Pond Farm Docent Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

"Große Berliner , Junge Und 'Alte in Den Galerien W Erner Scholz, Geor~E Gro&Z, Corpora, Emil Schumacher

11 "Große Berliner , Junge und 'Alte in den Galerien W erner Scholz, Geor~e Gro&z, Corpora, Emil Schumacher "Groß~' ist die ,.Berliner" vorläufig nur der ren und Uniformen, mit dem Hakenkreuz auf und daß diese ohne weiteres erkennbar wür• Zahl nach (ca. 1200 Werke), aber es kann dem Schlips und anderem Zierat, dann fragt den. Corpora ist trotz der Titel ·(Dunkler noch werden. Das Niveau der Münchner man sich. wieso diese Schießbudenfiguren Frühling. Schlaf. Halblaut) kein Lyriker, er müßte auch für Berlin erreichbar sein. wenn innerhalb eines demokratischen Staates das ist wie die meisten seiner Landsleute span man mehrGäste einlüde und gelegentlich eine 'Rennen gewinnen konnten. Die Frage, wie nungsreich und dramatisch, nur sehr indirekt, Sonderschau ausländischer Kollegen in Be weit Grosz heute noch aktuell ist, stellt sich und in seinen Mitteln gewählt. Er hat ein tracht zöge; es bliebe für die Berliner noch jeder Besucher der Ausstellung. wunderbares Nachtblau, das vielen seiner genug Platz in den großen Messehallen am Eine andere Frage ist, ob gegenwärtige Bilder (alle von 1957 bis 1958) einen Zug von Funkturm. Immerhin, was sich aus der wie Maler wie Corpora und Schumacher sich Heiterkeit nach überstandenen Katastrophen dergegründeten · "Juryfreien" unter Leitung außerhalb der Welt fühlen und art pur ve:c1eiht. des .. Berufsverbandes bildender Künstler machen oder ob in diesen Arbeiten genau so Für Schumacher ist die Farbe kein ästhe• Berlin" (Walter Wellenstein) entwickelt hat, viel Stellungnahme steckt wie bei Grosz. Nun, tisches Phänomen, eher ein konstruktives.. ist gut und notwendig, vielleicht weniger für Grosz war ein Einzelfall, neben ihm malten Seine Bilder sind oft hell wie eine sonnenooo~ die Kunst als für die nicht arrivierten Künst• Kandinsky und Klee, Max Ernst und Joan beschienene Felswand oder schwarz wie ein ler und dasPublikum, das immer noch glaubt, Miro6, und bei ihnen war in denselben zwan Bahrtuch oder rot wie eine Feuersbrunst. -

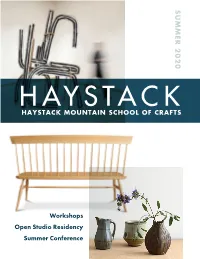

Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference

SUMMER 2020 HAYSTACK MOUNTAIN SCHOOL OF CRAFTS Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference Schedule at a Glance 4 SUMMER 2020 Life at Haystack 6 Open Studio Residency 8 Session One 10 Welcome Session Two This year will mark the 70th anniversary of the 14 Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. The decision to start a school is a radical idea in and Session Three 18 of itself, and is also an act of profound generosity, which hinges on the belief that there exists something Session Four 22 so important it needs to be shared with others. When Haystack was founded in 1950, it was truly an experiment in education and community, with no News & Updates 26 permanent faculty or full-time students, a school that awarded no certificates or degrees. And while the school has grown in ways that could never have been Session Five 28 imagined, the core of our work and the ideas we adhere to have stayed very much the same. Session Six 32 You will notice that our long-running summer conference will take a pause this season, but please know that it will return again in 2021. In lieu of a Summer Workshop 36 public conference, this time will be used to hold Information a symposium for the Haystack board and staff, focusing on equity and racial justice. We believe this is vital Summer Workshop work for us to be involved with and hope it can help 39 make us a more inclusive organization while Application broadening access to the field. As we have looked back to the founding years of the Fellowships 41 school, together we are writing the next chapter in & Scholarships Haystack’s history. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

California and the Fiber Art Revolution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Oakland Museum of California, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Baizerman, Suzanne, "California and the Fiber Art Revolution" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 449. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/449 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Imogene Gieling Curator of Crafts and Decorative Arts Oakland Museum of California Oakland, CA 510-238-3005 [email protected] In the 1960s and ‘70s, California artists participated in and influenced an international revolution in fiber art. The California Design (CD) exhibitions, a series held at the Pasadena Art Museum from 1955 to 1971 (and at another venue in 1976) captured the form and spirit of the transition from handwoven, designer textiles to two dimensional fiber art and sculpture.1 Initially, the California Design exhibits brought together manufactured and one-of-a kind hand-crafted objects, akin to the Good Design exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. -

Black Mountain Research

Black Mountain Research ein Buchprojekt von Annette Jael Lehmann unter Mitarbeit von Verena Kittel und Anna-Lena Werner / a book project by Annette Jael Lehmann with the assistance of Verena Kittel and Anna-Lena Werner introduction Annette Jael Lehmann and Anna-Lena Werner The practice-based research project Black they unite theoretical and curatorial endeavors tions outside North America. At the threshold of eventually successful and became a worldwide Mountain Research was a collaborative project into – well…what exactly? In other words: How art and pedagogy, liberal and pioneering in their architectural model only a few decades later. by Freie Universität Berlin and Hamburger could students, scholars, curators and artists curriculum, the educational institution revolu- Trial and error or even failure became at times Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin cooperate within one project? As a small team tionized models of academic teaching and lear- liberating forces at the college, opposing a pre- (2013-2015) that was developed along the muse- based at the Institute for Theater Studies at ning and fostered crucial strategies to contribute determined path towards knowledge, actions um exhibition ‘Black Mountain. An Interdiscip- Freie Universität Berlin – namely Verena Kittel, to a development that could now be described or results. The necessity of making mistakes, as linary Experiment 1933 – 1957’ (from 05.06. to Annette Jael Lehmann, and Anna-Lena Werner as practice-based research. Having an extensive Buckminster Fuller has prominently -

Peter Giopulos Files on Campus

Peter Giopulos Collection Artist Files Box A-B Folder # 1 – Art on Campus intro Folder # 2 – Art Walk Map Folder # 3 – Web Art Bill Stewart Folder # 4 – Art on Campus (A) Ansel Adams Samuel Marcus Adler George Gustave Adomeit Ahlgren, Roy B Charles Curtis Adams Frank Milton Armington Milton Clark Avery Folder # 5 – Josef Albers Folder # 6 – Mari Alexander Folder # 7 – Architecture on campus Folder # 8 – Harry Bertoia Folder # 9 – Art on campus (B) Otto Henry Bacher Federico Fiori Barocci Norman Arthur Bate Will Barnet Gustave Baumann Lester Beall Frank Weston Benson Thomas Hart Benton Alistair Bevington Sander Blondeel Milton Bond Walter H Cassebeer Borglum, Gutzon Philip Bornarth Charlotte Bowman Folder # 10 – Donald Bujnowski Doors Folder # 11 – Photo printed from collection Bujnowski 11 copies of 8x11 photographs of his work Box C-F Folder # 1 – Art on Campus C Robert Carter Walter H Cassebeer Wendell Castle John Channell Philip Cheney Ohi Chozaemon Carl Chiarenza John Scott Clubb Eugene C. Colby Robert Conge, Lila Copeland John Edwards Costigan James Crable Frank Craig Byron G Culver Folder # 2 – Augustus Wall Callcott Folder # 3 – Hans Christensen Folder # 4 – Art on campus [D-F] Henry Golden Dearth Henry De Maine Jose De Rivera David Dickinson Mitsui Eiichi Alejandro Fernandez Robert Fergerson Richard Aberle Florsheim Emil Fuchs Folder # 5 – Eisenhower dresses & Paintings in stage – Physical plant Folder # 6 – Harold (Hal) Foster Folder # 7 – Donald J Forsythe Box G-L Folder # 1 – Dan Kiley Folder # 2 – Art on Campus (G-H) Emil Ganso Moton Garchik Charles Dana Gibson Arthur Eric Rowton Gill Janet Goldner Nancy Gong Marion Greenwood Emile Albert Gruppe, Folder # 3 – Gordon Grant Folder # 4 – Gordon, Stanley Folder # 5 – Art on Campus (H) Silvanus G. -

The Bauhaus 1 / 70

GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 1 / 70 The Bauhaus 1 Art and Technology, A New Unity 3 2 The Bauhaus Workshops 13 3 Origins 26 4 Weimar 45 5 Dessau 57 6 Berlin 68 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 2 / 70 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT 3 / 70 1919–1933 Art and Technology, A New Unity A German design school where ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. © Kevin Woodland, 2020 Joost Schmidt, Exhibition Poster, 1923 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 4 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Twentieth-century furniture, architecture, product design, and graphics were shaped by the work of its faculty and students, and a modern design aesthetic emerged. MEGGS © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 5 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. MEGGS • The Arts & Crafts: Applied arts, craftsmanship, workshops, apprenticeship • Art Nouveau: Removal of ornament, application of form • Futurism: Typographic freedom • Dadaism: Wit, spontaneity, theoretical exploration • Constructivism: Design for the greater good • De Stijl: Reduction, simplification, refinement © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 6 / 70 1919–1933 -

B Au H Au S Im a G Inis Ta a U S S Te Llung S Füh Re R Bauhaus Imaginista

bauhaus imaginista bauhaus imaginista Ausstellungsführer Corresponding S. 13 With C4 C1 C2 A D1 B5 B4 B2 112 C3 D3 B4 119 D4 D2 B1 B3 B D5 A C Walter Gropius, Das Bauhaus (1919–1933) Bauhaus-Manifest, 1919 S. 24 S. 16 D B Kala Bhavan Shin Kenchiku Kōgei Gakuin S. 29 (Schule für neue Architektur und Gestaltung), Tokio, 1932–1939 S. 19 Learning S. 35 From M3 N M2 A N M3 B1 B2 M2 M1 E2 E3 L C E1 D1 C1 K2 K K L1 D3 F C2 D4 K5 K1 G D1 K5 G D2 D2 K3 G1 K4 G1 D5 I K5 H J G1 D6 A H Paul Klee, Maria Martinez: Keramik Teppich, 1927 S. 57 S. 38 I B Navajo Film Themselves Das Bauhaus und S. 58 die Vormoderne S. 41 J Paulo Tavares, Des-Habitat / C Revista Habitat (1950–1954) Anni und Josef Albers S. 59 in Amerika S. 43 K Lina Bo Bardi D und die Pädagogik Fiber Art S. 60 S. 45 L E Ivan Serpa und Grupo Frente Von Moskau nach Mexico City: S. 65 Lena Bergner und Hannes Meyer M S. 50 Decolonize Culture: Die École des Beaux-Arts F in Casablanca Reading S. 66 Sibyl Moholy-Nagy S. 53 N Kader Attia G The Body’s Legacies: Marguerite Wildenhain The Objects und die Pond Farm S. 54 Colonial Melancholia S. 70 Moving S. 71 Away H G H F1 I B J C F A E D2 D1 D4 D3 D3 A F Marcel Breuer, Alice Creischer, ein bauhaus-film. -

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity the Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity The Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Upholstery, drapery, and wall-covering samples 1923-29 Wool, rayon, cotton, linen, raffia, cellophane, and chenille Between 8 1/8 x 3 1/2" (20.6 x 8.9 cm) and 4 3/8 x 16" (11.1 x 40.6 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designer or Gift of Josef Albers ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Silk, cotton, and acetate 57 1/8 x 36 1/4" (145 x 92 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Wool and silk 7' 8 7.8" x 37 3.4" (236 x 96 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1926 Silk (three-ply weave) 70 3/8 x 46 3/8" (178.8 x 117.8 cm) Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Association Fund Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity - Exhibition Checklist 10/27/2009 Page 1 of 80 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Tablecloth Fabric Sample 1930 Mercerized cotton 23 3/8 x 28 1/2" (59.3 x 72.4 cm) Manufacturer: Deutsche Werkstaetten GmbH, Hellerau, Germany The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase Fund JOSEF ALBERS German, 1888-1976; at Bauhaus 1920–33 Gitterbild I (Grid Picture I; also known as Scherbe ins Gitterbild [Glass fragments in grid picture]) c. -

Nande 1974 Dec9 Complete.Pdf (5.406Mb)

\ 1 <;.--\· 11 ·h.(,u 'l=>v� ' ( ..-�T, a Rochester Institute of Technology -!.Y,, ' '.IJ(:I.-·, Published by l[Cffl Communications Services December 9-15, 1974 Police Veteran:" Just Realizing Need For Professionals" For 26 years, she worked the sure children weren't victims of department's Youth Aid Bureau, Incarceration. streets, the bars, and the violent crimes. which she commanded until she When she left the force, she hangouts in the city of The lady was a cop. retired in 1974. had just been promoted to Schenectady. Patricia M. Carter was She retired to join the faculty captain. For 26 years she helped Schenectady's first female pol ice of RIT's School of Criminal "But being an administrator I neglected children, found and officer in 1948. She worked as a Justice, where she is now an found I was supervising other counseled delinquent children, police youth officer, eventually instructor teaching Criminology people's work," she recalled. "I and worked with others to make founding, in 1966, the and the Alternatives to wasn't in contact with the people anymore." She determined she could "be contributing more" by teaching. She is soft-spoken, and almost petite. She is her own best example of what she calls the "change in caliber" of the police and others in the criminal justice system. The criminal justice system - from the police on the street to the courts and the penal institution--is undergoing a substantial change, she believes. "It's really a new field ... we're just beginning to realize the need for trained professionals in pol ice positions . -

Marguerite Wildenhain: Bauhaus to Pond Farm January 20 – April 15, 2007

MUSEUM & SCHOOLS PROGRAM EDUCATOR GUIDE Kindergarten-Grade 12 Marguerite Wildenhain: Bauhaus to Pond Farm January 20 – April 15, 2007 Museum & Schools program sponsored in part by: Daphne Smith Community Foundation of Sonoma County and FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE EXHIBITION OR EDUCATION PROGRAMS PLEASE CONTACT: Maureen Cecil, Education & Visitor Services Coordinator: 707-579-1500 x 8 or [email protected] Hours: Open Wednesday through Sunday 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Admission: $5 General Admission $2 Students, Seniors, Disabled Free for children 12 & under Free for Museum members The Museum offers free tours to school groups. Please call for more information. SONOMA COUNTY MUSEUM 425 Seventh Street, Santa Rosa CA 95401 T. 707-579-1500 F. 707-579-4849 www.sonomacountymuseum.org INTRODUCTION Marguerite Wildenhain (1896-1985) was a Bauhaus trained Master Potter. Born in Lyon, France her family moved first to Germany then to England and later at the “onset of WWI” back to Germany. There Wildenhain first encountered the Bauhaus – a school of art and design that strove to bring the elevated title of artist back to its origin in craft – holding to the idea that a good artist was also a good craftsperson and vice versa. Most modern and contemporary design can be traced back to the Bauhaus, which exalted sleekness and functionality along with the ability to mass produce objects. Edith Heath was a potter and gifted form giver who started Heath Ceramics in 1946 where it continues today in its original factory in Sausalito, California. She is considered an influential mid-century American potter whose pottery is one of the few remaining.