Y CULTURA 2.2.12. SERVICIOS ADMINISTRATIVOS PÚBLICOS 2.2.13. BANCOS Y CORPORACIONES 2.2.14. ÁREAS DE AFLUENCIA MASIVA DE PÚBLICO 2.2.15. PROVEEDORES DE EQUIPOS MÉDICOS 2.2.16. PROVEEDORES DE MEDICAMENTOS 3. IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LAS AMENAZAS 3.1. AMENAZA DE ORÍGEN NATURAL 3.1.1 AMENAZA SÍSMICA 3.1.1.1 Sistema de Fallas – Municipio de Popayán 3.1.2 AMENAZA POR DESLIZAMIENTOS 3.1.2.1. Sector Urbano 3.1.2.2. -

190205 USAID Colombia Brief Final to Joslin

COUNTRY BRIEF I. FRAGILITY AND CLIMATE RISKS II.COLOMBIA III. OVERVIEW Colombia experiences very high climate exposure concentrated in small portions of the country and high fragility stemming largely from persistent insecurity related to both longstanding and new sources of violence. Colombia’s effective political institutions, well- developed social service delivery systems and strong regulatory foundation for economic policy position the state to continue making important progress. Yet, at present, high climate risks in pockets across the country and government mismanagement of those risks have converged to increase Colombians’ vulnerability to humanitarian emergencies. Despite the state’s commitment to address climate risks, the country’s historically high level of violence has strained state capacity to manage those risks, while also contributing directly to people’s vulnerability to climate risks where people displaced by conflict have resettled in high-exposure areas. This is seen in high-exposure rural areas like Mocoa where the population’s vulnerability to local flooding risks is increased by the influx of displaced Colombians, lack of government regulation to prevent settlement in flood-prone areas and deforestation that has Source: USAID Colombia removed natural barriers to flash flooding and mudslides. This is also seen in high-exposure urban areas like Barranquilla, where substantial risks from storm surge and riverine flooding are made worse by limited government planning and responses to address these risks, resulting in extensive economic losses and infrastructure damage each year due to fairly predictable climate risks. This brief summarizes findings from a broader USAID case study of fragility and climate risks in Colombia (Moran et al. -

Afro-Colombians from Slavery to Displacement

A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE AND EXCLUSION: AFRO-COLOMBIANS FROM SLAVERY TO DISPLACEMENT A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Sascha Carolina Herrera, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. October 31, 2012 A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE AND EXCLUSION: AFRO-COLOMBIANS FROM SLAVERY TO DISPLACEMENT Sascha Carolina Herrera, B.A. MALS Mentor: Kevin Healy, Ph.D. ABSTRACT In Colombia, the Afro-Colombian population has been historically excluded and marginalized primarily due to the legacy of slavery deeply embedded within contemporary social and economic structures. These structures have been perpetuated over many generations of Afro-Colombians, who as a result have been caught in a recurring cycle of poverty throughout their history in Colombia. In contemporary Colombia, this socio-economic situation has been exacerbated by the devastating effects of various other economic and social factors that have affected the Colombian society over half century and a prolonged conflict with extensive violence involving the Colombian state, Paramilitaries, and Guerrillas and resulting from the dynamics of the war on drugs and drug-trafficking in Colombian society. In addition to the above mentioned factors, Afro-Colombians face other types of violence, and further socio-economic exclusion and marginalization resulting from the prevailing official development strategies and U.S. backed counter-insurgency and counter-narcotics strategies and programs of the Colombian state. ii Colombia’s neo-liberal economic policies promoting a “free” open market approach involve the rapid expansion of foreign investment for economic development, exploitation of natural resources, and the spread of agro bio-fuel production such as African Palm, have impacted negatively the Afro-Colombian population of the Pacific coastal region. -

United States of America

United States of America Submission to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review Ninth Session of the Working Group on the UPR Human Rights Council 1-12 November 2010 THE NEGATIVE IMPACT OF U.S. FOREIGN POLICY ON HUMAN RIGHTS IN COLOMBIA, HAITI AND PUERTO RICO Submitted by: International Committee of National Lawyers Guild, Proceso de Comunidades Negras de Colombia, AFRODES USA, Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti, and RightRespect Endorsed by: Organizations: American Association of Jurists; Colegio de Abogados (Puerto Rico); Human Rights Advocates; Human Rights Caucus of Northeastern University School of Law; Latin American and Caribbean Community Center; MADRE; Metro Atlanta Task Force for the Homeless; National Conference of Black Lawyers/Chicago; Public Interest Projects; Three Treaties Task Force of the Social Justice Center of Marin; You.Me.We. Individuals: Joyce Carruth; Andrea Hornbein (MassDecarcerate); Amol Mehra (RightRespect); Ramona Ortega (Cidadao Global); Ute Ritz-Deutch, Ph.D. (Tompkins County Immigrant Rights Coalition); Nicole Skibola (RightRespect); Standish E. Willis (NCBL) 1 Executive Summary U.S. foreign policy relationships and assistance to Colombia, Haiti and Puerto Rico have resulted in human rights violations in those countries. For 10 years, Plan Colombia, a U.S. aid program to the Colombian government, has been in effect. Until 2007, 80 % of the $6.7 billion has been spent on the military. This has resulted in massive loss of life, internal displacement, a food crisis and economic instability, particularly in indigenous and communities of Afro-descendents. We oppose the U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement and urge U.S. legislators to cease further military and fumigations operations and refuse to certify Colombia as being in compliance with human rights standards.