Season 2012-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

Keyboard Music

Prairie View A&M University HenryMusic Library 5/18/2011 KEYBOARD CD 21 The Women’s Philharmonic Angela Cheng, piano Gillian Benet, harp Jo Ann Falletta, conductor Ouverture (Fanny Mendelssohn) Piano Concerto in a minor, Op. 7 (Clara Schumann) Concertino for Harp and Orchestra (Germaine Tailleferre) D’un Soir Triste (Lili Boulanger) D’un Matin de Printemps (Boulanger) CD 23 Pictures for Piano and Percussion Duo Vivace Sonate für Marimba and Klavier (Peter Tanner) Sonatine für drei Pauken und Klavier (Alexander Tscherepnin) Duettino für Vibraphon und Klavier, Op. 82b (Berthold Hummel) The Flea Market—Twelve Little Musical Pictures for Percussion and Piano (Yvonne Desportes) Cross Corners (George Hamilton Green) The Whistler (Green) CD 25 Kaleidoscope—Music by African-American Women Helen Walker-Hill, piano Gregory Walker, violin Sonata (Irene Britton Smith) Three Pieces for Violin and Piano (Dorothy Rudd Moore) Prelude for Piano (Julia Perry) Spring Intermezzo (from Four Seasonal Sketches) (Betty Jackson King) Troubled Water (Margaret Bonds) Pulsations (Lettie Beckon Alston) Before I’d Be a Slave (Undine Smith Moore) Five Interludes (Rachel Eubanks) I. Moderato V. Larghetto Portraits in jazz (Valerie Capers) XII. Cool-Trane VII. Billie’s Song A Summer Day (Lena Johnson McLIn) Etude No. 2 (Regina Harris Baiocchi) Blues Dialogues (Dolores White) Negro Dance, Op. 25 No. 1 (Nora Douglas Holt) Fantasie Negre (Florence Price) CD 29 Riches and Rags Nancy Fierro, piano II Sonata for the Piano (Grazyna Bacewicz) Nocturne in B flat Major (Maria Agata Szymanowska) Nocturne in A flat Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 19 in C Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 8 in D Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia Or Online at Wrti.Org

Next on Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia or online at wrti.org. Encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series every Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. on WRTI-HD2 Saturday, November 1st, 2014, 5:00-6:00 p.m. The Taste of Bach Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). Concerto for Flute, Violin, Harpsichord in A minor, BWV 1044. Andrew Manze, violin (conductor), Rachel Brown, flute, Richard Egarr, harpsichord, Academy of Ancient Music. Harmonia Mundi 907283, Tr 7–9. 22:25 Bach. Concerto for Two Harpsichords and Strings in C, BWV 1061. Hank Knox, Luc Beauséjour, harpsichords, Arion, Jaap ter Linden. Early Music 7753, Tr 14–16. 16:46 Bach. Concerto for Four Harpsichords and Strings in A minor, BWV 1065. Raymond Leppard (conductor), An- drew Davies, Philip Ledger, Blandine Verlet, harpsichords, English Chamber Orchestra. Philips 4784614, Tr 13–15. 9:32 Let’s face it, the harpsichord is an acquired taste. In popular culture, never help- ful for appreciating the fine or unusual, the harpsichord is shorthand for—at best—stuffy, rich, out-of-touch, let-them-eat-cake. That’s at best. At worst, it’s sinister. And that doesn’t even count Lurch on The Addams Family. The harpsichord is a beautiful instrument that has often been misapplied. It has a delicate, refined sound, yet can help to keep the players onstage together. Indeed, before we stood conductors on their feet in front of everyone, they were often in the middle of the orches- tra, seated at and playing the harpsichord. -

Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Andante from Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major (J.S

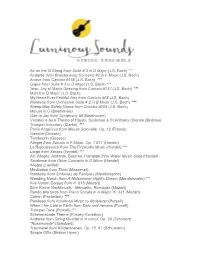

Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Andante from Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major (J.S. Bach) Arioso from Cantata #156 (J.S. Bach) *** Gigue from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring from Cantata #147 (J.S. Bach) *** March in D Major (J.S. Bach) My Heart Ever Faithful Aria from Cantata #68 (J.S. Bach) Rondeau from Orchestral Suite # 2 in B Minor (J.S. Bach) *** Sheep May Safely Graze from Cantata #208 (J.S. Bach) Minuet in G (Beethoven) Ode to Joy from Symphony #9 (Beethoven) Variations on a Theme of Haydn, Sicilienne & St Anthony Chorale (Brahms) Trumpet Voluntary (Clarke) *** Panis Angelicus from Messe Solonelle, Op. 12 (Franck) Gavotte (Gossec) Tambourin (Gossec) Allegro from Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 #11 (Handel) La Rejouissance from The Fireworks Music (Handel) *** Largo from Xerxes (Handel) *** Air, Allegro, Andante, Bourree, Hornpipe from Water Music Suite (Handel) Sarabane from Oboe Concerto in G Minor (Handel) Allegro (Loeillet) Meditation from Thais (Massenet) Rondeau from Sinfonies de Fanfares (Mendelssohn) Wedding March from A Midsummer Night's Dream (Mendelssohn) *** Ave Verum Corpus from K. 618 (Mozart) Eine Kleine Nachtmusik - Menuetto, Romanza (Mozart) Rondo alla turca from Piano Sonata in A Major, K. 331 (Mozart) Canon (Pachelbel) *** Rondeau from Incidental Music to Abdelazer (Purcell) When I Am Laid in Earth from Dido and Aeneas (Purcell) Trumpet Tune (Purcell) *** Scheherazade Theme (Rimsky-Korsakov) Andante from String Quartet in A minor, Op. 29 (Schubert) "Rosamunde" (Schubert) Traumerei from Kinderscenen, Op. 15, #7 (Schumann) Simple Gifts (Shaker Hymn) Presto from Sonatina in F Major (Telemann) Vivace from Sonata in F Major for flute (Telemann) Be Thou My Vision (Traditional Irish Melody) Danza Pastorale from Violin Concerto in E Major, Op. -

A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels Achareeya Fukiat Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Fukiat, Achareeya, "A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels" (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5630. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5630 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF SELECTED PIANO CONCERTI FOR ELEMENTARY, INTERMEDIATE, AND EARLY-ADVANCED LEVELS Achareeya Fukiat A Doctoral Research Project submitted to College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance James Miltenberger, -

Max Reger's Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Carole Terry, Chair Jonathan Bernard Craig Sheppard Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2019 Wyatt Smith ii University of Washington Abstract Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Carole Terry School of Music The history and performance of transcriptions of works by other composers is vast, largely stemming from the Romantic period and forward, though there are examples of such practices in earlier musical periods. In particular, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach found its way to prominence through composers’ pens during the Romantic era, often in the form of transcriptions for solo piano recitals. One major figure in this regard is the German Romantic composer and organist Max Reger. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Reger produced many adaptations of works by Bach, including organ works for solo piano and four-hand piano, and keyboard works for solo organ, of which there are fifteen primary adaptations for the organ. It is in these adaptations that Reger explored different ways in which to take these solo keyboard works and apply them idiomatically to the organ in varying degrees, ranging from simple transcriptions to heavily orchestrated arrangements. This dissertation will compare each of these adaptations to the original Bach work and analyze the changes made by Reger. It also seeks to fill a void in the literature on this subject, which often favors other areas of Reger’s transcription and arrangement output, primarily those for the piano. -

Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 Although the dating of Bach’s four orchestral suites is uncertain, the third was probably written in 1731. The score calls for two oboes, three trumpets, timpani, and harpsichord, with strings and basso continuo. Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Sympho ny Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite were given at the Auditorium Theatre on October 23 and 24, 1891, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15 , 16, 17, and 20, 2003, with Jaime Laredo conducting. The Orchestra first performed the Air and Gavotte from this suite at the Ravinia Festival on June 29, 1941, with Frederick Stock conducting; the complete suite was first performed at Ravinia on August 5 , 1948, with Pierre Monteux conducting, and most recently on August 28, 2000, with Vladimir Feltsman conducting. When the young Mendelssohn played the first movement of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite on the piano for Goethe, the poet said he could see “a p rocession of elegantly dressed people proceeding down a great staircase.” Bach’s music was nearly forgotten in 1830, and Goethe, never having heard this suite before, can be forgiven for wanting to attach a visual image to such stately and sweeping music. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers and when these four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks. -

9 Press Release ORCHESTRA of ST. LUKE's ANNOUNCES DETAILS of ITS SECOND BACH FESTIVAL, EXPLORING the MUSICAL OFFERING AND

Press Release ORCHESTRA OF ST. LUKE’S ANNOUNCES DETAILS OF ITS SECOND BACH FESTIVAL, EXPLORING THE MUSICAL OFFERING AND MUSIC OF HIS SONS JUNE 9-30, 2020 Featuring Performances at Carnegie Hall, The DiMenna Center for Classical Music, Manhattan School of Music’s Neidorff-Karpati Hall, and Temple Emanu-El’s Streicker Center OSL in Association with Carnegie Hall Presents Three Festival Programs in Zankel Hall, Led by Principal Conductor Bernard Labadie with Guest Artists Cellist Pieter Wispelwey, Harpsichordist Jean Rondeau, and Soprano Amanda Forsythe Festival Opens with Free Concert of Bach’s Cello Suites Performed by Pieter Wispelwey and Concludes with Four World Premieres Inspired by Bach’s The Musical Offering Masterclasses at The DiMenna Center for Classical Music with Pieter Wispelwey and Jean Rondeau with Students and Alumni from The Juilliard School Pianist Pedja Mužijević Performs Bach Family Album at The DiMenna Center for Classical Music New York, NY, January 14, 2020 — Orchestra of St. Luke’s (OSL) today announced detailed programming for the second annual OSL Bach Festival, spanning three weeks from June 9-30, 2020, with concerts and masterclasses across four venues in Manhattan—including three orchestral concerts at Carnegie Hall— and featuring guest artists cellist Pieter Wispelwey, harpsichordist Jean Rondeau, and soprano Amanda Forsythe. The OSL Bach Festival was launched last June to great success as part of the first season of esteemed Baroque and Classical Music specialist Bernard Labadie as OSL Principal Conductor. Highlights for the 2020 Festival include a performance of The Musical Offering, Bach’s masterpiece composition based on a theme by Frederick the Great, led and contextualized by Labadie. -

Bach, Johann Sebastian Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major

Bach, Johann Sebastian Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major Arioso from Cantata #156 Ave Maria adapted by Charles Gounod from WTC Prelude #1 Gigue from Suite # 3 in D Major Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring from Cantata #147 Sheep May Safely Graze from Cantata #208 Beethoven, Ludwig van Minuet in G Clarke, Jeremiah Trumpet Voluntary Gossec, Francois Joseph Gavotte Handel, George Frederick Allegro from Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 #11 Largo from Xerxes Sarabande from Suite # 4 in D minor for piano, 2nd set Water Music Suite Air Allegro Andante Bourree Finale Haydn, Franz Joseph Presto from String Quartet in F Major, Op. 74, #2 Ivanovici, J. Waltz from Waves of the Danube , #1 Massenet, Jules Elegie from Incidental Music to Les Erinnyes Mouret, Jean-Joseph Rondeau from Sinfonies de Fanfares Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus Eine Kleine Nachtmusik - String Quartet in G Major, K. 525 Allegro Menuetto Romanza Rondo Pachelbel, Johann Canon Schubert, Franz Adagio from Octet in F Major, Op. 166 Andante from String Quartet in A minor, Op. 29 "Rosamunde" Moment Musical from Op. 94, #3 Schumann, Robert Traumerei from Kinderscenen, Op. 15, #7 Telemann, George Philipp Presto from Sonatina in F Major Vivaldi, Antonio Concerto Grosso in D Minor, Op. 3, #11 Allegro Adagio Finale Wagner, Richard Bridal Chorus from Act III of Lohengrin Bach, Johann Sebastian Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major Allegro Andante Allegro assai Little Fugue March March in D Major from the Anna Magdalene Bach Notebook Rondeau from Orchestral Suite #2 in B Minor Beethoven, Ludwig van Ode to Joy from Symphony #9 Brahms, Johannes Hungarian Dance #5 Variations on a Theme of Haydn, Op.