Architectural Depictions on the Column of Marcus Aurelius Elizabeth Wolfram Thill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act

The Straw that Broke the Camel's Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act ERIC C. RUSNAK* The public lands of the United States have always provided the arena in which we Americans have struggled to fulfill our dreams. Even today dreams of wealth, adventure, and escape are still being acted out on these far flung lands. These lands and the dreams-fulfilled and unfulfilled-which they foster are a part of our national destiny. They belong to all Americans. 1 I. INTRODUCTION For some Americans, public lands are majestic territories for exploration, recreation, preservation, or study. Others depend on public lands as a source of income and livelihood. And while a number of Americans lack awareness regarding the opportunities to explore their public lands, all Americans attain benefits from these common properties. Public land affect all Americans. Because of the importance of these lands, heated debates inevitably arise regarding their use or nonuse. The United States Constitution grants to Congress the "[p]ower to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the... Property belonging to the United States." 2 Accordingly, Congress, the body representing the populace, determines the various uses of our public lands. While the Constitution purportedly bestows upon Congress sole discretion to manage public lands, the congressionally-enacted Antiquities Act conveys some of this power to the president, effectively giving rise to a concurrent power with Congress to govern public lands. On September 18, 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Proclamation 69203 under the expansive powers granted to the president by the Antiquities Act4 ("the Act") establishing, in the State of Utah, the Grand * B.A., Wittenberg University, 2000; J.D., The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, 2003 (expected). -

100% Personalized Custom Headstones & Monuments

HOW TO ORDER 100% Personalized Custom Headstones & Monuments Rome Monument offers you unlimited possibilities for your eternal resting place by completely personalizing a cemetery monument just for you…and just the way you want! Imagine capturing your life’s interests and passions in granite, making your custom monument far more meaningful to your family and for future generations. Since 1934, Rome Monument has showcased old world skills and stoneworking artistry to create totally unique, custom headstones and monuments. And because we cut out the middleman by making the monuments in our own facility, your cost may be even less than what other monument companies, cemeteries and funeral homes charge. Visit a cemetery and you’ll immediately notice that many monuments and headstones look surprisingly alike. That’s because they are! Most monument companies, cemeteries and funeral homes sell you stock monuments out of a catalog. You can mix and match certain design elements, but you can’t really create a truly personalized monument. Now you can create a monument you love and that’s as unique as the individual being memorialized. It starts with a call to Rome Monument. ROME MONUMENT • www.RomeMonuments.com • 724-770-0100 Rome Monument Main Showroom & Office • 300 West Park St., Rochester, PA WHAT’S PASSION What is truly unique and specialYour about you or a loved one? What are your interests? Hobbies? Passions? Envision how you want future generations of your family to know you and let us capture the essence of you in an everlasting memorial. Your Fai Your Hobby Spor Music Gardening Career Anima Outdoors Law Enforcement Military Heritage True Love ADDITIONAL TOPICS • Family • Ethnicity • Hunting & Fishing • Transportation • Hearts • Wedding • Flowers • Angels • Logos/Symbols • Emblems We don’t usee stock monument Personalization templates and old design catalogs to create your marker, monument, Process or mausoleum. -

Violence Against Women on the Column of Marcus Aurelius

Violence Against Women on the Column of Marcus Aurelius The Column of Marcus Aurelius is an imperial Roman monument of uncertain date, like- ly either 176 or 180 CE. Its elements (pedestal, spiral frieze, and statue) and its content (a mili- tary narrative) are largely modeled on the earlier Column of Trajan. One major difference be- tween the columns is that the Column of Marcus Aurelius shows physical violence much more often and more explicitly than the Column of Trajan. This pattern of increased violence on the Column of Marcus Aurelius extends into non-military contexts that involve women. On the Column of Trajan, women never appear alone: they are unthreatened and accompanied by other women and by husbands and/or children. Meanwhile on the Column of Marcus Aurelius, women are more often isolated and sometimes victims of rape and murder. Only one scene on the Col- umn of Marcus Aurelius appears to represent intact unthreatened families. In this scene, XVII, emperor Marcus Aurelius stands on an upper register, while a group of non-Romans gathers on the lower register. The group is composed of families, many with young children. Eugen Petersen, a German scholar, documented the column’s frieze, publishing a series of photographs and descriptions in 1896. In his companion to the frieze, Petersen sug- gests that “perhaps” scene XVII may represent families being separated, though he gives no evi- dence for this claim (Petersen vol. 1, 59). More recently, Paul Zanker has analyzed the scene as part of his work on women and children on the Column of Marcus Aurelius. -

Five Good Emperors Nerva – Marcus Aurelius HIS 207 Oakton Community College Mitilineos November 17, 2011 Reminders

Five good emperors Nerva – Marcus Aurelius HIS 207 Oakton Community College Mitilineos November 17, 2011 Reminders All material due by 11/29/2011 Final study guide – 11/29/2011 Today: ◦ Film ◦ Boudicca ◦ Five good emperors Boudicca and the Iceni Roman Britain C.E. 60 The evidence ◦ Tacitus Agricola ◦ Archaeology not helpful Iceni ◦ Celtic tribe in East Anglia ◦ farming Prasutagus, king of the Iceni Women among the Iceni ◦ power and positions of prestige ◦ Owned land ◦ Right to divorce Prasutagus ◦ Client/king ◦ Left kingdom to two daughters and Nero Roman law prohibits inheritance by women Members of ruling class enslaved Boudicca flogged, her daughters raped The Iceni look to Boudicca for leadership Revolt begins Supported by neighboring tribes, the Iceni numbered about 100,000 Attacked Camulodunum (Cambridge) and Colchester Successful for awhile due to guerilla tactics, use of chariots, lack of respect Last victory at Londinium (London) 230,000 faced smaller Roman force (Midlands – location unknown) 70,000 killed as Roman weapons and tactics under Paulinas prevail Suicide c. 61/62 Nerva 96-98 Period of five good emperors generally prosperous Chosen by senate Recalled exiles Modified taxes Tolerated Christians Adopted Trajan as his successor Purchased land from wealthy and rented them to the needed Promoted public education including poor children Trajan 98-117 Born in Spain Father was a consul Patrician status Adopted by Nerva in 97 Extended the empire As emperor Deified Nerva Optimus Augustus – the -

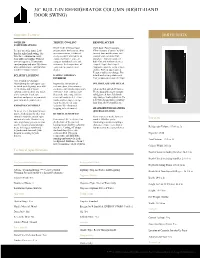

30” Built-In Refrigerator Column (Right-Hand Door Swing)

30” BUILT-IN REFRIGERATOR COLUMN (RIGHT-HAND DOOR SWING) Signature Features JBRFR30IGX OVER 250 TRINITY COOLING REMOTE ACCESS CONFIGURATIONS Revel in the trinity of food Open door. Power outages. Freezer or refrigerator. Left- preservation: three zones, three Filter changes. Connect to WiFi hand or right-hand swing. One, precision sensors, calibrated for real-time notifications and two, three columns in a row. every second. Fortified by an control your columns from Four different widths. With 12 exposed air tower, you can anywhere. Tap and swipe on one-unit options, 75 two-unit conquer humidity levels and both iOS and Android devices. combinations and over 250 three- customize the temperature of <sup>1</sup><br><sup>1 unit combinations, configuration each zone to your deepest Appliance must be set to remote is where bespoke begins. desires. enable. WiFi & app required. Features subject to change. For ECLIPTIC LIGHTING DARING OBSIDIAN details and privacy statement, INTERIOR visit jennair.com/connect.</sup> Live beyond the shadow. Abandoning the dark spots cast Inspired by the beauty of SOLID GLASS AND METAL by dated puck lighting, over 650 volcanic glass, this industry- LEDs frame and fill your exclusive dark finish erupts with All-metal bin and shelf frames. column, coming alive at a touch reflective, high-contrast style. Thick, naturally odor-resistant of the controls. Each zone Reject the unfeeling, lifeless solid glass. A forcefield at the awakens and pulses as you mold vessel of harsh steel. Let fine edge that prevents spillovers. To your column to your desires. foods and beverages emerge hell with cheap plastic in luxury from the interior of your door bins, shelves and liners. -

Vigiles (The Fire Brigade)

insulae: how the masses lived Life in the city & the emperor Romans Romans in f cus With fires, riots, hunger, disease and poor sanitation being the order of the day for the poor of the city of Rome, the emperor often played a personal role in safeguarding the people who lived in the city. Source 1: vigiles (the fire brigade) In 6 AD the emperor Augustus set up a new tax and used the proceeds to start a new force: the fire brigade, the vigiles urbani (literally: watchmen of the city). They were known commonly by their nickname of spartoli; little bucket-carriers. Bronze water Their duties were varied: they fought fires, pump, used by enforced fire prevention methods, acted as vigiles, called a police force, and even had medical a sipho. doctors in each cohort. British Museum. Source 2: Pliny writes to the emperor for help In this letter Pliny, the governor of Bithynia (modern northern Turkey) writes to the emperor Trajan describing the outbreak of a fire and asking for the emperor’s assistance. Pliny Letters 10.33 est autem latius sparsum, primum violentia It spread more widely at first because of the venti, deinde inertia hominum quos satis force of the wind, then because of the constat otiosos et immobilestanti mali sluggishness of the people who, it is clear, stood around as lazy and immobile spectatores perstitisse; et alioqui nullus spectators of such a great calamity. usquam in publico sipo, nulla hama, nullum Furthermore there was no fire-engine or denique instrumentumad incendia water-bucket anywhere for public use, or in compescenda. -

15Th-17Th Century) Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary (15Th-17Th Century) Edited by Giovanna Siedina

45 BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI Giovanna Siedina Giovanna Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World Civilization in the Slavic World (15th-17th Century) Civilization in the Slavic World of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Essays on the Spread (15th-17th Century) edited by Giovanna Siedina FUP FIRENZE PRESUNIVERSITYS BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI ISSN 2612-7687 (PRINT) - ISSN 2612-7679 (ONLINE) – 45 – BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI Editor-in-Chief Laura Salmon, University of Genoa, Italy Associate editor Maria Bidovec, University of Naples L’Orientale, Italy Scientific Board Rosanna Benacchio, University of Padua, Italy Maria Cristina Bragone, University of Pavia, Italy Claudia Olivieri, University of Catania, Italy Francesca Romoli, University of Pisa, Italy Laura Rossi, University of Milan, Italy Marco Sabbatini, University of Pisa, Italy International Scientific Board Giovanna Brogi Bercoff, University of Milan, Italy Maria Giovanna Di Salvo, University of Milan, Italy Alexander Etkind, European University Institute, Italy Lazar Fleishman, Stanford University, United States Marcello Garzaniti, University of Florence, Italy Harvey Goldblatt, Yale University, United States Mark Lipoveckij, University of Colorado-Boulder , United States Jordan Ljuckanov, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria Roland Marti, Saarland University, Germany Michael Moser, University of Vienna, Austria Ivo Pospíšil, Masaryk University, Czech Republic Editorial Board Giuseppe Dell’Agata, University of Pisa, Italy Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World (15th-17th Century) edited by Giovanna Siedina FIRENZE UNIVERSITY PRESS 2020 Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World (15th- 17th Century) / edited by Giovanna Siedina. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2020. -

Publications

Year Journal Volume Page Title PMID Authors Rapid non-uniform adaptation to Xue, Jenny Y; Zhao, Yulei; Aronowitz, Jordan; Mai, Trang T; Vides, Alberto; conformation-specific KRAS(G12C) Qeriqi, Besnik; Kim, Dongsung; Li, Chuanchuan; de Stanchina, Elisa; Mazutis, 2020 Nature 577 421-425 inhibition. 31915379 Linas; Risso, Davide; Lito, Piro Amor, Corina; Feucht, Judith; Leibold, Josef; Ho, Yu-Jui; Zhu, Changyu; Alonso- Curbelo, Direna; Mansilla-Soto, Jorge; Boyer, Jacob A; Li, Xiang; Giavridis, Theodoros; Kulick, Amanda; Houlihan, Shauna; Peerschke, Ellinor; Friedman, Senolytic CAR T cells reverse Scott L; Ponomarev, Vladimir; Piersigilli, Alessandra; Sadelain, Michel; Lowe, 2020 Nature 583 127-132 senescence-associated pathologies. 32555459 Scott W Ruscetti, Marcus; Morris 4th, John P; Mezzadra, Riccardo; Russell, James; Leibold, Josef; Romesser, Paul B; Simon, Janelle; Kulick, Amanda; Ho, Yu-Jui; Senescence-Induced Vascular Fennell, Myles; Li, Jinyang; Norgard, Robert J; Wilkinson, John E; Alonso- Remodeling Creates Therapeutic Curbelo, Direna; Sridharan, Ramya; Heller, Daniel A; de Stanchina, Elisa; 2020 Cell 181 424-441.e21 Vulnerabilities in Pancreas Cancer. 32234521 Stanger, Ben Z; Sherr, Charles J; Lowe, Scott W Uckelmann, Hannah J; Kim, Stephanie M; Wong, Eric M; Hatton, Charles; Therapeutic targeting of preleukemia Giovinazzo, Hugh; Gadrey, Jayant Y; Krivtsov, Andrei V; Rücker, Frank G; cells in a mouse model of NPM1 Döhner, Konstanze; McGeehan, Gerard M; Levine, Ross L; Bullinger, Lars; 2020 Science (New York, N.Y.) 367 586-590 mutant acute myeloid leukemia. 32001657 Vassiliou, George S; Armstrong, Scott A Ganesh, Karuna; Basnet, Harihar; Kaygusuz, Yasemin; Laughney, Ashley M; He, Lan; Sharma, Roshan; O'Rourke, Kevin P; Reuter, Vincent P; Huang, Yun-Han; L1CAM defines the regenerative origin Turkekul, Mesruh; Emrah, Ekrem; Masilionis, Ignas; Manova-Todorova, Katia; of metastasis-initiating cells in Weiser, Martin R; Saltz, Leonard B; Garcia-Aguilar, Julio; Koche, Richard; Lowe, 2020 Nature cancer 1 28-45 colorectal cancer. -

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents Eight Elements of Home Office Design 11 Home Office Furniture Ideas 15 - 57 Drawer Systems & Hinges 58 - 59 Folding & Sliding Door Systems 60 - 61 Further Products 62 - 63 www.hettich.com 3 How will we work in the future? This is an exciting question what we are working on intensively. The fact is that not only megatrends, but also extraordinary events such as a pandemic are changing the world and influencing us in all areas of life. In the long term, the way we live, act and furnish ourselves will change. The megatrend Work Evolution is being felt much more intensively and quickly. www.hettich.com 5 Work Evolution Goodbye performance society. Artificial intelligence based on innovative machines will relieve us of a lot of work in the future and even do better than we do. But what do we do then? That’s a good question, because it puts us right in the middle of a fundamental change in the world of work. The creative economy is on the advance and with it the potential development of each individual. Instead of a meritocracy, the focus is shifting to an orientation towards the strengths and abilities of the individual. New fields of work require a new, flexible working environment and the work-life balance is becoming more important. www.hettich.com 7 Visualizing a Scenario Imagine, your office chair is your couch and your commute is the length of your hallway. Your snack drawer is your entire pantry. Do you think it’s a dream? No! Since work-from-home is very a reality these days due to the pandemic crisis 2020. -

Dioscorides Extended: the Synonyma Plantarum Barbara Autor(Es)

Dioscorides extended: the Synonyma Plantarum Barbara Autor(es): Dalby, Andrew Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/45209 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-1721-3_1 Accessed : 11-Oct-2021 12:22:36 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Série Diaita Carmen Soares Scripta & Realia Cilene da Silva Gomes Ribeiro ISSN: 2183-6523 (coords.) Destina-se esta coleção a publicar textos resultantes da investigação de membros do projeto transnacional DIAITA: Património Alimentar da Lusofonia. As obras consistem em estudos aprofundados e, na maioria das vezes, de carácter interdisciplinar sobre uma temática fundamental para o desenhar de um património e identidade culturais comuns à população falante da língua portuguesa: a história e as culturas da alimentação. -

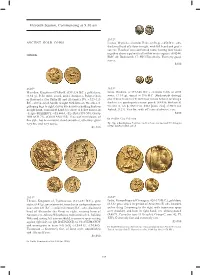

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

Mobile Column Lift System Is the Faster and Easier Choice for Your Maintenance Facility

MobileHEAVY DUTY Column LIFTING SYSTEMS Ergonomic FLEETVersatile Performance Productive Reliable FAST Dependable Mobile Buy America World Best Techs TM Legendary TM Red FireLRemoteE controlledADERHEAVY DUTY Battery Efficient MACHCareer Extender ENVIRONMENTALLY FRIENDLY TM EmployeeWireless Retention Patented Flex Innovative Adjustable www.rotarylift.com A Shown: MCHM419U1A00 / Wireless remote-controlled model N D D E VALIDAT TM WIRELESS CONTROLS FLEXMAX NO CABLES / NO CORDS REMOTE-CONTROLLED LIFTING Unmatched lifting versatility and flexibility with the mobility to monitor and adjust your columns anywhere in your shop. Premium FLEXMAXTM lifts provide wireless, remote-controlled flexibility LIFT UP TO 150,400 LBS. plus added operational controls at each column giving technicians the choice to work in the most comfortable, productive and efficient way possible. Ergonomic, wireless hand-held remote control walks the technician through the system set up. Status lights indicate standby or paired columns. Controller features include: • On/off power button with info screen • 2-speed joystick control with auto resume FLEXMAX419 • Single lower-to-lock button with E-stop control A N D 18,800 lbs. capacity column D TE VALIDA • Remote battery indicator Shown: MCHM419U100 • Press ProtectTM eliminates accidental button presses • Audible warning when operator is out of range TM Rotary FLEXMAX feature column capacities at • 99 system IDs eliminate communication interference 18,800 lbs. and 14,000 lbs. in multiple configurations. • Height and weight digital display gauge displays Service everything from light-duty passenger vehicles to • Software upgrades can be made wirelessly heavy-duty trucks. This electro-hydraulic system with WATCH THE adjustable lifting forks can be operated in both odd and PRODUCT VIDEO See how fast and even groups of columns.