The Case of Pratham in Bihar Rukmini Banerji WORKING PAPER October

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TACR: India: Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 41127 March 2011 India: Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector Prepared by MMM Group, Canada Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada For Road Construction Department Government of Bihar This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Asian Development Bank Road Construction Department Government of Bihar FINAL REPORT ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector March 2011 (Updated May 2011) Milestone Report MMM Group, Canada Asian Development Bank Road Construction Department Government of Bihar FINAL REPORT ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector March 2011 (Updated May 2011) Milestone Report MMM Group, Canada Final Report, March 2011 ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector 3 Final Report, March 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Introduction and TA Timeline ........................................................................................ 7 1.2 Interim Report and Mid-term Workshop ........................................................................ 8 1.3 Need for Changes in TA Scope of Work ...................................................................... -

Access-Of-Muslims-And-Other-Religious-Minorities-To-Rights-And-Freedoms-Bihar.Pdf

Access of Muslims and Other Religious Minorities to Rights and Freedoms – Bihar This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Provided they acknowledge the source, users of this content are allowed to remix, tweak, build upon and share for noncommercial purposes under the same original license terms. Some rights reserved Published by: Misaal - Centre for Equity Studies 24, Khazan Singh Building Adhchini, Aurobindo Marg New Delhi - 110 017, India Tel: +91 (0)11-26535961 / 62 Email: [email protected] Web : www.misaal.ngo Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/misaalfellowship Credits: This report has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. Minority Rights Group International provided technical help. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Misaal-CES, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency or of Minority Rights Group International. December 2016 Access of Muslims and Other Religious Minorities to Rights and Freedoms Bihar December 2016 i Executive Summary 1. This study aims to examine the access of religious minorities in the state of Bihar to minority rights - including to freedom of religion, life and security, and social, economic and cultural rights. The focus of the study is Muslims - by far the largest religious minority in Bihar, and India as a whole. We try to measure access to rights by mapping poor Muslims’ conditions as well as by examining the quality of state provisioning for them. This examination is based on (i) primary data on micro evidence on the condition of poor Muslims, collected from 5 sample sites of Muslim habitations in UP (Patna, Vaishali, Sitamarhi, Darbhanga and Madhubani districts) using household surveys (sample of 100 poor Muslim households at each site) and interviews and focus group discussions, as methods. -

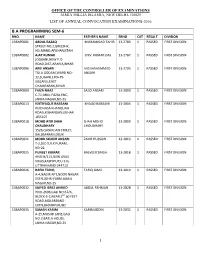

B.A Programming Sem-6

OFFICE OF THE CONTROLLER OF EXAMINATIONS JAMIA MILLIA ISLAMIA, NEW DELHI-110025 LIST OF ANNUAL CONVOCATION EXAMINATIONS-2016 B.A PROGRAMMING SEM-6 RNO NAME FATHER'S NAME ERNO CAT RESULT DIVISION 13BAP0001 ABDUL RAZAQ MUHAMMAD TAHIR 13-2783 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION STREET NO.2,GREESHK, HELMAND,AFGHANISTAN 13BAP0002 AJAY KUMAR SHIV KUMAR DAS 13-2787 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION JOGBANI,NEW P.O ROAD,DIST-ARARIA,BIHAR 13BAP0006 ARIF ANSARI AAS MAHAMMAD 13-2795 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION TOLA GODAM,WARD NO- ANSARI 12,SUGANLI,PO+PS- SUGANLI,EAST CHAMPARAN,BIHAR 13BAP0009 FAIZA NAAZ SAJID ANSARI 13-2800 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION C-71,ABUL FAZAL ENC, JAMIA NAGAR,ND-25 13BAP0013 ISHTIYAQUE RABBANI KHALID RABBANI 13-2804 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION RUIDHASA KHANQUAH ROAD,KISHANGANJ,BIHAR -855107 13BAP0018 MOHD ATIR SHAH SHAH MOHD 13-2809 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION CHAUDHARY CHOUDHARY 1526,QASIM JAN STREET, BALLIMARAN,DELHI 13BAP0021 MOHD SHAKIR ANSARI ZAKIR HUSSAIN 13-2813 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION T-2,SEC-9,R.K PURAM, ND-22 13BAP0025 PUNEET KUMAR BALVEER SINGH 13-2818 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION HNO-B/113,NEW AVAS VIKAS,KASHIPUR,U.S.N, UTTRAKHAND-244713 13BAP0026 RAFIA TARIQ TARIQ JAMIL 13-2819 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION A-4,NADIR APT,NOOR NAGAR EXTN,JOHRI FARM,JAMIA NAGAR,ND-25 13BAP0032 SAIYED IBREZ AHMED ABDUL REHMAN 13-2828 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION HNO-2696,GALI NO.67/A, BLOCK-E-2,NEAR 3RD 60 FEET ROAD,MOLARBAND EXTN,BADARPUR,ND 13BAP0035 SAMAN KARIM KARIMUDDIN 13-2832 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION A-25,MASJID LANE,GALI NO.7,BATLA HOUSE, JAMIA NAGAR,ND-25 1 OFFICE OF THE CONTROLLER -

147811611917220.Pdf

INTERVIEW ALUMNI WATCH GOVERNANCE @ WORK Shri Ajay Prakash Sawhney Shri TN Chaturvedi Mongolian official to be Secretary, MeitY Chairman, IIPA Trained in IIPA Vol No. 01 Inaugural Issue July-September 2019 IIPABuilding Capacity for Governance DIGESTPrice : ` 100 GANDHIJI’S TALISMAN “I will give you a talisman. Whenever you are in doubt or when the self becomes too much with you, apply the following test: Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man whom you may have seen and ask yourself if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him. Will he gain anything by it? Will it restore him to a control over his own life and destiny? In other words, will it lead to Swaraj for the hungry and spiritually starving millions? Then you will find your doubts and your self melting away” Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (October 2, 1869 to January 30, 1948) A Tribute by employees of Indian Institute of Public Administration 2019 Hon'ble President of India, Shri Ram Nath Kovind with IIPA Chairman, Shri TN Chaturvedi Hon'ble President of India, Shri Ram Nath Kovind with IIPA Director, Shri SN Tripathi Hon’ble Vice President of India and President of IIPA, Shri M Venkaiah Naidu addressing the audience during the 64th AGM, 2018 Editor in Chief Surendra Nath Tripathi Contents Vol No. 01 Issue No. 03 July-September 2019 Editor 4 Editorial Amitabh Ranjan 5 Alumni Watch Joint Editor 6-7 Interview Meghna Chukkath 8-9 Upfront Photography 10-11 Lead Story Shiv Charan 12-15 Gallery Printed at 16-20 Institute Watch New United Process New Delhi-110028 -

District Health Society Begusarai

DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN 2012-2013 DISTRICT HEALTH SOCIETY BEGUSARAI-1- Foreword This District Health Action Plan (DHAP) is one of the key instruments to achieve NRHM goals. This plan is based on health needs of the district and recognizing the importance of Health in the process of economic and social development and improving the quality of life of our citizens, the Government of India has resolved to launch the National Rural Health Mission to carry out necessary architectural correction in the basic health care delivery system. After a thorough situation analysis of district health scenario this document has been prepared. In the plan, it is addressing health care needs of rural poor especially women and children, the teams have analyzed the coverage of poor women and children with preventive and primitive interventions, barriers in access to health care and spread of human resources catering health needs in the district. The focus has also been given on current availability of health care infrastructure in public/NGO/private sector, availability of wide range of providers. This DHAP has been evolved through a participatory and consultative process, wherein community and other stakeholders have participated and ascertained their specific health needs in villages, problems in accessing health services, especially poor women and children at local level. The goals of the Mission are to improve the availability of and access to quality health care by people, especially for those residing in rural areas, the poor, women and children. I need to congratulate the department of Health and Family Welfare and State Health Society of Bihar for their dynamic leadership of the health sector reform programme and we look forward to a rigorous and analytic documentation of their experiences so that we can learn from them and replicate successful strategies. -

Bihar Towards a Development Strategy Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

Bihar Towards a Development Strategy Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The challenge of development in Bihar is enormous due to persistent poverty, complex social stratification, unsatisfactory infrastructure, and weak governance; these problems are well known, but not well understood. The people of Bihar civil society, businessmen, government officials, farmers, and politicians also struggle against an image problem that is deeply damaging to Bihars growth prospects. An effort is needed to change this perception, and to search for real solutions and strategies to meet Bihars development challenge. The main message of this report is one of hope. There are many success stories not well known outside Bihar that demonstrate its strong potential, and could in fact provide lessons for other regions. A boost to economic growth, improved social indicators, and poverty reduction will require a multi-dimensional development Public Disclosure Authorized strategy that builds on Bihars successes and draws on the underlying resilience and strength of its people. Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank, New Delhi Office 70 Lodi Estate, New Delhi - 110 003 Tel: 24617241 X 286; Fax: 24619393 http://www.worldbank.org.in http://www.vishwabank.org (Hindi website) http://www.vishwabanku.org (Kannada website) http://prapanchabank.org (Telugu website) A World Bank Report Bihar Towards a Development Strategy A World Bank Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a team led by Mark Sundberg and Mandakini Kaul, under the overall guid- ance of Sadiq Ahmed and Michael Carter, and with the advice of Stephen Howes and Kapil Kapoor. The peer reviewers were Sanjay Pradhan, Martin Ravallion, and Nicholas Stern. -

Functioning of Public Health Administration in Bihar

ISSN: 2230-9772 (Print); 2347-5927 (Online) Indian Journal of Applied and Clinical Sociology Volume 5: Issue 4, 2015. HDAWI Functioning of Public Health Administration in Bihar Dr. Krishna Kant Sharma Email: [email protected]; M: 9504782781. Abstract: The functioning of public health administration in Bihar was investigated during the period September 2013 to August 2015. A mixed method was adopted to study the manner they accomplished working on a system. In this paper, therefore, an institutional arrangements, socio-demographic, public health education, targets and achievements are described amidst a survey conducted in whole of Bihar. Key words: Public Health Administration in Bihar; Public Health System; System of Medicine; Health and Development. 1. Introduction: included collection of new data on public health coverage, parity in access, quality of health care, cost, and rural - urban Public health administration is a governmental organized gap in the public health sector. The aim was also to investigate attempt to improve the health of communities. Having certain the institutional arrangement and functioning of the public territorial implications it usually involves with public health health system in Bihar, with specifically studying the planning, financing, management, data, workforce, research, workforce status, demography, epidemiology, data education, and laws. In a defined territory, its various functions management, public health laws, policies, planning, process, included but not limited to demography, epidemiology, financing, and mandatory compliance, such as medico-legal, surveillance, preparedness, health informatics, public health citizen charter, blood, food, and drug safety. The objectives data, food-drug-blood safety, and ensuring various public were to integrate the scattered knowledge, literature, and health services and programs. -

Place-Making in Late 19Th And

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts TERRITORIAL SELF-FASHIONING: PLACE-MAKING IN LATE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURY COLONIAL INDIA A Dissertation in History by Aryendra Chakravartty © 2013 Aryendra Chakravartty Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 The dissertation of Aryendra Chakravartty was reviewed and approved* by the following: David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Director of Graduate Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Joan B. Landes Ferree Professor of Early Modern History & Women’s Studies Michael Kulikowski Professor of History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Head, Department of History Madhuri Desai Associate Professor of Art History and Asian Studies Mrinalini Sinha Alice Freeman Palmer Professor of History Special Member University of Michigan, Ann Arbor * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract My project, Territorial Self-Fashioning: “Place-Making” in Late 19th and Early 20th Century Colonial India, focuses on the province of Bihar and the emergence of a specifically place-based Bihari regional identity. For the provincial literati, emphasizing Bihar as an “organic” entity cultivated a sense of common belonging that was remarkably novel for the period, particularly because it implied that an administrative region had transformed into a cohesive cultural unit. The transformation is particularly revealing because the claims to a “natural” Bihar was not based upon a distinctive language, ethnicity or religion. Instead this regional assertion was partially instigated by British colonial politics and in part shaped by an emergent Indian national imagination. The emergence of a place-based Bihari identity therefore can only be explained by situating it in the context of 19th century colonial politics and nationalist sentiments. -

Sl. No. Centre Code Centre Name District Block Status Reasons 1 100935 PARAMPARA FOUNDATION Araria Araria Approved 2 98590 VIVEK

Sl. No. Centre Code Centre Name District Block Status Reasons 1 100935 PARAMPARA FOUNDATION Araria Araria Approved 2 98590 VIVEKANAND INSTITUTE OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Araria Araria Approved 3 97500 DIVYA DRISTI BHARAT Araria Araria Approved 4 97613 SARTHAK FOUNDATION Araria Araria Approved 5 100610 AMBEDKAR SEVA SANSTHAN Araria Araria Approved 6 100101 YOUTH FORUM FORBEGANJ Araria Bhargama Approved 7 97688 LOK PRAGATI SEWA SANSTHAN Araria Kursakata Approved 8 98440 DIVYA DRISTI BHARAT PALASI Araria Palasi Approved 9 96053 SMB CLOUD INFOTECH Arwal Arwal Approved 10 96459 CICAT INSTITUE OF MANAGEMENT AND TECHNOLOGFY Arwal Arwal Approved 11 97015 PRABHAT WELFARE TRUST Arwal Arwal Approved 12 97434 MAX COMPUTER CENTRE Arwal Kaler Approved 13 96154 PERFECT DATATECH PRIVATE LIMITED Arwal Karpi Approved 14 101431 ADARSH KRITI FOUNDATION Arwal Karpi Approved 15 97792 KUSUM DEVI MAHILA SAMAJIK SEVA SANSTHAN Arwal Sonbhadra Banshi Approved Surypur 16 99176 COMPTECH TRAINING & TECH. PVT LTD Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 17 97537 SAMAST MANAV JANKALYAN SANSTHAN Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 18 95637 DATA PRO COMPUTERS PVT LTD Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 19 95668 DATA PRO COMPUTERS PVT LTD Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 20 96121 QUESS CORP LTD Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 21 97428 PARMPARA FOUNDATION Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 22 96169 MAHEYUGE EDUCATIONAL WELFARE SOC. Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 23 99332 ZAKIRUDDIN GILANI MEMORIAL EDU. TRUST Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 24 99334 ZAKIRUDDIN GILANI MEMORIAL EDU. TRUST Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 25 100286 THITHOLI SAMAJIK EVAM SANSKRITIK DARPAN Aurangabad Aurangabad Approved 26 98128 Kriti Edify Pvt Ltd. Aurangabad Barun Approved 27 99872 NATIONAL RURAL DEVLOPMENT PROGRAM Aurangabad Barun Approved 28 101180 COMPTECH TRAINING & TECH. PVT LTD Aurangabad Daudnagar Approved 29 98262 Dharshan Institute of management & Pvt. -

Reviving the Administration: Bihar State, India, 2005-2009

Rohan Mukherjee Innovations for Successful Societies REVIVING THE ADMINISTRATION: BIHAR STATE, INDIA, 2005-2009 SYNOPSIS Nitish Kumar was elected chief minister of Bihar, India’s poorest state, in December 2005, when the state’s government was weighed down by two decades of institutional decline. He inherited a paralyzed administration, an unmotivated bureaucracy and a state that could not adequately respond to the needs of its people. His program of administrative reforms loosened the political stranglehold on the bureaucracy, decentralized authority within administrative hierarchies and brought government closer to citizens. By 2009, Bihar was seen as a pioneer among Indian states in some areas of administrative reform, especially in improving government accountability by implementing citizens’ rights to information. Two separate memos, “Coalition Building in a Divided Society” and “Clearing the Jungle Raj,” describe Kumar’s efforts to build a coalition for reform and to improve law and order in Bihar, respectively. Rohan Mukherjee drafted this policy note on the basis of interviews conducted in Patna, Bihar, in July 2009. INTRODUCTION pundits and academic observers had all but Nitish Kumar won a historic election in written off Bihar as a lost cause when Kumar December 2005 to become Bihar’s chief minister. emerged as an unexpected winner in the state At that time, popular opinion held that the Indian election. Through a strong reform effort in state had reached such a low point that the administration, infrastructure, and law and order, situation could not get much worse. This he was able to turn Bihar around in a relatively sentiment buoyed the new chief minister’s reform short period. -

Elementary Education in Bihar : an Overview 11-23 Literacy Rates in Bihar Elementary Education System Enrolment in Elementary Schools Incentive Schemes

1 ©Copyright Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI) Publisher Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI) BSIDC Colony, Off Boring-Patliputra Road Patna – 800 013 (BIHAR) Phone : 0612-2265649 Fax : 0612-2267102 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.adriindia.org Printer The Offsetters (India) Private Limited Chhajjubagh, Patna-800001 Study Sponsored by Pratichi (India) Trust Disclaimer This monograph may not reflect the views held either by the Centre for Economic Policy and Public Finance (CEPPF), ADRI or the Pratichi (India) Trust. Usual disclaimers apply. 2 Project Directors Prabhat P Ghosh Kumar Rana Field Team Sudeep Kumar Pandey Devendra Kumar Singh Shivnath Prasad Yadav Rakesh Kumar Shashi Ranjan Kumar Narendra Tripathi Bijendra Prasad Swarna Vijay Pandey Rahul Kumar Rakesh Kumar Shriniwas Onkar Ranjan Shashi Bhushan Mishra 3 CONTENTS Foreword i Acknowledgements ii List of Tables iii-iv List of Figures v Highlights vi-vii Chapter I Introduction 1-10 Socio-economic Profile of Bihar Sampling Design of Study Plan of the Report Chapter II Elementary Education in Bihar : An Overview 11-23 Literacy Rates in Bihar Elementary Education System Enrolment in Elementary Schools Incentive Schemes Chapter III Child Enrolment in Schools : Progress and Challenges 24-33 Enrolment Ratios Attendance Pattern Learning Achievement Chapter IV Parental Background : Social Segmentation in Education 34-44 Social Profile of Children Attitudinal Profile of Parents Learning Inputs at Home Private Expenditure in Education Chapter V Functioning -

Assessment of Land Governance in Bihar

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Assessment of Land Governance in Bihar Samanta, Debabrata and Jha, Jitendra Kumar and Dinda, Soumyananda Chandragupt Institute of Management Patna, Bihar, India, Deputy Director cum Joint Secretary (Retd.), Department of Revenue and Land Reforms, Government of Bihar, Sidho Kanho Birsha University, Purulia, India December 2013 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/64095/ MPRA Paper No. 64095, posted 02 May 2015 23:51 UTC Assessment of Land Governance in Bihar Debabrata Samanta Chandragupt Institute of Management Patna, Bihar; email: [email protected] Jitendra Kumar Jha, Deputy Director cum Joint Secretary (Retd.), Department of Revenue and Land Reforms, Government of Bihar and Soumyananda Dinda Chandragupt Institute of Management Patna, Chhajjubagh, Patna -800001. & S.K.B. University, Purulia, India. Email: [email protected] February, 2014 Abstract Land governance can be briefly described as how property rights to land, for groups or individuals, are defined, enforced, can be exchanged, and transformed. Land governance is argued to be a key to sustainable development and poverty reduction. In India, as well as in Bihar, land has enormous economic, social, and symbolic relevance. The present paper is an attempt to understand the issue of land governance from different perspective. The present study explores the historical background of development of land tenure typology and provides a detail account of land tenure system in the context of Bihar. As there are incidents of concentration in the ownership of the land and large number of disputes related to it, the paper analyse the available legal framework for dispute resolution. The present study also analyse some critical issues related to land governance and provide recommendation to bridge the gap for better land governance in the context of Bihar.